Phd-Thesis-Zubair-Shafiq.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movies Thatpack a Punch

Movies thatPack a 21 June JulyPunch - 01 2019 www.birminghamindianfilmfestival.co.uk Artist Cary Burman. Photo by Chila Rajinder Sawhney Kumari Celebrating our 5th Birthday, Birmingham Indian Film Festival which is part of the UK and Europe’s largest South Asian film festival is literally stuffed to the rafters with a rich assortment of entertaining and thought provoking independent films. This year’s highlights include Our Film, Power & Politics strand offers a red carpet opening night at a critical insight into the fast moving Cineworld Broad Street with the political changes of South Asia. The exciting premiere of cop whodunit astonishing documentary Reason by Article 15, starring Bollywood star Anand Patwardhan, Bangla suspense READYTO LAUNCH YOUR CAREER Ayushmann Khurrana and directed Saturday Afternoon and Gandhian by Anubhav Sinha. Our closing night black comedy #Gadhvi are a few films IN THE FILM INDUSTRY marks the return of Ritesh Batra, the to look out for. director of The Lunchbox with the premiere of Photograph starring the We are expecting a host of special MA Feature Film Development and legendary Nawazuddin Siddiqui and guests, including India’s most famous Sanya Malhotra. indie director Anurag Kashyap of MA Film Distribution and Marketing Sacred Games fame. Make sure you buy Our themes this year include the Young your tickets in advance for this one! Now open for applications Rebel strand which literally knocks out www.bcu.ac.uk/nti/courses all the stereotypes with a fist of movies We are delighted to welcome back our exploring younger lives. See director regular partners including Birmingham Rima Das’ award-winning teenage hit City University and welcome our new Bulbul Can Sing. -

19012004 Dt Mpr 06 D L C

DLD‹‰‰†‰KDLD‹‰‰†‰DLD‹‰‰†‰MDLD‹‰‰†‰C 6 MATINEE MASALA DELHI TIMES, THE TIMES OF INDIA MONDAY 19 JANUARY 2004 here was a time when Saif Ali Khan actually bid his colleagues goodbye, since he had no new films T on hand. Today the actor is back with a vengeance. UNUSUAL SUSPECTS With hits like Dil Chahta Hai, Darna Mana Hai and Kal he calmness of Gracy Singh’s someone is out to kill her. And every- Ho Na Ho to his credit, the Khan is not only looking good, white silk nightgown contrasts one around her seems like a suspect! but could be in line for some awards, keeping in mind his T sharply with her words. Gracy When Gautamji narrated the script to performances. But the actor has his head set firmly on admonishes Arbaaz Khan even as me I was very excited because he is his shoulders, and is willing to wait for the audiences ver- Sudesh Berry listens with unwaver- known for his thrillers on television.” dict. Friday will tell! is what he says. ing attention. “Cut,” director Gautam After Arbaaz’s polished portrayal in You have got two acclaimed performances in a row Adhikari’s voice booms through his debut Daraar and recent success with Darna Mana Hai and Kal Ho Na Ho. How does it White House at Khandala as Wajaah … with Qayamat, he will be spotted in a feel? A Reason To Kill inches a step forward. well-etched role in Wajaah… “I’m pla- It feels good to be a part of a film that is appreciated. -

P2m Percept Newsletter

/Issue 2/2006 e-newsletter of Table of Contents In the News 2 Awards & Accolades 3 Events & Happening 4 Up Close 5-6 1 IN THE NEWS Upen Patel in Percept Mr. Shailendra Singh awarded ''24 FPS Picture's action trilogy 2006 Power Personality of the Year” Percept Picture Company (PPC) is taking talent management to Recognising the best animation new arenas. Upen Patel will star in a Rs 25 crore yet-untitled talent in India, Maya Academy of project produced by Percept Picture Company. He will be doing Advanced Cinematics organised 3 action films for PPC. its 24 FPS Animation Awards at the Said Mr Shailendra Singh, "We have identified Upen as the future Ballroom in JW Marriott on Apr 21, action hero. He comes in with lots of style, panache and 2006. The show felicitated fresh attitude.” talent as well as professionals in the field of animation. Mr Shailendra Singh, Jt Managing Ramu’s English patience Director, Percept Holdings, and Experimental filmmaker, Ram Gopal Varma is making his first- the mastermind behind India's ever English film for Percept. blockbuster animation, 'Hanuman', was awarded '24 FPS A three-film deal has already been struck with Ram Gopal 2006 Power Personality of the Year'. Varma who was in Manhattan with Mr Shailendra Singh recently. The 24 FPS awards saw in attendance some of the best in the “We have fantastic scripts," said Mr Singh, "and our idea is to industry assembled at the Ballroom of JW Marriott. Some of take our Indian entertainment industry to the international the attendees included the likes of Ashish Kulkarni, Jai level." This would entail Indian directors using Indian ideas and Natrajan, Jesh Krishnamurthy, Joan Vogelesang, Kirneet international actors to create cinema for a global market. -

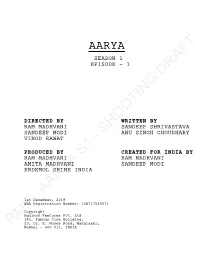

Aarya S1 Ep1.5 Shooting Draft 22Nd

AARYA SEASON 1 EPISODE - 1 DIRECTED BY WRITTEN BY RAM MADHVANI SANDEEP SHRIVASTAVA SANDEEP MODI ANU SINGH CHOUDHARY VINOD RAWAT PRODUCED BY CREATED FOR INDIA BY RAM MADHVANI RAM MADHVANI AMITA MADHVANI SANDEEP MODI ENDEMOL SHINE INDIA 1st December, 2019 SWA Registration Number: 108717539571 Copyright Equinox Features Pvt. Ltd 140, Famous Cine Building, 20, Dr. E. Moses Road, Mahalaxmi, RMFMumbai - - AARYA400 011, INDIA S1 - SHOOTING DRAFT FADE IN: 0A/0AA 0A/0AA TITLE SEQUENCE 1.1 EXT. POPPY FIELDS/ROAD. DAY. 1.1 **OMITTED** 1.2/2A INT. AARYA’S HOUSE. GYM/LIVING ROOM. DAY. 1.2/2ADRAFT We introduce a 40-year old, tall, fit and athletic woman, in her yoga pants upside down hanging on her training rings. A cleaning robot comes and cleans the area around her. Her phone is buzzing on vibrate. Her concentration is being challenged. There is the morning pandemonium. Outside we can hear clanking of utensils and squabble of two boys. VEER ADITYA Bag de. I want to check it Mere paas nahin hai, Bhaiya. myself. Mamma! She turns upside down and goes straight, takes a breath and dives deep into the routine crisis management of the home as she steps into the living room.SHOOTING She is AARYA. The house is modern and luxurious.- A maid, Poonam is overlooking packing the tiffins, a cook whips up the breakfast. She answers the call, it is from Soundarya. S1AARYA Hi Chotti. Aaj jaldi uthi hai yah kal raat bhar soyi nahin? SOUNDARYA (O.S) Didi, meri taang baad mein kheenchna. Hum pahle jeweler ko mil lein? Meanwhile,AARYA In the family den, Aarya’s two sons VEER (16) and ADITYA (8) are jostling in the living room. -

Dtp1june8final.Qxd

*DLTD80603/ /01/K/1*/01/Y/1*/01/M/1*/01/C/1* Geri’s in the Horror-scope: Bo goes Boom! She is only 5 feet, 3 inches tall. ng up and down in a bath tub, mood for Darna mana hai, But way back in 1979, Bo Der- it was Bo all the way! THE TIMES OF INDIA ek became every man’s fantasy For all those who still miss Sunday, June 8, 2003 baby talk! Saif tells Shilpa with her stunning 38-22-36 st- the perfect 10 bombshell, the ats. The daughter of a boat sa- lady’s back on the big screen in Page 7 Page 8 lesman, Bo was Kaizad Gust- the reigning sex ad’s Boom. And goddess of the not only does ‘80s, though she play herse- most of her fil- lf, Bo even recr- ms bombed. Be eates her famo- it Tarzan the us 10 scene. Apeman, whe- Guess who’s re you saw mo- gonna be runn- re of the sexy ing towards her Jane than the as she emerges lord of the jun- from the ocean, gle, A Change clad in a golden of Seasons, wh- saree? None ot- ich opened with her than apna OF INDIA footage of the Big B. Some gu- well-endowed ys have all the THANK GOD IT’S SUNDAY beauty bounci- luck! Wotsay? Photos: SATISH JAISWAL PRASHANT NAKWE DAVID ABRAHAM: DESIGNS ON DESTINY My mother died when I was places on my retur n to India. barely eight: My f ather,M athai SUNDAY SPECIAL Intershoppe was one of them. -

Catalogue 2011

Equipo Cines del Sur Director José Sánchez-Montes I Relaciones institucionales Enrique Moratalla I Director de programación Casimiro Torreiro I Asesores de programación Esteve Riambau, Gloria Fernández I Programador cinesdelsur. ext y Extraño Tanto Mar José Luis Chacón I Gerencia Elisabet Rus I Coordinadora de programación, comunicación, difusión Índice y prensa María Vázquez Medina I Departamento de Comunicación Ramón Antequera Rodríguez-Rabadán I Coordinadora de invitados Marichu Sanz de Galdeano I Coordinador Producción Enrique Novi I Departamento Producción Christian Morales, Juan Manuel Ríos I Jefa de prensa Nuria Díaz I Prensa Nuria García Frutos, Neus Molina I Publicaciones Carlos Martín I Catálogo y revista Laura Montero Plata I Gestión de tráfico de copias Reyes Revilla I Protocolo María José Gómez, Manuel 6 Presentación_Welcome Dominguez I Documentación Audiovisual Festival Jorge Rodríguez Puche, Rafael Moya Cuadros I Coordinador de traducción e interpretación Pedro Jesús Castillo I Traducción Pedro Jesús Castillo, Alexia Weninger, Hiroko Inose, Jesús de Manuel Jerez 11 Jurado_Jury I Secretario Jurado Oficial Toni Anguiano I Imagen del cartel Ángel Lozano I Diseño del premio Luis Jarillo I Cabecera LZ Producciones I +Factor Humano Antonio José Millán I Voluntarios José Ángel Martínez I Jefe técnico de proyecciones José Antonio Caballero Soler I Equipo técnico de proyecciones José Antonio Caballero Martín, José Domingo Raya, 19 Programación_Programming José Antonio Caballero Solier I Diseño Catálogo: Ángel Lozano, Juan Gómez, -

A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2015 Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Shabazz, Sultana Aaliuah, "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3607 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Sultana Aaliuah Shabazz entitled "Active Critical Engagement (ACE): A Pedagogical Tool for the Application of Critical Discourse Analysis in the Interpretation of Film and Other Multimodal Discursive Practices." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Education. Barbara J. Thayer-Bacon, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Harry Dahms, Rebecca Klenk, Lois Presser Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Adavi Nitin Movie Free 47

1 / 4 Adavi Nitin Movie Free 47 4) Apart of Tollywood movies he also worked as an actor in Bollywood movie “Agyaat”, which was released in 2009 and was dubbed into Telugu as 'Adavi'.. Watch Now: telugu jilebi movie hotadia jahan provaw xxx karishimax dog clip to all and girl sex ... Sona Hot leaked clip - malayalam actress- watchfull from telugu movie sex clip ... 20 min 47 sec, 67.5K Views ... in alone | telugu movie lesbian videos | telugu na peru surya movie | adavi telugu nithin movie 2009 | telugu movie .... Aranyamlo Latest Telugu Full Length Movie | 2017 Movies, Subscribe ... 0:00 / 1:58:47 ... Click here to Watch Renigunta Full Movie: https://goo.gl/oY55PH 2017 ... Adavi Lo Last Bus Telugu Full Movie | 2020 Latest Telugu Full .... Adavi Movie Online Watch Adavi Full Length HD Movie Online on YuppFlix. Adavi Film Directed by Ramesh G Cast Vinoth Krishnan,Ammu Abhirami.. Priyanka Kothari is playing heroine in Ramgopal Varma\'s 'Agyaat' (Hindi) and \'Adavi\' ( Telugu) opposite to Nithin.. Chatrapathi- ఛత్రపతి Telugu Full Movie || Prabhas || Shriya Saran || Bhanupriya || TVNXT. (2:39:30 min) ... (2:36:47 min) views ... Daring Tiger Nitin (Aatadista) Full Hindi Dubbed Movie | Nitin movies hindi dubbed, Kajal Agarwal. (2:2:31 min) ... Adavi Ramudu | Telugu Full Movie | NTR, Jayaprada, Jayasudha. (2:32:8 .... Rani Mukerji starrer Mardaani to be tax free in MP Get your ... The stunning actress turns 47 today. ... 'I enjoyed making Adavi Kachina Vennela' ... Nitin Kakkar's National award-winning film releases in Indian theatres tomorrow, June 6.. Find Nitin Varma's contact information, age, background check, white pages, criminal records, photos, .. -

Interlingual and Intersemiotic Transfer of Indian Cinema in Hong Kong

Indian Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies | 45 Author(s): Andy Lung Jan CHAN Published by: Indian Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies (IJCLTS) Issue Number: Volume 2, Number 1, February, 2014 ISSN Number: 2321-8274 Issue Editor: Rindon Kundu Editor : Mrinmoy Pramanick & Md Intaj Ali Website Link: http://ijclts.wordpress.com/ Interlingual and Intersemiotic Transfer of Indian Cinema in Hong Kong Abstract The history of Indian immigration to Hong Kong can be traced to the 1840s, when Hong Kong became a colony of the British Empire. However, Hong Kong Chinese people‟s knowledge of the local Indian community is limited. The stereotyping of Indian culture in the Hong Kong movie Himalaya Singh shows that Indian people and culture are often distorted and negatively portrayed in the media, and the secluded Indian community in Hong Kong is marginalised and neglected in the mainstream media. In recent years, Indian cinema has gained popularity in Hong Kong, but this survey of the Chinese movie titles, trailer subtitles and other publicity materials of four Indian movies (Slumdog Millionaire; 3 Idiots; English, Vinglish; and The Lunchbox) show that the films have to be recast and transfigured during interlingual and intersemiotic transfers so that it can become more accessible to Hong Kong Chinese audiences. 1. Introduction The history of Indian immigration to Hong Kong can be traced to the 1840s, when Hong Kong became a colony of the British Empire. In the social and economic development during the early colonial days, Indian people played an important role. Some Indian families have lived in the territory for generations and consider Hong Kong their home. -

DEFINATION the Capacity and Willingness to Develop, Organize

DEFINATION The capacity and willingness to develop, organize and manage a business venture along with any of its risks in order to make a profit. The most obvious example of entrepreneurship is the starting of new businesses. In economics, entrepreneurship combined with land, labor, natural resources and capital can produce profit. Entrepreneurial spirit is characterized by innovation and risk-taking, and is an essential part of a nation's ability to succeed in an ever changing and increasingly competitive global marketplace. Differences Between Women and Men Entrepreneurs When men and women start companies, do they approach the process the same way? Are there key differences? And how do those differences affect the success of the business venture? As a woman in the start-up community, I am frequently asked about women entrepreneurs. A popular question is: How are they different from men? There have been many studies of entrepreneurs and start-ups, and I’ve read a number of them. Many of them seem to me to fall short, because the researchers, not being entrepreneurs themselves, lack an in-depth understanding of the entrepreneurial mind. The result is often a lot of statistics that fail to enlighten readers about entrepreneurial behavior and motivation. So what follows are my personal opinions. They are not based on formal research, but on my own observations and interactions with other women entrepreneurs. 1. Women tend to be natural multitaskers, which can be a great advantage in start-ups. While founders typically have one core skill, they also need to be involved in many different aspects of their business. -

View Annual Report

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 FORM 20-F ☐ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR 12(g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☑ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended March 31, 2018 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☐ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number 001-32945 EROS INTERNATIONAL PLC (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Not Applicable (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) Isle of Man (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 550 County Avenue Secaucus, New Jersey 07094 Tel: (201) 558 9001 (Address of principal executive offices) Oliver Webster First Names (Isle of Man) Limited First Names House Victoria Road Douglas, IM2 4DF Isle of Man Tel: (44) 1624 630 630 Email: [email protected] (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered A ordinary share, par value GBP 0.30 per share The New York Stock Exchange Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act. None (Title of Class) Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act None (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. -

Management Discussion & Analysis

18 Balaji Telefilms Limited Annual Report 2012-13 MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION & ANALYSIS INDUSTRY REVIEW INDIAN ECONOMY The global economy faced another challenging year in 2012 as it continued to recover slowly following the global financial crisis of 2008. Slow US economic recovery, European sovereign debt crisis, moderating growth in China and other emerging economies continued to hold back the global GDP growth rates. As per a World Bank report ‘Global Economic Prospects’ released in January 2013, global economic growth was subdued at 2.3% in 2012. It is expected to remain flat in 2013 followed by a gradual increase to 3.1% and 3.3% in 2014 and 2015, respectively. 19 In addition to the weak global also likely in the global economy digital production techniques. New scenario, the Indian economy faced in 2013, prospects for the Indian content distribution platforms such as several internal macro-economic economy look better and real GDP broadband and digital cinema, direct- challenges such as high fiscal growth is expected to be in the range to-home (DTH) and digital cable deficit, large current account deficit, of 6.1% to 6.7% in FY2013 - 14. broadcasting, sophisticated electronic significant rupee depreciation, high devices etc. have resulted in the inflation, high interest rates and INDIAN MEDIA & emergence of new business models consequent slowdown in core sectors and revenue streams in the industry. as well as corporate and infrastructure ENTERTAINMENT Further, an increasing penetration of investments. The Indian GDP thus INDUSTRY multiplexes and entry of domestic as grew at only 5% in FY2012-13, the The Indian M&E industry, one of the well as international corporate houses lowest in the last decade.