THE BUCHAREST UNIVERSITY of ECONOMIC STUDIES The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movies Thatpack a Punch

Movies thatPack a 21 June JulyPunch - 01 2019 www.birminghamindianfilmfestival.co.uk Artist Cary Burman. Photo by Chila Rajinder Sawhney Kumari Celebrating our 5th Birthday, Birmingham Indian Film Festival which is part of the UK and Europe’s largest South Asian film festival is literally stuffed to the rafters with a rich assortment of entertaining and thought provoking independent films. This year’s highlights include Our Film, Power & Politics strand offers a red carpet opening night at a critical insight into the fast moving Cineworld Broad Street with the political changes of South Asia. The exciting premiere of cop whodunit astonishing documentary Reason by Article 15, starring Bollywood star Anand Patwardhan, Bangla suspense READYTO LAUNCH YOUR CAREER Ayushmann Khurrana and directed Saturday Afternoon and Gandhian by Anubhav Sinha. Our closing night black comedy #Gadhvi are a few films IN THE FILM INDUSTRY marks the return of Ritesh Batra, the to look out for. director of The Lunchbox with the premiere of Photograph starring the We are expecting a host of special MA Feature Film Development and legendary Nawazuddin Siddiqui and guests, including India’s most famous Sanya Malhotra. indie director Anurag Kashyap of MA Film Distribution and Marketing Sacred Games fame. Make sure you buy Our themes this year include the Young your tickets in advance for this one! Now open for applications Rebel strand which literally knocks out www.bcu.ac.uk/nti/courses all the stereotypes with a fist of movies We are delighted to welcome back our exploring younger lives. See director regular partners including Birmingham Rima Das’ award-winning teenage hit City University and welcome our new Bulbul Can Sing. -

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

Yuva Movie English Subtitles Download Torrent

1 / 2 Yuva Movie English Subtitles Download Torrent Manorama Online Movie section provides all movie news in Malayalam language. The movie channel covers Hollywood, Bollywood, Kollywood, Tollywood and.. Yuva Movie English Subtitles Download Torrent DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/2RSUlf5. Yuva Movie English Subtitles Download Torrent ->>->>->> http://bit.ly/2RSUlf5. Hindi Movies 2016 Full Movie - Mumbai Mirror - Bollywood Action Movies - English Subtitles.. YUVA 3 (2019). NEW RELEASED Hindi Dubbed Movie | Movies .... ... dubbed movie free download torrent Yuva full movies in hd hindi movie download in torrent malarvadi arts club english subtitles download .... Yuva. Release: DVDRip; Number of CD's: 1; Frame (fps): 23,976. Language: Turkish. Year: 2004. Uploader: DamlaK. Report Bad Movie Subtitle: Thanks (0).. Yuva Ratna a Telugu super Romance movie, starring Nandamuri Taraka Ratna, Jivida Sharma , music composed by M.M.Keeravani & directed ... Jai Gangaajal movie torrent download hd 720p, full movie, kickass download . ... Movie Hindi Dubbed Download 720p Hd .. ... mla,bjp office,opposition,Yuva ... Into the Storm kickass with english subtitles, Into the Storm movie free download, .... Download Gemini Man 2019 YTS and YIFY torrent HD (720p, 1080p and bluray) 100% free. you . ... No Country for Old Men yify movies torrent magnet with No Country for Old Men ... 1, Italian, subtitle No Country For Old Men 2007 720p BrRip x264 YIFY, Bepatient. ... Yuva Serial Title Song Free Download.. Yuva. (10)IMDb 7.42h 40min2004NR. Youth leader Michael is shot by hit man Inba. Arjun, a ... Subtitles: English ... Yuva is a rebellious, young generation movie.. The Official Home of YIFY Movies Torrent Download - YTS is the best website to download English movies with subs. -

P2m Percept Newsletter

/Issue 2/2006 e-newsletter of Table of Contents In the News 2 Awards & Accolades 3 Events & Happening 4 Up Close 5-6 1 IN THE NEWS Upen Patel in Percept Mr. Shailendra Singh awarded ''24 FPS Picture's action trilogy 2006 Power Personality of the Year” Percept Picture Company (PPC) is taking talent management to Recognising the best animation new arenas. Upen Patel will star in a Rs 25 crore yet-untitled talent in India, Maya Academy of project produced by Percept Picture Company. He will be doing Advanced Cinematics organised 3 action films for PPC. its 24 FPS Animation Awards at the Said Mr Shailendra Singh, "We have identified Upen as the future Ballroom in JW Marriott on Apr 21, action hero. He comes in with lots of style, panache and 2006. The show felicitated fresh attitude.” talent as well as professionals in the field of animation. Mr Shailendra Singh, Jt Managing Ramu’s English patience Director, Percept Holdings, and Experimental filmmaker, Ram Gopal Varma is making his first- the mastermind behind India's ever English film for Percept. blockbuster animation, 'Hanuman', was awarded '24 FPS A three-film deal has already been struck with Ram Gopal 2006 Power Personality of the Year'. Varma who was in Manhattan with Mr Shailendra Singh recently. The 24 FPS awards saw in attendance some of the best in the “We have fantastic scripts," said Mr Singh, "and our idea is to industry assembled at the Ballroom of JW Marriott. Some of take our Indian entertainment industry to the international the attendees included the likes of Ashish Kulkarni, Jai level." This would entail Indian directors using Indian ideas and Natrajan, Jesh Krishnamurthy, Joan Vogelesang, Kirneet international actors to create cinema for a global market. -

Shah Rukh Khan from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia "SRK" Redirects Here

Shah Rukh Khan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "SRK" redirects here. For other uses, see SRK (disambiguation). Shah Rukh Khan Shah Rukh Khan in a white shirt is interacting with the media Khan at a media event for Kolkata Knight Riders in 2012 Born Shahrukh Khan 2 November 1965 (age 50)[1] New Delhi, India[2] Residence Mumbai, Maharashtra, India Occupation Actor, producer, television presenter Years active 1988present Religion Islam Spouse(s) Gauri Khan (m. 1991) Children 3 Signature ShahRukh Khan Sgnature transparent.png Shah Rukh Khan (born Shahrukh Khan, 2 November 1965), also known as SRK, is an I ndian film actor, producer and television personality. Referred to in the media as "Baadshah of Bollywood", "King of Bollywood" or "King Khan", he has appeared in more than 80 Bollywood films. Khan has been described by Steven Zeitchik of t he Los Angeles Times as "perhaps the world's biggest movie star".[3] Khan has a significant following in Asia and the Indian diaspora worldwide. He is one of th e richest actors in the world, with an estimated net worth of US$400600 million, and his work in Bollywood has earned him numerous accolades, including 14 Filmfa re Awards. Khan started his career with appearances in several television series in the lat e 1980s. He made his Bollywood debut in 1992 with Deewana. Early in his career, Khan was recognised for portraying villainous roles in the films Darr (1993), Ba azigar (1993) and Anjaam (1994). He then rose to prominence after starring in a series of romantic films, including Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Dil To P agal Hai (1997), Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998) and Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham.. -

BJP Pits Pragya Against Digvijay ADMK, BJP

Follow us on: facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2019-21 @TheDailyPioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 OPINION 8 WORLD 11 SPORT 15 Published From THE EASTER SUDAN'S BASHIR MOVED TO JUVENTUS CRASH OUT DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL BHUBANESWAR RANCHI RAIPUR CHANDIGARH QUESTION PRISON AS PROTESTERS RALLY OF CHAMPIONS LEAGUE DEHRADUN HYDERABAD VIJAYWADA Late City Vol. 155 Issue 104 LUCKNOW, THURSDAY APRIL 18, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable HORROR HAS POTENTIAL: EMRAAN} } 14 VIVACITY www.dailypioneer.com BJP pits Pragya against Digvijay ADMK, BJP Digvijay has been a bitter Bhopal battle critic of the Rashtriya stakes high Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS), the ideological guide of the BJP, set to catch and had allegedly linked it to the 2008 Mumbai terror attack nation’s eye carried out by Pakistani ter- in 2nd phase rorists. PNS n NEW DELHI The BJP also decided to sented by the AIADMK, fol- field KP Yadav from Guna, a PNS n NEW DELHI lowing recovery of huge etting the stage for an epic seat held by senior Congress amount of cash allegedly from Sbattle in Bhopal, the BJP on leader Jyotiraditya Scindia who he second phase of Lok an associate of a DMK leader. Wednesday fielded Sadhvi is contesting from there. The TSabha polls for 95 seats will The EC also announced Pragya Singh Thakur, facing BJP has named Raj Bahadur decide the fate of several stal- postponement of polling in trial in Malegaon blast case, in Singh and Ramakant Bhargav warts, including Union Tripura (East) Lok Sabha seat Lok Sabha elections, against as its nominees from Sagar and Ministers Jitendra Singh, Jual to the third phase on April 23, Congress heavyweight and for- Vidisha respectively. -

HM 06 FEBRUARY Page 10.Qxd (Page 1)

www.himalayanmail.com 10 JAMMU ☯ SATURDAY ☯ FEBRUARY 06, 2021 ENTERTAINMENT The Himalayan Mail Katrina looks marvelous in her recent Varun Dhawan joins Ranveer Singh & commercial video along with Amitabh, Nagarjuna! Katrina Kaif is shooting Rohit Shetty on the sets of Cirkus! for her next horror-comedy film Phone Bhoot alongside Ishaan Khatter and Sid- dhant Chaturvedi. Recently, the actress shared her shoot diaries on social media where she can be seen doing fun with her Phone Bhoot gang. Similar pictures were also shared by Siddhant Chaturvedi. On Friday, Katrina Kaif reposted a video by Amitabh Bachchan on Instagram and captioned it, "Trust - the only emotion that binds every relationship. #TrustI- sEverything #BharosaHiS- abKuchHai." In the shared commercial advertisement, Amitabh Bachchan was seen alongside his wife Jaya and daughter Shweta Bachchan. It also stars Nagarjuna, Kat- rina Kaif, and Punjabi ac- tress Wamiqa Gabbi. Check out the video post here - On the work front, Katrina will share the screen space with Ishaan Khatter and Siddhant Chaturvedi in the horror-comedy film 'Phone Bhoot', helmed by Gurmeet Ranveer Singh is shooting for his comedy flick Cirkus and has been enjoying his time while shooting with Singh and produced by his favorite director Rohit Shetty. On Varun Sharma's birthday, Ranveer's co-star in the film, celebrated Ritesh Sidhwani and Farhan his birthday on the film sets and was accompanied by the newly married Varun Dhawan. Akhtar. She is also waiting Ranveer Singh shared a picture from the sets of Cirkus on Instagram featuring Varun Dhawan, Rohit for her next release Rohit Shetty, Jacqueline Fernandez, Pooja Hegde, and himself. -

REFERENCES Bharucha Nilufer E. ,2014. 'Global and Diaspora

REFERENCES Bharucha Nilufer E. ,2014. ‘Global and Diaspora Consciousness in Indian Cinema: Imaging and Re-Imaging India’. In Nilufer E. Bharucha, Indian Diasporic Literature and Cinema, Centre for Advanced Studies in India, Bhuj, pp. 43-55. Chakravarty Sumita S. 1998. National Identity in Indian Popular Cinema: 1947-1987. Texas University Press, Austin. Dwyer Rachel. 2002. Yash Chopra. British Film Institute, London. ___________. 2005. 100 Bollywood Films. British Film Institute, London. Ghelawat Ajay, 2010. Reframing Bollywood, Theories of Popular Hindi Cinema. Sage Publications, Delhi. Kabir Nasreen Munni. 1996. Guru Dutt, a Life in Cinema. Oxford University Press, Delhi. _________________. 1999/2005. Talking Films/Talking Songs with Javed Akhtar, Oxford University Press, Delhi. Kaur Raminder and Ajay J. Sinha (Eds.), 2009. Bollywood: Popular Indian Cinema through a Transnational Lens, Sage Publications, New Delhi. Miles Alice, 2009. ‘Shocked by Slumdog’s Poverty Porn’. The Times, London 14 January 2009 Mishra Vijay, 2002. Bollywood Cinema, Temples of Desire. Psychology Press, Rajyadhaksha Ashish and Willeman Paul (Eds.), 1999 (Revised 2003). The Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema. Routledge, U.K. Schaefer David J. and Kavita Karan (Eds.), 2013. The Global Power of Popular Hindi Cinema. Routledge, U.K. Sinha Nihaarika, 2014. ‘Yeh Jo Des Hain Tera, Swadesh Hain Tera: The Pull of the Homeland in the Music of Bollywood Films on the Indian Diaspora’. In Sridhar Rajeswaran and Klaus Stierstorfer (Eds.), Constructions of Home in Philosophy, Theory, Literature and Cinema, Centre for Advanced Studies in India, Bhuj, pp. 265- 272. Virdi Jyotika, 2004. The Cinematic ImagiNation: Indian Popular Films as Social History. Rutgers University Press, New Jersey. -

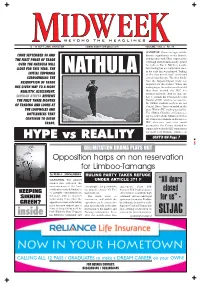

Midweek: Beyond the Headlines

13 - 19 Sept, 2006 111 13 - 19 SEPT, 2006, GANGTOK [email protected] VOLUME 1 NO. 2. Rs. 10 GANGTOK: Given the hype and the COME SEPTEMBER 30 AND historic significance of the historic THE FIRST PHASE OF TRADE trading links with Tibet, expectations were high when Nathula finally opened OVER THE NATHULA WILL for trade on June 6. But three months CLOSE FOR THIS YEAR. THE later trading has not really taken place NATHULA in the scale that was planned. Trading INITIAL EUPHORIA in the first month itself witnessed SURROUNDING THE several impediments. The first hurdle was the Import-Export Code for RESUMPTION OF TRADE required for the traders. When the HAS GIVEN WAY TO A MORE trading began, the traders were then told REALISTIC ASSESSMENT. that they needed the IEC for international trade. And for that, one SARIKAH ATREYA REVIEWS had to furnish his Personal Account THE FIRST THREE MONTHS Number (PAN), which is not issued to the Sikkim residents as there are not OF TRADING AND LOOKS AT Central Direct Taxes extended in the THE LOOPHOLES AND State. With no IEC, trading was stalled. BOTTLENECKS THAT The Sikkim Chamber of Commerce approached both the Sikkim as well as CONTINUE TO DETER Photo: PEMA L. SHANGDERPA the Central Government on the issue of TRADE. IEC clearance and after much persuasion, the Centre decided to temporarily waive the IEC requirement for trade over Nathula, which took CONT’D ON Page 7 HYPE vs REALITY K Y M C DELIMITATION DRAMA PLAYS OUT Opposition harps on non reservation for Limboo-Tamangs by PEMA L. -

Raazi V10 22-7-17 Clean

DHARMA PRODUCTIONS JUNGLEE PICTURES DIRECTED BY MEGHNA GULZAR SCREENPLAY BHAVANI IYER & MEGHNA GULZAR DIALOGUE MEGHNA GULZAR BASED ON THE NOVEL “CALLING SEHMAT” BY HARINDER S SIKKA © Meghna Gulzar 2017 FADE IN: 1 INT. PAK ARMY HQ - SITUATION ROOM - EVENING Title Card: February 1971. Pakistan. A series of pictures, black-and-white, low exposure but clearly outlining two figures and faces that are in deep conversation are seen on an old fashioned projector screen. Uniformed top brass from all the defense services (Army, Navy and Air Force) and Pakistan’s Intelligence sit around a table, being briefed by BRIGADIER SYED (57), tall hard-eyed with a striking military bearing in his uniform. The meeting is already in session. Syed clicks a button to zoom in on one of the men in the projected photograph. SYED Bangaal mein aazaadi ki tehreek zor pakad rahi hai. Vahaan Awami League ki khufiya Military Council ke rehnuma ye shakhs hain – Colonel Usmani. Lt. GENERAL AMIR BEIG (68), grey-haired with cold eyes looks at the image. BEIG Election bhi jeet chuke hain. Inki neeyat kya hai? The other senior leaders at the table murmur similarly. SYED Mujibur Rahman ne apne saath kuchh aise log jama kar liye hain, jo ab apne-aap ko Mukti fauj kehlate hain... (looks around) Mukti - aazaadi.. Sniggers around the room. Syed clicks for the picture to zoom in to the other face, only partially seen. SYED (CONT’D) Aur ye shakhs hai Khalid Mir... Iski padtaal rakhna bahaut zaroori hai. Ye Hindustan ke Intelligence ke bade afsar hain... Murmurs around the room. -

Interlingual and Intersemiotic Transfer of Indian Cinema in Hong Kong

Indian Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies | 45 Author(s): Andy Lung Jan CHAN Published by: Indian Journal of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies (IJCLTS) Issue Number: Volume 2, Number 1, February, 2014 ISSN Number: 2321-8274 Issue Editor: Rindon Kundu Editor : Mrinmoy Pramanick & Md Intaj Ali Website Link: http://ijclts.wordpress.com/ Interlingual and Intersemiotic Transfer of Indian Cinema in Hong Kong Abstract The history of Indian immigration to Hong Kong can be traced to the 1840s, when Hong Kong became a colony of the British Empire. However, Hong Kong Chinese people‟s knowledge of the local Indian community is limited. The stereotyping of Indian culture in the Hong Kong movie Himalaya Singh shows that Indian people and culture are often distorted and negatively portrayed in the media, and the secluded Indian community in Hong Kong is marginalised and neglected in the mainstream media. In recent years, Indian cinema has gained popularity in Hong Kong, but this survey of the Chinese movie titles, trailer subtitles and other publicity materials of four Indian movies (Slumdog Millionaire; 3 Idiots; English, Vinglish; and The Lunchbox) show that the films have to be recast and transfigured during interlingual and intersemiotic transfers so that it can become more accessible to Hong Kong Chinese audiences. 1. Introduction The history of Indian immigration to Hong Kong can be traced to the 1840s, when Hong Kong became a colony of the British Empire. In the social and economic development during the early colonial days, Indian people played an important role. Some Indian families have lived in the territory for generations and consider Hong Kong their home. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat.