Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grappling with the Bomb: Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

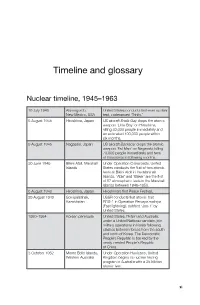

Timeline and glossary Nuclear timeline, 1945–1963 16 July 1945 Alamogordo, United States conducts first-ever nuclear New Mexico, USA test, codenamed ‘Trinity .’ 6 August 1945 Hiroshima, Japan US aircraft Enola Gay drops the atomic weapon ‘Little Boy’ on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people immediately and an estimated 100,000 people within six months . 9 August 1945 Nagasaki, Japan US aircraft Bockscar drops the atomic weapon ‘Fat Man’ on Nagasaki, killing 70,000 people immediately and tens of thousands in following months . 30 June 1946 Bikini Atoll, Marshall Under Operation Crossroads, United Islands States conducts the first of two atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. ‘Able’ and ‘Baker’ are the first of 67 atmospheric tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946–1958 . 6 August 1948 Hiroshima, Japan Hiroshima’s first Peace Festival. 29 August 1949 Semipalatinsk, USSR conducts first atomic test Kazakhstan RDS-1 in Operation Pervaya molniya (Fast lightning), dubbed ‘Joe-1’ by United States . 1950–1954 Korean peninsula United States, Britain and Australia, under a United Nations mandate, join military operations in Korea following clashes between forces from the south and north of Korea. The Democratic People’s Republic is backed by the newly created People’s Republic of China . 3 October 1952 Monte Bello Islands, Under Operation Hurricane, United Western Australia Kingdom begins its nuclear testing program in Australia with a 25 kiloton atomic test . xi GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB 1 November 1952 Bikini Atoll, Marshall United States conducts its first Islands hydrogen bomb test, codenamed ‘Mike’ (10 .4 megatons) as part of Operation Ivy . -

Information Regarding Radiation Reports Commissioned by Atomic Weapons

6';ZeKr' LOOSE MIN= C 31 E Tot' Task Force Commander, Operation Grapple 'X' A 0 \ Cloud Sampling 1. It is agreed that the meteorological conditions at Christmas Island, although ideal in sane ways, pose oonsiderable problems in others. First31„ the tropopause at Christmas Island varies between 55,000 and 59,000 ft; thin is in contrast to the tropopause in the U.S. Eniwetok area which is more usually around 45,000 ft. and, under conditions of small, i.e. under two megaton bursts, may give quite different cloud ooncentrations. In the Eniwetok area the mushroom tends to leave some cloud at tropopause and then go on up producing a small sample at tropopause level, but the main body being much higher does not cause the problem of "shine" that is caused at Christmas Island where the difference of 12,000 to 15,000 extra feet in tropopause level tends to result in the upward rise of the oloud immediately after this level being slower and the spread immediate thereby causing an embarrassing amount of "shine" to the cloud samplers who must be over 50,000 ft. The other thing which I think must be borne in mind is the temperature at the 60,000 ft. level in the Christmas Island area. If this is minus 90° or over, trouble may well be expected from "flame-out" in rocket assisted turbo-jet aircraft. It is frequently minus 82° at 53,000 ft. 2. We have tended to find in past trials that the area between the base of the cloud and the sea is, to all intents and purposes, free from significant radiation. -

60 Anniversary of Valiant's First Flight

17th May 2011 60th Anniversary of Valiant’s First Flight First Flight 18th May 1951 Wednesday 18th May 2011 will mark the 60th Anniversary of the first flight of the Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant. Part of the Royal Air Forces V-Bomber nuclear deterrent during the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to make it into the air, when prototype WB210 took to the skies on 18th May 1951. The Royal Air Force Museum Cosford is home to the world’s only complete example, Vickers-Armstrongs Valiant B (K).1 XD818. The Valiant is on display in the Museums award winning National Cold War Exhibition, the only place in the world where you can see all three of Britain’s V-Bombers: Vulcan, Victor and Valiant on display together under one roof. This British four jet bomber went into active RAF service in 1955 and played a significant role during the Cold War period. With a wingspan of 114ft, over 108ft in length and a height of over 32ft, the Valiant had a bomb capacity of a 10,000lb nuclear bomb or 21 x 1,000lb conventional bombs. In total 107 aircraft were built, each carrying a crew of five including two pilots, two navigators and an air electronics officer. The type was retired from RAF service in 1965 due to structural problems. RAF Museum Cosford Curator, Al McLean says: "The Valiant was the first of the V-bombers to enter service, the first to drop a nuclear weapon and the first to go into combat. -

Atlantic Flight from Friedrichshafen, Germany

February 2016 Issue 15 TAKE OFF! AIR15 ARB05 1930 Dornier Do X Flying Boat first Trans- Atlantic flight from Friedrichshafen, Germany - New York with both the red square and black cachets - the ARA101A Group Captain Kenneth Hubbard journey took 9 signed 1957 First Megaton Trial cover with BFPO months £200 Christmas Island CDS, he piloted the Valiant £50 a month for 4 months Bomber which dropped Britain’s first live H-Bomb on 15/05/57 during Operation Grapple £350 £70 a month for 5 months ARR31 1933 Great Western Railway Birmingham - Cardiff first flight £90 ARB55 4 Dutch ARB149 1946 BOAC London - Egypt Test Letter ‘Boesman’ No.9 with original BOAC test letter Memorandum, Balloon rare and interesting item this was flown before any flown cards each with great cachets - official first flights of the route£125 one has been signed by Nini Boesman £25 a month for 5 months and one by John Boesman £75 ARE225AS 1935 Blackpool & West Coast Air Services, Isle of Man - Liverpool first flight of the new contract, signed by the pilot Higgins £75 SGE032B Amelia Earhart signed 1929 cover with black first amphibian flight illustration and Detroit, Michigan postmark £1000 £100 a month for 10 months SGE032D Amelia Earhart signed 1929 cover with green first amphibian flight illustration and Cleveland, Ohio postmark £1200 £200 a month for 6 months Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] European Airmail ARE202 1934 Souvenir Pigeongram ARE217 1972 60th Anniversary -

Roy Dommett Interviewed by Dr Thomas Lean

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES AN ORAL HISTORY OF BRITISH SCIENCE Roy Dommett Interviewed by Dr Thomas Lean C1379/14 © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk IMPORTANT This interview and transcript is accessible via http://sounds.bl.uk . © The British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators. © The British Library Board http://sounds.bl.uk The British Library National Life Stories Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref no: C1379/14 Collection title: An Oral History Of British Science Interviewee’s Dommett Title: Mr surname: Interviewee’s Roy Sex: Male forename: Occupation: Rocket scientist, Date and place of birth: 25th June 1933 aeronautical engineer. Mother’s occupation: Father’s occupation: Painter and decorator Dates of recording, Compact flash cards used, tracks (from – to): March 18 (1-3), April 13 (4-5), April 20 (6-10), 20 July (11-14), 16 September (15-19) 2010 Location of interview: Interviewee’s home, Fleet. Name of interviewer: Thomas Lean Type of recorder: Marantz PMD661 on secure digital [tracks 1 - 10] and Marantz PMD660 on compact flash [tracks 11 - 19] Recording format : WAV 24 bit 48 kHz (tracks 1 - 10), WAV 16 bit 48 kHz (Tracks 11-19). -

Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

Introduction From the beginning of the nuclear age, the United States, Britain and France sought distant locations to conduct their Cold War programs of nuclear weapons testing. For 50 years between 1946 and 1996, the islands of the central and south Pacific and the deserts of Australia were used as a ‘nuclear playground’ to conduct more than 315 atmospheric and underground nuclear tests, at 10 different sites.1 These desert and ocean sites were chosen because they seemed to be vast, empty spaces. But they weren’t empty. The Western nuclear powers showed little concern for the health and wellbeing of nearby indigenous communities and the civilian and military personnel who staffed the test sites. In the late 1950s, nearly 14,000 British military personnel and scientific staff travelled to the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony (GEIC) in the central Pacific to support the United Kingdom’s hydrogen bomb testing program. In this military deployment, codenamed Operation Grapple, the British personnel were joined by hundreds of NZ sailors, Gilbertese labourers and Fijian troops.2 Many witnessed the nine atmospheric nuclear tests conducted at Malden Island and Christmas (Kiritimati) Island between May 1957 and September 1958. Today, these islands are part of the independent nation of Kiribati.3 1 Stewart Firth: Nuclear Playground (Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1987). 2 Between May 1956 and the end of testing in September 1958, 3,908 Royal Navy (RN) sailors, 4,032 British army soldiers and 5,490 Royal Air Force (RAF) aircrew were deployed to Christmas Island, together with 520 scientific and technical staff from the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE)—a total of 13,980 personnel. -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

Nuclear Weapons FAQ (NWFAQ) Organization Back to Main Index

Nuclear Weapons FAQ (NWFAQ) Organization Back to Main Index This is a complete listing of the decimally numbered headings of the Nuclear Weapons Frequently Asked Questions, which provides a comprehensive view of the organization and contents of the document. Index 1.0 Types of Nuclear Weapons 1.1 Terminology 1.2 U.S. Nuclear Test Names 1.3 Units of Measurement 1.4 Pure Fission Weapons 1.5 Combined Fission/Fusion Weapons 1.5.1 Boosted Fission Weapons 1.5.2 Staged Radiation Implosion Weapons 1.5.3 The Alarm Clock/Sloika (Layer Cake) Design 1.5.4 Neutron Bombs 1.6 Cobalt Bombs 2.0 Introduction to Nuclear Weapon Physics and Design 2.1 Fission Weapon Physics 2.1.1 The Nature Of The Fission Process 2.1.2 Criticality 2.1.3 Time Scale of the Fission Reaction 2.1.4 Basic Principles of Fission Weapon Design 2.1.4.1 Assembly Techniques - Achieving Supercriticality 2.1.4.1.1 Implosion Assembly 2.1.4.1.2 Gun Assembly 2.1.4.2 Initiating Fission 2.1.4.3 Preventing Disassembly and Increasing Efficiency 2.2 Fusion Weapon Physics 2.2.1 Candidate Fusion Reactions 2.2.2 Basic Principles of Fusion Weapon Design 2.2.2.1 Designs Using the Deuterium+Tritium Reaction 2.2.2.2 Designs Using Other Fuels 3.0 Matter, Energy, and Radiation Hydrodynamics 3.1 Thermodynamics and the Properties of Gases 3.1.1 Kinetic Theory of Gases 3.1.2 Heat, Entropy, and Adiabatic Compression 3.1.3 Thermodynamic Equilibrium and Equipartition 3.1.4 Relaxation 3.1.5 The Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution Law 3.1.6 Specific Heats and the Thermodynamic Exponent 3.1.7 Properties of Blackbody -

Ministry of Defence Acronyms and Abbreviations

Acronym Long Title 1ACC No. 1 Air Control Centre 1SL First Sea Lord 200D Second OOD 200W Second 00W 2C Second Customer 2C (CL) Second Customer (Core Leadership) 2C (PM) Second Customer (Pivotal Management) 2CMG Customer 2 Management Group 2IC Second in Command 2Lt Second Lieutenant 2nd PUS Second Permanent Under Secretary of State 2SL Second Sea Lord 2SL/CNH Second Sea Lord Commander in Chief Naval Home Command 3GL Third Generation Language 3IC Third in Command 3PL Third Party Logistics 3PN Third Party Nationals 4C Co‐operation Co‐ordination Communication Control 4GL Fourth Generation Language A&A Alteration & Addition A&A Approval and Authorisation A&AEW Avionics And Air Electronic Warfare A&E Assurance and Evaluations A&ER Ammunition and Explosives Regulations A&F Assessment and Feedback A&RP Activity & Resource Planning A&SD Arms and Service Director A/AS Advanced/Advanced Supplementary A/D conv Analogue/ Digital Conversion A/G Air‐to‐Ground A/G/A Air Ground Air A/R As Required A/S Anti‐Submarine A/S or AS Anti Submarine A/WST Avionic/Weapons, Systems Trainer A3*G Acquisition 3‐Star Group A3I Accelerated Architecture Acquisition Initiative A3P Advanced Avionics Architectures and Packaging AA Acceptance Authority AA Active Adjunct AA Administering Authority AA Administrative Assistant AA Air Adviser AA Air Attache AA Air‐to‐Air AA Alternative Assumption AA Anti‐Aircraft AA Application Administrator AA Area Administrator AA Australian Army AAA Anti‐Aircraft Artillery AAA Automatic Anti‐Aircraft AAAD Airborne Anti‐Armour Defence Acronym -

Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests by Nic Maclellan

LSE Review of Books: Book Review: Grappling with the Bomb: Britain’s Pacific H-Bomb Tests by Nic Maclellan Page 1 of 3 Book Review: Grappling with the Bomb: Britain’s Pacific H-Bomb Tests by Nic Maclellan In Grappling with the Bomb: Britain’s Pacific H-Bomb Tests, Nic Maclellan gathers together oral history and archival materials to bring forth a more democratic history of the British hydrogen bomb test series Operation Grapple, conducted in the South Pacific between 1957-58. Centralising the experiences and voices of Pacific islanders still affected by the detonations and still fighting for recognition and recompense from the UK government, this book — available to download here for free — offers a textured, multi-layered story that gives urgent attention to historical legacies of nuclear harm and injustice, writes Tom Vaughan. Grappling with the Bomb: Britain’s Pacific H-Bomb Tests. Nic Maclellan. ANU Press. 2017. Find this book: Sixty years after the British hydrogen bomb test series Operation Grapple was conducted in the South Pacific, its remaining survivors — now octogenarians — continue to fight for recognition and recompense from the UK government. The Grapple series, running from May 1957 to September 1958, consisted of nine nuclear detonations across test sites on Malden and Christmas (Kiritimati) Islands and announced the UK’s arrival as the world’s third thermonuclear power. As a shrinking Empire trickled through Britannia’s fingers, Grapple briefly salved the rapidly developing British condition of postcolonial melancholia by anointing the UK with destructive capabilities disproportionate to its diminishing influence, and helping to secure British ‘seats at the table’ in global affairs for decades to come. -

Defence Industrial Strategy Defence White Paper CM 6697

Defence Industrial Strategy Defence Values for Acquisition This statement of values is intended to shape the behaviour of all those involved in acquisition, including Ministers, Defence Management Board members, customers at all levels, the scrutiny community, project teams in the various delivery organisations and our private sector partners. Everything we do is driven by the Defence Vision: The Defence Vision Defending the United Kingdom and its interests Strengthening international peace and stability A FORCE FOR GOOD IN THE WORLD We achieve this aim by working together on our core task to produce battle-winning people and equipment that are: ¥ Fit for the challenge of today ¥ Ready for the tasks of tomorrow ¥ Capable of building for the future By working together across all the Lines of Development, we will deliver the right equipment and services fi t for the purpose required by the customer, at the right time and the right cost. In delivering this Vision in Acquisition, we all must: ¥ recognise that people are the key to our success; equip them with the right skills, experience and professional qualifi cations; ¥ recognise the best can be the enemy of the very good; distinguish between must have, desirable, and nice to have if aff ordable; ¥ identify trade off s between performance, time and cost; cases for additional resources must off er realistic alternative solutions; ¥ never assume additional resources will be available; cost growth on one project can only mean less for others and for the front line; ¥ understand that time matters; -

Britain's Pacific H-Bomb Tests

4 The Task Force Commander— Wilfred Oulton Grapple Task Force Commander Air Vice Marshall Wilfred Oulton Source: UK Government . 69 GRAPPLING WITH THE BOMB In February 1956, Air Vice Marshall Wilfred Oulton was appointed as Task Force Commander for Britain’s hydrogen bomb testing program. His commanding officer, Air Vice Marshall Lees, told him ‘to go out and drop a bomb somewhere in the Pacific and take a picture of it with a Brownie camera’.1 As they prepared for the operation, the British military were well aware of the environmental and political fallout of the Bravo test and US testing in the Marshall Islands. On the very day that he found out about his job, Oulton was told ‘we can’t have another incident like the American trouble at Bikini’ and presented with a bundle of documents to browse in preparation for the task: Extracts from American journals, notes on visits and so on, including reports on the US test in which Japanese fishermen were injured by fallout and on the wave of shrill criticism which ensued.2 For Oulton, who had joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1929 and gained rapid promotion during the Second World War, the timeline to prepare for Britain’s hydrogen bomb test was daunting. At the time of his appointment, he had no staff or offices and an uncertain budget. Within a year, however, he had to establish a military base and scientific facilities on an atoll thousands of kilometres away in the central Pacific. The Task Force chose the name ‘Grapple’ for the operation.