Serjeant Robinson, "Bench and Bar: Reminiscences of One of the Last Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F Non-Violent Mentallyill

Association ~ of Counties Washington, D.C. wwvy.countynews.org Vol. 34 No.12 ~ June17, 2002 Bush asks for new Cabinet Department of Homeland Security BY M. MINDYMORElTI Chemical, Biological, Radio- SEMOR STAFF IVRITER logical and Nuclear Countermea- In a recent primetime address sures, and to the nation, President George W. ~ Information Analysis and In- Bush proposed creating a new De- frastructure Protection. partment ofHomeland Security. If Another key component of the approved, this new department new department, and possibly the would be the first new major gov- one most vital to county govern- ernment department in more than ments, is the State/Local Govern- 50 years, and would pull together ment & Private Sector Coordina- several government entities already tion. Under this coordination, the in existence. The president's pro- department would streamline rela- posal closely mirrors a bi-partisan tions with the federal government Senate bill introduced in May. forstate and local The Photo by Donald Murray governments. As part of the president's pro- new department would contain an President-elect Ken Mayfield (r) discusses his testimony with Senate Judiciary Chairman Patrick posal, agencies such as the Federal intergovernmental hy (D-vt.). affairs officethat Emergency Management Agency would coordinate the federal home- (FEMA), the Coast Guard, Cus- land security programs with local toms Service, Boarder Patrol, Im- officials. ayfield calls for diversion migration and Naturalization Ser- It would give state and local vice (INS), the Animal and Plant officialsone primary contact instead HealthInspecuon Service(APHIS), of many, and there would be an f non-violent mentally ill the recently created Transportation additional primary contact just for Security Administration, the training, equipment, planning and Nuclear Emergency Search Team other critical needs emer- Bl Donacb MURRai such as a year as part ofa coalition of more Paula M. -

Life of Mary Wollstonecraft

l In vVr>. , {«'*' Vt.j UK ni^' V \* V> HHHBHnHSBBHc H HI IBQHU Class. Book COPYRIGHT DEPOSIT y » LIFE OF MARY WOLLSTONECRAFT. BY ELIZABETH ROBINS PENNELL. ^STON: ROBER . 3 BROTHERS. 1884. Copyright, 1884, By Roberts Brothers. iz- tfrVj University Press : John Wilson And Son, Cambridgi \y PREFACE. Comparatively little has been written about the life of Mary Wollstonecraft. The two authorities upon the subject are Godwin and Mr. C. Kegan Paul. In writing the following Biography I have relied chiefly upon the Memoir written by the former, and the Life of Godwin and Prefatory Memoir to the Letters to Imlay of the latter. I have endeavored to supplement the facts recorded in these books by a careful analysis of Mary Wollstonecraft's writings and study of the period in which she lived. I must here express my thanks to Mr. Gar- nett, of the British Museum, and to Mr. C. Kegan Paul, for the kind assistance they have given me in my work. To the first named of these gentlemen I am indebted for the loan of a manuscript containing some particulars of Mary Wollstonecraft's last illness which have never yet appeared in print, and to Mr. Paul for the gift, as well as the loan, of several impor- tant books. E. R. P. London, August, 1884. CONTENTS. Page Introduction i Chapter I. Childhood and Early Youth. 17 59-1778 . 12 II. First Years of Work. 1778-1785 .... 30 III. Life as Governess, i 786-1 788 ...... 60 IV. Literary Life. 1 788-1 791 85 V. Literary Work. -

Archaeological Papers Published

INDEX OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PAPERS PUBLISHED IN 1907 [BEING THE SEVENTEENTH ISSUE OF THE SERIES AND COMPLETING THE INDEX FOR THE PERIOD 1891-1907] COMPILED BY BERNARD GOMME PUBLISHED BY ARCHIBALD CONSTABLE & COMPANY LTD 10, ORANGE STREET, LEICESTER SQUARE, W.C. UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE CONGRESS OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETIES IN UNION WITH THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES 1908 CONTENTS [Those Transactions for the first time included in the index are marked with an asterisk,* the others are continuations from the indexes of 1891-190G. Transactions included for the first time are indexed from 1891 onwards.} Anthropological Institute, Journal, vol. xxxvii. Antiquaries, Ireland, Proceedings of Royal Society, vol. xxxvii. Antiquaries, London, Proceedings of Royal Society, 2nd S. vol. xxi. pt. 2. Antiquaries, Newcastle, Procceedings of Society, vol. x., 3rd S. vol. ii. Antiquaries, Scotland, Proceedings of Society, vol. xli. Archaoologia ^Eliana, 3rd S. vol. iii. Archssologia Cambrensis, 6th S. vol. vii. Archaeological Institute, Journal, vol. Ixiv. Berks, Bucks and Oxfordshire Archaeological Journal, vols. xii. (p. 97 to end), xiii. Biblical Archsoology, Society of, Proceedings, vol. xxix. Birmingham and Midland Institute, Transactions, vol. xxxii. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, Transactions, vols. xxix. pt. 2, xxx. pt. 1 (to p. 179). British Academy, Proceedings, 1905 and 1900. British Archieological Association, Journal, N.S. vol. xiii. British Architects, Royal Institute of, Journal, 3rd S. vol. xiv. British Numismatic Journal, 1st S. vol. iii. British School at Athens, Annual, vol. xii. British School at Rome, Papers, vol. iv. Buckinghamshire Architectural and Archaeological Society, Records, vol. ix. pt. 4 (to p. 324). Cambridge Antiquarian Society, Transactions, vol. -

Soho Action Plan: Your Thoughts in Action

Soho Action Plan: Your thoughts in action One Soho Soho is a unique part of the t it has an international identity as a cros ities and energy of the people who live an Without order we cannot live in, work in, o pleasant experience and we will work with ense of belonging and a wide range of op e of the most exciting and colourful part uraging diversity in retail and protecting up dialogue between businesses and re he foundations for enterprise in Soho. Re e look after the heart of this city. We propo neration, and we will improve the public re Contents 1 Introduction 3 Foreword 7 One Soho 13 Order 21 Opportunity 27 Enterprise 35 Renewal: Our lasting legacy 41 One Soho, One City, One Action Plan 45 List of actions 52 Contact details capital that has grown out of a rich s-cutting and cosmopolitan melting nd work here, which makes this area or visit Soho in enjoyment and peace. h the police and the Soho community pportunities in Soho that make even ts of the capital, if not the world, in Soho’s core businesses, promoting esidents, making the council more enewal: Our lasting legacy We will be ose real consultation with residents, ealm to make Soho accessible to all. Soho Boundary Soho is the area within the boundaries set by Oxford Street, Regent Street, Shaftesbury Avenue, and Charing Cross Road (for the purpose of this Action Plan). Featured Imagery 1 KINGLY COURT 2 SOHO HOTEL 3 SOHO SQUARE TOTTENHAM 4 MEARD STREET COURT ROAD 5 BERWICK STREET MARKET 6 GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET 19 20 18 GREA OXFORD STREET TCH W CH TON RO Additional Streets -

Season 2019 – 2020 Avalon Sailing Club Clareville Beach, Pittwater

! Season 2019 – 2020 Avalon Sailing Club Clareville Beach, Pittwater ! www.avalonsailingclub.com.au Award winning team Waterfront & oceanfront specialists James Baker and his team have been ranked again in the top 100 agents in Australia by both REB and Rate My Agent. With over $80 million sold since January this year, they have the experience and the proven track record to assist you with all your property needs. IF you are thinking oF selling or would like an update on the value oF your home call our team at McGrath Avalon. James Baker 0421 272 692 Lauren Garner 0403 944 427 Lyndall Barry 0411 436 407 mcgrath.com.au Avalon Sailing Club Mainsheet 2019 - 2020 Avalon Sailing Club Limited Old Wharf Reserve 28b Hudson Parade Clareville Beach “For the fostering, encouragement, promotion, teaching and above all, enjoyment of sailing on the waters of Pittwater” Mainsheet Postal Address: PO Box 59 Avalon Beach NSW 2107 Phone: 02 9918 3637 (Clubhouse) Sundays only Website: www.avalonsailingclub.com.au Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Avalon Sailing Club Mainsheet 2019 - 2020 Table of Contents Commodore’s Welcome ___________ 1 Sections 3 - Course B (Gold PM) ___ 38 General Club Facilities ____________ 2 Laser Full Rig, International 420, Clubhouse Keys and Security _____ 2 International 29er, Finn, Spiral, Flying Radios _______________________ 2 11 and O’pen Skiffs ____________ 38 Moorings _____________________ 2 Race Management ______________ 41 Sailing Training ________________ 2 A Guide for Spectator -

Filing Port Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Last

Filing Last Port Call Sign Foreign Trade Official Voyage Vessel Type Dock Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Last Domestic Port Vessel Name Last Foreign Port Number IMO Number Country Code Number Number Vessel Flag Code Agent Name PAX Total Crew Operator Name Draft Tonnage Owner Name Dock Name InTrans 5301 HOUSTON, TX 5301-2021-01647 1/1/2021 - GOLDENGATE PARK RIO JAINA D5EL2 9493145 DO 1 16098 64 LR 150 NORTON LILLY INTL 0 23 MADDSIN SHIPPING LTD. 18'0" 6115 MADDSIN SHIPPING LTD. ITC DEER PARK DOCK NO 7 L 2002 NEW ORLEANS, LA 2002-2021-00907 1/1/2021 HOUSTON, TX AS Cleopatra - V2DV3 9311787 - 6 4550 051N AG 310 NORTON LILLY INTERNATIONAL 3 17 AS CLEOPATRA SCHIFFAHRTSGESELLSCHAFT MBH & CO., KG 37'9" 13574 AS CLEOPATRA SCHIFFAHRTSGESELLSCHAFT MBH & CO., KG NASHVILLE AVENUE WHARVES A, B AND C DFLX 4106 ERIE, PA 4106-2021-00002 1/1/2021 - ALGOMA BUFFALO HAMILTON, ONT WXS6134 7620653 CA 1 841536 058 CA 600 WORLD SHIPPING INC. 0 20 ALGOMA CENTRAL CORPORATION CANADA 22'6" 5107 ALGOMA CENTRAL CORPORATION CANADA DONJON SHIPBUILDING & REPAIR N 2002 NEW ORLEANS, LA 2002-2021-00906 1/1/2021 HOUSTON, TX TEMPANOS - A8VP9 9447897 - 6 92780 2044N LR 310 NORTON LILLY INTERNATIONAL 2 26 HAPAG-LLOYD/ GERMANY 39'4" 42897 HULL 1794 CO. LTD NASHVILLE AVENUE WHARVES A, B AND C DFLX 1103 WILMINGTON, DE 1103-2021-00185 1/1/2021 PORTSMOUTH, NH HOURAI MARU - V7A2157 9796585 - 4 8262 1 MH 210 MORAN SHIPPING AGENCIES, INC 0 24 SYNERGY MARITIME PRIVATE LIMITED 23'4" 7638 SOUTHERN PACIFIC HOLDING CORPORATION SUNOCO MARCUS HOOK L 2904 PORTLAND, OR 2904-2021-00150 1/1/2021 - PAN TOPAZ KUSHIRO 3FMZ5 9625827 JP 1 43732-12-B 52 PA 229 transmarine navigation corp. -

By Bob Funkhouser Saddle Horse Report • August 14, 2017

by Bob Funkhouser t was a long plane ride from South Africa. Mark Turner was right out of high school, having grown up in Cradock on the eastern Cape. He had never seen a big airplane, much less been on one. With only a few dollars in his pocket the Iyoung man was going to a strange country, however, he was going with an incredible opportunity to help fulfill his dream of being a horse trainer. “I was first exposed to American Saddlebreds through my dad. He’s my biggest influence,” said Turner. “My older sister showed. My first horse was actually a jumper before I ever sat on a Saddlebred. He was a Gymkhana horse. We enjoyed horses as a family. Mom didn’t have any interest in riding but she made tail bags and things for us. We would trailer in and out and stay at the campgrounds. It was a big social outing. I didn’t even know you stayed at a horse show until I got here in the states.” 130 Saddle Horse Report • August 14, 2017 Finding A Home A Long Way From Home Through this gate and down this drive have gone some of the greatest horsemen, show ring champions,and producers the American Saddlebred industry has ever known. Although he loved horses from an early age, to South Africa to do a clinic. There was a South seeing all of her magnificent spotted horses in the training isn’t something Turner sought at first. He African Turner knew by the name of Chappy Scott magazine and we knew about Don Harris and Mitch thought for sure he was going to be a vet but he soon who was a friend of Bud’s and Scott asked Bud to Clark with Imperator and Sky Watch. -

Carnaby History

A / W 1 1 Contents Introduction C S W T S C A RN A BY IS KNO W N FOR UNIQUE INDEPENDENT BOUTIQUES , C ON C EPT STORES , GLOBA L FA SHION C F & D N Q BR A NDS , awa RD W INNING RESTAUR A NTS , ca FÉS A ND BA RS ; M A KING IT ONE OF L ONDON ' S MOST H POPUL A R A ND DISTIN C TIVE SHOPPING A ND LIFESTYLE DESTIN ATIONS . T K C S TEP UNDER THE IC ONIC C A RN A BY A R C H A ND F IND OUT MORE A BOUT THE L ATEST EXPERIEN C E THE C RE ATIVE A ND UNIQUE VIBE . C OLLE C TIONS , EVENTS , NE W STORES , T HE STREETS TH AT M A KE UP THIS STYLE VILL AGE RESTAUR A NTS A ND POP - UP SHOPS AT I F’ P IN C LUDE C A RN A BY S TREET , N E W BURGH S TREET , ca RN A BY . C O . UK . M A RSH A LL S TREET , G A NTON S TREET , K INGLY S TREET , M F OUBERT ’ S P L ac E , B E A K S TREET , B ROA D W IC K S TREET , M A RLBOROUGH C OURT , L O W NDES C OURT , G RE AT M A RLBOROUGH S TREET , L EXINGTON S TREET A ND THE VIBR A NT OPEN A IR C OURTYA RD , K INGLY C OURT . C A RN A BY IS LO caTED JUST MINUTES awaY FROM O XFORD C IR C US A ND P Icca DILLY C IR C US IN THE C ENTRE OF L ONDON ’ S W EST E ND . -

Connecticut Reports

CONNECTICUT R EPORTS: BEING R EPORTS OF CASES A RGUED AND DETERMINED INHE T SUPREME C OURT OF ERRORS OFHE T STATEF O CONNECTICUT. VOL. L IV. BY J OHN HOOKER. PUBLISHED F OR THE STATE OF CONNECTICUT, BY BAN KS & BR OTHERS, 144 NASSAUSTREET, NEW YORK. 1887. U(7// Entered a ccording to Act of Congress, in the year 1886, for the State of Connecticut, By C HARLES A. RUSSELL, SECRETARY OF THE STATE, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. * PREFATORY N OTE. In t he present volume the cases are printed in the order in which the opinions were filed without reference to the terms of the court. The date at the head of each page is that of the filing of the opinion. To each case is prefixed a memorandum of the county or district, of the term, and of the judges sitting, and at the foot of the head-note the dates of the argument and decision. It is proposed to pur sue the same course in the later volumes. The cause of the absence of any judge will not be noted, and where a judge of the Superior Court is called in to sit in a case his name will be given with the others without mentioning the fact that he is a judge of that court, leaving the reader to ascertain for himself by reference to the list of the judges of both courts which will be prefixed to the volume. J U D G E S OFHE T R.SU P E. -

H/W Or CP) TRS None None S and H/W Or CP) 48 None None None D Services Ltd

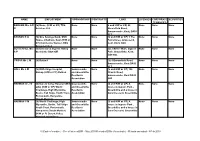

NAME EMPLOYMENT SPONSORSHIP CONTRACTS LAND LICENSES CORPORATE SECURITIES TENANCIES BARHAM Mrs A E (S) None, (H/W or CP) TRS None None S and H/W or CP) 48 None None None D Services Ltd. Broomfield Road, Swanscombe, Kent, DA10 0LT BASSON K G (S) One Savings Bank, OSB None None (S and H/W or CP) 1 The None None None House, Chatham, Kent.(H/W or Turnstones, Gravesend, CP) Call Centre Worker, RBS Kent, DA12 5QD Group Limited BUTTERFILL Mrs (S) Director at Ingress Abbey None None (S) 2 Meriel Walk, Ingress None None None S P Greenhthe DA9 9UR Park, Greenhithe, Kent, DA9 9GL CROSS Ms L M (S) Retired None None (S) 4 Broomfield Road, None None None Swanscombe, Kent DA10 0LT HALL Ms L M (S) NHS Kings Hospital, Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) 156 None None None Sidcup (H/W or CP) Retired and Greenhithe Church Road, Residents Swanscombe, Kent DA10 Association 0HP HARMAN Dr J M (S) Darent Valley Hospital (Mid- Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) A None None None wife) (H/W or CP) World and Greenhithe house in Ingress Park , Challenge, High Wycombe, Residents Greenhithe and a house in Bucks. Tall Ships Youth Trust, Association Sara Crescent, Greenhithe Portsmouth, Hampshire (Youth Mentor) HARMAN P M (S) World Challenge, High Swanscombe None (S and H/W or CP) A None None None Wycombe, Bucks. Tall Ships and Greenhithe house in Ingress Park , Youth Trust, Portsmouth, Residents Greenhithe and a house in Hampshire (Youth Mentor) Association Sara Crescent, Greenhithe (H/W or P) Darent Valley Hospital (midwifery) V:\Code of conduct - Dec of Interest\DPI - May 2015\Record of DPIs (for website) - PHarris amended - 8 Feb 2018 HARRIS PC (S) Retired. -

The General Stud Book : Containing Pedigrees of Race Horses, &C

^--v ''*4# ^^^j^ r- "^. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 witii funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/generalstudbookc02fair THE GENERAL STUD BOOK VOL. II. : THE deiterol STUD BOOK, CONTAINING PEDIGREES OF RACE HORSES, &C. &-C. From the earliest Accounts to the Year 1831. inclusice. ITS FOUR VOLUMES. VOL. II. Brussels PRINTED FOR MELINE, CANS A.ND C"., EOILEVARD DE WATERLOO, Zi. M DCCC XXXIX. MR V. un:ve PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. To assist in the detection of spurious and the correction of inaccu- rate pedigrees, is one of the purposes of the present publication, in which respect the first Volume has been of acknowledged utility. The two together, it is hoped, will form a comprehensive and tole- rably correct Register of Pedigrees. It will be observed that some of the Mares which appeared in the last Supplement (whereof this is a republication and continua- tion) stand as they did there, i. e. without any additions to their produce since 1813 or 1814. — It has been ascertained that several of them were about that time sold by public auction, and as all attempts to trace them have failed, the probability is that they have either been converted to some other use, or been sent abroad. If any proof were wanting of the superiority of the English breed of horses over that of every other country, it might be found in the avidity with which they are sought by Foreigners. The exportation of them to Russia, France, Germany, etc. for the last five years has been so considerable, as to render it an object of some importance in a commercial point of view. -

Anglo-Jewry's Experience of Secondary Education

Anglo-Jewry’s Experience of Secondary Education from the 1830s until 1920 Emma Tanya Harris A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements For award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies University College London London 2007 1 UMI Number: U592088 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U592088 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract of Thesis This thesis examines the birth of secondary education for Jews in England, focusing on the middle classes as defined in the text. This study explores various types of secondary education that are categorised under one of two generic terms - Jewish secondary education or secondary education for Jews. The former describes institutions, offered by individual Jews, which provided a blend of religious and/or secular education. The latter focuses on non-Jewish schools which accepted Jews (and some which did not but were, nevertheless, attended by Jews). Whilst this work emphasises London and its environs, other areas of Jewish residence, both major and minor, are also investigated.