The Index of Global Philanthropy and Remittances 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Brokering Inclusive Business Models” (2010)

Private Sector Division, UNDP: “Brokering Inclusive Business Models” (2010) This series also includes: Inclusive Markets Development Handbook (2010) And the following supporting tools: Private Sector Division, UNDP: “Assessing Markets” (2010) Private Sector Division, UNDP: “Guide to Partnership Building” (2010) This document was produced for the Private Sector Division, Partnership Bureau, UNDP Authors: Christina Gradl and Claudia Knobloch, Emergia Institute Design: Rodrigo Domingues Copyright © 2010 United Nations Development Programme One United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, including UNDP, or their Member States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without prior permission of the United Nations Development Programme. Brokering Inclusive Business Models – Private Sector Division, Partnerships Bureau, UNDP 2 Preface This primer is written for brokers of inclusive business models, the people who provide the connecting tissue between companies, communities and development organizations, between business and human development, between business strategy and development expertise. The role of the broker is essential even though often hardly visible. Success for a broker means ensuring ownership with companies and partner organizations, the creation of a self-sustainable business model, it basically means becoming superfluous. And yet, brokers often provide the initial spark, the access to partners and resources, the ongoing motivation, support and advice that make inclusive business models succeed. We hope that this primer can support them in this important endeavour. -

Download/Fedora Content/Download/Ac:100224/C ONTENT/Econ 9495 757.Pdf Persson, T

FONDAZIONE “CENTESIMUS ANNUS – PRO PONTIFICE” — 11 — © Copyright 2017 – Libreria Editrice Vaticana 00120 Città del Vaticano Tel. 06 69 88 10 32 – Fax 06 69 88 47 16 www.libreriaeditricevaticana.va www.vatican.va ISBN 978-88-209-8095-5 Inclusive Growth and Financial Reforms: Global Emergencies and the Search of the Common Good Edited by Giovanni Marseguerra Anna Maria Tarantola LIBRERIA EDITRICE VATICANA “CENTESIMUS ANNUS – PRO PONTIFICE” FOUNDATION Board of Directors SUGRANYES BICKEL Dr. Domingo (Chairman) BORGHESE KHEVENHUELLER Dr. Camilla (Vice Chairman) GONZI Dr. Lawrence LONGHI Dr. Gianluigi RICE Dr. James E. RUSCHE Dr. Thomas SANSONE Dr. Francesco TARANTOLA Dr. Anna Maria (Delegate of the Board for the Scientifi c Committee) VANNI D’ARCHIRAFI Dr. Francesco Comptrollers FRANCESCHI Dr. Giorgio PIZZINI Dr. Flavio PORFIRI Dr. Massimo Secretary General TILIACOS Dr. Eutimio Scientifi c Committee MARSEGUERRA Prof. Giovanni (Coordinator) PABST Prof. Adrian (Secretary) ABELA Prof. Andrew V. Ph.D BONNICI Prof. Josef COSTA Prof. Antonio Maria DEMBINSKI Prof. Paul ESTRADA Prof. Francis G. GARONNA Prof. Paolo GARVEY Prof. George E. GIOVANELLI Dr. Flaminia NOTHELLE-WILDFEUER Prof. Ursula PAMMOLLI Prof. Fabio PASTOR Prof. Alfredo PEZZANI Prof. Fabrizio ZANUSSI Prof. Krystof VOLUME’S ABSTRACT The book collects contributions presented and discussed during International Conferences and Consultations organ- ized by the “Centesimus Annus – Pro Pontifi ce” Foundation (CAPPF) in the two-year period 2015 – 2016. In particular, articles here reported derive from two International Confer- ences held in the Vatican (“Rethinking Key Features of Eco- nomic and Social Life”, 25-27 May 2015, and “Business initiative in the fi ght against poverty. The Refugee Emergency, our Chal- lenge”, 12-14 May 2016) and an International Consultation held in Malta (“A Dialogue on Finance and the Common Good”, 29-30 January 2016). -

Request for Proposals to Provide Documentary Filming And

Request for Proposals to Provide Documentary Filming and Production Services to the Pioneers of Prosperity Program Deadline for submission – April 10, 2009 Start date – April 15, 2009 Background: Research indicates that a key constraint to economic growth in the Caribbean is a low level of entrepreneurship, or low support (technical, access to financing, policy environment) for entrepreneurs who are trying to start, or build, their businesses. Pioneers of Prosperity is founded on the fact that innovative ideas and dynamic business models exist in even the most challenging markets, and that greater prosperity will ensue if these local models of success are better understood, better supported, and showcased widely. Pioneers of Prosperity (PoP) is a global awards program that seeks to inspire a new generation of entrepreneurs in emerging economies by identifying, rewarding, and promoting truly outstanding businesses that can serve as role models to their peers. Unlike other award programs, PoP does not end with the distribution of the award. Rather, the award is just the beginning. PoP will focus on post-award communication efforts to showcase the winning firms and connect participants to networks of other entrepreneurs, technical expertise, and financial capital, and inspire a culture of entrepreneurship and innovation. To create greater prosperity in the Caribbean, PoP will: 1. Identify existing small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that create value for their customers, owners, workers and future generations (i.e. their four key stakeholders). 2. Invest in their business models with a grant to apply towards technical infrastructure and training for their company, and by connecting them to networks of technical expertise and financial capital. -

Download Download

De Ethica. A Journal of Philosophical, Theological and Applied Ethics Vol. 2:3 (2015) The Rise of Religion and the Future of Capitalism Peter S. Heslam The rise of religion and the rise of capitalism are currently occurring in roughly the same geographical regions (Latin America, Asia, and Africa). Although both religion and capitalism are often ignored, or are regarded negatively, within development circles, this article reflects on their potential for human wellbeing when they convergence. Its focus is on the socio-economic significance of what the author calls the Evangelical Pentecostal Charismatic Movement (EPCM), which accounts for most of the growth of Christianity, the world’s largest religion. He argues that the movement’s stimulation of self- empowerment (especially of women), church-based social outreach, and the encouragement of trust are of particular significance. They provide ample grounds, he contends, for revisiting the question Max Weber is famous for having posed about the link between religious belief and economic behaviour. They also help overcome victimhood mentalities and promote good stewardship, accountability and integrity. The EPCM thereby acts as a progressive force that, in serving the common good, stands to make a positive contribution to the future of capitalism. One of the futures of capitalism reflects one of its pasts: it will be driven and shaped by religious belief. The context for this claim is a world in which the areas experiencing the rise of entrepreneurial capitalism roughly correspond to those experiencing the rise of religion. This observation recalls the work of the German academic Max Weber (1864- 1920), generally regarded as the chief founder of sociology. -

ITTO Tropical Timber Market Report

Tropical Timber Market Report since 1990 Volume 14 Number 15, 1-15 August 2009 The ITTO Tropical Timber Market (TTM) Report, an output of the ITTO Market Information Service (MIS), is published in English every two weeks with the aim of improving transparency in the international tropical timber market. Its contents do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ITTO. News may be reprinted without charge provided that the ITTO TTM Report is credited. A copy of the publication should be sent to the editor. Snapshot Headlines Reports over the last fortnight indicated slow business as Ghana’s Ayum sets pace for best timber practices 2 the summer holidays in Europe continued. Further results from the first half of 2009 showed the impacts of the Trade event in Malaysia expected to draw 50,000 visitors 3 financial crisis. Sengon used as alternative to raw materials from production forests 4 Brazil’s northern state of Pará reported a 53% drop in exports of solidwood products during the first half of Indonesian Ministries wrangle over rattan quotas 5 2009. China indicated a 21% fall in forest products Active purchasing points to market recovery in Myanmar 5 imports and an 11.7% decline in exports of forest products during the same period. US imports of tropical India housing sector gets boost from government measures 6 timber during the January to May 2009 period slid to about half their value from the same period in 2008. Brazil offers national forests for auction 7 Nevertheless, Canada reported a slight upturn in its Mexico aims to restore degraded land 9 housing market. -

A Powerful and Uncompromising Film That Strikes at The

POVERTYCURE, ACTON MEDIA, AND COLDWATER MEDIA PRESENT “A powerful and uncompromising flm that strikes at the core of the traditional understanding of development and international assistance.” - Andres Jimenez, Waging Non-Violence [Costa Rica] DIRECTED AND PRODUCED BY MICHAEL MATHESON MILLER DOCUMENTARY, 91 MIN. (55 MIN. VERSION AVAILABLE) DISTRIBUTED BY RO*CO FILMS INTERNATIONAL TUGG, INC. BRAINSTORM MEDIA WWW.POVERTYINC.ORG #POVERTYINC [email protected] Logline The West has positioned itself as the protagonist of development, giving rise to a vast multi- billion dollar poverty industry of for-proft aid contractors and massive NGOs — the business of doing good has never been better. Yet the results have been mixed and leaders in the developing world are calling for change. From TOMs Shoes to international adoptions, from solar panels to U.S. agricultural subsidies, POVERTY, INC. challenges each of us to ask the tough question: Could I be part of the problem? Synopsis “I see multiple colonial governors,” says Ghanaian software entrepreneur Herman Chinery- Hesse of the international development establishment in Africa. “We are held captive by the donor community.” The West has positioned itself as the protagonist of development, giving rise to a vast multi- billion dollar poverty industry — the business of doing good has never been better. Yet the results have been mixed, in some cases even catastrophic, and leaders in the developing world are growing increasingly vocal in calling for change. Drawing from over 200 interviews flmed in 20 countries, Poverty, Inc. unearths an uncomfortable side of charity we can no longer ignore. From TOMs Shoes to international adoptions, from solar panels to U.S. -

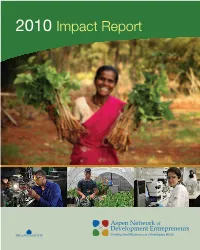

Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs 2010 Impact Report

2010 Impact Report Cover Photos (John-Michael Maas/Darby Communications): A woman gathers jatropha which will be used to generate biofuel by Nandan Biomatrix Limited. New Ventures India supports Nandan by providing mentoring and technical assistance. A toolmaker at Dramco Tooling CC works on a thermo-forming mold. Swisscontact is helping Dramco increase their competitiveness in the South African tool and die market. A resident of Cheshire Homes harvests lettuce from a FoodTent. Heart Capital has over 70 sites with FoodTents, 3 GrowZones (agri-businesses), and feeds over 3,000 people per month in Cape Town, South Africa. A lab technician at Biovac develops vaccines for the South African market. ATMS Foundation/AMSCO has supported Biovac by bringing in an international bioengineer to help develop local capacity for vaccination production. Dear ANDE Friends and Colleagues, I am pleased to present you with the second annual Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) Impact Report. As was the case in our inaugural year, the growth of ANDE has surpassed our expectations. Today, our membership exceeds 110 organizations that operate in 150 developing countries. Our members truly span the world. More importantly, they are deeply committed to working together to promote entrepreneurship in emerging markets. All of our events, including our annual conference, investment manager training, London summit, metrics conference, and orientation training, continue to exceed attendee projections (and sometimes capacity). At the 2010 Annual Conference in New York, more than 140 participants from 70-plus organizations and 17 countries convened to share experiences, forge new alliances, and advance ongoing ANDE initiatives and working groups. -

Kenyan Woman MARCH 8, 2014 Kenyan Woman

INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY KENYAN WOMAN MARCH 8, 2014 KENYAN WOMAN SPECIAL ISSUEInspiring Change INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY | MARCH 8, 2014 Women walking back to their homes in Gumuruk, Pibor County, Jonglei State. PICTURE: PLAN INTERNATIONAL KENYAN WOMAN INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY KENYAN WOMAN 2 MARCH 8, 2014 MARCH 8, 2014 3 Another key intervention includes the Road to equality 30 percent affirmative action for women and youth to access procurement Road to equality remains bumpy for Kenyan women remains bumpy tenders advertised by the government. of Constitutional commissions, six Challenges Despite the percent of parastatal heads, 13 per for Kenyan cent of county secretaries and 21 per Sadly, however, although the country’s cent of county assembly clerks. women Government recently said all maternity services in public hospitals will be progressive and free, the Kenya Position Paper for the In class: Framework << from page 2 because ideally, they 58th Session on the Commission on Kenya makes gender sensitive As we seek meaning today around should be similar to the Status of Women says the Kenya what this day signifies, there is need those of elected members. significant Demographic Health Survey report gains in constitution, to fully operationalise the Constitution Her sentiments are echoed by Prof does not paint a good picture. It notes and enact laws that seek to ensure Wanjiku Kabira who notes that education as that while in 2003 there 414 deaths gender equality gender equity in major decision making affirmative action clause is a critical scores of girls per 100,000, this increased to 488 in organs. -

Social/Environmental and Sustainability Practices 2017

SOCIAL/ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY PRACTICES Prepared By: Rev-00 Date Revision No. Reviewed By Reviewed By Prepared/Authorized By (dd/mm/yy) Rev-00 Robin V. Strachan Sr. Ricardo L. Bonaby Ray R. McKenzie 24 April 2018 Signatures This document was created to describe Caribbean Civil Group Ltd.’s(CCG) Social, Environmental and Sustainability Practices Procedure in accordance with the company’spolicies and standards. This QSP document should not be used for any other purpose other than which it was intended. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO CARIBBEAN CIVIL GROUP ......................................................................1 PURPOSE ....................................................................................................................................2 SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGY.....................................................................................................2 1. KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS ...................................................................................3 2. THE CCG TEAM ...................................................................................................................6 3. CORPORATE PHILANTROPHY...........................................................................................6 4. SUB-CONSULTANT EVALUATION......................................................................................7 5. GOING FORWARD ...............................................................................................................8 24 April 2018 Rev-00 CCG Social/Environmental -

Memory, Race, and Coloniality

COSMOPOLITAN MEANDERICITY: SURINAMESE ENTANGLEMENTS OF MEMORY, RACE, AND COLONIALITY Doctoral Thesis by Praveen Sewgobind Research Training Group Minor Cosmopolitanisms University of Potsdam Submitted to the Faculty of Arts at the University of Potsdam in the year 2019 2 I hereby declare that this dissertation has been prepared independently, that I only used the resources stated in this dissertation, and that all text and contents have been referenced properly. Praveen Sewgobind 3 This book is dedicated to my parents and all other meandering members of the Sewgobind and Kisoensingh families 4 TABLE OF CONTENT PREFIX.........................................................................................................................................6 PREFACE.....................................................................................................................................9 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS........................................................................................................11 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................13 CHAPTER ONE: THEORETICAL ENTANGLEMENTS........................................................33 CHAPTER TWO: HISTORICAL ENTANGLEMENTS OF HINDUSTANI...........................89 CHAPTER THREE: ANIL RAMDAS.....................................................................................172 CHAPTER FOUR: HINDUSTANI AND AFRO-SURINAMESE COLONIALITIES..........289 CONCLUSION.........................................................................................................................446 -

2010 Impact Report Cover Photos (John-Michael Maas/Darby Communications): a Woman Gathers Jatropha Which Will Be Used to Generate Biofuel by Nandan Biomatrix Limited

2010 Impact Report Cover Photos (John-Michael Maas/Darby Communications): A woman gathers jatropha which will be used to generate biofuel by Nandan Biomatrix Limited. New Ventures India supports Nandan by providing mentoring and technical assistance. A toolmaker at Dramco Tooling CC works on a thermo-forming mold. Swisscontact is helping Dramco increase their competitiveness in the South African tool and die market. A resident of Cheshire Homes harvests lettuce from a FoodTent. Heart Capital has over 70 sites with FoodTents, 3 GrowZones (agri-businesses), and feeds over 3,000 people per month in Cape Town, South Africa. A lab technician at Biovac develops vaccines for the South African market. ATMS Foundation/AMSCO has supported Biovac by bringing in an international bioengineer to help develop local capacity for vaccination production. Dear ANDE Friends and Colleagues, I am pleased to present you with the second annual Aspen Network of Development Entrepreneurs (ANDE) Impact Report. As was the case in our inaugural year, the growth of ANDE has surpassed our expectations. Today, our membership exceeds 110 organizations that operate in 150 developing countries. Our members truly span the world. More importantly, they are deeply committed to working together to promote entrepreneurship in emerging markets. All of our events, including our annual conference, investment manager training, London summit, metrics conference, and orientation training, continue to exceed attendee projections (and sometimes capacity). At the 2010 Annual Conference in New York, more than 140 participants from 70-plus organizations and 17 countries convened to share experiences, forge new alliances, and advance ongoing ANDE initiatives and working groups.