Forest Rights Act Implementation and Tribal Livelihoods: a Community-Based Field Study in Jharkhand, India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jharkhand Report No 4 of 2016 Revenue Sector

Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Revenue Sector for the year ended 31 March 2016 Government of Jharkhand Report No. 4 of the year 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph Page Preface v Overview vii CHAPTER – I: GENERAL Trend of receipts 1.1 1 Analysis of arrears of revenue 1.2 5 Arrears in assessments 1.3 6 Evasion of tax detected by the Department 1.4 7 Pendency of Refund Cases 1.5 7 Response of the Departments/Government towards Audit 1.6 8 Analysis of mechanism for dealing with issues raised by 1.7 11 Audit Audit execution for the financial year 2015-16 1.8 12 Results of audit 1.9 13 Coverage of this Report 1.10 13 CHAPTER – II: TAXES ON SALES, TRADE ETC. Tax administration 2.1 15 Results of Audit 2.2 15 Implementation of mechanism of cross-verification of VAT/CST transactions in Commercial Taxes 2.3 17 Department System of collection of arrears of revenue in 2.4 28 Commercial Taxes Department in Jharkhand Irregularities in determination of actual turnover 2.5 46 Interest not levied 2.6 48 Irregularities in compliance to the Central Sales Tax Act 2.7 51 Application of incorrect rate of tax under JVAT Act 2.8 53 Incorrect exemptions 2.9 54 Irregularities in grant of Input Tax Credit (ITC) 2.10 55 Purchase tax was not levied 2.11 56 Penalty not imposed 2.12 57 CHAPTER – III: STATE EXCISE Tax administration 3.1 59 Results of Audit 3.2 60 Provision of Acts/Rules not complied with 3.3 61 Retail liquor shops not settled 3.4 61 Short lifting of liquor by retail vendors 3.5 62 i Audit Report for the year ended 31 March 2015 -

History of Jharkhand Movement: Regional Aspiration Has Fulfilled Yet

Indian J. Soc. & Pol. 06 (02):33-36 : 2019 ISSN: 2348-0084(P) ISSN: 2455-2127(O) HISTORY OF JHARKHAND MOVEMENT: REGIONAL ASPIRATION HAS FULFILLED YET AMIYA KUMAR SARKAR1 1Research Scholar, Department of Political Science, Adamas University Kolkata, West Bengal, INDIA ABSTRACT This paper attempts to analyze the creation of Jharkhand as a separate state through the long developmental struggle of tribal people and the condition of tribal‟s in the post Jharkhand periods. This paper also highlights the tribal movements against the unequal development and mismatch of Government policies and its poor implementations. It is true that when the Jharkhand Movement gaining ground these non-tribal groups too became part of the struggle. Thus, Jharkhandi came to be known as „the land of the destitute” comprising of all the deprived sections of Jharkhand society. Hence, development of Jharkhand means the development of the destitute of this region. In reality Jharkhand state is in the grip of the problems of low income, poor health and industrial growth. No qualitative change has been found in the condition of tribal people as the newly born state containing the Bihar legacy of its non-performance on the development front. KEYWORDS: Regionalism, State Reconstruction, Jharkhand Movement INTRODUCTION 1859, large scale transference of tribal land into the hands of the outsiders, the absentee landlords has taken place in the The term Jharkhand literally means the land of forest, entire Jharkhand region, especially in Chotanagpur hill area. geographically known as the Chhotanagpur Plateau; the region is often referred to as the Rurh of India. Jharkhand was earlier The main concern of East India Company and the a part of Bihar. -

Jh G Ha Go Ar Odd Kh Da Ha a and D

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF SAND GOGODDADA JHHAARKHAHAND Content Table Sl. Content Page No. No. 1. Introduction 2-3 2. Overview of Mining Activity in the District 3 3. The List of Mining Leases in the District with 4-9 location, area and period of validity 4. Details of Royalty or Revenue received in last three 9 years 5. Detail of Production of Sand or Bajari or minor 9 mineral in last three years 6. Process of Deposition of Sediments in the rivers of 9-10 the District 7. General Profile of the District 10 8. Land Utilization Pattern in the district: Forest, 10 Agriculture, Horticulture, Mining etc. 9. Physiography of the District 11-12 10. Rainfall: month-wise 13 11. Geology and Mineral Wealth 13-16 12. General Recommendations 17-18 12. Annexure- I 19-22 13. Annexure- II 23-24 14. Annexure- III 25 INTRODUCTION: As per the guidelines issued in Para 7 (iii) of Part-II- Section-3-Sub Section (ii) of Extraordinary Gazette of MoEF&CC, Government of India, New Delhi dated 15.01.2016 and in concurrence to directives issued by the Chief Secretary to Government, Government of Jharkhand vide letter no. 1874/C.S. dated 01/08/17 a District Survey Report (DSR) is to be prepared for each district in Jharkhand. The main spirit of preparing this report is to encourage Sustainable Mining and development. In this direction a team comprising of Mines and Geology, Irrigation, or Remote Sensing departments were given the task for preparing this report. An extensive field work was carried on 28/08/2017 and 29/08/2017 by the members of the committee to assess the possibilities of sand mining in the Godda district. -

BA Semester VI- the Lower Section Society Movement (Peasant, Labour and Lower Caste)- (HISKB 604)

BA Semester VI- The Lower Section Society Movement (Peasant, Labour and Lower Caste)- (HISKB 604) Dr. Mukesh Kumar (Department of History) KMC Language University Lucknow, U.P.-22013 UNIT-I Revolt in Bengal and Eastern India- The establishment and spread of the East India Company's rule in Bengal and its adjoining areas resulted in many civil rebellions and tribal uprisings beginning from the latter half of the eighteenth century. The British rule in Bengal after 1757 brought about a new economic order which was disastrous for the zamindars, peasants, and artisans alike. The famine of 1770 and the callousness on the part of the Company to redress the sufferings of the common man were seen as direct consequences of the alien rule. Sanyasi Revolt: Also known as the Sanyasi-Fakir rebellion, it was a confrontation between armed wandering monks and the Company's forces in Bengal and Bihar which began in the 1760s and continued until the middle of 1800s. These groups were severely affected by the high revenue demands, resumption of rent-free tenures, and commercial monopoly by the Company. The Company also placed restrictions on their access to holy places. This resulted in organized raids by the sanyasis on the Company's factories and state treasuries in retaliation. Only after prolonged military actions, this revolt was contained. Chuar Uprising: Famine, enhanced land revenue demands, and economic distress forced the Chuar tribesmen of Midnapur district to take up arms against the Company. The revolted lasted from 1766 to 1772 and then again surfaced between 1795 and 1816. 1 Ho Uprising: The Ho and Munda tribesmen of Chhota Nagpur and Singhbhum challenged the Company's forces in 1820-1822, again in 1831 and the area remained disturbed till 1837. -

Cbcs Curriculum of Ma History Programme

CBCS CURRICULUM OF M.A. HISTORY PROGRAMME SUBJECT CODE = HIS FOR POST GRADUATE COURSES UNDER RANCHI UNIVERSITY Implemented from Academic Session 2018-2020 PG: HISTORY CBCS CURRICULUM RANCHI UNIVERSITY Members of Board of Studies for CBCS Syllabus of PG History, Under Ranchi University, Ranchi. Session 2018-20 Onwards i PG: HISTORY CBCS CURRICULUM RANCHI UNIVERSITY Contents S.No. Page No. Members of Core Committee I Contents ii COURSE STUCTURE FOR POSTGRADUATE PROGRAMME 1 Distribution of 80 Credits 1 2 Course structure for M.A. in HISTORY 1 3 Semester wise Examination Structure for Mid Semester & End Semester 2 Examinations SEMESTER I 4 I FC-101 Compulsory Foundation Course (FC) 3 5 II. CC-102 Core Course –C 1 5 6 III. CC-103 Core Course –C 2 7 7 IV CC-104 Core Course –C 3 9 SEMESTER II 8 I CC-201 Core Course- C 4 11 9 II. CC-202 Core Course- C 5 13 10 III. CC-203 Core Course –C 6 15 11 IV CC-204 Core Course –C 7 17 SEMESTER III 12 I EC-301 Ability Enhancement Course (AE) 19 13 II. CC-302 Core Course –C 8 21 14 III. CC-303 Core Course- C 9 23 15 IV CC-304 Core Course –C 10 25 SEMESTER IV 16 I EC-401 Generic/Discipline Elective (GE/DC 1) 27 17 II. EC-402 Generic/Discipline Elective (GE/DC 2) 33 18 III. CC-403 Core Course –C 11 39 19 IV PR-404 Core Course (Project/ Dissertation) –C 12 41 ANNEXURE 20 Distribution of Credits for P.G. -

Dto Name Jun 2016 Jun 2016 1Regn No V Type

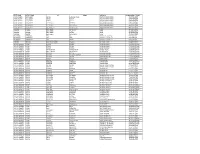

DTO_NAME JUN_2016 JUN_2016_1REGN_NO V_TYPE TAX_PAID_UPTO O_NAME F_NAME ADD1 ADD2 CITY PINCODE STATUS TAX_AMOUNT PENALTY TOTAL RANCHI N N JH01BZ8715 BUS 19-08-16 KRISHNA KUMHARS/O LATE CHHOTUBARA MURIKUMHAR CHHOTASILLI MURI RANCHI SUCCESS 6414 1604 8018 RANCHI N N JH01G 4365 BUS 15-08-16 ASHISH ORAONS/O JATRU ORAONGAMARIYA SARAMPO- MURUPIRIRANCHI -PS- BURMU 000000 SUCCESS 5619 1604 7223 RANCHI N N JH01BP5656 BUS 29-06-16 SURESH BHAGATS/O KALDEV CHIRONDIBHAGAT BASTIBARIATU RANCHI SUCCESS 6414 6414 12828 RANCHI N N JH01BC8857 BUS 22-07-16 SDA HIGH SCHOOLI/C HENRY SINGHTORPA ROADKHUNTI KHUNTI , M- KHUNTI9431115173 SUCCESS 6649 3325 9974 RANCHI Y Y JH01BE4699 BUS 21-06-16 DHANESHWARS/O GANJHU MANGARSIDALU GANJHU BAHERAPIPARWAR KHELARIRANCHI , M- 9470128861 SUCCESS 5945 5945 11890 RANCHI N N JH01BF8141 BUS 19-08-16 URSULINE CONVENTI/C GIRLSDR HIGH CAMIL SCHOOL BULCKERANCHI PATH , M- RANCHI9835953187 SUCCESS 3762 941 4703 RANCHI N N JH01AX8750 BUS 15-08-16 DILIP KUMARS/O SINGH SRI NIRMALNEAR SINGH SHARDHANANDANAND NAGAR SCHOOLRANCHI KAMRE , M- RATU 9973803185SUCCESS 3318 830 4148 RANCHI Y Y JH01AZ6810 BUS 12-01-16 C C L RANCHII/C SUPDT.(M)PURCHASE COLLY MGR DEPARTMENTDARBHANGARANCHI HOUSE PH.NO- 0651-2360261SUCCESS 19242 28862 48104 RANCHI Y Y JH01AK0808 BUS 24-04-16 KAMAKHYA NARAYANS/O NAWAL SINGH KISHORECHERI KAMRE NATHKANKE SINGH RANCHI SUCCESS 4602 2504 7106 RANCHI N N JH01AE6193 BUS 04-08-16 MRS. GAYTRIW/O DEVI SRI PRADEEPKONBIR KUMARNAWATOLI GUPTA BASIAGUMLA SUCCESS 4602 2504 7106 RANCHI Y Y JH01AE0222 BUS 22-06-16 RANCHI MUNICIPALI/C CEO CORPORATIONGOVT OF JHARKHANDRANCHI RANCHI SUCCESS 2795 3019 5814 RANCHI N N JH01AE0099 BUS 06-07-16 RANCHI MUNICIPALI/C CEO CORPN.GOVT. -

Sidhu and Kanhu

© 2019 JETIR May 2019, Volume 6, Issue 5 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) The Literary (Re)Presentation of the Tribal Heroes: Sidhu and Kanhu Teresa Tudu Assistant Professor Department of English Avvaiyar Government College for Women, Karaikal, Puducherry (Senior Research Fellow, BHU) Abstract The Santhal Revolt of 1855-56, also considered as the first peasant movement, was led by two young Santhals- Sidhu and Kanhu. This revolt which was believed to be guided by their God- ‘Thakur’ was aimed to get rid of the clutches of oppressive ‘Dikus’ and the Outsiders viz. Britishers. These two leaders, who have now acquired the status of gods and are worshipped by their tribesmen, have been extensively researched and written about. Even, they have been significantly mentioned in the stories, novels, poems, and songs. Although, they have been highly venerated by their tribesmen, some authors, and administrators of Colonial period differ in their opinion of these heroes. They have pointed out some drawbacks in their character and tried to showcase them merely as common men. This paper is aimed to critically analyze the personality of these two tribal leaders- Sidhu and Kanhu with the help of their portrayal in the available literature. This would lead us to draw a transparent and authentic image of these leaders. Keywords: Tribals, Revolt, Leaders, Hero-worship, Literature. I. INTRODUCTION Every year on 30th June Santhal folks celebrate Hool diwas commemorating their brave leaders of ‘Santhal Rebellion’ of 1855, Sidhu and Kanhu. Thousands of Santhals gather at Bhognadih, the birth place of Sidhu and Kanhu, and the Santhal rebellion. -

Jharkhand.Pdf

F. No. 13-1l2020-IS-15 Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department ofSchool Education & Literacy IS-15 Section **** Dated 22 June, 2020 Subiect: Samagra Shiksha: The Meeting of Proiect Approval Board (PAB) held on 29ttt April, 2020 for the State oflharkhand- Circulation of Minutes. The meeting of the Project Approval Board (PAB) for considering the Annual Work Plan and Budget (AWP&B),2020-?1 for SAMAGRA SHIKSHA, for the State of fharkhand, was held under the chairpersonship of Secretary (SE&L) on 296 April, 2020 through Video Conference. 2. A copy ofthe Minutes ofthe Meeting is enclosed. aLl6lwaPw'- "/----4(Kamal Gandhi) Under Secretary to the Government of lndia Tel. No. 011.-23070450 To, 1. Shri Aiay Tirkey, Secretary, Ministry of W & C.D. 2 Shri Heeralal Samariya, Secretary, Ministry of Labour & Employment. Shri R. Subrahmanyam, Secretary, Ministry of Social lustice & Empowerment. 4 Shri Deepak Khandekar Secretary, Ministry of Tribal Affairs 5 Shri Parameswaran Iyer, Secretary, Ministry of Drinking Water & Sanitation, 4th Floor, Paryavaran Bhavan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003. 6 Shri Pramod Kumar Das, Secretary, Ministry of Minority Affairs, 11s Floor, Paryavaran Bhavan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003. 7 Ms. Shakuntala D. Gamlin, Secretary, Department of Empowerment of persons With Disabilities, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment. I Dr. Poonam Srivastava, Dy. Adviser (EducationJ, NITI Aayog. 9 Prof. Hrushikesh Senapaty Director, NCERT. 10 Prof. N.V. Varghese, Vice Chancellor, NIEPA. 11. Chairperson, NCTE, Hans Bhawan, Wing II, 1 Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi - tL0002. 1.2 Prof. Nageshwar Rao, Vice Chancellor, IGN0U, Maidan Garhi, New Delhi. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme W Volume 1) (Kolebira GSS) Public Disclosure Authorized Jharkhand Urja Sancharan Final Report Nigam Limited September 2018 www.erm.com The Business of Sustainability FINAL REPORT Jharkhand Urja Sancharan Nigam Limited Environment and Social Impact Assessment Report (Scheme W Volume 1) (Kolebira GSS 14 August 2018 Reference # 0402882 Prepared by : Indrani Ghosh, Abhishek Roy Goswami Reviewed & Debanjan Approved by: Bandyapodhyay Partner This report has been prepared by ERM India Private Limited a member of Environmental Resources Management Group of companies, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence within the terms of the Contract with the client, incorporating our General Terms and Conditions of Business and taking account of the resources devoted to it by agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. This report is confidential to the client and we accept no responsibility of whatsoever nature to third parties to whom this report, or any part thereof, is made known. Any such party relies on the report at their own risk. TABLE OF CONTENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 PROJECT OVERVIEW 1 1.3 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THIS ESIA 2 1.4 STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT 2 1.5 LIMITATION 3 1.6 USES OF THIS REPORT 3 2 POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAME WORK 5 2.1 APPLICABLE LAWS AND STANDARDS -

Topics in Ho Morphosyntax and Morphophonology

TOPICS IN HO MORPHOPHONOLOGY AND MORPHOSYNTAX by ANNA PUCILOWSKI A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2013 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anna Pucilowski Title: Topics in Ho Morphophonology and Morphosyntax This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Linguistics by: Dr. Doris Payne Chair Dr. Scott Delancey Member Dr. Spike Gildea Member Dr. Zhuo Jing-Schmidt Outside Member Dr. Gregory D. S. Anderson Non-UO Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/ Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2013 ii c 2013 Anna Pucilowski iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Anna Pucilowski Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics June 2013 Title: Topics in Ho Morphophonology and Morphosyntax Ho, an under-documented North Munda language of India, is known for its complex verb forms. This dissertation focuses on analysis of several features of those complex verbs, using data from original fieldwork undertaken by the author. By way of background, an analysis of the phonetics, phonology and morphophonology of Ho is first presented. Ho has vowel harmony based on height, and like other Munda languages, the phonological word is restricted to two moras. There has been a long-standing debate over whether Ho and the other North Munda languages have word classes, including verbs as distinct from nouns. -

Revised Annual Action Plan: 2014-15 ICDS Systems Strengthening & Nutrition Improvement Project (ISSNIP)

Revised Annual Action Plan: 2014-15 ICDS Systems Strengthening & Nutrition Improvement Project (ISSNIP) [Credit 5150-IN] January 2015 Department of Social Welfare, Women and Child Development Government of Jharkhand Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction 1.1 Background ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 1.2 Project Development Objectives ………………………………………………………………… 7 1.3 Project Components ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 1.4 Information about Jharkhand …………………………………………………………………… 9 1.5 Project Coverage ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 13 1.6 District-wise details of beneficiaries ………………………………………………………………………… 14 1.7 Details of ISSNIP districts ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 15 1.8 Components and Year-wise allocation for phase I ………………………………………………. 30 1.9 Triggers for Phase I ………………………………………………………………………………………………... 31 Section 2: Annual Action Plan 2013-14 2.1 Program review of AAP 2013-14 ……………………………………………………………… 32 2.2 Financial progress in 2013-14 ……………………………………………………………………………. 36 Section 3: Annual Action Plan (AAP) 2014-15 3.1 AAP 2014-15- Programmatic Plan …………………………………………………… 37 3.2 AAP 2014-15 - Detailed activities …………………………………………………… 41 3.3 Requirement of funds ………………………………………………………………………. 66 Section 4: Annexures 4.1 Contact details of DSWOs …………………………………………………………………….. 67 4.2 Copy of various Orders / Letters issued the state govt. …………………………… 68 – 75 4.3 Brief design of various Pilots proposed …………………………………………………. 76 – 90 4.4 Procurement plan for Goods and Services ……………………………………………. 91 4.5 Detailed budget -

STATE NAME DISTRICT NAME GP Village CSP Name Contact Number Model Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Guthulavari Palem DURGA

STATE_NAME DISTRICT NAME GP Village CSP Name Contact number Model Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Guthulavari Palem DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Nemam Nemam DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Panduru Panduru DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Minorpeta DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Parrakalva DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Suryarao Peta Suryarao Peta DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT Andhra Pradesh East Godavari Thimmapuram Thimmapuram DURGA BHAVANI BODDU 9948770342 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek GADHI BESHAK asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek NAGLA PAR asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek NAGLAR asif ali 9991586053 EBT HARYANA PANIPAT gadhi beshek RAGA MAJRA asif ali 9991586053 EBT JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA Opa Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA JARIO Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI JHARKHAND LOHARDAGA OPA ROCHO Kartik Ramsahay bhagat 8102148415 FI HARYANA BHIWANI VPOKAKROLI HUKMI Badhra KULWANT SINGH 8059809736 EBT HARYANA BHIWANI VPOKAKROLI HUKMI GOPI(35) KULWANT SINGH 8059809736 EBT MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON SEEGON ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON HANDIA ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA SEEGON DHEDIYA ASHOK DHANGAR 9753460362 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA RAMTEKRAYYAT RAMTEK RAIYAT JAGDISH KALME 8120828495 PMJDY MADHYA PRADESH HARDA RAMTEKRAYYAT