“The Song of Selling Olives”: Acoustic Experience and Cantonese Identity in Canton, Hong Kong, and Macau Across the Great Divide of 1949

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media

China Perspectives 2018/3 | 2018 Twenty Years After: Hong Kong's Changes and Challenges under China's Rule Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media Francis L. F. Lee Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.8009 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2018 Number of pages: 9-18 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Francis L. F. Lee, “Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media”, China Perspectives [Online], 2018/3 | 2018, Online since 01 September 2018, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 8009 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media FRANCIS L. F. LEE ABSTRACT: Most observers argued that press freedom in Hong Kong has been declining continually over the past 15 years. This article examines the problem of press freedom from the perspective of the political economy of the media. According to conventional understanding, the Chinese government has exerted indirect influence over the Hong Kong media through co-opting media owners, most of whom were entrepreneurs with ample business interests in the mainland. At the same time, there were internal tensions within the political economic system. The latter opened up a space of resistance for media practitioners and thus helped the media system as a whole to maintain a degree of relative autonomy from the power centre. However, into the 2010s, the media landscape has undergone several significant changes, especially the worsening media business environment and the growth of digital media technologies. -

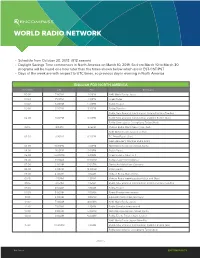

World Radio Network

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

07Cmyblookinside.Pdf

2007 China Media Yearbook & Directory WELCOMING MESSAGE ongratulations on your purchase of the CMM- foreign policy goal of China’s media regulators is to I 2007 China Media Yearbook & Directory, export Chinese culture via TV and radio shows, films, Cthe most comprehensive English resource for books and other cultural products. But, of equal im- businesses active in the world’s fastest growing, and portance, is the active regulation and limitation of for- most complicated, market. eign media influence inside China. The 2007 edition features the same triple volume com- Although the door is now firmly shut on the establish- bination of CMM-I independent analysis of major de- ment of Sino-foreign joint venture TV production com- velopments, authoritative industrial trend data and panies, foreign content players are finding many other fully updated profiles of China’s major media players, opportunities to actively engage with the market. but the market described has once again shifted fun- damentally on the inside over the last year. Of prime importance is the run-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympiad. At no other time in Chinese history have so Most basically, the Chinese economic miracle contin- many foreign media organizations engaged in co- ued with GDP growth topping 10 percent over 2005-06 production features exploring the modern as well as and, once again, parts of China’s huge and diverse old China. But while China has relaxed its reporting media industry continued to expand even faster over procedures for the duration, it would be naïve to be- the last twelve months. lieve this signals any kind of fundamental change in the government’s position. -

Chinese, US Textile Companies Share Worldview

Tuesday, July 18, 2017 CHINA DAILY USA 2 ACROSS AMERICA Chinese, US textile companies share worldview By AMY HE in New York the center of textile and appar- clients are taking interest in our [email protected] el production in China, have designs — the newer, trendier their own exhibition area at the and unique designs,” he said. The Chinese and American Javits Center. Zhou said that the industry textile industries are collaborat- “Today, China is the US’ larg- is a tough one to work in now, ing more closely than ever as est trading partner—our bilat- as it recovers from a worldwide the US becomes a “key player eral trade, bilateral investment, slump the past few years. in the international strategy” of and people-to-people exchanges “We work with smaller China’s textile companies, said have all reached historic highs, brands now, collaborating with Xu Yingxin, vice-president of and in this connection, I think them directly, like with Jones the China National Textile and the textile industry has made big New York and Andrew Marc. Apparel Council. contributions to this growth,” The clients may order less prod- “The United States is not just said Zhang Qiyue, Chinese con- uct, but the prices of the pieces a key trading partner with Chi- sul general in New York. are higher, and so we’re earning na in the textile industry; it is “The textile cooperation has more profi t,” he said. also a key player in the interna- not just brought tangible ben- China Textiles Development tional strategy of China’s textile efi ts to our two peoples, it has Center, based in Beijing, is a industry,” Xu said on Monday also contributed to global eco- new participant to the textile at the opening ceremony of nomic growth,” she said. -

Textual Research for Latin Names and Medicinal Effects of Low Grade Drugs in Shennongbencaojing

J Chin Med 24(1): 65-84, 2013 65 TEXTUAL RESEARCH FOR LATIN NAMES AND MEDICINAL EFFECTS OF LOW GRADE DRUGS IN SHENNONGBENCAOJING Shu-Ling Liu*, Chao-Lin Kuo, Yu-Jen Ko, Ming-Tsuen Hsieh Department of Chinese Pharmaceutical Sciences and Chinese Medicine Resources, College of Pharmacy, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan ( Received 11th May 2012, accepted 23th August 2012 ) The textual research for Latin names and medicinal effects of Shennongbencaojing, after Top Grade and Medium Grade, the Low Grade Drugs was studied. The Low Grade Drugs were divided, in the same way for Top and Medium Grade Drugs, into 6 groups and their drugs number were also shown in the following order: Plant (72 drugs), Mineral (7 drugs), Animal (6 drugs), Fish and Shellfish (2 drugs), Insect (14 drugs) and Other (2 drugs). The number of Low Grade Drugs in Sun’s edition was summed up to 103. In this study, many drugs were considered to be toxic such as: Aconitum carmichaeli (No. 1), Pinellia ternata (No. 4), Rheum palmatum (No. 7), Hyoscyamus niger (No. 10), Veratrum nigrum (No. 13), Gelsemium elegans (No. 14), Dichroa febrifuga (No. 17), Euphorbia pekinensis (No. 24), Agrimonia pilosa (No. 29), Rhododendron molle (No. 30), Phytolacca acinosa (No. 31) etc. They were also listed in the Poisonous Weeds Class of Compendium of Materia Medica. Modern research has confirmed that most of the Low Grade Drugs are toxic as well. For four drugs, Guanjun (No. 22), Yangtao (No. 37), Wujiu (No. 41) and Yaoshigen (No. 64) their botanical names have not yet been defined. Some drugs might have different medicinal names by various used parts but were originated in the same scientific name. -

I Want to Be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition

Volume 6 Issue 1 2020 “I Want to be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition Charlene Peishan Chan [email protected] ISSN: 2057-1720 doi: 10.2218/ls.v6i1.2020.4398 This paper is available at: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/lifespansstyles Hosted by The University of Edinburgh Journal Hosting Service: http://journals.ed.ac.uk/ “I Want to be More Hong Kong Than a Hongkonger”: Language Ideologies and the Portrayal of Mainland Chinese in Hong Kong Film During the Transition Charlene Peishan Chan The years leading up to the political handover of Hong Kong to Mainland China surfaced issues regarding national identification and intergroup relations. These issues manifested in Hong Kong films of the time in the form of film characters’ language ideologies. An analysis of six films reveals three themes: (1) the assumption of mutual intelligibility between Cantonese and Putonghua, (2) the importance of English towards one’s Hong Kong identity, and (3) the expectation that Mainland immigrants use Cantonese as their primary language of communication in Hong Kong. The recurrence of these findings indicates their prevalence amongst native Hongkongers, even in a post-handover context. 1 Introduction The handover of Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1997 marked the end of 155 years of British colonial rule. Within this socio-political landscape came questions of identification and intergroup relations, both amongst native Hongkongers and Mainland Chinese (Tong et al. 1999, Brewer 1999). These manifest in the attitudes and ideologies that native Hongkongers have towards the three most widely used languages in Hong Kong: Cantonese, English, and Putonghua (a standard variety of Mandarin promoted in Mainland China by the Government). -

China Media Bulletin

Issue No. 154: May 2021 CHINA MEDIA BULLETIN Headlines ANALYSIS The Gutting of Hong Kong’s Public Broadcaster P2 IN THE NEWS • Regulators “clean up” internet ahead of CCP anniversary alongside censorship of Oscars, Bible apps, and Weibo P5 • Surveillance updates: Personal data-protection law advances, Apple compromises on user data, citizen backlash P6 • Criminal charges for COVID commentary, Uyghur religious expression, Tibetan WeChat use P7 • Hong Kong: Website blocks, netizen arrests, journalist beating, and Phoenix TV ownership change P9 • Beyond China: Beijing’s COVID-19 media strategy, waning propaganda impact in Europe, new US regulations to enhance transparency P10 FEATURED PUSHBACK Netizens demand transparency on Chengdu student’s death P12 WHAT TO WATCH FOR P13 TAKE ACTION P14 IMAGE OF THE MONTH Is RTHK History? This cartoon published on April 5 by a Hong Kong visual arts teacher is part of a series called “Hong Kong Today.” It depicts a fictional Hong Kong Museum of History, which includes among its exhibits two institutions that have been critical to the city’s freedom, but are being undermined by Chinese and Hong Kong government actions. The first is the Basic Law, the mini-constitution guaranteeing freedom of expression and other fundamental rights; the other is Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK), the once-respected public broadcaster now facing a government takeover. The teacher who posted the cartoon is facing disciplinary action from the Education Department. Credit: @vawongsir Instagram Visit http://freedomhou.se/cmb_signup or email [email protected] to subscribe or submit items. CHINA MEDIA BULLETIN: MAY 2021 ANALYSIS The Gutting of Hong Kong’s Public Broadcaster By Sarah Cook A government takeover of Radio Television Hong Kong has far-reaching Sarah Cook is the implications. -

Harvardasia Quarterly

FALL/WINTER 2013, Vol. XV, No. 3/4 HarvardA Journal of Asian StudiesAsia Affiliated with the HarvardQuarterly University Asia Center INSIDE: BEN HAMMER · Textual Scholarship in Ancient Chinese Studies JEONGHOON HA · Why South Korea Ratified the Treaty on the Non- NON ARKARAPRASERTKUL · Traditionalism and Shanghai’s Alleyways Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) in 1975 DAVID HOPKINS · Kessen Musume MICHA’EL tanCHUM · India’s Not-So-Splendid Isolation HELEN MACNAUGhtan · The Life and Legacy of Kasai Masae: SHARINEE JAGTIANI · ASEAN and Regional Security The Mother of Japanese Volleyball NORI KATAGIRI · Great Power Politics: China and the United States SCott MORRISON · Islamic Banking in the Maldives Harvard Asia Quarterly FALL/WINTER 2013, Vol. XV, No. 3/4 EdIToR-IN-chIEF Alissa Murray MANAgINg EdIToR Jing Qian dEPuTy EdIToR-IN-chIEF Rachel Leng AREA EDITORS chINA AREA head Editor: Justin Thomas Xiaoqian hu Shuyuan Jiang JAPAN AREA head Editor: danica Truscott Kevin Luo hannah Shepherd KOREA AREA head Editor: Keungyoon Bae Rachel Leng Xiao Wen SOUThEAST ASIA AREA head Editor: Soobin Kim Purachate Manussiripen ching-yin Kwan SOUTh ASIA AREA head Editor: yukti choudhary Gerard Jumamil Wishuporn Shompoo The Harvard Asia Quarterly is a journal of Asian studies affiliated with the harvard university Asia center. ABouT ThE harvard uNIVERSITy ASIA cENTER Established on July 1, 1997, the harvard university Asia center was founded as a university-wide interfaculty initiative with an underlying mission to engage people across disciplines and regions. It was also charged with expanding South and Southeast Asian studies, including Thai Studies, in the university’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. -

Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism

Emory International Law Review Volume 35 Issue 1 2021 Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism Shucheng Wang Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Shucheng Wang, Hong Kong's Civil Disobedience Under China's Authoritarianism, 35 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 21 (2021). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol35/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WANG_2.9.21 2/10/2021 1:03 PM HONG KONG’S CIVIL DISOBEDIENCE UNDER CHINA’S AUTHORITARIANISM Shucheng Wang∗ ABSTRACT Acts of civil disobedience have significantly impacted Hong Kong’s liberal constitutional order, existing as it does under China’s authoritarian governance. Existing theories of civil disobedience have primarily paid attention to the situations of liberal democracies but find it difficult to explain the unique case of the semi-democracy of Hong Kong. Based on a descriptive analysis of the practice of civil disobedience in Hong Kong, taking the Occupy Central Movement (OCM) of 2014 and the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (Anti-ELAB) movement of 2019 as examples, this Article explores the extent to which and how civil disobedience can be justified in Hong Kong’s rule of law- based order under China’s authoritarian system, and further aims to develop a conditional theory of civil disobedience for Hong Kong that goes beyond traditional liberal accounts. -

Guo Degang: a Xiangsheng

Shenshen Cai Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne Guo Degang A Xiangsheng (Cross Talk) Performer Bridging the Gap Between Su (Vulgarity) and Ya (Elegance) Xiangsheng 相声 (cross talk), which has been one of the most popular folk art performance genres with the Chinese people since its emergence during the Qing Dynasty, began to lose its popularity at the turn of the 1990s. How- ever, this downward trajectory changed from about 2005, and it once again began to enthuse the public. The catalyst for this change in fortune has been attributed to Guo Degang and his Deyun Club 德云社. The general audience acclaim for Guo Degang’s xiangsheng performance not only turned him into a xiangsheng master and a grassroots cultural hero, it also, somewhat absurdly, evoked criticism from a few critics. The main causes of the negative critiques are the mundane themes and the ubiquitous vulgar baofu 包袱 (comical ele- ments) and rude jokes enlisted in Guo’s xiangsheng performance that revolve around the subjects of ethics, pornography, and prostitution, and which turn Guo into a signifier of vulgarity. However, with the media platform provided via the Weibo 微博 microblog, Guo Degang demonstrates his penchant for refined taste and his talent as an elegant literati. Through an in-depth analy- sis of both Guo Degang’s xiangsheng performance and his microblog entries, this paper will examine the contrasting features between Guo Degang’s artis- tic creations and his “private” life. Also, through the opposing contents and reflections of Guo Degang’s xiangsheng works and his microblog writings, an opaque and sometimes diametrically opposed insight into his worldviews is provided, and a glimpse of the dualistic nature of engagement and withdrawal from the world is revealed. -

The “Lyrical” Expression of History: the Relationship Between History and Lyricism in the Yangzhou Play “Long Canal Willow”

The “Lyrical” Expression of History: The Relationship between History and Lyricism in the Yangzhou Play “Long Canal Willow” Zijun LIU Yangzhou Institute of Quyi Abstract: The lyric expression of history, both ancient and modern Chinese and foreign literary works have dabble in, but there is no unified theory, the author tries to introduce this concept, to the creation, performance play a certain role of inspiration. If history cannot be expressed in a lyrical way, then the temperature of history cannot be felt by ordinary people. The dissemination of historical ideas is finally rooted in the people's minds from the perspective of ordinary people. It is also a clever combination of art and history. Youyou Yunyun Willow is a representative work of Yangzhou Tanchi, which expresses the canal culture of Yangzhou. This paper will try to analyze the success of Youyou Yunyun Willow from the lyric expression of history. Keywords: History; Lyric expression; Tanci DOI:10.47297/ wsprolaadWSP2634-786503.20200104 angzhou Tanci, formerly known as Xianci, is a kind of play lyric song system based Yon Yangzhou dialect. It is mainly based on speaking and supplemented by playing and singing. The representative books include “Double Golden Ingots”, “Pearl Tower”, “Falling Gold Fan”, “Diao Liu’s”, etc. The Yangzhou Tanci and Yangzhou commentary are sister arts, formed in the late Ming Dynasty and flourished in the early Qing Dynasty, with a history of more than 400 years. It originated in Yangzhou and spread in Zhenjiang, Nanjing and the area around the Lixia River in central Jiangsu. “Long Canal Willow” is a representative work of Yangzhou Tanci, which expresses the culture of Yangzhou canal. -

Introduction

introduction The disembodied voices of bygone songstresses course through the soundscapes of many recent Chinese films that evoke the cultural past. In a mode of retro- spection, these films pay tribute to a figure who, although rarely encountered today, once loomed large in the visual and acoustic spaces of popu lar music and cinema. The audience is invited to remember the familiar voices and tunes that circulated in these erstwhile spaces. For instance, in a film by the Hong Kong director Wong Kar- wai set in the 1960s, In the Mood for Love, a traveling businessman dedicates a song on the radio to his wife on her birthday.1 Along with the wife we listen to “Hua yang de nianhua” (“The Blooming Years”), crooned by Zhou Xuan, one of China’s most beloved singers of pop music. The song was originally featured in a Hong Kong production of 1947, All- Consuming Love, which cast Zhou in the role of a self- sacrificing songstress.2 Set in Shang- hai during the years of the Japa nese occupation, the story of All- Consuming Love centers on the plight of Zhou’s character, who is forced to obtain a job as a nightclub singer to support herself and her enfeebled mother-in- law after her husband leaves home to join the resis tance. “The Blooming Years” refers to these recent politi cal events in a tone of wistful regret, expressing the home- sickness of the exile who yearns for the best years of her life: “Suddenly this orphan island is overshadowed by miseries and sorrows, miseries and sorrows; ah, my lovely country, when can I run into your arms again?”3