Book Review: British Generals in Blair's Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transitions in Iraq: Changing Environment Changing Organizations Changing Leadership

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE COMMANDER U.S. JOINT FORCES COMMAND 1562 MITSCHER AVENUE SUITE 200 IN REPLY REFER TO: NORFOLK, VA 23551-2488 102 20 JAN 2010 Mr. Steven Aftergood Federation of American Scientists 1725 DeSales Street NW, 6th Floor Washington, DC 20036 Dear Mr. Aftergood, This is a partial response to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, dated 7 May 2008, in which you seek a copy of a 2006 study of operations in Iraq that was performed by the Joint Warfighting Center at the direction of the Joint Chiefs and the Secretary of Defense. U.S. Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM) conducted a thorough search and discovered one hundred eighty-seven (187) pages of documents responsive to your request. We are releasing a partial copy of this information: portions of pages 47-51 are being withheld under Exemption 1; portions of pages 140-141 are being withheld under Exemption 2; and portions of pages 17-22 and 140 are being withheld under Exemption 6. Exemption 1 pertains to information specifically authorized by an Executive order to be kept secret in the interest of national defense or foreign policy that is properly classified pursuant to such Executive order. Exemption 2 pertains to internal information the release of which would constitute a risk of circumvention of a legal requirement. Exemption 6 pertains to information the release of which would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of the personal privacy of a third party. Please be advised that this is only a partial response. Significant portions of this record fall under the jurisdiction of other agencies, whom USJFCOM must consult regarding their equities. -

IRAQ.Race Against the Clock.11-06-03

MIDDLE EAST Briefing Baghdad/Amman/Brussels, 11 June 2003 BAGHDAD: A RACE AGAINST THE CLOCK I. OVERVIEW to war have all complicated the task facing the new rulers, but Saddam’s fall has already brought some immensely positive changes. For the first time in a Eight weeks after victoriously entering Baghdad, generation, Iraqis can express themselves without American forces are in a race against the clock. If fear. Not surprisingly, they have begun exercising they are unable to restore both personal security their newly gained liberties, including via protest and public services and establish a better rapport marches against some of the policies of the very with Iraqis before the blistering heat of summer forces that made such manifestations of discontent sets in, there is a genuine risk that serious trouble possible in the first place. They have started to will break out. That would make it difficult for elect, or select, new leaderships in ministries, genuine political reforms to take hold, and the national institutions, municipal councils and political liberation from the Saddam Hussein professional associations. These are rudimentary dictatorship would then become for a majority of forms of participatory democracy that, if sustained, the country’s citizens a true foreign occupation. hold promise of yielding a new legitimate national With all eyes in the Middle East focused on Iraq, leadership and laying the foundation for a vibrant the coming weeks and months will be critical for open society. shaping regional perceptions of the U.S. as well. Yet ICG found Baghdad a city in distress, chaos and Ordinary Iraqis, political activists, international aid ferment. -

Section 10.1 Reconstruction

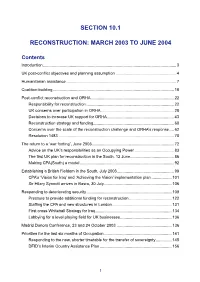

SECTION 10.1 RECONSTRUCTION: MARCH 2003 TO JUNE 2004 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 UK post-conflict objectives and planning assumption ...................................................... 4 Humanitarian assistance .................................................................................................. 7 Coalition-building ............................................................................................................ 18 Post-conflict reconstruction and ORHA .......................................................................... 22 Responsibility for reconstruction .............................................................................. 22 UK concerns over participation in ORHA ................................................................. 28 Decisions to increase UK support for ORHA ............................................................ 43 Reconstruction strategy and funding ........................................................................ 60 Concerns over the scale of the reconstruction challenge and ORHA’s response .... 62 Resolution 1483 ....................................................................................................... 70 The return to a ‘war footing’, June 2003 ......................................................................... 72 Advice on the UK’s responsibilities as an Occupying Power ................................... 83 The first UK plan -

Notes on Contributors

Review of International Studies (2009), 35, 723–728 Copyright British International Studies Association doi:10.1017/S0260210509990441 . NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS Richard J. Aldrich is Professor of International Security at the Warwick University https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms and is the author of several books including The Hidden Hand: Britain American and Cold War Secret Intelligence (John Murray Publishers Ltd, 2001) which won the Donner Book prize in 2002. He is currently directing the AHRC project, ‘Landscapes of Secrecy: The Central Intelligence Agency and the contested record of US foreign policy, 1947–2001’. He has held a Fulbright fellowship at Georgetown University and more recently has spent time in Canberra and Ottawa as a Leverhulme Fellow. Tarak Barkawi is Senior Lecturer in war studies at the Centre of International Studies, University of Cambridge. He specialises in the study of war, armed forces and society with a focus on conflict between the West and the global South. He earned his doctorate at the University of Minnesota. His publications include Globalization and War (Rowman and Littlefield, 2005); ‘Peoples, Homelands and , subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at Wars? Ethnicity, the Military and Battle among British Imperial Forces in the War against Japan’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 46:1 (January 2004); ‘Strategy as a Vocation: Weber, Morgenthau and Modern Strategic Studies’, Review of International Studies, 24:2 (1998); and with Mark Laffey, ‘The Imperial Peace: Democracy, Force, and Globalization’, European Journal of International Relations, 5:4 (1999) and ‘The Postcolonial Moment in Security Studies’, Review of 25 Sep 2021 at 18:00:22 International Studies, 32:4 (2006). -

Soldiers at 16: Sifting Fact from Fiction

SOLDIERS AT SIFTING16: FACT FROM FICTION SOLDIERS AT 16: SIFTING FACT FROM FICTION ‘The fact that the British Fewer than 20 countries worldwide still armed forces continue allow their armed forces to recruit young to recruit from the age of people from age 16. The UK is among 16 sets a poor example them; it is the only major military power internationally and impedes and the only European state to recruit global efforts to end the from such a young age.1 use of child soldiers. The Army surely does not need Across British society – from children’s to make youngsters sign up organisations to veterans to parliamentary formally at such a young committees – this policy is now being challenged. age – there have to be Most of the public agree that change is due – only other, better ways to meet one in seven thinks that 16 is an acceptable age to our requirements whilst train as a soldier.2 respecting our human rights obligations.’4 Despite this widespread unease, a number of common misconceptions still lead many 16 and 17 year olds to leave their education early and enlist. Major General (retd) Here, we examine these ‘myths’ in light of the Tim Cross CBE evidence available.3 ‘Doesn’t the army give young people 1. great education and training?’ The army is exempt from the law that requires all young people aged 16 and 17 to participate in a minimum amount of education each year.5 This means that the army’s standards of education participation are lower than those that apply to young civilians. -

News Media Coverage of the Iraq War in Basra, Fall 2007: a Case Study in “Spinning” News for the State

International Journal of Communication 2 (2008), 976-992 1932-8036/20080976 News Media Coverage of the Iraq War in Basra, Fall 2007: A case study in “spinning” news for the state KURT LANCASTER Northern Arizona University “When we're dealing with Iraq, there's no amount of spin from Washington, or from the U.S. military, or from anyone else that actually matters — [their spin only] helps us feel well, feel good about what's going on in Iraq.” — Scott Peterson, The Christian Science Monitor By examining several mainstream press stories from The New York Times, CNN.com and the Associated Press during the fall of 2007, the author argues how mainstream news media have mostly failed to examine and put into headlines one of the devastating side effects of the occupation of Iraq: armed militias exerting harsh conditions on the citizens of Iraq, especially in the city of Basra, the site of one of the largest untapped oil reserves in the world. This failure stems from the fact that most of the media appear compliant and complicit in adhering to the government’s presentation of conditions in Basra − that it appears to be improving under “regime change.” News sources not beholden to this influence, the alternative news sites of Salon.com, The Christian Science Monitor, BBC News, and Juan Cole’s Informed Comment blog published stories challenging the views presented by the state, sourcing news outside official government channels. By doing so, readers find that the rise of armed militias in Basra caused corruption in the election process, resulting in a stagnation and decay of Basra’s infrastructure, the loss of jobs, and the rise of Taliban-like religious edicts taking away women’s freedom, as well as music from the public places of the city, which was once considered the Venice of the East. -

The Cornwallis Group Xiv: Analysis for Societal Conflict and Counter-Insurgency

THE CORNWALLIS GROUP XIV: ANALYSIS FOR SOCIETAL CONFLICT AND COUNTER-INSURGENCY 2 THE CORNWALLIS GROUP XIV: ANALYSIS OF SOCIETAL CONFLICT AND COUNTER-INSURGENCY WOODCOCK: INTRODUCTION TO CORNWALLIS XIV 3 Introduction to Cornwallis XIV: Analysis of Societal Conflict and Counter-Insurgency Alexander E. R. Woodcock, Ph. D. Chair, The Cornwallis Group and Scolopax International Consultants Burke, Virginia, U.S.A. e-mail: [email protected] Alexander (Ted) Woodcock is Chair and Proceedings Editor of the Cornwallis Group. He is a private consultant and has worked for several US government entities. He is an Affiliate Professor at George Mason University (GMU) School of Public Policy. Dr. Woodcock is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine in London and a Foreign Member of the Royal Swedish Academy of War Sciences. He was a Senior Research Professor and Director of the Societal Dynamics Research Center at George Mason University School of Public Policy. Previously he was Chief Scientist and Vice President at BAE SYSTEMS-Portal Solutions (formerly Synectics Corporation), Fairfax, Virginia. Woodcock is also a Guest Professor at the National Defence College, Stockholm, Sweden, and was a Visiting Professor at the Royal Military College of Science, Shrivenham, England for 10 years. He is actively involved in the development and implementation of societal dynamics models of military, political, economic, and other processes for the modeling and analysis of low intensity conflict, peace and humanitarian operations, and related areas. Woodcock was Project Director for the Strategic Management System (STRATMAS®) project that produced a facility that uses genetic algorithms and intelligent automata methods for the definition and optimal deployment of civilian and military entities in peace and humanitarian operations. -

Agenda and Papers for 1 February 2018 Board Meeting

Board Meeting Thursday 1 February 2018 Venue: S3.41 (New Boardroom), 3rd floor, Seacole building, 2 Marsham Street, SW1P 4DF Board breakfast 9.00am 75 mins Water Resources pre Stakeholder event Harvey Bradshaw 10.15am informative session with Peter Simpson CEO of 75 mins Anglian Water 1. Apologies Emma Howard Boyd 11.30am 2. Declarations of Interest Emma Howard Boyd 5 mins 3. Minutes of the Board meeting held on 5 Emma Howard Boyd December 2017 and matters arising 4. Topical Update items 4.1 Chief Executive’s update James Bevan 11.35am 4.2 25 Year Environment Plan and EU Exit Harvey Bradshaw 40 mins 5. Committee meetings – oral updates and forward 12.15pm look 20 mins 5.1 Pensions Joanne Segars 5.2 E&B including annual review Gill Weeks 5.3 FCRM Lynne Frostick 5.4 Audit and Risk Assurance including annual Gill Weeks (for review Karen Burrows) 6. Regular update items 6.1 Schemes of Delegation (for approval) Joanne Segars 12.35pm 6.2 Finance report (for information) Bob Branson 10 mins Lunch 12.45pm 30 mins 7. Defra head of function guests – Jac Broughton, Emma Howard Boyd 1.15pm HR Head of Function for the Defra Group and 60 mins John Seglias, DDTS Head of Function for the Defra Group Break 2.15pm 10 mins 8. FCRM GiA final indicative allocation for 2018/19 John Curtin 2.25pm (for approval) 20 mins 9. Charges items 9.1 Levies and Charges (for approval) Bob Branson 9.2 Strategic Review of Charges (for Harvey Bradshaw 2.45pm information) 45 mins 9.3 Mobilising More Money Harvey Bradshaw 10. -

General Tim Cross CBE Visiting Professor University of Reading Department of Politics & International Relations

General Tim Cross CBE Visiting Professor University of Reading Department of Politics & International Relations Major General (Retired) Tim Cross CBE was commissioned into the British Army in 1971. He commanded at every level, from leading a small Bomb Disposal Team in Northern Ireland in the 1970’s to commanding a Division of 30,000 in 2004/07. He completed a tour with the UN in Cyprus in 1980/81 before attending the Army Staff Course in 1983, returning as a member of the teaching staff in 1987. After an operational deployment to Kuwait/Iraq in 1990/91, he attended the Higher Command and Staff Course in early 1995 before serving as a Colonel in Bosnia in 1995/96 and 1997. In 1999, as a Brigadier in command of 101 Logistic Brigade, he deployed to Macedonia, Albania and Kosovo and was appointed CBE in the subsequent operational awards for his work in leading the NATO response to the Humanitarian crisis. Handing over command in 2000 he attended the Royal College of Defence Studies and then, in 2002, he became involved in the planning for operations in Iraq; he subsequently deployed to Washington, Kuwait and Baghdad as the Deputy in the US-led Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Affairs, later re-titled the CPA (the Coalition Provisional Authority). Returning to the UK in 2003, he took over a key staff appointment before assuming command of one of the three Divisions of the UK Field Army from October 2004 to November 2007. On retirement in 2007 he developed a portfolio of activities, including becoming the Army Adviser to the UK House of Commons Defence Committee until 2012. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-04785-3 - The Direction of War: Contemporary Strategy in Historical Perspective Hew Strachan Frontmatter More information The Direction of War The wars since 9/11, in both Iraq and Afghanistan, have generated frustra- tion and an increasing sense of failure in the west. Much of the blame has been attributed to poor strategy. In both the United States and the United Kingdom, public enquiries and defence think tanks have detected a lack of consistent direction, of effective communication and of governmental coordination. In this important new book, Sir Hew Strachan, one of the world’s leading military historians, reveals how these failures resulted from a fundamental misreading and misapplication of strategy itself. He argues that the wars since 2001 have not in reality been as ‘new’ as has been widely assumed and that we need to adopt a more historical approach to contemporary strategy in order to identify what is really changing in how we wage war. If war is to fulfil the aims of policy, then we need first to under- stand war. Hew Strachan is Chichele Professor of the History of War at the University of Oxford and a Fellow of All Souls College. Between 2004 and 2012 he was the Director of the Oxford Programme on the Changing Character of War. He also serves on the Strategic Advisory Panel of the Chief of the Defence Staff, on the UK Defence Academy Advisory Board, and on the Council of the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Foreign Policy listed him as one of the most influential global thinkers for 2012 and he was knighted in the New Year’s Honours for 2013. -

BBC Documentary

BBC Documentary: No Plan, No Peace GB165-0429 Reference code: GB165-0429 Title: BBC Documentary: ‘No Plan, No Peace’ Collection Name of creator: British Broadcasting Corporation Dates of creation of material: 2007 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 3 boxes Administrative history: The two part documentary ‘No Plan, No Peace: The inside story of Iraq’s descent into chaos’ was produced by BBC Current Affairs and broadcast on the 28th and 29th October 2007. Scope and content: Scripts for the two part BBC documentary ‘No Plan, No Peace: The inside story of Iraq’s descent into chaos’ and transcripts of research interviews for the documentary of key participants including Ahmed Chalabi, Ali Allawi, Barbara Bodine, Sir Christopher Meyer, Clare Short, General Jay Garner, Colonel Larry Wilkerson, Paul Bremer, Colonel Paul Hughes, Sir Jeremy Greenstock, Sir Michael Jackson, Stewart Bowen and Major General Tim Cross. System of arrangement: 1 Script of Documentary 2 Research Interviews Access conditions: Open Language of material: English Conditions governing reproduction: No restrictions on copying or quotation other than statutory regulations and preservation concerns. Any quotation must credit the BBC and the Documentary ‘No Plan, No Peace’. Immediate source of acquisition: Received as a gift from Michael Rudin (producer BBC Current Affairs) on 19 Jun 2008 Finding aids: In Guide; Handlist Archivist’s note: Fonds, series and item level description created by D. Usher 26 Jun 2008 1 ©Middle East Centre, St Antony’s College, Oxford. OX2 6JF BBC Documentary: -

Annual Report Pdf 3.60MB

Ultra Annual Report and Accounts 2019 We are investigators, problem solvers, brilliant thinkers, relentless explorers. We are Ultra. Annual Report and Accounts 2019 OUR TOP CUSTOMERS We work with the US Department of Defense (DoD), the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) and other aerospace, defence and critical infrastructure providers both directly and through prime contractors. Our top 10 contracts accounted for 14% of our 2019 revenue and our top 10 platforms accounted for 19% of revenue. US DoD 22% UK MoD 7% Lockheed Martin 6% Boeing 5% BAE Systems 5% Northrop Grumman 3% Pratt and Whitney 3% General Dynamics 2% US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives 2% Thales 2% Ultra at a glance p8 Our target markets p24 Ultra Annual Report Strategic report Governance Financial statements and Accounts 2019 1 OUR MISSION AND THE REASON WE EXIST Innovating today for a safer tomorrow. OUR OUR GLOBAL MARKETS REACH We operate mainly as a Tier 3 (sub-system) Our core markets are the ‘five-eyes’ nations: and occasionally a Tier 2 systems provider Australia, Canada, New Zealand, UK and USA. in the maritime, C4ISTAR-EW (command, This gives us access to the largest and most control, communications, computers, sophisticated addressable defence budgets intelligence, surveillance, acquisition and in the world. reconnaissance – electronic warfare), military and commercial aerospace, North America 61% nuclear, and industrial sensors markets. UK 21% Maritime 43% Rest of the World 11% Intelligence & Communications 27% Mainland Europe 7% Other critical detection and control markets 30% We provide innovative, mission-specific, bespoke technological solutions to our customers’ most complex problems.