Civil War in Hazarajat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fråga-Svar Afghanistan. Resväg Mellan Kabul Och Ghazni

2015-09-03 Fråga-svar Afghanistan. Resväg mellan Kabul och Ghazni Fråga - Går det flyg mellan Kabul och Ghazni? - Är resvägen mellan Kabul och Ghazni säker för hazarer? - Finns det några organisationer i landet som kan bistå andra med t.ex. eskort för att göra resan säker? - Hur kan underåriga ta sig fram? Svar Nedan följer en sammanställning av information från olika källor. Sammanställningen gör inte anspråk på att vara uttömmande. Refererade dokument bör alltid läsas i sitt sammanhang. Vad gäller säkra resvägar så kan läget snabbt förändras. Vad som gällde då nedanstående dokument skrevs gäller kanske inte idag! Austalia Refugee Review Tribunal (May 2015): Domen handlar om en hazar från Ghazni som under lång tid levt som flykting i Iran. Underlaget till beslutet beskriver situationen angående resvägar i Afghanistan speciellt i provinsen Ghazni. Se utdrag nedan: 33. DFAT’s 2014 Report statcontains the following in relation to road security in Afghanistan: Insecurity compounds the poor condition of Afghanistan’s limited road network, particularly those roads that pass through areas contested by insurgents. Taliban and criminal elements target the national highway and secondary roads, setting up arbitrary armed checkpoints. Sida 1 av 8 Official ANP and ANA checkpoints designed to secure the road are sometimes operated by poorly-trained officers known to use violence to extort bribes. More broadly, criminals and insurgents on roads target all ethnic groups, sometimes including kidnapping for ransom. It is often difficult to separate criminality (such as extortion) from insurgent activity. Individuals working for, supporting or associated with the Government and the international community are at high risk of violence perpetrated by insurgents on roads in Afghanistan. -

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

Role of English in Afghan Language Policy Planning with Its Impact on National Integration (2001-2010)

ROLE OF ENGLISH IN AFGHAN LANGUAGE POLICY PLANNING WITH ITS IMPACT ON NATIONAL INTEGRATION (2001-2010) By AYAZ AHMAD Area Study Centre (Russia, China & Central Asia) UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR (DECEMBER 2016) ROLE OF ENGLISH IN AFGHAN LANGUAGE POLICY PLANNING WITH ITS IMPACT ON NATIONAL INTEGRATION (2001-2010) By AYAZ AHMAD A dissertation submitted to the University of Peshawar in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (DECEMBER 2016) i AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I, Mr. Ayaz Ahmad hereby state that my PhD thesis titled “Role of English in Afghan Language Policy Planning with its Impact on National Integration (2001-2010)” is my own work and has not been submitted previously by me for taking any degree from this University of Peshawar or anywhere else in the country/world. At any time if my statement is found to be incorrect even after my graduation the University has the right to withdraw my PhD degree. AYAZ AHMAD Date: December 2016 ii PLAGIARISM UNDERTAKING I solemnly declare that research work presented in the thesis titled “Role of English in Afghan Language Policy Planning with its Impact on National Integration (2001-2010)” is solely my research work with no significant contribution from any other person. Small contribution/help wherever taken has been duly acknowledged and that complete thesis has been written by me. I understand the zero tolerance policy of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) and University of Peshawar towards plagiarism. Therefore I as an Author of the above-titled thesis declare that no portion of my thesis has been plagiarized and any material used as a reference is properly referred/cited. -

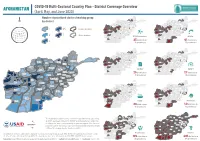

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of Prioritized Clusters/Working Group

AFGHANISTAN COVID-19 Multi-Sectoral Country Plan - District Coverage Overview (April, May, and June 2020) Number of prioritized clusters/working group Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh N by district Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar 1 4-5 province boundary Logar Logar Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Paktya Paktya Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika 2 7 district boundary Zabul Zabul DTM Prioritized: WASH: Hilmand Hilmand Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz 25 districts in 41 districts in 3 10 provinces 13 provinces Badakhshan Badakhshan Jawzjan Kunduz Jawzjan Kunduz Balkh Balkh Takhar Takhar Faryab Faryab Samangan Samangan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Sar-e-Pul Baghlan Panjsher Nuristan Panjsher Nuristan Badghis Parwan Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Bamyan Kapisa Kunar Laghman Laghman Kabul Kabul Maidan Wardak Maidan Wardak Badakhshan Ghor Nangarhar Ghor Nangarhar Jawzjan Logar Logar Kunduz Hirat Daykundi Hirat Daykundi Balkh Paktya Paktya Takhar Ghazni Khost Ghazni Khost Uruzgan Uruzgan Farah Farah Paktika Paktika Faryab Zabul Zabul Samangan Baghlan Hilmand EiEWG: Hilmand ESNFI: Sar-e-Pul Kandahar Kandahar Nimroz Nimroz Panjsher Nuristan 25 districts in 27 districts in Badghis Parwan Bamyan Kapisa Kunar 10 provinces 12 provinces Laghman Kabul Maidan -

Watershed Atlas Part IV

PART IV 99 DESCRIPTION PART IV OF WATERSHEDS I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED II. AMU DARYA RIVER BASIN III. NORTHERN RIVER BASIN IV. HARIROD-MURGHAB RIVER BASIN V. HILMAND RIVER BASIN VI. KABUL (INDUS) RIVER BASIN VII. NON-DRAINAGE AREAS PICTURE 84 Aerial view of Panjshir Valley in Spring 2003. Parwan, 25 March 2003 100 I. MAP AND STATISTICS BY WATERSHED Part IV of the Watershed Atlas describes the 41 watersheds Graphs 21-32 illustrate the main characteristics on area, popu- defined in Afghanistan, which includes five non-drainage areas lation and landcover of each watershed. Graph 21 shows that (Map 10 and 11). For each watershed, statistics on landcover the Upper Hilmand is the largest watershed in Afghanistan, are presented. These statistics were calculated based on the covering 46,882 sq. km, while the smallest watershed is the FAO 1990/93 landcover maps (Shapefiles), using Arc-View 3.2 Dasht-i Nawur, which covers 1,618 sq. km. Graph 22 shows that software. Graphs on monthly average river discharge curve the largest number of settlements is found in the Upper (long-term average and 1978) are also presented. The data Hilmand watershed. However, Graph 23 shows that the largest source for the hydrological graph is the Hydrological Year Books number of people is found in the Kabul, Sardih wa Ghazni, of the Government of Afghanistan – Ministry of Irrigation, Ghorband wa Panjshir (Shomali plain) and Balkhab watersheds. Water Resources and Environment (MIWRE). The data have Graph 24 shows that the highest population density by far is in been entered by Asian Development Bank and kindly made Kabul watershed, with 276 inhabitants/sq. -

The Taliban Conundrum

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 1, Ver. 2 (January 2017) PP 21-26 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Taliban Conundrum Mudassir Fatah Research Scholar, Department of Political Science, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi-110025 Abstract: - National interests do guide the foreign policy of a nation. A state can go to any extent for fulfilling the same. Same had been reflected in the proxy wars played in Afghanistan. It is these national interests of some states which are responsible for the rise of the Taliban movement. Although there are some internal factors who also played a crucial role while giving birth to the Taliban movement, but these internal circumstances were created so to be the part of the conflict which eventually gave rise to the Taliban movement. The cold war power politics played in the poor and a weak nation like Afghanistan resulted in such a force which is still haunting the millions in the world. Keywords: - Afghanistan, Civil War, Peace, Power Politics, Taliban. I. INTRODUCTION Taliban is the plural of ‘Talib’, which has its origin from Arabic. The literal meaning of Talib is seeking something for one’s own self. The word Talib has been derived from the word ‘Talab’ which means desire. The word Taliban, in Pushto, generally denotes, students studying in Deeni Madaris (religious schools).1 These Deeni Madaris were (mostly) Deobandi schools in Pakistan. II. RISE OF THE TALIBAN MOVEMENT-INTERNAL FACTORS After the Soviet departure, the factor which united all the Mujahedeen groups against the common enemy, no longer existed, which resulted into chaos, looting and finally civil war. -

Produced by the Human Security Centre Lead Author

1 Human Security Centre – Written evidence (AFG0019) Produced by the Human Security Centre Lead Author: Simon Schofield, Senior Fellow, In consultation with Rohullah Yakobi, Associate Fellow 2 1 Table of Contents 2. Executive Summary .............................................................................5 3. What is the Human Security Centre?.....................................................10 4. Geopolitics and National Interests and Agendas......................................11 Islamic Republic of Pakistan ...................................................................11 Historical Context...............................................................................11 Pakistan’s Strategy.............................................................................12 Support for the Taliban .......................................................................13 Afghanistan as a terrorist training camp ................................................16 Role of military aid .............................................................................17 Economic interests .............................................................................19 Conclusion – Pakistan .........................................................................19 Islamic Republic of Iran .........................................................................20 Historical context ...............................................................................20 Iranian Strategy ................................................................................23 -

Hazara Tribe Next Slide Click Dark Blue Boxes to Advance to the Respective Tribe Or Clan

Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Advance to Hazara Tribe next slide Click dark blue boxes to advance to the respective tribe or clan. Hazara Abak / Abaka Besud / Behsud / Basuti Allakah Bolgor Allaudin Bubak Bacha Shadi Chagai Baighazi Chahar Dasta / Urni Baiya / Baiyah Chula Kur Barat Dahla / Dai La Barbari Dai Barka Begal Dai Chopo Beguji / Bai Guji Dai Dehqo / Dehqan Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec. Vol 6; Hazaras Poladi, 37; EE Bacon, P.20-31 Topography, Ethnology, Resources & History of Afghanistan. Part II. Calcutta:, 1871 (p. 628). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Return to Advance to First slide Hazara Tribe next slide Hazara Dai Kundi / Deh Kundi Dayah Dai Mardah / Dahmarda Dayu Dai Mirak Deh Zengi Dai Mirkasha Di Meri / Dai Meri Dai Qozi Di Mirlas / Dai Mirlas Dai Zangi / Deh Zangi Di Nuri / Dai Nuri Daltamur Dinyari /Dinyar Damarda Dosti Darghun Faoladi Dastam Gadi / Gadai Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). Adamec. Vol 6; Hazaras Poladi, 37; EE Bacon, P.20-31 Topography, Ethnology, Resources & History of Afghanistan. Part II. Calcutta:, 1871 (p. 628). Program for Culture & Conflict Studies www.nps.edu/programs/ccs Return to Advance to First slide Hazara Tribe next slide Hazara Gangsu Jaokar Garhi Kadelan Gavi / Gawi Kaghai Ghaznichi Kala Gudar Kala Nao Habash Kalak Hasht Khwaja Kalanzai Ihsanbaka Kalta Jaghatu Kamarda Jaghuri / Jaghori Kara Mali Reference: Courage Services Inc., Tribal Hierarchy & Dictionary of Afghanistan: A Reference Aid for Analysts, (February 2007). -

19 October 2020 "Generated on Refers to the Date on Which the User Accessed the List and Not the Last Date of Substantive Update to the List

Res. 1988 (2011) List The List established and maintained pursuant to Security Council res. 1988 (2011) Generated on: 19 October 2020 "Generated on refers to the date on which the user accessed the list and not the last date of substantive update to the list. Information on the substantive list updates are provided on the Council / Committee’s website." Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found at: https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/ombudsperson (for res. 1267) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/sanctions/delisting (for other Committees) https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/2231/list (for res. 2231) A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. INTERPOL- UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/How-we-work/Notices/View-UN-Notices- Individuals click here TAi.121 Name: 1: AZIZIRAHMAN 2: ABDUL AHAD 3: na 4: na ﻋﺰﯾﺰ اﻟﺮﺣﻤﺎن ﻋﺒﺪ اﻻﺣﺪ :(Name (original script Title: Mr Designation: Third Secretary, Taliban Embassy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates DOB: 1972 POB: Shega District, Kandahar Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: na Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: Afghanistan Passport no: na National identification no: Afghan national identification card (tazkira) number 44323 na Address: na Listed on: 25 Jan. -

Afghanistan Ghazni Province Land Cover

W # AFGHANISTAN E C Sar-e K har Dew#lak A N # GHAZNI PROVINCE Qarah Qowl( 1) I Qarkh Kamarak # # # # # Regak # # Gowshak # # # Qarah Qowl( 2) R V Qada # # # # # # Bandsang # # Dopushta Panqash # # # # # # # Qashkoh Kholaqol # LAND COVER MAP # Faqir an O # Sang Qowl Rahim Dad # # Diktur (1) # Owr Mordah Dahane Barikak D # Barigah # # # Sare Jiska # Baday # # Kheyr Khaneh # Uchak # R # Jandad # # # # # # # # # # Shakhalkhar Zardargin Bumak # # Takhuni # # # # # # # Karez Nazar # Ambolagh # # # # # # Barikak # # Hesar # # # # # Yarum # # # A P # # # # # # Kataqal'a Kormurda # # # # Qeshlaqha Riga Jusha Tar Bulagh # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # Ahangari # # Kuz Foladay # Minqol # # # Syahreg (2) # # # Maqa # Sanginak # # Baghalak # # # # # # # # # Sangband # Orka B aba # Godowl # Nayak # # # Gadagak # # # # Kota Khwab Altan # # Bahram # # # Katar # # # Barik # Qafak # Qargatak # # # # # # Garmak (3) # # # # # # # # # # Ternawa # # # Kadul # # # # Ghwach # K # # Ata # # # Dandab # # # # # Qole Khugan Sewak (2) Sorkh Dival # # # # # # # # Qabzar (2) # # Bandali # Ajar # Shebar # Hajegak # Sawzsang Podina N ## # # Churka # Nala # # # # # # # Qabzar-1 Turgha # Tughni # Warzang Sultani # # # # # # # # # # # # # Ramzi Qureh Now Juy Negah # # # # # # # # Shew Qowl # Syahsangak A # # # # # # # O # Diktur (2) # Kajak # # Mar Bolagh R V # Ajeda # Gola Karizak # # # Navor Sham # # Dahane Yakhshi Kolukh P # # # # AIMS Y Tanakhak Qal'a-i Dasht I Qole Aymad # Kotal Olsenak Mianah Bed # # # # N Tarbolagh Mar qolak Minqolak Sare Bed Sare Kor ya Ta`ina -

LAND RELATIONS in BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 Village Case Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Case Studies Series LAND RELATIONS IN BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 village case study Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit By Liz Alden Wily February 2004 Funding for this study was provided by the European Commission, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and the governments of Sweden and Switzerland. © 2004 The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU). All rights reserved. This case study report was prepared by an independent consultant. The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of AREU. About the Author Liz Alden Wily is an independent political economist specialising in rural property issues and in the promotion of common property rights and devolved systems for land administration in particular. She gained her PhD in the political economy of land tenure in 1988 from the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. Since the 1970s, she has worked for ten third world governments, variously providing research, project design, implementation and policy guidance. Dr. Alden Wily has been closely involved in recent years in the strategic and legal reform of land and forest administration in a number of African states. In 2002 the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit invited Dr. Alden Wily to examine land ownership problems in Afghanistan, and she continues to return to follow up on particular concerns. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation that conducts and facilitates action-oriented research and learning that informs and influences policy and practice. -

LAND RELATIONS in BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 Village Case Study

Case Studies Series LAND RELATIONS IN BAMYAN PROVINCE Findings from a 15 village case study Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit By Liz Alden Wily February 2004 Funding for this study was provided by the European Commission, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and the governments of Sweden and Switzerland. © 2004 The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU). All rights reserved. This case study report was prepared by an independent consultant. The views and opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of AREU. About the Author Liz Alden Wily is an independent political economist specialising in rural property issues and in the promotion of common property rights and devolved systems for land administration in particular. She gained her PhD in the political economy of land tenure in 1988 from the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom. Since the 1970s, she has worked for ten third world governments, variously providing research, project design, implementation and policy guidance. Dr. Alden Wily has been closely involved in recent years in the strategic and legal reform of land and forest administration in a number of African states. In 2002 the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit invited Dr. Alden Wily to examine land ownership problems in Afghanistan, and she continues to return to follow up on particular concerns. About the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) The Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) is an independent research organisation that conducts and facilitates action-oriented research and learning that informs and influences policy and practice. AREU also actively promotes a culture of research and learning by strengthening analytical capacity in Afghanistan and by creating opportunities for analysis, thought and debate.