An Investigation of Possible Reservoirs of Lymphoproliferative Disease Virus of Turkeys in Mississippi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HPSC0011 STS Perspectives on Big Problems Course Syllabus

HPSC0011 STS Perspectives on Big Problems Course Syllabus 2020-21 session | STS Staff, course coordinator Dr Cristiano Turbil | [email protected] Course Information This module introduces students to the uses of STS in solving big problems in the contemporary world. Each year staff from across the spectrum of STS disciplines – History, Philosophy, Sociology and Politics of Science – will come together to teach students how different perspectives can shed light on issues ranging from climate change to nuclear war, private healthcare to plastic pollution. Students have the opportunity to develop research and writing skills, and assessment will consist of a formative and a final essay. Students also keep a research notebook across the course of the module This year’s topic is Artificial Intelligence. Basic course information Moodle Web https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=7420 site: Assessment: Formative assessment and essay Timetable: See online timetable Prerequisites: None Required texts: Readings listed below Course tutor(s): STS Staff, course coordinator Dr Cristiano Turbil Contact: [email protected] | Web: https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=7420 Office location: Online for TERM 1 Schedule UCL Date Topic Activity Wk 1 & 2 20 7 Oct Introduction and discussion of AI See Moodle for details as ‘Big Problem’ (Turbil) 3 21 14 Oct Mindful Hands (Werret) See Moodle for details 4 21 14 Oct Engineering Difference: the Birth See Moodle for details of A.I. and the Abolition Lie (Bulstrode) 5 22 21 Oct Measuring ‘Intelligence’ (Cain & See Moodle for details Turbil) 6 22 21 Oct Artificial consciousness and the See Moodle for details ‘race for supremacy’ in Erewhon’s ‘The Book of the Machines’ (1872) (Cain & Turbil) 7 & 8 23 28 Oct History of machine intelligence in See Moodle for details the twentieth century. -

The BG News October 28, 2004

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-28-2004 The BG News October 28, 2004 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 28, 2004" (2004). BG News (Student Newspaper). 7344. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/7344 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. j^k M V Bowling Green State University THURSDAY October 28, 2004 Country looking forward ^^ 1 111 1 PM SHOWERS toIB MAC tourney; PAGE 9 KII I -i-WHN1 A \ \ \< ) HIGH63 LOW48 www.bgnews.com —U VJ ■■" VOLUME 99 ISSUE 56 Political artwork stolen from FAC Six student posters said she feels discouraged and BUSH KERRY fears that the artwork theft were taken last week may hinder students' chances from Fine Arts Center. TWO FLAVORS OF COLA of entering the contest. "It was disrespectful and a violation of their first amend- By lanell Kingsborough SENIOR REPORTER ment rights," Rusnak said. She feels that taking the If il was any other year, the artwork from the display artwork of students in the was one way of silencing the Intermediate Digital Imaging students' voices. course might have lasted longer "Whether people agreed on the wall than one or two with the student's messages days- BOIH BAO (OR vou or not, that did not give Ehem Six posters disappeared last Graphic Created the right to take matters into week from the Fine Arts Center. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Man on Platform Five by Robert Llewellyn Robert Llewellyn

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Man On Platform Five by Robert Llewellyn Robert Llewellyn. Robert Llewellyn is the actor who portrays Kryten from Series III to Series XII. He has also appeared as the presenter of Scrapheap Challenge which ran from 1998-2010 on Channel 4, the host of the web series Carpool which ran from 2009-2014, and as host of the YouTube channel Fully Charged which started in 2010 and still uploads today. Starring on Red Dwarf. Llewellyn's involvement with Red Dwarf came about as a result of his appearance at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, performing in his comedy, Mammon, Robot Born Of Woman . He was invited to audition for the role of Kryten, by Paul Jackson, before joining the cast for Series III. The story is about a robot who, as he becomes more human, begins to behave increasingly badly. This was seen by Paul Jackson, producer of Red Dwarf , and he was invited to audition for the role of Kryten. Llewellyn joined the cast of Red Dwarf in 1989 at the start of Series III and continued in the role until the end of Series VIII in 1999. His skills as a physical performer encouraged Rob Grant and Doug Naylor to write him additional characters for the series, namely Jim Reaper ("The Last Day"), the Data Doctor ("Back in the Red II"), Human Kryten ("DNA"), Bongo ("Dimension Jump") and Able ("Beyond a Joke"). Llewellyn co- wrote the Red Dwarf Series VII episode "Beyond A Joke" with Doug Naylor. He was also the only British cast member originally to participate in the American version of Red Dwarf , though other actors such as Craig Charles and Chris Barrie were also approached to reprise their roles. -

Resampling Residuals on Phylogenetic Trees: Extended Results Peter J

Resampling Residuals on Phylogenetic Trees: Extended Results Peter J. Waddell1, Ariful Azad2 and Ishita Khan2 [email protected] 1Department of Biological Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47906, U.S.A. 2Department of Computer Science, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47906, U.S.A . In this article the results of Waddell and Azad (2009) are extended. In particular, the geometric percentage mean standard deviation measure of the fit of distances to a phylogenetic tree are adjusted for the number of parameters fitted on the tree. The formulae are also presented in their general form for any weight that is a function of the distance. The cell line gene expression data set of Ross et al. (2000) is reanalyzed. It is shown that ordinary least squares (OLS) is a much better fit to the data than a Neighbor Joining or BME tree. Residual resampling shows that cancer cell lines do indeed fit a tree fairly well and that the tree does have strong internal structure. Simulations show that least squares tree building methods, including OLS, are strong competitors with BME type methods for fitting model data, while real world examples often suggest the same conclusion. “… his ignorance and almost doe-like naivety is keeping his mind receptive to a possible solution.” A quotation from Kryten: Red Dwarf VIII-Cassandra Keywords: Resampled Residual Bootstrap, flexi-Weighted Least Squares Phylogenetic Trees fWLS, Balanced Minimum Evolution BME, Phylogenomics, Gene Expression Tree Waddell, Azad and Khan (2010). Extended Results of Residual Resampling on Trees Page 1 1 Introduction This article updates and extends some of the results in Waddell and Azad (2010). -

The Logicist Manifesto: at Long Last Let Logic-Based Artificial Intelligence Become a Field Unto Itself∗

The Logicist Manifesto: At Long Last Let Logic-Based Artificial Intelligence Become a Field Unto Itself∗ Selmer Bringsjord Rensselaer AI & Reasoning (RAIR) Lab Department of Cognitive Science Department of Computer Science Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) Troy NY 12180 USA [email protected] version 9.18.08 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Background 1 2.1 Logic-Based AI Encapsulated . .1 2.1.1 LAI is Ambitious . .3 2.1.2 LAI is Based on Logical Systems . .4 2.1.3 LAI is a Top-Down Enterprise . .5 2.2 Ignoring the \Strong" vs. \Weak" Distinction . .5 2.3 A Slice in the Day of a Life of a LAI Agent . .6 2.3.1 Knowledge Representation in Elementary Logic . .8 2.3.2 Deductive Reasoning . .8 2.3.3 A Note on Nonmonotonic Reasoning . 12 2.3.4 Beyond Elementary Logical Systems . 13 2.4 Examples of Logic-Based Cognitive Systems . 15 3 Factors Supporting Logicist AI as an Independent Field 15 3.1 History Supports the Divorce . 15 3.2 The Advent of the Web . 16 3.3 The Remarkable Effectiveness of Logic . 16 3.4 Logic Top to Bottom Now Possible . 17 3.5 Learning and Denial . 19 3.6 Logic is an Antidote to \Cheating" in AI . 19 3.7 Logic Our Only Hope Against the Dark AI Future . 21 4 Objections; Rebuttals 22 4.1 \But you are trapped in a fundamental dilemma: your position is either redundant, or false." . 22 4.2 \But you're neglecting probabilistic AI." . 23 4.3 \But we now know that the mind, contra logicists, is continuous, and hence dynamical, not logical, systems are superior." . -

Role of Deficient DNA Mismatch Repair Status In

Coordinating Center, NCCTG: N0147 CTSU: N0147 CALGB: N0147 ECOG: N0147 NCIC CTG: CRC.2 SWOG: N0147 North Central Cancer Treatment Group A Randomized Phase III Trial of Oxaliplatin (OXAL) Plus 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU)/Leucovorin (CF) with or without Cetuximab (C225) after Curative Resection for Patients with Stage III Colon Cancer Intergroup Study Chairs Steven R. Alberts, M.D. (Research Base)* Mayo Foundation 200 First Street, SW Rochester, MN 55905 Phone: (507) 284-1328 Fax: (507) 284-5280 E-mail: [email protected] Statisticians Daniel J. Sargent, Ph.D. Mayo Foundation 200 First Street SW Rochester, MN 55905 E-mail: [email protected] Michelle R. Mahoney, M.S. Fax: (507) 266-2477 Phone: (507) 284-8803 * Investigator having NCI responsibility for this protocol. DCTD Supplied Agent via Clinical Supplies Agreement (CSA): Cetuximab (NSC #714692) (Discontinued as of November 25, 2009) Commercial Supplied for patients pre-randomized following the implementation of Addendum 10: Oxaliplatin Document History (Effective Date) Document History (Effective Date) Activation February 10, 2004 NCCTG Addendum 7 January 4, 2008 NCCTG Update 1 February 10, 2004 NCCTG Addendum 8 May 12, 2008 NCCTG Addendum 1 March 29, 2004 NCCTG Addendum 9 August 18, 2008 NCCTG Addendum 2 September 1, 2004 NCCTG Update 3 August 18, 2008 NCCTG Addendum 3 June 1, 2005 NCCTG Addendum 10 May 8, 2009 NCCTG Addendum 4 June 1, 2005 NCCTG Addendum 11 December 18, 2009 NCCTG Addendum 5 August 1, 2005 NCCTG Addendum 12 September 22, 2010 NCCTG Addendum 6 August 15, 2007 NCCTG Addendum 13 June 1, 2011 NCCTG Update 2 August 15, 2007 NCI Version date: April 21, 2011 N0147 2 Addendum 13 Add As of November 25, 2009, all patient enrollments are complete. -

Filozofické Aspekty Technologií V Komediálním Sci-Fi Seriálu Červený Trpaslík

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Teorie interaktivních médií Dominik Zaplatílek Bakalářská diplomová práce Filozofické aspekty technologií v komediálním sci-fi seriálu Červený trpaslík Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Martin Flašar, Ph.D. 2020 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto práci vypracoval samostatně a použil jsem literárních a dalších pramenů a informací, které cituji a uvádím v seznamu použité literatury a zdrojů informací. V Brně dne ....................................... Dominik Zaplatílek Poděkování Tímto bych chtěl poděkovat panu PhDr. Martinu Flašarovi, Ph.D za odborné vedení této bakalářské práce a podnětné a cenné připomínky, které pomohly usměrnit tuto práci. Obsah Úvod ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1. Seriál Červený trpaslík ................................................................................................................... 6 2. Vyobrazené technologie ............................................................................................................... 7 2.1. Android Kryton ....................................................................................................................... 14 2.1.1. Teologická námitka ........................................................................................................ 15 2.1.2. Argument z vědomí ....................................................................................................... 18 2.1.3. Argument z -

Red Dwarf” - by Lee Russell

Falling in love with “Red Dwarf” - by Lee Russell It was around 2003 or 2004 when I fell in love with the British sci-fi comedy show “Red Dwarf”. I had been somewhat aware of the series when it launched in 1988 but the external model shots looked so unrealistic that I didn’t bother to try it… what a mistake! My epiphany came late one night after a long session of distance-studying for a degree with the Open University. Feeling very tired and just looking for something to relax with before going to bed, I was suddenly confronted with one of the funniest comedy scenes I had ever seen. That scene was in the Season VIII episode ‘Back in the Red, part 2’. I tuned in just at the moment that Rimmer was using a hammer to test the anaesthetic that he’d applied to his nether regions. I didn’t know the character or the back story that had brought him to that moment, but Chris Barrie’s wonderful acting sucked me in – I was laughing out loud and had suddenly become ‘a Dwarfer’. With one exception, I have loved every series of Red Dwarf, and in this blog I’ll be reflecting on what has made me come to love it so much over the 12 series that have been broadcast to date. For anyone was hasn’t seen Red Dwarf (and if you haven’t, get out there and find a copy now – seriously), the story begins with three of the series’ main characters who have either survived, or are descended from, a radiation accident that occurred three million years ago and killed all of the rest of the crew of the Jupiter Mining Corp ship ‘Red Dwarf’. -

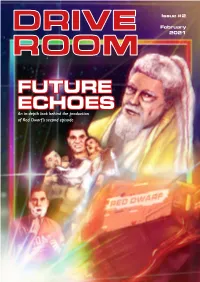

Drive Room Issue 2

Issue #2 February 2021 FUTURE ECHOES An in-depth look behind the production of Red Dwarf’s second episode Contents LEVEL 159 2 Editorial NIVELO 3 Synopsis Well, there was quite a lot to look at for the first ever episode 5 Crew & Other Info of a show, who knew? So this issue will be a little more brief 6 Guest Stars I suspect, a bit leaner, a bit more ‘Green Beret’... but hopefully still a good informative read. 7 Behind The Scenes 11 Adaptations/Other Media My first experience of ‘Future Echoes’ was via the comic-book 14 Character Spotlight version printed in the Red Dwarf Smegazines, and the version 23 Robot Claws used in the Red Dwarf novel. The TV version has therefore 29 always held a bit of a wierd place in my love of the show - as Actor Spotlight much as I can recite it line for line, I’m forever comparing it to 31 Next Issue the other versions! Still, it’s easily one of the best episodes Click/tap on an item to jump to that article. from the first series, if not THE best, and it’s importance in Click/tap the red square at the end of each article to return here. guiding the style of the show cannot be understated. And that’s simple enough that Lister can understand it. “So what is it?” “Thankski Verski Influenced by friends and professionals Muchski Budski!” within the Transformers fandom, I’ve opted to take a leaf out of their book and try and Many thanks to Jordan Hall and James Telfor for create a Red Dwarf fanzine in the vein of providing thier own photographs, memories and other a partwork - where each issue will take a information about the studio filming of Future Echoes deep in-depth dive into a specific episode for this issue. -

Orientation Acquisitions: Heterosexual, Homosexual, Smoking, Disordered Eating, Etc.)

Choosing An Orientation? -- Entrenched Learnings (Vol. 2) (Orientation Acquisitions: Heterosexual, Homosexual, Smoking, Disordered Eating, Etc.) L.L. Morton, PhD Professor Emeritus University of Windsor Faculty of Education 401 Sunset Avenue Windsor, Ontario N9B 3P4 [email protected] DRAFT August 2013 iteration © Dr. L. L. Morton Running Head: A Smoking Analogy Informs Psychological Orientations A Smoking Analogy Informs Psychological Orientations-- 2 Preface ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 16 Chapter 1: Thinking ..................................................................................................................... 29 Analogical Thinking ................................................................................................................ 29 Multiple-Constraints Theory ............................................................................................ 29 Structure-Mapping Theory ............................................................................................... 30 Analogical Thinking In Rational Contexts .............................................................................. 33 Development—A -

WO 2010/123791 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 28 October 2010 (28.10.2010) WO 2010/123791 Al (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agent: LETT, Renne, M.; E. I .du Pont de Nemours and C07D 417/14 (2006.01) AOlN 43/80 (2006.01) Company, Legal Patent Records Center, 4417 Lancaster Pike, Wilmington, Delaware 19805 (US). (21) International Application Number: PCT/US20 10/03 1546 (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, (22) Date: International Filing AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, 19 April 2010 (19.04.2010) CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (25) Filing Language: English DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (26) Publication Language: English KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (30) Priority Data: ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, 61/171,573 22 April 2009 (22.04.2009) US NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, 61/3 11,5 12 8 March 2010 (08.03.2010) US SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): E. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Unsettling Racial Capitalism

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Unsettling Racial Capitalism: Horror in African American and Native American Fiction A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Colton Scott Saylor Committee in charge: Professor Stephanie Batiste, Chair Professor Felice Blake Professor Candace Waid June 2018 The dissertation of Colton Scott Saylor is approved. ____________________________________________ Candace Waid ____________________________________________ Felice Blake ____________________________________________ Stephanie Batiste, Committee Chair May 2018 Unsettling Racial Capitalism: Horror in African American and Native American Fiction Copyright © 2018 by Colton Scott Saylor iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I now understand the gravity due in thanking those without whom intellectual work would not be possible. “Unsettling Racial Capitalism” exists because of the guidance and support of a group of individuals whom I am lucky enough to call my teachers, colleagues, friends, and family. First, to my dissertation committee, Drs. Stephanie Batiste, Felice Blake, and Candace Waid: your collective brilliance and compassion is what gave this project shape. You are all the standard by which I measure myself as a teacher and scholar. Dr. Batiste, I will forever be in debt for your diligence in ensuring that this dissertation reflected my own passions; Dr. Blake, your generosity as a mentor and your own commitment to action beyond the classroom have led me to the most impactful experiences of my career, and for that you have all my gratitude; and Dr. Waid, it is no hyperbole to state that this dissertation would not be without the power and genius that defines your scholarship and your teaching. I will always remember the lessons you have imparted about what it means to advocate for your students and what it takes to reckon with the weight of history.