Book A5 W 21/09/2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HPSC0011 STS Perspectives on Big Problems Course Syllabus

HPSC0011 STS Perspectives on Big Problems Course Syllabus 2020-21 session | STS Staff, course coordinator Dr Cristiano Turbil | [email protected] Course Information This module introduces students to the uses of STS in solving big problems in the contemporary world. Each year staff from across the spectrum of STS disciplines – History, Philosophy, Sociology and Politics of Science – will come together to teach students how different perspectives can shed light on issues ranging from climate change to nuclear war, private healthcare to plastic pollution. Students have the opportunity to develop research and writing skills, and assessment will consist of a formative and a final essay. Students also keep a research notebook across the course of the module This year’s topic is Artificial Intelligence. Basic course information Moodle Web https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=7420 site: Assessment: Formative assessment and essay Timetable: See online timetable Prerequisites: None Required texts: Readings listed below Course tutor(s): STS Staff, course coordinator Dr Cristiano Turbil Contact: [email protected] | Web: https://moodle.ucl.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=7420 Office location: Online for TERM 1 Schedule UCL Date Topic Activity Wk 1 & 2 20 7 Oct Introduction and discussion of AI See Moodle for details as ‘Big Problem’ (Turbil) 3 21 14 Oct Mindful Hands (Werret) See Moodle for details 4 21 14 Oct Engineering Difference: the Birth See Moodle for details of A.I. and the Abolition Lie (Bulstrode) 5 22 21 Oct Measuring ‘Intelligence’ (Cain & See Moodle for details Turbil) 6 22 21 Oct Artificial consciousness and the See Moodle for details ‘race for supremacy’ in Erewhon’s ‘The Book of the Machines’ (1872) (Cain & Turbil) 7 & 8 23 28 Oct History of machine intelligence in See Moodle for details the twentieth century. -

The BG News October 28, 2004

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-28-2004 The BG News October 28, 2004 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 28, 2004" (2004). BG News (Student Newspaper). 7344. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/7344 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. j^k M V Bowling Green State University THURSDAY October 28, 2004 Country looking forward ^^ 1 111 1 PM SHOWERS toIB MAC tourney; PAGE 9 KII I -i-WHN1 A \ \ \< ) HIGH63 LOW48 www.bgnews.com —U VJ ■■" VOLUME 99 ISSUE 56 Political artwork stolen from FAC Six student posters said she feels discouraged and BUSH KERRY fears that the artwork theft were taken last week may hinder students' chances from Fine Arts Center. TWO FLAVORS OF COLA of entering the contest. "It was disrespectful and a violation of their first amend- By lanell Kingsborough SENIOR REPORTER ment rights," Rusnak said. She feels that taking the If il was any other year, the artwork from the display artwork of students in the was one way of silencing the Intermediate Digital Imaging students' voices. course might have lasted longer "Whether people agreed on the wall than one or two with the student's messages days- BOIH BAO (OR vou or not, that did not give Ehem Six posters disappeared last Graphic Created the right to take matters into week from the Fine Arts Center. -

Driving in Wa • a Guide to Rest Areas

DRIVING IN WA • A GUIDE TO REST AREAS Driving in Western Australia A guide to safe stopping places DRIVING IN WA • A GUIDE TO REST AREAS Contents Acknowledgement of Country 1 Securing your load 12 About Us 2 Give Animals a Brake 13 Travelling with pets? 13 Travel Map 2 Driving on remote and unsealed roads 14 Roadside Stopping Places 2 Unsealed Roads 14 Parking bays and rest areas 3 Litter 15 Sharing rest areas 4 Blackwater disposal 5 Useful contacts 16 Changing Places 5 Our Regions 17 Planning a Road Trip? 6 Perth Metropolitan Area 18 Basic road rules 6 Kimberley 20 Multi-lingual Signs 6 Safe overtaking 6 Pilbara 22 Oversize and Overmass Vehicles 7 Mid-West Gascoyne 24 Cyclones, fires and floods - know your risk 8 Wheatbelt 26 Fatigue 10 Goldfields Esperance 28 Manage Fatigue 10 Acknowledgement of Country The Government of Western Australia Rest Areas, Roadhouses and South West 30 Driver Reviver 11 acknowledges the traditional custodians throughout Western Australia Great Southern 32 What to do if you breakdown 11 and their continuing connection to the land, waters and community. Route Maps 34 Towing and securing your load 12 We pay our respects to all members of the Aboriginal communities and Planning to tow a caravan, camper trailer their cultures; and to Elders both past and present. or similar? 12 Disclaimer: The maps contained within this booklet provide approximate times and distances for journeys however, their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Main Roads reserves the right to update this information at any time without notice. To the extent permitted by law, Main Roads, its employees, agents and contributors are not liable to any person or entity for any loss or damage arising from the use of this information, or in connection with, the accuracy, reliability, currency or completeness of this material. -

Bushfire Brigade Annual General Meeting

BUSHFIRE BRIGADE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING AGENDA FOR THE SHIRE OF MINGENEW BUSHFIRE BRIGADES’ ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING TO BE HELD AT THE SHIRE CHAMBERS ON 25 MARCH 2019 COMMENCING AT 6PM. 1.0 DECLARATION OF OPENING 2.0 RECORD OF ATTENDANCE / APOLOGIES ATTENDEES To be confirmed APOLOGIES Vicki Booth – A/Area Officer – Fire Services Midwest (DFES) 3.0 CONFIRMATION OF PREVIOUS MEETING MINUTES 3.1 BUSHFIRE BRIGADES’ MEETING HELD 02 OCTOBER 2018 BRIGADES’ DECISION – ITEM 3.1 Moved: Seconded: That the minutes of the Bushfire Brigades’ Annual General Meeting of the Shire of Mingenew held 02 October 2018 be confirmed as a true and accurate record of proceedings. VOTING DETAILS: 4.0 OFFICERS REPORTS 4.1 Chief Bush Fire Control Officer Report- Murray Thomas • Overview of the 2018/19 Fire Season • Gazetted change in Shires Restricted Burning Times- now changed from the 17th September to the 1st October. All other timeframes remain the same (Prohibited- 1 Nov- 31 Jan, Restricted 1 October-15 March, open season 16 March- 30 September). This means that the CBFCO can now shorten or lengthen that new restricted date by 14 days depending on seasonal conditions (so restricted timeframe can potentially be pushed out to 17 September-31 October or shortened to 14 October-31 October). 4.2 Captains Reports- All Captains to remark on level of training of its volunteers and any identified gaps or training requirements. MINGENEW BUSHFIRE ADVISORY COMMITTEE MEETING AGENDA – 26 September 2017 4.2.1 Yandanooka 4.2.2 Lockier 4.2.3 Guranu 4.2.4 Mingenew North 4.2.5 Mingenew Town 4.3 Shire CEO Report • 2017/18 Operating Grant has been fully expended and acquitted. -

Surgery at Sea: an Analysis of Shipboard Medical Practitioners and Their Instrumentation

Surgery at Sea: An Analysis of Shipboard Medical Practitioners and Their Instrumentation By Robin P. Croskery Howard April, 2016 Director of Thesis: Dr. Lynn Harris Major Department: Maritime Studies, History Abstract: Shipboard life has long been of interest to maritime history and archaeology researchers. Historical research into maritime medical practices, however, rarely uses archaeological data to support its claims. The primary objective of this thesis is to incorporate data sets from the medical assemblages of two shipwreck sites and one museum along with historical data into a comparative analysis. Using the methods of material culture theory and pattern recognition, this thesis will explore changes in western maritime medical practices as compared to land-based practices over time. Surgery at Sea: An Analysis of Shipboard Medical Practitioners and Their Instrumentation FIGURE I. Cautery of a wound or ulcer. (Gersdorff 1517.) A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History Program in Maritime Studies East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Maritime Studies By Robin P. Croskery Howard 2016 © Copyright 2016 Robin P. Croskery Howard Surgery at Sea: An Analysis of Shipboard Medical Practitioners and Their Instrumentation Approved by: COMMITTEE CHAIR ___________________________________ Lynn Harris (Ph.D.) COMMITTEE MEMBER ____________________________________ Angela Thompson (Ph.D.) COMMITTEE MEMBER ____________________________________ Jason Raupp (Ph.D.) COMMITTEE MEMBER ____________________________________ Linda Carnes-McNaughton (Ph.D.) DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CHAIR ____________________________________ Christopher Oakley (Ph.D.) GRADUATE SCHOOL DEAN ____________________________________ Paul J. Gemperline (Ph.D.) Special Thanks I would like to thank my husband, Bernard, and my family for their love, support, and patience during this process. -

Ministerial Decisions at at 12 October 2018

MINISTERIAL DECISIONS AS AT OCTOBER 2020 Recently received Awaiting decision pursuant to section 45(7) of Pending submission to Pending decision by Ministerial decision the Environmental Protection Act 1986 Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Minister for Aboriginal Affairs APPLICANT / MINISTERIAL LAND PURPOSE LANDOWNER DECISION September 2020 Lot 140 on DP 39512, CT 2227/905, 140 South Western Highway, Land Act No. 11238201, Lot 141 on DP 39512, CT 2227/906, 141 South Western Highway, Land Act No. 11238202, 202 Vittoria Road, Land Act No. 11891696, Glen Iris. Pending Intersection Vittoria Road Lot 201 on DP 57769, CT 2686/979, 201 submission to Main Roads South Western Highway South Western Highway, Land Act No. Minister for Western Australia upgrade and Bridge 0430 11733330, Lot 202 on DP 56668, CT Aboriginal Affairs replacement, Picton. 2754/978, Picton. Road Reserve, Land Act No.s 1575861, 11397280, 11397277, 1347375, and 1292274. Unallocated Crown Land, South Western Highway, Land Act No.s 11580413, 1319074 and 1292275, Picton. Pending Fortifying Mining Pty Ltd – Tenements M25/369, P25/2618, submission to Fortify Mining Pty Majestic North Project. To P25/2619, P25/2620, and P25/2621, Minister for Ltd undertake exploration and Goldfields. Aboriginal Affairs resource delineation drilling Reserve 34565, Lot 11835 on Plan Pending 240379, CT 3141/191, Coode Street, Landscape enhancement submission to City of South South Perth, Land Act No. 1081341 and and river restoration. To Minister for Perth Reserve 48325, Lot 301 on Plan 47451, construct the Waterbird Aboriginal Affairs CT 3151/548, 171 Riverside Drive, Land Refuge Act No. 11714773, Perth Pending Able Planning and Lot 501 on Plan 23800, CT 2219/673, submission to Lot 501 Yalyalup Urban Project 113 Vasse Highway, Yalyalup, Land Act Minister for Subdivision. -

Gateways and Shipping During the Early Modern Times - the Gothenburg Example 1720-1804

Gateways and shipping during the early modern times - The Gothenburg example 1720-1804 Authors: Dr. Per Hallén, Dr. Lili-Annè Aldman & Dr. Magnus Andersson At: Dept of Economic History, School of Business, Economics and Law University of Gothenburg Box 720 SE 405 30 Gothenburg Paper for the Ninth European Social Science History Conference (ESSHC): session: Commodity Chains in the First Period of Globalization in Glasgow 11– 14 April, 2012. [Please do not quote without the author’s permission.] 1 Table of contents: ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Background ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Institutional factors .............................................................................................................................. 6 Theoretical starting points ................................................................................................................... 8 Method and material ............................................................................................................................ 9 Analysis ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Point frequency ............................................................................................................................. -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

Geology of the Northern Perth Basin, Western Australia

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233726107 Geology of the northern Perth Basin, Western Australia. A field guide Technical Report · June 2005 CITATIONS READS 15 1,069 4 authors: Arthur John Mory David Haig Government of Western Australia University of Western Australia 91 PUBLICATIONS 743 CITATIONS 61 PUBLICATIONS 907 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Stephen Mcloughlin Roger M. Hocking Swedish Museum of Natural History Geological Survey of Western Australia 143 PUBLICATIONS 3,298 CITATIONS 54 PUBLICATIONS 375 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Lower Permian bryozoans of Western Australia View project Late Palaeozoic palynology of Dronning Maud Land, Antarctica View project All content following this page was uploaded by Stephen Mcloughlin on 05 May 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. Department of Industry and Resources RECORD GEOLOGY OF THE NORTHERN PERTH 2005/9 BASIN, WESTERN AUSTRALIA — A FIELD GUIDE by A. J. Mory, D. W. Haig, S. McLoughlin, and R. M. Hocking Geological Survey of Western Australia GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Record 2005/9 GEOLOGY OF THE NORTHERN PERTH BASIN, WESTERN AUSTRALIA — A FIELD GUIDE by A. J. Mory, D. W. Haig1, S. McLoughlin2, and R. M. Hocking 1 School of Earth and Geographical Sciences, The University of Western Australia 2 School of Natural Resource Sciences, Queensland University of Technology Perth 2005 MINISTER FOR STATE DEVELOPMENT Hon. -

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia By: D.A. Cumming, D. Garratt, M. McCarthy, A. WoICe With <.:unlribuliuns from Albany Seniur High Schoul. M. Anderson. R. Howard. C.A. Miller and P. Worsley Octobel' 1995 @WAUUSEUM Report: Department of Matitime Archaeology, Westem Australian Maritime Museum. No, 98. Cover pholograph: A view of Halllelin Bay in iL~ heyday as a limber porl. (W A Marilime Museum) This study is dedicated to the memory of Denis Arthur Cuml11ing 1923-1995 This project was funded under the National Estate Program, a Commonwealth-financed grants scheme administered by the Australian HeriL:'lge Commission (Federal Government) and the Heritage Council of Western Australia. (State Govenlluent). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Heritage Council of Western Australia Mr lan Baxter (Director) Mr Geny MacGill Ms Jenni Williams Ms Sharon McKerrow Dr Lenore Layman The Institution of Engineers, Australia Mr Max Anderson Mr Richard Hartley Mr Bmce James Mr Tony Moulds Mrs Dorothy Austen-Smith The State Archive of Westem Australia Mr David Whitford The Esperance Bay HistOIical Society Mrs Olive Tamlin Mr Merv Andre Mr Peter Anderson of Esperance Mr Peter Hudson of Esperance The Augusta HistOIical Society Mr Steve Mm'shall of Augusta The Busselton HistOlical Societv Mrs Elizabeth Nelson Mr Alfred Reynolds of Dunsborough Mr Philip Overton of Busselton Mr Rupert Genitsen The Bunbury Timber Jetty Preservation Society inc. Mrs B. Manea The Bunbury HistOlical Society The Rockingham Historical Society The Geraldton Historical Society Mrs J Trautman Mrs D Benzie Mrs Glenis Thomas Mr Peter W orsley of Gerald ton The Onslow Goods Shed Museum Mr lan Blair Mr Les Butcher Ms Gaye Nay ton The Roebourne Historical Society. -

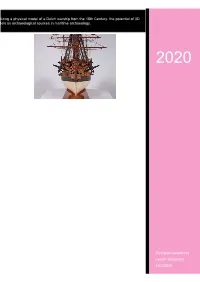

Digitizing a Physical Model of a Dutch Warship from the 18Th Century: the Potential of 3D Models As Archaeological Sources in Maritime Archaeology

Digitizing a physical model of a Dutch warship from the 18th Century: the potential of 3D models as archaeological sources in maritime archaeology. 2020 Georgios Karadimos Leiden University 10/2/2020 Front page figure: the bow of the physical model (figure by author). 1 Digitizing a Physical model of a Dutch warship from the 18th Century: the potential of 3D models as archaeological sources in maritime ar- chaeology. Georgios Karadimos -s1945211 Msc Thesis - 4ARX-0910ARCH. Dr. Lambers. Digital Archaeology Msc. University of Leiden, Faculty of Archaeology. Leiden 10/02/2020-Final version. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS. Acknowledgments ............................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 6 1.1) OVERVIEW .............................................................................................. 6 1.2) MOTIVATIONS FOR THE PROJECT. ...................................................... 7 1.3) AIMS AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS. ..................................................... 9 1.4) THESIS OVERVIEW .............................................................................. 11 1.5) RESEARCH METHOD ........................................................................... 12 CHAPTER 2: THE PHYSICAL SHIP MODEL IN THE DUTCH MARITIME HISTORICAL CONTEXT. .............................................................................. 15 2.1) THE DUTCH NAVY BETWEEN 1720-1750 ........................................... -

Map Matters, the Newsletter of the News Australia on the Map Division of the Australasian Hydrographic Society

www.australiaonthemap.org.au I s s u e Map 1 Matters Issue 7 August 2009 Inside this issue Welcome to the 'Winter' edition of Map Matters, the newsletter of the News Australia on the Map Division of the Australasian Hydrographic Society. World Hydrography Day 2009 If you have any contributions or suggestions for National Library Map Matters, you can email them to me at: stoked at acquiring [email protected], or post them to me at: rare charts GPO Box 1781, Canberra, 2601 Sticky Charts Education award Frank Geurts 2009 Editor Projects update Members welcome Contacts How to contact the AOTM Division News World Hydrography Day 2009 Since the United Nations officially recognised 21 June as World Hydrography Day in 2005 it has been marked around the world each year by the international hydrographic community. And this year was no exception. Different divisions of the Australasian Hydrographic Society organised events as befitted the occasion. In Perth the WA Region had a guided tour of the Journeys of Enlightenment exhibition at the Maritime Museum, followed by a lecture on the “Mapping the Coast” database. In New Zealand a seminar and dinner were held. Similarly, the Eastern Australian Region conducted a seminar at the Royal Automobile Club in Sydney, which was followed by a dinner. Rupert Gerritsen accepts the Literary Achievement Award on behalf of Associate Professor Bill Richardson. I, as Chair of the Australia on the Map Division, attended the Sydney event. The Royal Automobile Club is a grand old building, well suited to the occasion. The theme of the day-long seminar was “Taking Stock of the Industry”.