BLOCK 4 CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS Cultural Developments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – History Notes

Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – History Notes Posted On April 28, 2020 By Cgpsc.Info Home » CGPSC Notes » History Notes » Gupta Empire and Their Rulers Gupta Empire and Their Rulers – The Gupta period marks the important phase in the history of ancient India. The long and e¸cient rule of the Guptas made a huge impact on the political, social and cultural sphere. Though the Gupta dynasty was not widespread as the Maurya Empire, but it was successful in creating an empire that is signiÛcant in the history of India. The Gupta period is also known as the “classical age” or “golden age” because of progress in literature and culture. After the downfall of Kushans, Guptas emerged and kept North India politically united for more than a century. Early Rulers of Gupta dynasty (Gupta Empire) :- Srigupta – I (270 – 300 C.E.): He was the Ûrst ruler of Magadha (modern Bihar) who established Gupta dynasty (Gupta Empire) with Pataliputra as its capital. Ghatotkacha Gupta (300 – 319 C.E): Both were not sovereign, they were subordinates of Kushana Rulers Chandragupta I (319 C.E. to 335 C.E.): Laid the foundation of Gupta rule in India. He assumed the title “Maharajadhiraja”. He issued gold coins for the Ûrst time. One of the important events in his period was his marriage with a Lichchavi (Kshatriyas) Princess. The marriage alliance with Kshatriyas gave social prestige to the Guptas who were Vaishyas. He started the Gupta Era in 319-320C.E. Chandragupta I was able to establish his authority over Magadha, Prayaga,and Saketa. Calendars in India 58 B.C. -

Traditional Knowledge Systems and the Conservation and Management of Asia’S Heritage Rice Field in Bali, Indonesia by Monicavolpin (CC0)/Pixabay

ICCROM-CHA 3 Conservation Forum Series conservation and management of Asia’s heritage conservation and management of Asia’s Traditional Knowledge Systems and the Systems Knowledge Traditional ICCROM-CHA Conservation Forum Series Forum Conservation ICCROM-CHA Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Rice field in Bali, Indonesia by MonicaVolpin (CC0)/Pixabay. Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Edited by Gamini Wijesuriya and Sarah Court Forum on the applicability and adaptability of Traditional Knowledge Systems in the conservation and management of heritage in Asia 14–16 December 2015, Thailand Forum managers Dr Gamini Wijesuriya, Sites Unit, ICCROM Dr Sujeong Lee, Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), Republic of Korea Forum advisors Dr Stefano De Caro, Former Director-General, ICCROM Prof Rha Sun-hwa, Administrator, Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), Republic of Korea Mr M.R. Rujaya Abhakorn, Centre Director, SEAMEO SPAFA Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts Mr Joseph King, Unit Director, Sites Unit, ICCROM Kim Yeon Soo, Director International Cooperation Division, Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), Republic of Korea Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Edited by Gamini Wijesuriya and Sarah Court ISBN 978-92-9077-286-6 © 2020 ICCROM International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property Via di San Michele, 13 00153 Rome, Italy www.iccrom.org This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution Share Alike 3.0 IGO (CCBY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo). -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati . & Dr. K. Muniratnam Director i/c, Epigraphy, ASI, Mysore. Dr. V. Selvakumar Tamil University, Thanjavoor. Prof. P. Bhaskar Reddy Sri Venkateswara University, Tirupati. 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Indian Epigraphy Epigraphy as a Source for the Social, Economic and Module Name/Title Cultural History of India Module Id IC / IEP / 04 Knowledge of English Pre requisites Basic knowledge on of Indian history Understanding Social, economic and Cultural History Objectives Finding out how epigraphy is useful for reconstructing Social, economic and cultural history Keywords Cultural History, Epigraphy, Inscriptions E-text (Quadrant-I) : 1. Introduction Epigraphical documents (i.e. inscriptions found on stones and copper plates) are the most important source for the historical period. However, the data from the inscriptions cannot be used in isolation or in a selective manner and the dataset needs to be analysed collectively and correlated with literature, archaeology, art historical vestiges, languages and oral traditions, for a better understanding of history. In the earlier module, we exclusively focused on how epigraphy is useful for the reconstruction of the political history. In this module, let’s look into how epigraphy is useful for understanding the social, economic and cultural history of India. As students of history, you need to look at the inscriptions and the dataset that they offer, very critically. By carefully reading the inscriptions and understanding the meanings of the words, the multiple dimensions of history can be brought to light. -

Namdev Life and Philosophy Namdev Life and Philosophy

NAMDEV LIFE AND PHILOSOPHY NAMDEV LIFE AND PHILOSOPHY PRABHAKAR MACHWE PUBLICATION BUREAU PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala 1990 Second Edition : 1100 Price : 45/- Published by sardar Tirath Singh, LL.M., Registrar Punjabi University, Patiala and printed at the Secular Printers, Namdar Khan Road, Patiala ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the Punjabi University, Patiala which prompted me to summarize in tbis monograpb my readings of Namdev'\i works in original Marathi and books about him in Marathi. Hindi, Panjabi, Gujarati and English. I am also grateful to Sri Y. M. Muley, Director of the National Library, Calcutta who permitted me to use many rare books and editions of Namdev's works. I bave also used the unpubIi~bed thesis in Marathi on Namdev by Dr B. M. Mundi. I bave relied for my 0pIDlOns on the writings of great thinkers and historians of literature like tbe late Dr R. D. Ranade, Bhave, Ajgaonkar and the first biographer of Namdev, Muley. Books in Hindi by Rabul Sankritya)'an, Dr Barathwal, Dr Hazariprasad Dwivedi, Dr Rangeya Ragbav and Dr Rajnarain Maurya have been my guides in matters of Nath Panth and the language of the poets of this age. I have attempted literal translations of more than seventy padas of Namdev. A detailed bibliography is also given at the end. I am very much ol::lig(d to Sri l'and Kumar Shukla wbo typed tbe manuscript. Let me add at the end tbat my family-god is Vitthal of Pandbarpur, and wbat I learnt most about His worship was from my mother, who left me fifteen years ago. -

HT-101 History.Pdf

Directorate of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF JAMMU JAMMU SELF LEARNING MATERIAL B. A. SEMESTER - I SUBJECT : HISTORY Units I-IV COURSE No. : HT-101 Lesson No. 1-19 Stazin Shakya Course Co-ordinator http:/www.distanceeducation.in Printed and published on behalf of the Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, Jammu by the Director, DDE, University of Jammu, Jammu ANCIENT INDIA COURSE No. : HT - 101 Course Contributors : Content Editing and Proof Reading : Dr. Hina S. Abrol Dr. Hina S. Abrol Prof. Neelu Gupta Mr. Kamal Kishore Ms. Jagmeet Kour c Directorate of Distance Education, University of Jammu, Jammu, 2019 • All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission in writing from the DDE, University of Jammu. • The script writer shall be responsible for the lesson/script submitted to the DDE and any plagiarism shall be his/her entire responsibility. Printed at :- Pathania Printers /19/ SYLLABUS B.A. Semester - I Course No. : HT - 101 TITLE : ANCIENT INDIA Unit-I i. Survey of literature - Vedas to Upanishads. ii. Social Life in Early & Later Vedic Age. iii. Economic Life in Early & Later Vedic Age. iv. Religious Life in Early & Later Vedic Age. Unii-II i. Life and Teachings of Mahavira. ii. Development of Jainism after Mahavira. iii. Life and Teachings of Buddha. iv. Development of Buddhism : Four Buddhist Councils and Mahayana Sect. Unit-III i. Origin and Sources of Mauryas. ii. Administration of Mauryas. iii. Kalinga War and Policy of Dhamma Vijaya of Ashoka. iv. Causes of Downfall of the Mauryas. -

Comprehensive-Test-1-Explanations

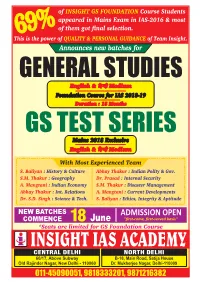

GENERAL STUDIES MAINS SPECIAL BATCH - 2018 Important Traditional & Current Issues World History, Geography, Environment & Ecology, Polity & Governance Internal Security, Disaster Management, International Relations Economic Development, Social Justice, Science & Technology Ethics, Int. & Aptitude with more than 100 Case Studies Covering More than 800 Marks WITH BEST EVER TEAM S. BALIYAN , ABHAY THAKUR, DR. VIVEK, A. MANGTANI, A.N. REDDY, A.S. SHEKAR, & S.M. THAKUR NEW BATCHES Course Duration COMMENCE 18 June 12 Weeks INSIGHT IAS ACADEMY India's Best Institute for Civil Services Prep. CENTRAL DELHI NORTH DELHI 011-45090051 60/17, Above Subway B-18, Main Road, Satija House, 09818333201 Old Rajinder Nagar, New Delhi - 110060 Dr. Mukherjee Nagar, Delhi - 110009 09871216382 E-MAIL : [email protected] • WEBSITE : www.insightiasacademy.com INSIGHT GEN.STUDIES & CSAT COMPREHENSIVE TEST – 1 (FULL MOCK TEST) 1. B Recapitalisation bonds are dedicated bonds to be issued at the behest of the government for recapitalizing the trouble hit Public Sector Banks (PSBs). Bonds worth of Rs 1.35 trillion is to be issued to inject capital into PSBs who are affected by the high level of NPAs. Recapitalization bonds are proposed as a part of the Rs 2.11 trillion capital infusion package declared by the government. The money obtained from the sale of bonds will be injected into the PSBs as government equity funding. The bond will be subscribed by the public sector banks themselves. Fund from the issue of bonds will be used to subscribe shares of PSBs and will be treated as additional government equity or capital. The government has recently fixed the coupon rate - up to 7.68% - for the Rs 80, 000 crore recapitalisation bonds to be given to 20 public sector banks during the current fiscal for meeting the regulatory capital requirement and growth needs. -

Indian History

INDIAN HISTORY PRE-HISTORIC as a part of a larger area called Pleistocene to the end of the PERIOD Jambu-dvipa (The continent of third Riss, glaciation. Jambu tree) The Palaeolithic culture had a The pre-historic period in the The stages in mans progress from duration of about 3,00,000 yrs. history of mankind can roughly Nomadic to settled life are The art of hunting and stalking be dated from 2,00,000 BC to 1. Primitive Food collecting wild animals individually and about 3500 – 2500 BC, when the stage or early and middle stone later in groups led to these first civilization began to take ages or Palaeolithic people making stone weapons shape. 2 . Advanced Food collecting and tools. The first modern human beings stage or late stone age or The principal tools are hand or Homo Sapiens set foot on the Mesolithic axes, cleavers and chopping Indian Subcontinent some- tools. The majority of tools where between 2,00,000 BC and 3. Transition to incipient food- found were made of quartzite. 40,000 BC and they soon spread production or early Neolithic They are found in all parts of through a large part of the sub- 4. settled village communities or India except the Central and continent including peninsular advanced neolithic/Chalco eastern mountain and the allu- India. lithic and vial plain of the ganges. They continuously flooded the 5. Urbanisation or Bronze age. People began to make ‘special- Indian subcontinent in waves of Paleolithic Age ized tools’ by flaking stones, migration from what is present which were pointed on one end. -

History – MAURYAN & GUPTA DYNASTY

Y215 TODAY TOPIC History – MAURYAN & GUPTA DYNASTY History – MAURYAN & GUPTA DYNASTY THE MAURYAN DYNASTY Chandragupta Maurya (322 BC – 297 BC ) : With the help of Chanakya, known as Kautilya or Vishnugupta, he overthrew the Nandas & established the rule of the Maurya dynasty. Built a vast empire, which included not only good portions of Bihar & Bengal, but also western & north western India & the Deccan. This account is given by Megasthenes (A Greek ambassador sent by Seleucus to the court of Chandragupta Maurya in his book Indica. We also get the details from the Arthashastra of Kautilya. Chandragupta adopted Jainism & went to Sravanabelagola (near Mysore) with Bhadrabahu, where he died by slow starvation. History – MAURYAN & GUPTA DYNASTY Bindusara (297 BC – 273 BC ) : Chandragupta Maurya was succeeded by his son Bindusara in 297 BC. He is said to have conquered ‘the land between the 2 seas’, i.e., the Arabian Sea & Bay of Bengal. History – MAURYAN & GUPTA DYNASTY Ashoka (269 – 232 B(C): Ashoka was the most famous Mauryan king and one of the greatest rulers. Ashoka assumed the title of Priyadarshi (pleasing to look at) and Devanampriya (beloved of Gods). In the Sarnath inscription, he adopted the third title, i.e. Dharmshoka. History – MAURYAN & GUPTA DYNASTY Ashoka’s Rock Edicts - Major rock edicts (a set of 14 inscription) found at following 8 places: Dhauli, Girnar, Jaduguda, Kalsi, Mansehra, Shahbazgarhi, Sopara and Yenagardi. Minor rock edicts found at 13 places: Bairat, Brahmagiri, Gavimath Gajarra, Jatinga-Rameshwar, Maski, Palkigunda, Meadagiri, Rupanath, Sasaram, Siddhapur, Suvarnagiri and Verragudi. History – MAURYAN & GUPTA DYNASTY Major rock edicts- 1st Major Rock Edict- Prohibition of animal sacrifice. -

Indian HISTORY

Indian HISTORY AncientIndia PRE-HISTORICPERIOD G The Mesolithic people lived on hunting, fishing and food-gathering. At a later G The recent reported artefacts from stage, they also domesticated animals. Bori in Maharashtra suggest the appearance of human beings in India G The people of the Palaeolithic and around 1.4 million years ago. The early Mesolithic ages practised painting. man in India used tools of stone, G Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh, is a roughly dressed by crude clipping. striking site of pre-historic painting. G This period is therefore, known as the Stone Age, which has been divided into The Neolithic Age The Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age (4000-1000 BC) The Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age G The people of this age used tools and The Neolithic or New Stone Age implements of polished stone. They particularly used stone axes. The Palaeolithic Age G It is interesting that in Burzahom, (500000-9000 BC) domestic dogs were buried with their masters in their graves. G Palaeolithic men were hunters and food G First use of hand made pottery and gatherers. potter wheel appears during the G They had no knowledge of agriculture, Neolithic age. Neolithic men lived in fire or pottery; they used tools of caves and decorated their walls with unpolished, rough stones and lived in hunting and dancing scenes. cave rock shelters. G They are also called Quartzite men. The Chalcolithic Age G Homo Sapiens first appeared in the (4500-3500 BC) last phase of this period. The metal implements made by them G This age is divided into three phases were mostly the imitations of the stone according to the nature of the stone forms. -

Copyright by Matthew David Milligan 2010

Copyright by Matthew David Milligan 2010 The Thesis Committee for Matthew David Milligan Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: A Study of Inscribed Reliefs within the Context of Donative Inscriptions at Sanchi APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Oliver Freiberger Janice Leoshko A Study of Inscribed Reliefs within the Context of Donative Inscriptions at Sanchi by Matthew David Milligan, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin August 2010 Dedication In memory of Dr. Selva J. Raj, and for all of my teachers, past, present, and future. Acknowledgements I’d like to begin by thanking my two co-supervisors, Dr. Oliver Freiberger and Dr. Janice Leoshko. Their comments, insights, and--most of all, patience--have given me the opportunity to learn much during this process. I am grateful to other professors at the University of Texas at Austin who have taught me much these past few years, including the arduous task of teaching me Sanskrit. For this, I am indebted to Dr. Edeltraud Harzer, Dr. Patrick Olivelle, and Dr. Joel Brereton. I extend much appreciation to those in India who have helped me research, travel, and learn Prakrit. First, I thank Dr. Narayan Vyas (Retd. Superintending Archaeologist, ASI Bhopal), for helping to arrange my research opportunity at Sanchi in 2009. Also at Sanchi, S.K. Varma--who may yet prove to be the incarnation of Emperor Aśoka-- assisted a great deal, as well as P.L. -

The Locational Geography of Ashokan Inscriptions in the Indian Subcontinent

Antiquity http://journals.cambridge.org/AQY Additional services for Antiquity: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Finding history: the locational geography of Ashokan inscriptions in the Indian subcontinent Monica L. Smith, Thomas W. Gillespie, Scott Barron and Kanika Kalra Antiquity / Volume 90 / Issue 350 / April 2016, pp 376 - 392 DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2016.6, Published online: 06 April 2016 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0003598X16000065 How to cite this article: Monica L. Smith, Thomas W. Gillespie, Scott Barron and Kanika Kalra (2016). Finding history: the locational geography of Ashokan inscriptions in the Indian subcontinent. Antiquity, 90, pp 376-392 doi:10.15184/aqy.2016.6 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/AQY, IP address: 128.97.195.154 on 07 Apr 2016 Finding history: the locational geography of Ashokan inscriptions in the Indian subcontinent Monica L. Smith1, Thomas W. Gillespie2, Scott Barron2 & Kanika Kalra3 The Mauryan dynasty of the third century BC was the first to unite the greater part of the Indian subcontinent under a single ruler, yet its demographic geography remains largely uncertain. Here, the HYDE 3.1 database of past population and land-use is used to offer insights into key aspects of Mauryan political geography through the locational analysis of the Ashokan edicts, which are the first stone inscriptions known from the subcontinent and which constitute the first durable statement of Buddhist-inspired beliefs. The known distribution of rock and pillar edicts across the subcontinent can be combined with HYDE 3.1 to generate predictive models for the location of undiscovered examples and to investigate the relationship between political economy and religious activities in an early state. -

To Download a Free Pdf of the Bhagavad Gita By

Krishna’s Bhagavad Gita Translated by Dayananda Dayananda Media By Dayananda Books Modern Culture – A Dangerous Experiment Bhagavad Gita (translation) Prahlad (a novel) War of the Soul: The Mystical Revolution (Bhagavad-Gita Commentary Volume 1) Booklets Greed, The Gods, and the Environment: Krishna's Solution to Ecological Disaster Sankirtana As It Is All Rights Reserved Copyright © 2018 by Dayananda This book may not be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in whole or in part by any means, including graphic, electronic, or mechanical without the written consent of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. First published in 2018 by Dayananda Media, subsidiary of C&V Media, Gaithersburg, MD Badarayana Vedavyas is the traditional compiler of the Bhagavad Gita, which appears in the great epic, Mahabharata Translations are by Dayananda All the citations made here are searchable on the Internet. Illustrations are in the public domain. Readers are invited to write the author at [email protected]. ISBN-13: 978-0-9978440-3-0 For A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupad Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................... i Acknowledgments ............................................................. iii Preface................................................................................ iv Krishna and Arjuna ............................................................ v Bhagavat Culture .............................................................