Remaking Horror According to the Feminists Or How to Have Your Cake and Eat It, Too

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shooting: Officer Cleared New Light Shed on Motorist’S Possible Take Motive in Pointing Handgun at Police

BASCOM NORRIS COLLISION INJURES ONE Live Oak man Intersection at retires from Bascom Norris and Sisters Welcome top Guard Road was blocked for nearly an hour. post. See Page 3A. See Page 6A. TUESDAY, JULY 1, 2014 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM New laws Shooting: Officer cleared New light shed on motorist’s possible take motive in pointing handgun at police. By MEGAN REEVES March, LCPD said Monday. [email protected] Police also released infor- effect mation that may help explain Lake City Police Officer Mike why the motorist, a registered Lee Barker Lee has been cleared of any sex offender from Tennessee, wrongdoing in the fatal shoot- aimed a handgun at Lee when Jury convened May 20 and filed today FILE ing of an armed felon during he approached his vehicle. Barker’s pickup is pictured (background) a routine DUI checkpoint in The Columbia County Grand E-cigarette ban, SHOOTING continued on 3A following the March 14 shooting. GI Bill among 157 approved. ADVENTURES AT RUM ISLAND Tropical By JIM TURNER The News Service of Florida storm TALLAHASSEE — The state’s record-setting, $77 billion election-year budget may be goes into effect today, along PREVIEW with 157 brewing n Gun-carriers other bills can’t be denied approved Chance of rain insurance. by the n Illegal immi- Legislature in Lake City is grants granted and signed only 50 percent. in-state tuition. n Text messag- by Gov. es added to the Rick Scott. By EMILY STANTON “Do Not Call” The [email protected] program list. -

This Installation Explores the Final Girl Trope. Final Girls Are Used in Horror Movies, Most Commonly Within the Slasher Subgenre

This installation explores the final girl trope. Final girls are used in horror movies, most commonly within the slasher subgenre. The final girl archetype refers to a single surviving female after a murderer kills off the other significant characters. In my research, I focused on the five most iconic final girls, Sally Hardesty from A Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Laurie Strode from Halloween, Ellen Ripley from Alien, Nancy Thompson from A Nightmare on Elm Street and Sidney Prescott from Scream. These characters are the epitome of the archetype and with each girl, the trope evolved further into a multilayered social commentary. While the four girls following Sally added to the power of the trope, the significant majority of subsequent reproductions featured surface level final girls which took value away from the archetype as a whole. As a commentary on this devolution, I altered the plates five times, distorting the image more and more, with the fifth print being almost unrecognizable, in the same way that final girls have become. Chloe S. New Jersey Blood, Tits, and Screams: The Final Girl And Gender In Slasher Films Chloe S. Many critics would credit Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho with creating the genre but the golden age of slasher films did not occur until the 70s and the 80s1. As slasher movies became ubiquitous within teen movie culture, film critics began questioning why audiences, specifically young ones, would seek out the high levels of violence that characterized the genre.2 The taboo nature of violence sparked a powerful debate amongst film critics3, but the most popular, and arguably the most interesting explanation was that slasher movies gave the audience something that no other genre was able to offer: the satisfaction of unconscious psychological forces that we must repress in order to “function ‘properly’ in society”. -

A Cinema of Confrontation

A CINEMA OF CONFRONTATION: USING A MATERIAL-SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR THE HISTORY AND THEORIZATION OF 1970S INDEPENDENT AMERICAN HORROR _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by COURT MONTGOMERY Dr. Nancy West, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2015 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled A CINEMA OF CONFRONTATION: USING A MATERIAL-SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR THE HISTORY AND THEORIZATION OF 1970S INDEPENDENT AMERICAN HORROR presented by Court Montgomery, a candidate for the degree of master of English, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________ Professor Nancy West _________________________________ Professor Joanna Hearne _________________________________ Professor Roger F. Cook ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Dr. Nancy West, for her endless enthusiasm, continued encouragement, and excellent feedback throughout the drafting process and beyond. The final version of this thesis and my defense of it were made possible by Dr. West’s critique. I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Joanna Hearne and Dr. Roger F. Cook, for their insights and thought-provoking questions and comments during my thesis defense. That experience renewed my appreciation for the ongoing conversations between scholars and how such conversations can lead to novel insights and new directions in research. In addition, I would like to thank Victoria Thorp, the Graduate Studies Secretary for the Department of English, for her invaluable assistance with navigating the administrative process of my thesis writing and defense, as well as Dr. -

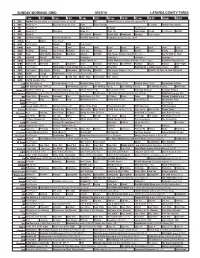

Sunday Morning Grid 12/25/11

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/25/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face/Nation A Gospel Christmas NCAA Show AMA Supercross NFL Holiday Spectacular 4 NBC Holiday Lights Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Wall Street Holiday Lights Extra (N) Å Global Golf Adventure 5 CW Yule Log Seasonal music. (6) (TVG) In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour Disney Parks Christmas Day Parade (N) (TVG) NBA Basketball: Heat at Mavericks 9 KCAL Yule Log Seasonal music. (TVG) Prince Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday Kids News Winning Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program Uptown Girls ›› (2003) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Cuisine Kitchen Kitchen Sweet Life 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Nuestra Navidad República Deportiva en Navidad 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J. Franklin 46 KFTR Paid Tu Estilo Patrulla La Vida An P. -

Fears and the Female Circumstance: Women in 1970S Horror Films Lorian Gish

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 2019 Fears and the Female Circumstance: Women in 1970s Horror Films Lorian Gish Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Fears and the Female Circumstance: Women in 1970s Horror Films Lorian Gish BFA Acting for Film, Television, Voice-over, and Commercials Minor: Classical and Medieval Studies Thesis Advisor: Shaun Seneviratne Film Studies Presentation: May 8th, 2019 Graduation: May 23rd, 2019 Gish 1 Abstract More than ever before, stories commenting on real female fears are invaluable to the natural social progression of film as an art form. The core female-centric themes in prominent 1970s horror films are: coming of age, sexual identity, domesticity, pregnancy, and reproductive rights. This thesis first employs empirical research as groundwork for analysis on specific film works by elaborating on expert opinion of the horror genre as well as its foundational elements. Thus, that analysis of the return of repressed fear(s), audience projection of monster and victim, and male gaze, applies to iconic 1970s horror films such as Carrie (1976), Halloween (1978), and Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Films that capture fear comment on universal themes of female perceptions, through specific visual and textual techniques and practices. Gish 2 Table of Contents Abstract ....................................................................................................................................................... -

1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Brutal Is

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Brutal is an extremely ruthless or cruel. Brutality is the quality of being brutal, cruelty, and savagery. Brutality is one of the factors that are used to increase the terror; the other terror factors are violence, sadism, and graphic blood. Brutality is the part of cruelty. Cruelty is one of the danger signals of personality sickness. A “sick” personality is one in which there is a breakdown in the personality structure which results in poor personal and social adjustment, just as in physical illness, the person does not behave as he normally does (Hurlock, 1979: 389-403). Brutality in A Nightmare on Elm Street Movie is reflected by the main characters, namely Krueger. He kills many teenagers through their dreams, it is called “A Nightmare” and this phenomenon happens on Elm Street. So, it is the reason why this film is entitled “A Nightmare on Elm Street”. A Nightmare on Elm Street is a 2010 American slasher film directed by Samuel Bayer, and written by Wesley Strick and Eric Heisserer, based on a story by Mr. Strick and characters created by Wes Craven; director of photography, Jeff Cutter; edited by Glen Scantlebury; music by Steve Jablonsky; production designer, Patrick Lumb; costumes by Mari-An Ceo; produced by Michael Bay, Andrew Form and Brad Fuller; released by New Line Cinema, Warner Brothers Pictures and Platinum Dunes. Running time: 1 1 2 hour 42 minutes. The film stars Jackie Earle Haley, Kyle Gallner, Rooney Mara, Katie Cassidy, Thomas Dekker and Kellan Lutz. It is a remake of Wes Craven's 1984 film of the same name and the ninth Nightmare film in total, it is designed to reboot the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise. -

Human' Jaspects of Aaonsí F*Oshv ÍK\ Tke Pilrns Ana /Movéis ÍK\ É^ of the 1980S and 1990S

DOCTORAL Sara MarHn .Alegre -Human than "Human' jAspects of AAonsí F*osHv ÍK\ tke Pilrns ana /Movéis ÍK\ é^ of the 1980s and 1990s Dirigida per: Dr. Departement de Pilologia jA^glesa i de oermanisfica/ T-acwIfat de Uetres/ AUTÓNOMA D^ BARCELONA/ Bellaterra, 1990. - Aldiss, Brian. BilBon Year Spree. London: Corgi, 1973. - Aldridge, Alexandra. 77» Scientific World View in Dystopia. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1978 (1984). - Alexander, Garth. "Hollywood Dream Turns to Nightmare for Sony", in 77» Sunday Times, 20 November 1994, section 2 Business: 7. - Amis, Martin. 77» Moronic Inferno (1986). HarmorKlsworth: Penguin, 1987. - Andrews, Nigel. "Nightmares and Nasties" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984:39 - 47. - Ashley, Bob. 77» Study of Popidar Fiction: A Source Book. London: Pinter Publishers, 1989. - Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1992. - Bahar, Saba. "Monstrosity, Historicity and Frankenstein" in 77» European English Messenger, vol. IV, no. 2, Autumn 1995:12 -15. - Baldick, Chris. In Frankenstein's Shadow: Myth, Monstrosity, and Nineteenth-Century Writing. Oxford: Oxford Clarendon Press, 1987. - Baring, Anne and Cashford, Jutes. 77» Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image (1991). Harmondsworth: Penguin - Arkana, 1993. - Barker, Martin. 'Introduction" to Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Media. London and Sydney: Ruto Press, 1984(a): 1-6. "Nasties': Problems of Identification" in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the MecBa. London and Sydney. Ruto Press, 1984(b): 104 - 118. »Nasty Politics or Video Nasties?' in Martin Barker (ed.), 77» Video Nasties: Freedom and Censorship in the Medß. -

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/23/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 Am 7:30 8 Am 8:30 9 Am 9:30 10 Am 10:30 11 Am 11:30 12 Pm 12:30 2 CBS Football New York Giants Vs

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/23/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS Football New York Giants vs. Los Angeles Rams. (6:30) (N) NFL Football Raiders at Jacksonville Jaguars. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Figure Skating F1 Count Formula One Racing 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Regional Coverage. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Rick Steves’ Europe Travel Skills (TVG) Å Age Fix With Dr. Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Tigres República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Home Alone 2: Lost in New York ›› (1992) (PG) Zona NBA Next Day Air › (2009) Donald Faison. -

GODKILLER: Walk Among Us

GODKILLER: Walk Among Us Feature Film Press Kit Contact: Maddy Dawson Halo-8 Entertainment 7336 Santa Monica Blvd #10 LA CA 90046 p. 323-285-5066 f. 323-443-3768 e. [email protected] CAST LANCE HENRIKSEN as Mulciber (Aliens, AVP: Alien Vs Predator) DAVEY HAVOK as Dragos (singer platinum-selling rockers A.F.I.) DANIELLE HARRIS as Halfpipe (Halloween 4, 5; Rob Zombie’s Halloween 1, 2; Hatchet 2) JUSTIN PIERRE as Tommy (singer Warped Tour heroes Motion City Soundtrack) BILL MOSELEY (The Devil’s Rejects, Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, Repo: The Genetic Opera) TIFFANY SHEPIS (The Violent Kind, Nightmare Man) LYDIA LUNCH (underground art icon, star of Richard Kern’s Hardcore Collection) KATIE NISA (Threat) NICKI CLYNE (Battlestar Galactica Syfy TV series) CREW MATT PIZZOLO, writer/director/creator (Threat) ANNA MUCKCRACKER, illustrator BRIAN GIBERSON, producer/animator ALEC EMPIRE, score composer (Atari Teenage Riot) Q&A with Director Matt Pizzolo Q. What is the inspiration behind Godkiller? A. When I was on tour with my first film Threat in Europe, I visited tons of churches and museums and was just really struck by the juxtaposition of pagan art and Christian art… and how much Vatican City resembles Disneyland. It’s as if religions and mythologies and cultures compete for disciples through art… that popular art is a battleground of cultural ideas. So I was inspired to create an ongoing, serialized, pop-art mythology for my people: fuck-ups and weirdos and misfits. Q. Is “illustrated films” just a pretentious way of saying “motion comics?” A. Ha. Yes. Well… No, I don’t think so anyway. -

À La Cinémathèque Française 5 DÉCEMBRE 2012 – 4 MARS 2013 Retrouvez Les Plus Grands fi Lms De L’Histoire Du Cinéma Américain

rétrospective Universal 100 ans - 100 films à La Cinémathèque française 5 DÉCEMBRE 2012 – 4 MARS 2013 Retrouvez les plus grands fi lms de l’histoire du cinéma américain. SAMEDI 8 DÉCEMBRE - 14H30 UNIVERSAL, 100 ANS DE CINÉMA Table ronde animée par Jean-François Rauger, avec Joël Augros et Pierre Berthomieu Précédée de la projection d’Une balle signée X de Jack Arnold. Rétrospective réalisée en partenariat avec HORAIRES + PROGRAMME SUR cinematheque.fr La Cinémathèque française - musée du cinéma è 51, rue de Bercy Paris 12 Crédit : Les Oiseaux d’Alfred Hitchcock (1963) © Universal Studios. DR Grands mécènes de La Cinémathèque française pub_catalogue_belford.indd 1 24/10/2012 09:47:43 Kōji Wakamatsu (1936-2012) « Lorsque dans les années 2000, les films de Kōji Wakamatsu se remirent à circuler, nous découvrîmes des images d’une pureté bouleversante : une femme nue crucifiée devant le mont Fuji et un homme en pleurs à ses pieds, une vierge éclatant de rire sous le soleil, des amants révolutionnaires dont l’orgasme embrasait Tokyo ; et des jaillissements écarlates de jouissance et de violence et des monochromes bleus, fragiles souvenirs du paradis perdu. Kōji Wakamatsu donnait une voix aux étudiants japonais, mais plus encore à tous les proscrits et les discriminés : les sans-abri de Tokyo, les combattants palestiniens, les adolescents assassins, rendus fous par une société aliénante, et les femmes qu’il désignait, de façon définitive, comme les prolétaires d’une classe masculine féodale et cruelle. Même dans les copies sans sous-titres des Anges violés et Shojo Geba Geba, nous comprenions tout : l’amour fou et la révolution, la haine du pouvoir et l’apologie du plaisir et surtout le romantisme d’une jeunesse prête à tout sacrifier pour son idéal. -

The Final Girl in 1980’S Slasher Films and Halloween (2018) As a Representation of Ideals and Social Issues in 1980S’ America As Well As Contemporary America

Lindved 1 Martin Lindved Anne Bettina Pedersen Engelsk Almen 1 June 2020 Could it be that One Monster has created Another? –The Final Girl in 1980’s Slasher Films and Halloween (2018) as a Representation of Ideals and Social Issues in 1980s’ America as well as Contemporary America. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................2 The Reagan Era in Films of the 1980s ..................................................................................5 The Origin and History of the Slasher Film ........................................................................9 The Making of Halloween ...................................................................................................12 Definition of the Slasher Film .............................................................................................13 The Final Girl as a Male Surrogate ....................................................................................18 The Final Girl as a Feminist Icon .......................................................................................20 ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................................24 The Final Girls of the 1980s’ Slasher Films .................................................24 Final Girls from Halloween ...........................................................................25 Laurie .........................................................................................26 -

Thesis Final

Women in Slashers Then and Now: Survival, Trauma, and the Diminishing Power of the Close-Up by Shyla Fairfax A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Post Doctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Film Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014 Shyla Fairfax Abstract This thesis will reconsider the role of the Final Girl in slasher cinema throughout time, disproving popular notions of her as either a teenage boy incarnate or a triumphant heroine. Instead, an examination of her facial close-ups will make evident that despite her ability to survive, the formal structure of the film emphasizes her ultimate destruction, positioning her instead as a traumatized survivor, specifically of male violence. My research will therefore use close film analysis and feminist film theory to ask how the close-ups develop character as well as narrative, what significance they hold in relation to the structure of the slasher, and most importantly, how they both speak to and challenge gender stereotypes. My methodology will include the comparative analysis of older films to their recent remakes. ii iii Acknowledgements This thesis has been made possible thanks to the excellent guidance of my thesis supervisor, Andre Loiselle. I would also like to note my appreciation for all the support I received throughout this process from my loved ones - my mother, my grandmother, my fiance, and my in-laws. Lastly, I would like to thank my thesis examiners, Charles O’Brien and Ummni Khan, as well as the entire Film Studies faculty who essentially taught me everything I know about cinema.