Navigating Caribbean and Pacific Island Literatures / Elizabeth M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin America and Caribbean Region LIST of ACRONYMS

Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development in Latin America and Caribbean Region LIST OF ACRONYMS ALBA Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas IPs Industrial Parks BIDC Barbados Investment and Development INTI National Institute of Industrial Corperation Technologies (Argentina) BRICS Brazil, Russian Federation, India, China ISID Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial and South Africa („emerging economies“) Development CAF Development Bank for Latin America ITPOs Investment and Technology Promotion CAIME High Level Centre for Research, Offices Training and Certification of Production LATU Technological Laboratory of Uruguay (Uruguayan Project) MERCOSUR Southern Common Market CAN Andean Community MoU Memorandum of Understanding CARICOM Caribbean Community ODS Ozone Depleting Substances CELAC Community of Latin American and OESC Organization of Eastern Caribbean States Caribbean States OFID OPEC Fund for International Development CFCs Chloro-Fluoro-Carbons PCBs Poly-Chlorinated Biphenyls CIU Uruguayan Chamber of Industries POPs Persistent Organic Pollutants CNI National Confederation of Brazil PPPs Public Private Partnerships COPEI Peruvian Committee on Small Industry RO Regional Office ECLAC Economic Commission for Latin America SDGs Sustainable Development Goals EU European Union SELA Latin American Economic System FAO Food and Agriculture Organization (UN SEZs Special Economic Zones System) SICA Central American Integration System GEF Global Environmental Facility SMEs Small and Medium-sized Enterprises GNIC Great Nicaraguan Interoceanic -

African Traditional Plant Knowledge in the Circum-Caribbean Region

Journal of Ethnobiology 23(2): 167-185 Fall/Winter 2003 AFRICAN TRADITIONAL PLANT KNOWLEDGE IN THE CIRCUM-CARIBBEAN REGION JUDITH A. CARNEY Department of Geography, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095 ABSTRACT.—The African diaspora to the Americas was one of plants as well as people. European slavers provisioned their human cargoes with African and other Old World useful plants, which enabled their enslaved work force and free ma- roons to establish them in their gardens. Africans were additionally familiar with many Asian plants from earlier crop exchanges with the Indian subcontinent. Their efforts established these plants in the contemporary Caribbean plant corpus. The recognition of pantropical genera of value for food, medicine, and in the practice of syncretic religions also appears to have played an important role in survival, as they share similar uses among black populations in the Caribbean as well as tropical Africa. This paper, which focuses on the plants of the Old World tropics that became established with slavery in the Caribbean, seeks to illuminate the botanical legacy of Africans in the circum-Caribbean region. Key words: African diaspora, Caribbean, ethnobotany, slaves, plant introductions. RESUME.—La diaspora africaine aux Ameriques ne s'est pas limitee aux person- nes, elle a egalement affecte les plantes. Les traiteurs d'esclaves ajoutaient a leur cargaison humaine des plantes exploitables dAfrique et du vieux monde pour les faire cultiver dans leurs jardins par les esclaves ou les marrons libres. En outre les Africains connaissaient beaucoup de plantes dAsie grace a de precedents echanges de cultures avec le sous-continent indien. -

Country of Citizenship Active Exchange Visitors in 2017

Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 Active Exchange Visitors Country of Citizenship in 2017 AFGHANISTAN 418 ALBANIA 460 ALGERIA 316 ANDORRA 16 ANGOLA 70 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 29 ARGENTINA 8,428 ARMENIA 325 ARUBA 1 ASHMORE AND CARTIER ISLANDS 1 AUSTRALIA 7,133 AUSTRIA 3,278 AZERBAIJAN 434 BAHAMAS, THE 87 BAHRAIN 135 BANGLADESH 514 BARBADOS 58 BASSAS DA INDIA 1 BELARUS 776 BELGIUM 1,938 BELIZE 55 BENIN 61 BERMUDA 14 BHUTAN 63 BOLIVIA 535 BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 728 BOTSWANA 158 BRAZIL 19,231 BRITISH VIRGIN ISLANDS 3 BRUNEI 44 BULGARIA 4,996 BURKINA FASO 79 BURMA 348 BURUNDI 32 CAMBODIA 258 CAMEROON 263 CANADA 9,638 CAPE VERDE 16 CAYMAN ISLANDS 1 CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC 27 CHAD 32 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 CHILE 3,284 CHINA 70,240 CHRISTMAS ISLAND 2 CLIPPERTON ISLAND 1 COCOS (KEELING) ISLANDS 3 COLOMBIA 9,749 COMOROS 7 CONGO (BRAZZAVILLE) 37 CONGO (KINSHASA) 95 COSTA RICA 1,424 COTE D'IVOIRE 142 CROATIA 1,119 CUBA 140 CYPRUS 175 CZECH REPUBLIC 4,048 DENMARK 3,707 DJIBOUTI 28 DOMINICA 23 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 4,170 ECUADOR 2,803 EGYPT 2,593 EL SALVADOR 463 EQUATORIAL GUINEA 9 ERITREA 10 ESTONIA 601 ETHIOPIA 395 FIJI 88 FINLAND 1,814 FRANCE 21,242 FRENCH GUIANA 1 FRENCH POLYNESIA 25 GABON 19 GAMBIA, THE 32 GAZA STRIP 104 GEORGIA 555 GERMANY 32,636 GHANA 686 GIBRALTAR 25 GREECE 1,295 GREENLAND 1 GRENADA 60 GUATEMALA 361 GUINEA 40 Total Number of Active Exchange Visitors by Country of Citizenship in Calendar Year 2017 GUINEA‐BISSAU -

RBH Cocktail Menu 6 3 20.Indd

Crafted Cocktails Local Brews RBH MAI TAI 17 LONGBOARD 9 Bacardi Light Rum Lager, Kona Brew Orange Curacao HANALEI ISLAND IPA 9 Lemon Juice Kona Brewing Orgeat Syrup FIRE ROCK 9 ROSE ALL DAY 19 Pale Ale, Kona Brew Grandin Brut Rose BIG WAVE 9 Cîroc Vodka Golden Ale, Kona Brew Aperol Aperitivo WAILUA 9 Strawberry puree, mint Sweet n Sour Wheat Ale, Kona Brew CASTAWAY 9 SPIKED MANGO 18 IPA, Kona Brew Patron Reposado Mango BIKINI BLONDE 9 Fresh Lime Lager, Maui Brew BEACH HOUSE TONIC 19 Bombay Sapphire Gin Wine by the Glass St. Germain Cucumber mint juice BISOL CREDE PROSECCO SUPERIORE, 2017 15/60 Fresh lime juice Fever Tree Tonic Bouquet of wild flowers, followed by fresh apples, pears CHARLES HEIDSIECK BRUT RESERVE,NV,CHAMPAGNE 28/130 KIAWE HEAT 18 Deliciously balanced between the rich white fruits and Del Maguey Vida Mezcal good acidity Grapefruit GRANDIN BRUT ROSE, NV, LOIRE, FRANCE 17/68 Fresh lime juice Elegant, refreshing with hints of red berry fruit Housemade jalapeño syrup Pinch of Hawaiian sea salt CHATEAU GASSIER ESPRIT ROSE, 2017 16/64 Bright red stoned fruit, fresh and balanced Specialty Mocktails ANDRIAN, PINOT GRIGIO, 2017 18/72 Fruity bouquet, ripe honeydew melons and balanced finis LILIKOʻI MOJITO 8 LOVEBLOCK SAUVIGNON BLANC, 2018 17/68 Liliko‘i puree Complex/elegant bouquet of tropical fruits & grassy notes Fresh mint JEAN REVERDY SANCERRE, 2017 19/76 Fresh lime Sparkling water Estate grown for 10 generations in the finest district of the Loire valley NAʻĀLEHU FRUIT STAND 9 LES TOURELLES CHARDONNAY, PREMIER CRU 22/88 Mango -

Economic Commission for Latin America and The

110 100 90 80 ° ° ° ° ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR UNITED STATES OF AMERICA LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN 30° 30° Nassau Gulf of Mexico BAHAMAS La Habana Turks and ATLANTIC OCEAN CUBA Caicos Is. DOMINICAN co MEXICO i Is. REPUBLIC R gin to ir rgin I Cayman Is. r V Vi s. e S ish HAITI u it Mexico Kingston P U r P B 20 20° S ANTIGUA AND ° o a r JAMAICA t n BARBUDA BELIZE - SAINT KITTS a to Montserrat Belmopan u AND NEVIS D -P o Guadeloupe r m HONDURAS Caribbean Sea in in DOMINICA Martinique Guatemala ce go Tegucigalpa SAINT LUCIA GUATEMALA Netherlands BARBADOS NICARAGUA Aruba Antilles R r GRENADA SAINT VINCENT AND o Managua O d THE GRENADINES D a VA lv Port of Spain L a TRINIDAD AND SA n S San José EL Sa PANAMA Caracas TOBAGO COSTA RICA 10 Panamá town 10 ° rge ° VENEZUELA eo Medellín G G SURINAME Santa Fé U Paramaribo de Bogotá Y French Guiana A Cayenne N COLOMBIA A Equator Quito 0 ECUADOR 0 ° Galapagos Is. ° Guayaquil Manaus Belém PERU Recife BRAZIL 10° Lima 10° PACIFIC OCEAN La Paz Brasília BOLIVIA Sucre P 20 AR 20 ° A ° G U São Paulo A Rio de Janeiro Y Isla San Félix Asunción 100° 90° Isla San Ambrosio Members: Antigua and Barbuda Honduras Argentina Italy 30° Bahamas Jamaica Barbados Mexico Islas 30° Belize Netherlands Juan Fernãndez A Santiago N URUGUAY Bolivia Nicaragua ECLAC HQ I Brazil Panama T Buenos Aires Montevideo Canada Paraguay N Chile Peru E Colombia Portugal E G Costa Rica Saint Kitts and Nevis R L Cuba Saint Lucia 40° I A Dominica Saint Vincent and the Dominican Republic Grenadines H 40 Ecuador Spain ° C El Salvador Suriname 40 30 50 France Trinidad and Tobago ° ° ° Grenada United Kingdom l Capital city Guatemala United States of America The boundaries and names shown and the designations used Guyana Uruguay on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance Haiti Venezuela by the United Nations. -

The Foundations of US Air Doctrine

DISCLAIMER This study represents the views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Air University Center for Aerospace Doctrine, Research, and Education (CADRE) or the Department of the Air Force. This manuscript has been reviewed and cleared for public release by security and policy review authorities. iii Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Watts, Barry D. The Foundations ofUS Air Doctrine . "December 1984 ." Bibliography : p. Includes index. 1. United States. Air Force. 2. Aeronautics, Military-United States. 3. Air warfare . I. Title. 11. Title: Foundations of US air doctrine . III. Title: Friction in war. UG633.W34 1984 358.4'00973 84-72550 355' .0215-dc 19 ISBN 1-58566-007-8 First Printing December 1984 Second Printing September 1991 ThirdPrinting July 1993 Fourth Printing May 1996 Fifth Printing January 1997 Sixth Printing June 1998 Seventh Printing July 2000 Eighth Printing June 2001 Ninth Printing September 2001 iv THE AUTHOR s Lieutenant Colonel Barry D. Watts (MA philosophy, University of Pittsburgh; BA mathematics, US Air Force Academy) has been teaching and writing about military theory since he joined the Air Force Academy faculty in 1974 . During the Vietnam War he saw combat with the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing at Ubon, Thailand, completing 100 missions over North Vietnam in June 1968. Subsequently, Lieutenant Colonel Watts flew F-4s from Yokota AB, Japan, and Kadena AB, Okinawa. More recently, he has served as a military assistant to the Director of Net Assessment, Office of the Secretary of Defense, and with the Air Staff's Project CHECKMATE. -

Analysing the Influence of African Dust Storms on the Prevalence of Coral Disease in the Caribbean Sea Using Remote Sensing and Association Rule Data Mining

International Journal of Remote Sensing ISSN: 0143-1161 (Print) 1366-5901 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tres20 Analysing the influence of African dust storms on the prevalence of coral disease in the Caribbean Sea using remote sensing and association rule data mining Heather Hunter & Guido Cervone To cite this article: Heather Hunter & Guido Cervone (2017) Analysing the influence of African dust storms on the prevalence of coral disease in the Caribbean Sea using remote sensing and association rule data mining, International Journal of Remote Sensing, 38:6, 1494-1521 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2016.1277279 Published online: 31 Jan 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tres20 Download by: [Pennsylvania State University] Date: 31 January 2017, At: 12:46 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF REMOTE SENSING, 2017 VOL. 38, NO. 6, 1494–1521 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2016.1277279 Analysing the influence of African dust storms on the prevalence of coral disease in the Caribbean Sea using remote sensing and association rule data mining Heather Hunter a and Guido Cervone b,c aDepartment of Applied Marine Physics, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, Miami, FL, USA; bDepartment of Geography and Institute for CyberScience, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA; cLamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The application of an association rule data mining algorithm is Received 29 July 2016 described to combine remote sensing and in-situ geophysical data Accepted 22 December 2016 to show a relationship between African dust storms, Caribbean climate, and Caribbean coral disease. -

Rural Hysteria: Genre of the Reimagined Past, Spectacle of Aids, and Queer Politics in Diana Lee Inosanto’S the Sensei

RURAL HYSTERIA: GENRE OF THE REIMAGINED PAST, SPECTACLE OF AIDS, AND QUEER POLITICS IN DIANA LEE INOSANTO’S THE SENSEI Kendall Joseph Binder A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2013 Committee: Becca Cragin, Advisor Jeffrey Allan Brown Marilyn Ferris Motz © 2013 Kendall Joseph Binder All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Becca Cragin, Advisor Diana Inosanto reimagines the 1980s AIDS epidemic in her film, The Sensei (2008) and implements cultural issues on rurality, sexuality, and tolerance within the overall narrative structure. Finding it important to use the works of Rick Altman, John G. Cawelti, and Fredric Jameson, I theorize how postmodernism affects film genres and their evolution through pastiche and historical events. Within this genre cycle, The Sensei fits into several other film genre types that include the queer film, AIDS film, and martial arts film. Drawing from the works of Richard Dyer, B. Ruby Rich, Kylo-Patrick Hart, and David West, I place The Sensei into each category to develop thoughts on how hybrid genres work into film creation. Analyzing the works on myths of the small town and rurality, assumptions about queer migration, and stigmatizations about AIDS, I attempt to disprove these myths and assumptions through the works of Bud W. Jerke, Judith Halberstam, Michael Kennedy, and Emily Kazyak. My overall goal is to project social awareness about queer cultural geography, issues with AIDS in rural areas, and the vitalization of anti-bullying issues that have saturated our media landscape within the last two decades using Inosanto’s The Sensei as a vehicle to evoke thought. -

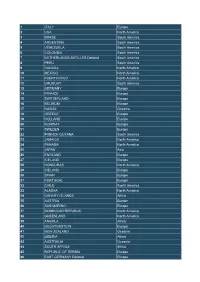

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4

1 ITALY Europe 2 USA North America 3 BRASIL South America 4 ARGENTINA South America 5 VENEZUELA South America 6 COLOMBIA South America 7 NETHERLANDS ANTILLES Deleted South America 8 PERU South America 9 CANADA North America 10 MEXICO North America 11 PUERTO RICO North America 12 URUGUAY South America 13 GERMANY Europe 14 FRANCE Europe 15 SWITZERLAND Europe 16 BELGIUM Europe 17 HAWAII Oceania 18 GREECE Europe 19 HOLLAND Europe 20 NORWAY Europe 21 SWEDEN Europe 22 FRENCH GUYANA South America 23 JAMAICA North America 24 PANAMA North America 25 JAPAN Asia 26 ENGLAND Europe 27 ICELAND Europe 28 HONDURAS North America 29 IRELAND Europe 30 SPAIN Europe 31 PORTUGAL Europe 32 CHILE South America 33 ALASKA North America 34 CANARY ISLANDS Africa 35 AUSTRIA Europe 36 SAN MARINO Europe 37 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC North America 38 GREENLAND North America 39 ANGOLA Africa 40 LIECHTENSTEIN Europe 41 NEW ZEALAND Oceania 42 LIBERIA Africa 43 AUSTRALIA Oceania 44 SOUTH AFRICA Africa 45 REPUBLIC OF SERBIA Europe 46 EAST GERMANY Deleted Europe 47 DENMARK Europe 48 SAUDI ARABIA Asia 49 BALEARIC ISLANDS Europe 50 RUSSIA Europe 51 ANDORA Europe 52 FAROER ISLANDS Europe 53 EL SALVADOR North America 54 LUXEMBOURG Europe 55 GIBRALTAR Europe 56 FINLAND Europe 57 INDIA Asia 58 EAST MALAYSIA Oceania 59 DODECANESE ISLANDS Europe 60 HONG KONG Asia 61 ECUADOR South America 62 GUAM ISLAND Oceania 63 ST HELENA ISLAND Africa 64 SENEGAL Africa 65 SIERRA LEONE Africa 66 MAURITANIA Africa 67 PARAGUAY South America 68 NORTHERN IRELAND Europe 69 COSTA RICA North America 70 AMERICAN -

Allen, Chad (B

Allen, Chad (b. 1974) by Linda Rapp Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2005, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Chad Allen gained fame for his sensitive portrayal of an autistic child on a hit television show, but unlike many child stars, he has successfully made the transition from child actor to adult actor. He has also come out as a gay man and become a vocal advocate for glbtq rights. Chad Allen Lazzari and his twin sister, Charity, were born in Cerritos, California on June 5, 1974 and grew up in the neighboring city of Long Beach. Their mother entered the winsome children in twin contests, and when they had success, considered getting them into show business. Her daughter did not enjoy working before the camera, but her son was a natural and made his first professional appearance in a McDonald's commercial at the age of four. When Allen was six he won a role in the pilot episode for a television series, but the show was not picked up. Two years later he was cast as Tommy Westphall, an autistic child, on the hit drama series St. Elsewhere (1983-1986, 1988). Allen later said that his mother explained that "autistic kids lived in their own world, and I understood that." Allen's performance as Tommy Westphall was extraordinarily affecting and nuanced. It quickly established him as a child actor of unusual sensitivity and talent, one who could hold his own in a strong ensemble cast. The youthful Allen had guest roles on almost a dozen series in the 1980s and played recurring characters on Webster (1985-1986), Our House (1986-1988), and My Two Dads (1989-1990). -

Benito Cereno: an Analytical Reflection on Benito Cereno As a Fictional Narrative Dani Kaiser Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette 4997 English: Capstone English Department 10-1-2015 The Literary Significance of Herman Melville’s Benito Cereno: An Analytical Reflection on Benito Cereno as a Fictional Narrative Dani Kaiser Marquette University This project was created for a section of ENGL 4997: Capstone devoted to the life and work of Herman Melville. The Literary Significance of Herman Melville’s Benito Cereno: An Analytical Reflection on Benito Cereno as a Fictional Narrative by Dani Kaiser Abstract: In Herman Melville’s Benito Cereno (1855), Captain Amasa Delano discovers a distressed slave ship in need of aid, only to later find out that his perception of the dire situation was completely incorrect. Melville’s novella is derived from Delano’s nonfiction account of the experience, titled Narrative of Voyages and Travels in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres (1817). This paper focuses on three questions that demonstrate why Melville wrote a novella almost completely derived from a nonfiction account of the events aboard the ship. In order to understand why Melville’s novella is powerful, one must ask, as an overarching question why he wrote it, and, more specifically, what Melville was attempting to communicate to his American readership by writing the novella. Studying what Melville changed from the nonfiction account is important in wholly understanding Melville’s intentions in Benito Cereno. This ultimately goes to show that fictional narratives can be as effective as nonfiction, if not more influential in illuminating complex realities that are likely outside of one’s limited perception. Keywords: Herman Melville, Benito Cereno, Amasa Delano, slavery, African American In Herman Melville’s Benito Cereno (1855), Captain Amasa Delano discovers a distressed slave ship in need of aid, only to later find out that his perception of the dire situation was completely incorrect. -

Ngā Ariki Kaipūtahi and the Mangatū Lands

Wai 814, #P21 Wai 1489, #A22 Ngā Ariki Kaipūtahi and the Mangatū Lands 28 May 2018 Anthony Pātete A report commissioned by the Crown Forestry Rental Trust for the Waitangi Tribunal Mangatū Remedies district inquiry Ngā Ariki Kaipūtahi and the Mangatū Lands, May 2018 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Summary of the findings of the Mangatū Remedies Inquiry ................................................. 5 The identity of Ngā Ariki Kaipūtahi .......................................................................................... 6 Whakapapa ............................................................................................................................. 6 Protest ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Organisation ........................................................................................................................... 9 The rohe of Ngā Ariki Kaipūtahi ............................................................................................. 13 Customary interests of Ngā Ariki Kaipūtahi ........................................................................... 17 Comment on land block interests ......................................................................................... 20 Impact on Ngā Ariki Kaipūtahi...............................................................................................