Confucius Crosses the South Seas Henri Chambert-Loir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Literature from the Chinese Diaspora in Indonesia

CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE FROM THE CHINESE 'DIASPORA' IN INDONESIA Pamela Allen (University of Tasmania) Since the fall of Suharto a number of Chinese-Indonesian writers have begun to write as Chinese-Indonesians, some using their Chinese names, some writing in Mandarin. New literary activities include the gathering, publishing and translating (from Mandarin) of short stories and poetry by Chinese-Indonesians. Pribumi Indonesians too have privileged Chinese ethnicity in their works in new and compelling ways. To date little of this new Chinese-Indonesian literary activity has been documented or evaluated in English. This paper begins to fill that gap by examining the ways in which recent literary works by and about Chinese-Indonesians give expression to their ethnic identity. Introduction Since colonial times the Chinese have been subjected to othering in Indonesia on account of their cultural and religious difference, on account of their perceived dominance in the nation’s economy and (paradoxically, as this seems to contradict that economic - 1 - dominance) on account of their purported complicity with Communism. The first outbreak of racial violence towards the Chinese, engineered by the Dutch United East Indies Company, was in Batavia in 1740.1 The perceived hybridity of peranakan Chinese (those born in Indonesia) was encapsulated in the appellation used to describe them in pre-Independence Java: Cina wurung, londa durung, Jawa tanggung (‘no longer a Chinese, not yet a Dutchman, a half- baked Javanese’).2 ‘The Chinese are everywhere -

An Annotated List of Chinese-Malay Publications Compiled by Tom

THE “KWEE COLLECTION” AT THE FISHER LIBRARY (UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY) An annotated list of Chinese-Malay publications Compiled by Tom Hoogervorst on the basis of library research carried out in October 2019, with financial support from a Sydney Southeast Asia Centre mobility grant CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 3 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 6 1. Poetry ................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1. Han Bing Hwie ................................................................................................................ 7 1.2. “J.S.H.” ............................................................................................................................ 7 1.3. Jap King Hong ................................................................................................................. 7 1.4. Kwee Tek Hoay ............................................................................................................... 8 1.5. “Merk Tek Liong & Co” ................................................................................................. 8 2. Original Fiction ................................................................................................................. 9 2.1. Kwee Seng Tjoan ............................................................................................................ -

Bangsawan Prampoewan Enlightened Peranakan Chinese Women from Early Twentieth Century Java

422 WacanaWacana Vol. Vol.18 No. 18 2No. (2017): 2 (2017) 422-454 Bangsawan prampoewan Enlightened Peranakan Chinese women from early twentieth century Java Didi Kwartanada ABSTRACT The end of the nineteenth century witnessed paradox among the Chinese in colonial Java. On one hand, they were prospering economically, but were nonetheless held in contempt by the Dutch, encountered legal discrimination and faced challenges if they wanted to educate their children in European schools. Their marginal position motivated them do their utmost to become “civilized subjects”, on a par with Europeans, but they were also inspired to reinvent their Chinese identity. This contribution will highlight role played by “enlightened” Chinese, the kaoem moeda bangsa Tjina. Central to this movement were the Chinese girls known to the public as bangsawan prampoewan (the noblewomen), who wrote letters the newspaper and creating a gendered public sphere. They also performed western classical music in public. Considering the inspirational impact of bangsawan prampoewan’s enlightening achievements on non-Chinese women, it is appropriate to include them into the narrative of the history of the nation’s women’s movements. KEYWORDS Chinese; women; modernity; progress; newspapers; Semarang; Surabaya; western classical music; Kartini. Didi Kwartanada studies history of the ethnic Chinese in Indonesia, especially Java. He is currently the Director of the Nation Building Foundation (NABIL) in Jakarta and is preparing a book on the history of Chinese identity cards in Indonesia. His publications include The encyclopedia of Indonesia in the Pacific War (Leiden: Brill, 2009) as co-editor and contributor, and the most recent work Tionghoa dalam keindonesiaan; Peran dan kontribusi bagi pembangunan bangsa (3 vols; Jakarta: Yayasan Nabil, 2016) as managing editor cum contributor. -

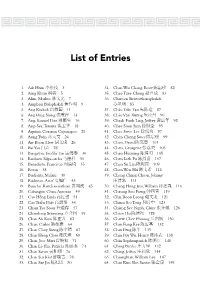

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

Komunitas Tionghoa Di Solo: Dari Terbentuknya Chuan Min Kung Hui Hingga Perkumpulan Masyarakat Surakarta (1932-1959)

Komunitas Tionghoa di Solo: Dari terbentuknya Chuan Min Kung Hui Hingga Perkumpulan Masyarakat Surakarta (1932-1959) SKRIPSI Diajukan Untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Sastra Program Studi Sejarah Disusun Oleh : CHANDRA HALIM 024314004 JURUSAN ILMU SEJARAH FAKULTAS SASTRA UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2008 2 3 4 MOTTO Keinginan tanpa disertai dengan tindakan adalah sia-sia. Sebaliknya ketekunan dan kerja keras akan mendatangkan keberhasilan yang melimpah. (Amsal 13:4) 5 HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Tiada kebahagiaan yang terindah selain mempersembahkan skripsi ini kepada : Thian Yang Maha Kuasa serta Para Buddha Boddhisattva dan dewa dewi semuanya yang berkenan membukakan jalan bagi kelancaran studiku. Papa dan Mama tercinta, serta adik-adikku tersayang yang selalu mendoakan aku untuk keberhasilanku. Om Frananto Hidayat dan keluarga yang berkenan memberikan doa restunya demi keberhasilan studi dan skripsiku. 6 ABSTRAK Komunitas Tionghoa di Solo: Dari terbentuknya Chuan Min Kung Hui hingga Perkumpulan Masyarakat Surakarta (1932-1959) Chandra Halim 024314004 Skripsi ini berjudul “Komunitas Tionghoa di Solo : Dari Terbentuknya Chuan Min Kung Hui Hingga Perkumpulan Masyarakat Surakarta (1932-1959)“. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mendeskripsikan dan menganalisis tiga permasalahan yang diungkapkan, yaitu sejarah masuknya Etnik Tionghoa di Solo, kehidupan berorganisasi Etnik Tionghoa di Solo dan pembentukan organisasi Chuan Min Kung Hui (CMKH) hingga berubah menjadi Perkumpulan Masyarakat Surakarta (PMS). Metode yang digunakan dalam penulisan skripsi ini adalah metode sejarah yang mencakup heuristik, kritik sumber, interpretasi, dan penulisan. Selain itu juga menggunakan metode wawancara sebagai sumber utama, dan studi pustaka sebagai sumber sekunder dengan mencari sumber yang berasal dari buku-buku, koran, dan majalah. Penelitian ini menunjukkan bahwa keberadaan Tionghoa di Solo sudah ada sejak 1740, tepatnya ketika Solo dalam kekuasaan Mataram Islam. -

Kwee Kek Beng (Guo Keming)

Denken over de peranakan identiteit: Kwee Kek Beng (Guo Keming) Que Soei Keng (gepubliceerd in het Hua Yi blad van Maart 2009) seudoniemen: Garem (zout); Thio Boen Hiok. Geboren te Jakarta op 16 P nov 1900 en overleden te Jakarta 31 mei 1975. Gehuwd met Tee Lim Nio. Kwee was publicist en hoofdredacteur van het dagblad Sin Po (1925- 1947). Prominent intellectueel leider van de Chinese gemeenschap in Indonesië en filosoof van de Chinese stroming binnen de Indonesische filosofie. Vader van architect Kwee Hin Goan (Jakarta 4 juni 1932) en journalist-schrijver Xing-hu Kuo (Kwee Hin Houw , Jakarta 12 mei 1938). Opleiding Hollands-Chinese School (HCS) en Hollands- Chinese Kweekschool (HCK) te Jakarta. In 1922 werd hij onderwijzer aan de HCS Tanjakan Empang te Bogor, trad na vier maanden in dienst van Bin Seng (een locaal dagblad van Batavia dat net was opgericht door Tjoe Bou San) en de redactie van het Maleis-Chinese blad Sin Po. Na de dood van Tjoe Bou San in 1925 werd hij hoofdredacteur, een functie die hij tot 1947 zou behouden. Hij vertegenwoordigde evenals zijn voorganger de Chinees nationalistische stroming binnen de Chinese gemeenschap Indonesia Raya en Sin Po (Een bewerking uit de autobiografie “BLOEIENDE BRON, Een architectenleven” door Kwee Hin Goan). In oktober 1910, aan de vooravond van de Chinese revolutie tegen het Manchu- regime, verscheen in toenmalig Batavia een weekblad, “Sin Po” of “Nieuw Blad”. Een jaar later werd het omgezet in een dagblad met Razoux Kuhr, een gewezen Indo ambtenaar (Binnenlands Bestuur), als hoofdredacteur. Sin Po was vervuld van jeugdig enthousiasme en vol vuur voor de revolutionaire beweging in China onder Dr. -

1942 Skripsi

DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PERANAN PERS TIONGHOA PERANAKAN DI SURABAYA DALAM PERGERAKAN NASIONAL 1902 – 1942 SKRIPSI Oleh Saripa Haini Jumita Asmadi NIM. 090110301002 JURUSAN SEJARAH FAKULTAS SASTRA UNIVERSITAS JEMBER 2015 DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PERANAN PERS TIONGHOA PERANAKAN DI SURABAYA DALAM PERGERAKAN NASIONAL 1902 – 1942 SKRIPSI Diajukan guna melengkapi tugas akhir dan memenuhi salah satu syarat untuk menyelesaikan program Studi pada Jurusan Sejarah (S1) dan mencapai gelar Sarjana Sastra. Oleh Saripa Haini Jumita Asmadi NIM. 090110301002 JURUSAN SEJARAH FAKULTAS SASTRA UNIVERSITAS JEMBER 2015 DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini: Nama : Saripa Haini Jumita Asmadi NIM : 090110301002 Menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa karya ilmiah yang berjudul “Peranan Pers Tionghoan Peranakan di Surabaya dalam Pergerakan Nasional 1902-1942” adalah benar-benar hasil karya sendiri, kecuali kutipan yang sudah saya sebutkan sumbernya, belum pernah diajukan pada institusi mana pun dan bukan karya jiplakan. Saya bertanggung jawab atas keabsahan dan kebenaran isinya sesuai dengan sikap ilmiah yang harus dijunjung tinggi. Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat dengan sebenarnya, tanpa ada tekanan dan paksaan dari pihak mana pun serta bersedia mendapat sanksi akademik apabila ternyata di kemudian hari pernyataan ini tidak benar. Jember, 12 Februari 2015 Yang menyatakan, Saripa Haini -

Liem Thian Joe's Unpublished History of Kian Gwan

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 27, No.2, September 1989 Liem Thian Joe's Unpublished History of Kian Gwan Charles A. COPPEL* Studies on the role of the overseas Chinese sue the talent for writing which was already in the economies of Southeast Asia are rare evident in his schoolwork. A short ex enough, despite their generally acknowledged perience as a trader in Ngadiredjo soon con importance. This has been particularly true vinced him, however, that he should seek his of Indonesia, and consequently it is a matter livelihood as a writer. of some interest to discover an unpublished His career in journalism seems to have history of Kian Gwan (Oei Tiong Ham Con begun in the 1920's when he joined the staff of cern), the biggest and longest-lasting Chinese the Semarang peranakan Chinese daily, Warna business of all in Indonesia. Further interest Warla (although there is some suggestion that is aroused by the fact that the manuscript was he also contributed to the Jakarta daily, Per written by the late Liem Thian Joe, the well niagaan, at this time). In the early 1930's, he known Semarang journalist and historian. moved from Warna Warta to edit the Semarang This combination gives us promise of insights daily, Djawa Tengah (and its sister monthly into the firm itself, the Oei family which Djawa Tengah Review). In later years he established it and built it up, and the history of was also a regular contributor to the weekly the Chinese of Semarang where its original edition of the Jakarta newspaper, Sin PO.2) office was founded. -

M. Cohen on the Origin of the Komedie Stamboelpopular Culture, Colonial Society, and the Parsi Theatre Movement

M. Cohen On the origin of the Komedie StamboelPopular culture, colonial society, and the Parsi theatre movement In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 157 (2001), no: 2, Leiden, 313-357 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/10/2021 12:19:15AM via free access MATTHEW ISAAC COHEN On the Origin of the Komedie Stamboel Popular Culture, Colonial Society, and the Parsi Theatre Movement Introduction . The Komedie Stamboel, also known as the Malay Opera, occupies a prom- inent place in Indonesia's cultural history.1 lts emergence in 1891 has been characterized as a 'landmark' in the development of modern popular theatre (Teeuw 1979:207). The theatre later contributed greatly to the birth of Indo- nesian contemporary theatre and film2 and played a formative role in mod- ern political discourse and representation (see Anderson 1996:36-7). The Komedie Stamboel has been celebrated as one of the most significant 'artistic achievements' of the Eurasian population of colonial Java (see Van der Veur 1968a), but also damned for its deleterious influence on Java's classical and 1 This article was written while a postdoctoral research fellow at the International Institute for Asian Studies (DAS). It was presented in part as lectures at KAS and the Fifth International Humanities Symposium, Gadjah Mada University, in 1998.1 would like to thank all the particip- ants in the research seminar, 'Popular theatres of Indonesia', Department of Southeast Asian and Oceanic Languages and Cultures, Leiden University, where I developed some of the ideas pre- sented here, as well as Kathryn Hansen, Rakesh Solomon, Catherine Diamond, Surapone Virulrak, Hanne de Bruin, and two anonymous BKI reviewers for their comments. -

Moral Is Political Notions of Ideal Citizenship in Lie Kim Hok’S Hikajat Khonghoetjoe

WacanaEvi Sutrisno Vol. 18 No., Moral 1 (2017): is political 183-215 183 Moral is political Notions of ideal citizenship in Lie Kim Hok’s Hikajat Khonghoetjoe EVI SUTRISNO ABSTRACT This paper argues that the Hikajat Khonghoetjoe (The life story of Confucius), written by Lie Kim Hok in 1897, is a medium to propose modern ideas of flexible subjectivity, cosmopolitanism, active citizenship and the concepts of good governance to the Chinese Peranakans who experienced political and racial discrimination under Dutch colonization. Using the figure of Confucius, Lie aimed to cultivate virtuous subjects who apply their faith and morality in political sphere. He intended to raise political awareness and rights among the Chinese as colonial subjects and to valorize their bargaining power with the Dutch colonial government. By introducing Confucianism, Lie proposed that the Chinese reconnect themselves with China as an alternative patronage which could subvert White supremacy. Instead of using sources in Chinese, Lie translated the biography of Confucius from the European texts. In crafting his story, Lie applied conglomerate authorship, a technique commonly practised by Malay authors. It allowed him to select, combine and appropriate the source texts. To justify that Confucius' virtue and his teaching were superb and are applicable to contemporary life, Lie borrowed and emphasized European writers’ high appraisal of Confucianism, instead of using his own arguments and opinions. I call this writing technique “indirect agency”. KEYWORDS Confucianism; the biography of Confucius; Chinese-Indonesians; Lie Kim Hok; active citizenship; cosmopolitanism. Evi Sutrisno is a PhD student in Anthropology, the University of Washington, Seattle. Her research investigates the foundation and development of the Confucian religion (agama Khonghucu) in Indonesia from the 1890s to 2010. -

1 Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I Have Been

Chapter 1 Introduction As a Chinese Buddhist in Malaysia, I have been unconsciously entangled in a historical process of the making of modern Buddhism. There was a Chinese temple beside my house in Penang, Malaysia. The main deity was likely a deified imperial court officer, though no historical record documented his origin. A mosque serenely resided along the main street approximately 50 meters from my house. At the end of the street was a Hindu temple decorated with colorful statues. Less than five minutes’ walk from my house was a Buddhist association in a two-storey terrace. During my childhood, the Chinese temple was a playground. My friends and I respected the deities worshipped there but sometimes innocently stole sweets and fruits donated by worshippers as offerings. Each year, three major religious events were organized by the temple committee: the end of the first lunar month marked the spring celebration of a deity in the temple; the seventh lunar month was the Hungry Ghost Festival; and the eighth month honored, She Fu Da Ren, the temple deity’s birthday. The temple was busy throughout the year. Neighbors gathered there to chat about national politics and local gossip. The traditional Chinese temple was thus deeply rooted in the community. In terms of religious intimacy with different nearby temples, the Chinese temple ranked first, followed by the Hindu temple and finally, the mosque, which had a psychological distant demarcated by racial boundaries. I accompanied my mother several times to the Hindu temple. Once, I asked her why she prayed to a Hindu deity. -

UM2/10, Friday, 26 February 2010 Published by ASIC ASIC Gazette

= Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. UM2/10, Friday, 26 February 2010 Published by ASIC ASIC Gazette Contents Unclaimed consideration for compulsory acquisition - S668A Corporations Act RIGHTS OF REVIEW Persons affected by certain decisions made by ASIC under the Corporations Act 2001 and the other legislation administered by ASIC may have rights of review. ASIC has published Regulatory Guide 57 Notification of rights of review (RG57) and Information Sheet ASIC decisions – your rights (INFO 9) to assist you to determine whether you have a right of review. You can obtain a copy of these documents from the ASIC Digest, the ASIC website at www.asic.gov.au or from the Administrative Law Co-ordinator in the ASIC office with which you have been dealing. ISSN 1445-6060 (Online version) Available from www.asic.gov.au ISSN 1445-6079 (CD-ROM version) Email [email protected] © Commonwealth of Australia, 2010 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all rights are reserved. Requests for authorisation to reproduce, publish or communicate this work should be made to: Gazette Publisher, Australian Securities and Investment Commission, GPO Box 9827, Melbourne Vic 3001 ASIC GAZETTE Commonwealth of Australia Gazette UM2/10, Friday, 26 February 2010 Unclaimed consideration for compulsory acquisition Page 2 of 282= Unclaimed consideration for compulsory acquisition - S668A Corporations Act Copies of records of unclaimed consideration in respect of securities, of the following companies, that have been