Visit of Marek Lorenc, Vice Dean of the Faculty of Landscape Engineering and Geodesy, Agricultural University of Wroclaw, to T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stannaries

THE STANNARIES A STUDY OF THE MEDIEVAL TIN MINERS OF CORNWALL AND DEVON G. R. LEWIS First published 1908 PREFACE THEfollowing monograph, the outcome of a thesis for an under- graduate course at Harvard University, is the result of three years' investigation, one in this country and two in England, - for the most part in London, where nearly all the documentary material relating to the subject is to be found. For facilitating with ready courtesy my access to this material I am greatly indebted to the officials of the 0 GEORGE RANDALL LEWIS British Museum, the Public Record Office, and the Duchy of Corn- wall Office. I desire also to acknowledge gratefully the assistance of Dr. G. W. Prothero, Mr. Hubert Hall, and Mr. George Unwin. My thanks are especially due to Professor Edwin F. Gay of Harvard University, under whose supervision my work has been done. HOUGHTON,M~CHIGAN, November, 1907. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION purpose of the essay. Reasons for choice of subject. Sources of informa- tion. Plan of treatment . xiii CHAPTER I Nature of tin ore. Stream tinning in early times. Early methods of searching for ore. Forms assumed by the primitive mines. Drainage and other features of medizval mine economy. Preparation of the ore. Carew's description of the dressing of tin ore. Early smelting furnaces. Advances in mining and smelt- ing in the latter half of the seventeenth century. Preparation of the ore. Use of the steam engine for draining mines. Introduction of blasting. Pit coal smelting. General advance in ore dressing in the eighteenth century. Other improvements. -

Minewater Study

National Rivers Authority (South Western-Region).__ Croftef Minewater Study Final Report CONSULTING ' ENGINEERS;. NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY SOUTH WESTERN REGION SOUTH CROFTY MINEWATER STUDY FINAL REPORT KNIGHT PIESOLD & PARTNERS Kanthack House Station Road September 1994 Ashford Kent 10995\r8065\MC\P JS TN23 1PP ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 125218 r:\10995\f8065\fp.Wp5 National Rivers Authority South Crofty Minewater Study South Western Region Final Report CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY -1- 1. INTRODUCTION 1-1 2. THE SOUTH CROFTY MINE 2-1 2.1 Location____________________________________________________ 2-1 ________2.2 _ Mfning J4istojy_______________________________________ ________2-1. 2.3 Geology 2-1 2.4 Mine Operation 2-2 3. HYDROLOGY 3-1 3.1 Groundwater 3-1 3.2 Surface Water 3-1 3.3 Adit Drainage 3-2 3.3.1 Dolcoath Deep and Penhale Adits 3-3 3.3.2 Shallow/Pool Adit 3-4 3.3.3 Barncoose Adit 3-5 4. MINE DEWATERING 4-1 4.1 Mine Inflows 4-1 4.2 Pumped Outflows 4-2 4.3 Relationship of Rainfall to Pumped Discharge 4-3 4.4 Regional Impact of Dewatering 4-4 4.5 Dewatered Yield 4-5 4.5.1 Void Estimates from Mine Plans 4-5 4.5.2 Void Estimate from Production Tonnages 4-6 5. MINEWATER QUALITY 5-1 5.1 Connate Water 5-2 5.2 South Crofty Discharge 5-3 5.3 Adit Water 5-4 5.4 Acidic Minewater 5-5 Knif»ht Piesold :\10995\r8065\contants.Wp5 (l) consulting enCneers National Rivers Authority South Crofty Minewater Study South Western Region Final Report CONTENTS (continued) Page 6. -

4.0 Appraisal of Special Interest

4.0 APPRAISAL OF SPECIAL INTEREST 4.1 Character Areas Botallack The history and site of Botallack Manor is critical to an understanding of the history and development of the area. It stands at the gateway between the village and the Botallack mines, which underlay the wealth of the manor, and were the reason for the village’s growth. The mines are clearly visible from the manor, which significantly stands on raised ground above the valley to the south. Botallack Manor House remains the single most important building in the area (listed II*). Dated 1665, it may well be earlier in some parts and, indeed, is shown on 19th century maps as larger – there are still 17th century moulded archway stones to be found in the abandoned cottage enclosure south of the manor house. The adjoining long range to the north also has 17th century origins. The complex stands in a yard bounded by a well built wall of dressed stone that forms a strong line along the road. The later detached farm buildings slightly to the east are a good quality 18th/19th century group, and the whole collection points to the high early status of the site, but also to its relative decline from ‘manorial’ centre to just one of the many Boscawen holdings in the area from the early 19th century. To the south of Botallack Manor the village stretches away down the hill. On the skyline to the south is St Just, particularly prominent are the large Methodist chapel and the Church, and there is an optical illusion of Botallack and St Just having no countryside between them, perhaps symbolic of their historical relationship. -

Copyrighted Material

176 Exchange (Penzance), Rail Ale Trail, 114 43, 49 Seven Stones pub (St Index Falmouth Art Gallery, Martin’s), 168 Index 101–102 Skinner’s Brewery A Foundry Gallery (Truro), 138 Abbey Gardens (Tresco), 167 (St Ives), 48 Barton Farm Museum Accommodations, 7, 167 Gallery Tresco (New (Lostwithiel), 149 in Bodmin, 95 Gimsby), 167 Beaches, 66–71, 159, 160, on Bryher, 168 Goldfish (Penzance), 49 164, 166, 167 in Bude, 98–99 Great Atlantic Gallery Beacon Farm, 81 in Falmouth, 102, 103 (St Just), 45 Beady Pool (St Agnes), 168 in Fowey, 106, 107 Hayle Gallery, 48 Bedruthan Steps, 15, 122 helpful websites, 25 Leach Pottery, 47, 49 Betjeman, Sir John, 77, 109, in Launceston, 110–111 Little Picture Gallery 118, 147 in Looe, 115 (Mousehole), 43 Bicycling, 74–75 in Lostwithiel, 119 Market House Gallery Camel Trail, 3, 15, 74, in Newquay, 122–123 (Marazion), 48 84–85, 93, 94, 126 in Padstow, 126 Newlyn Art Gallery, Cardinham Woods in Penzance, 130–131 43, 49 (Bodmin), 94 in St Ives, 135–136 Out of the Blue (Maraz- Clay Trails, 75 self-catering, 25 ion), 48 Coast-to-Coast Trail, in Truro, 139–140 Over the Moon Gallery 86–87, 138 Active-8 (Liskeard), 90 (St Just), 45 Cornish Way, 75 Airports, 165, 173 Pendeen Pottery & Gal- Mineral Tramways Amusement parks, 36–37 lery (Pendeen), 46 Coast-to-Coast, 74 Ancient Cornwall, 50–55 Penlee House Gallery & National Cycle Route, 75 Animal parks and Museum (Penzance), rentals, 75, 85, 87, sanctuaries 11, 43, 49, 129 165, 173 Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Round House & Capstan tours, 84–87 113 Gallery (Sennen Cove, Birding, -

A Sensory Guide to King Edward

Sensory experiences a sensory guide to Blackberries from the hedgerow, a pasty picnic. King Edward Mine Carn Brea monument, towering engine houses. A buzzards cry, the silence, imagine the constant hammering of the stamps. The granite blocks of the engine houses. Gorse flowers, clean air. A tale of the Bal I used to leave Carwinnen at six o’clock in the morning. It was alright in the summer, but in the winter mornings I was afraid of the dark. When I “ got to Troon the children used to come along from Welcome to King Edward Mine Black Rock and Bolenowe. We used to lead hands King Edward Mine has been an important part of Cornish and sing to keep“ our spirits up. Sometimes when Mining history for the last 200 years. It began as a copper mine, we got to the Bal the water was frozen over. I have then it turned to tin. Many men, women and children from cried scores of times with wonders in my fingers the surrounding area would have walked to work here every and toes. day, undertaking hard physical work all day long to mine and process the ore from the ground into precious Cornish tin. A Dolcoath Bal Maiden 1870, Mrs Dalley. The site later became home to the Camborne School of Mines. This internationally renowned institution taught students from all around the world the ways of mining. These students then took the skills learnt here in Cornwall across the globe. www.sensorytrust.org.uk The landscape would have Working life Recollections of the Red River Tin looked like this.. -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13Ra NOVEMBER 1973 13529

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13ra NOVEMBER 1973 13529 37, Crescent Road, Cowley; 57, Bailey Road, Cowley ; 5, APPLICATIONS FOR DISCHARGE Nursery Close, Headington, and 54, St. Leonards Road, Headington all in the county of Oxford, PAINTER and LAMBERT, Patricia Diana (married woman) of 85A, Hurst DECORATOR. Court—OXFORD. No. of Matter— Grove, Queen's Park, Bedford, in the county of Bedford, 30 of 1973. Date of Order—29th Oct., 1973. Date of who formerly resided at and carried on business at Rose- Filing Petition—16th Aug., 1973. mary Cottage, Pertenhall in the county of Bedford under the style of "Lambert Construction", BUILDERS and CURRIE, Charles, of 74A, Elm Grove, Southsea, Hamp- CONTRACTORS. Court—BEDFORD. No. of Matter shire, unemployed salesman. Court—PORTSMOUTH. —12 of 1966. Day Fixed for Hearing—12th Dec., 1973. No. of Matter—39 of 1973. Date of Order—6th Nov., 10.30 a.m. Place—3rd Floor, Palace Chambers, Silver 1973. Date of Filing Petition—6th Nov., 1973. Street, Bedford. WOOLLFORD, Gordon Bruce, of 40, Pondmoor Road, CUBONI, Luigi, of 62, Anderton Park Road, Moseley, Easthampstead, Bracknell in the county of Berkshire, Birmingham, 13, in the county of Warwick, Chef lately TAXI DRIVER, from 2, Alexander Walk, Easthampstead, carrying on business in partnership with another as Bracknell, Berks., carrying on business in the style of RESTAURATEURS under the style of "Da Luigi G. B. Woollford Car Hire (a firm). Court—READING. Restauarant" at 49 Lichfield Road, Aston, Birmingham, No. of Matter—64 of 1973. Date of Order—5th Nov., aforesaid and formerly carrying on business as a RES- 1973. -

The Cornish Mining World Heritage Events Programme

Celebrating ten years of global recognition for Cornwall & west Devon’s mining heritage Events programme Eighty performances in over fifty venues across the ten World Heritage Site areas www.cornishmining.org.uk n July 2006, the Cornwall and west Devon Mining Landscape was added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites. To celebrate the 10th Ianniversary of this remarkable achievement in 2016, the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site Partnership has commissioned an exciting summer-long set of inspirational events and experiences for a Tinth Anniversary programme. Every one of the ten areas of the UK’s largest World Heritage Site will host a wide variety of events that focus on Cornwall and west Devon’s world changing industrial innovations. Something for everyone to enjoy! Information on the major events touring the World Heritage Site areas can be found in this leaflet, but for other local events and the latest news see our website www.cornish-mining.org.uk/news/tinth- anniversary-events-update Man Engine Double-Decker World Record Pasty Levantosaur Three Cornishmen Volvo CE Something BIG will be steaming through Kernow this summer... Living proof that Cornwall is still home to world class engineering! Over 10m high, the largest mechanical puppet ever made in the UK will steam the length of the Cornish Mining Landscape over the course of two weeks with celebratory events at each point on his pilgrimage. No-one but his creators knows what he looks like - come and meet him for yourself and be a part of his ‘transformation’: THE BIG REVEAL! -

Gently Sloping

LOCAL LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT – NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING Carn Brea – Gently Sloping CHARACTER TYPE: DATE OF ASSESSMENT: T Gently Sloping 22/02/2021 t PARISH : Carn Brea ASSESSOR :Florence h MacDonald e Character Landscape reference guide Your landscape description Attribute Record your descriptive information for each heading Topography What is the shape of the land? - flat, shallow, steep, The land undulates gently in a broad basin between the steep slopes leading to Carn Brea and Four Lanes uniform, undulating, upland, ridge, plateau respectively. Photo 1. and drainage Is there any water present? - estuary, river, fast flowing stream, babbling brook, spring, reservoir, pond, Some water gathers in rainier weather with large puddles and marshy areas. The source of the Red River, which marsh follows the boundary of the Parish, is adjacent to Bolenowe.There are lots of gullies present along Cornish hedges that were used to manage the drainage of fields. Photo 2, 3 and 4. Near the flowing water is also more woodland which forms part of the county wildlife site Newton Moor. At the edge of the Parish boundaries there are also flood zones near rivers, particularly on the western side. see: Supporting documents/Appendices of maps/ 5. Flood zones 2&3. Supporting info OS Map; Cornwall Council mapping; aerial photographs Biodiversity What elements of the character could support There is a lot of natural coverage consisting of ferns, bracken, pockets of trees, with established Cornish hedges protected species (guidance from Cornwall Wildlife Trust providing the majority of field boundaries, interspersed with outcrops of granite. These are surrounded by/covered CWT) with bracken, blackberries, brambles, and heather. -

A Unique Opportunity for Copper, Tin and Lithium in Cornwall

A unique opportunity for copper, tin and lithium in Cornwall All information ©Cornish Metals Inc. All Rights Reserved. 1 Cornish Metals Inc Corporate Presentation Disclaimer This presentation may contain forward-looking statements which involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which may cause the actual results, performance, or achievements to be materially different from any future results, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Forward looking statements may include statements regarding exploration results and budgets, resource estimates, work programs, strategic plans, market price of metals, or other statements that are not statements of fact. Although the expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable, there is no assurance that such expectations will prove to have been correct. Various factors that may affect future results include, but are not limited to: fluctuations in market prices of metals, foreign currency exchange fluctuations, risks relating to exploration, including resource estimation and costs and timing of commercial production, requirements for additional financing, political and regulatory risks. Accordingly, undue reliance should not be placed on forward-looking statements. All technical information contained within this presentation has been reviewed and approved for disclosure by Owen Mihalop, (MCSM, BSc (Hons), MSc, FGS, MIMMM, CEng), Cornish Metals’ Qualified Person as designated by NI 43-101. Readers are further referred -

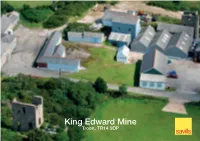

King Edward Mine, Troon, TR14 9DP

King Edward Mine Troon, TR14 9DP King Edward Mine, Troon, TR14 9DP Heritage Workshops for growing businesses Imagine working in an affordable rural environment that inspires creativity, forward thinking and business growth. Imagine having newly created office space in Grade II* Listed historic buildings sympathetically conserved and refurbished to the highest standards possible. Nine new workspace units at King Edward Mine, near Troon, West Cornwall have been created towards the rear of the site in the former Count House and Carpenters’ Shop. The units are of varying sizes with tenants already occupying some of the units. King Edward Mine, the former home of Camborne School of Mines, was acquired by Cornwall Council in 2009 and is substantially leased to a local charity to run as a mining heritage attraction. The site is recognised as having Outstanding Universal Value as the oldest, best preserved mine within the Cornish Mining World Heritage Site (WHS) for the pre-1920 period. The entire complex is within the WHS and includes sixteen Grade II* Listed buildings, the Grade II Listed South Condurrow Stamps Engine House and benefits from the Great Flat Lode mineral tramway multi-use trail passing through the site. The development has been made possible thanks to a grant of over a million pounds from the ERDF Convergence Programme and funding from Cornwall Council. Using local expertise and traditional building techniques, both buildings have been comprehensively restored to offer a range of accommodation Terms of Letting and facilities. All units are offered on new leases for a minimum term of 3 years. UNIT SQ M RENT PER ANNUM £ These workshops are the first phase of two major capital Rent will be payable monthly in advance and is inclusive of developments at King Edward Mine. -

John Harris Society Newsletter

THE John Harris Newsletter Society No 60 Summer 2017 John Harris: miner, poet, preacher 1820-1884 This classic and beautiful picture of Wheal Coates, on Cornwall’s north coast between Porthtowan and St Agnes, taken by Tony Kent, of Truro, has been used on the flyer being sent to organisations and individuals worldwide to highlight the bi-centenary festival of John Harris in 2020. We are extremely grateful to Tony for allowing us to use this photograph. See page 3 for a picture of the complete flyer. JHS 2 Annual general meeting – 18 February ’17 Thirty four people, including descendants of William John Bennetts, attended the meeting and stayed for David Thomas‘ presentation of ‗The William John Ben- netts Photographic Archive’ (covering the Camborne district in the Victorian pe- riod). We are grateful to David and to those who provided and served the refresh- ments as they concluded a very pleasant, interesting and informative afternoon. At the meeting, we welcomed three new members to the Society and I am de- lighted to say that Mr Peter Bickford-Smith, of Chynhale, was appointed as our President for a four-year period which will give continuity through our 2020 Bi- Centenary Festival. Further information about Peter is included later in this news- Paul Langford letter. During the business meeting, thanks were expressed to Caroline Palmer for her maintenance of the Facebook page and to Diane Hodnett for keeping the website up to date. The fact that we are not a wealthy Society was shown by the financial statement that showed a balance at 31 December 2016 of £726.93. -

![[Cornwall.] 698 (Post 0 Ffic:E](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4848/cornwall-698-post-0-ffic-e-1224848.webp)

[Cornwall.] 698 (Post 0 Ffic:E

• [CORNWALL.] 698 (POST 0 FFIC:E ha-ving changed into tin, one is now being developed for WliEA.L COMFORD MINE copper. There are three main cross-courses. The company is on the limited liability system, and consists of 25,000 £1 Is in the parish of Gwennap, Duchy of Cornwall, and shares. mining district of Gwennap. It is situated 2 miles from Redruth. A branch line of the West Cornwall comes into Secretary~ Consulting Engineer, T. Currie Gregory, 62 the centre of the mine, by which all produce can be 11ent or St. Vincent street, Gla!!gow material received. The nearest shipping places for ores and Purxers ~Managers, Messrs. Skewis & Bawden, Tavistock machinery are Devoran and Portreath, 6 amJ 5 miles from Resident Agents, Samuel Mayne & Z. J ames the mine. The mine is held under a lea~m for 21 years, granted by Lord Clinton and others. The mine is worked WHEAL BASSET MINE now for tin, it having formerly been a copper mine, from Is in the parish of Illogan, and mining district oz Basset; which produce many dividends were paid. The company is it is situated g miles from the town of Redruth. The on the costbook system, and divided into 5,175 shares. nearest shipping place is at Portreath, 5 miles, and the Purser, John Sambell, Redruth nearest railway station is at Redruth, I~ mile11. The mine is held under a lease for 21 years from 1871, at a royalty of Agent, Peter Phillips, Stithians l-15th, wanted by Gustavus L. Basset Basset, ofTehidypark. WHEAL CONCORD TIN MINE, ST.