Luigi Gentili

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Reflection

VOL.48, NO.2 MAY 2017 Missionary Association of Mary Immaculate Provincial Reflection I am writing this on a 6 hour stopover with two remarkable Missionaries. One at the Hong Kong International Airport was a Spanish sister, Sister Rosario who, after having the privilege of spending after almost 40 years in northern India, a week and a half in the Philippines and and other places beforehand, came to then almost two weeks in Hong Kong/ Guangzhou at the age of 74 years, and China. I say a privilege because I have after 12 years there is going strong, with spent time with Oblates from the a passion for the people and the Lord Chinese. They continued, that although Asia/Oceania region and have visited which is infectious. The other missionary they appreciated the generosity and some of the inspiring places of their is Fr David Ullrich OMI who has spent the charity of so many, they were missionary outreach. almost 40 years in the Missions – Japan, concerned that perhaps the gifts the Hispanic Community in the USA and which came from wonderful people, The Oblates, whether in Cotabato, Manila, Mexico and now, 11 in China. They did did not meet the actual needs of the Hong Kong, Beijing or Guangzhou face not want me to mention their names people. They made mention that the many challenges (and rewards) that or their story. It needs to be told and needs of the people were not always we in the first world do not experience I will seek forgiveness when I next see in response to crises, such as the as they do. -

The Franciscan Crown in 1422, an Apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary Took Place in Assisi, to a Certain 7

History of the Franciscan Crown In 1422, an apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary took place in Assisi, to a certain 7. Assumption & Coronation Franciscan novice, named James. As a child he had a custom of daily offering a crown Vision of Friar James of roses to our Blessed Mother. When he entered the Friar Minor, he became distressed that he would no longer be able to offer this type of gift. He considered leaving when our Lady appeared to him to give him comfort and showed him another daily offering he could do. Our Lady said : “In place of the flowers that soon wither and cannot always be found, you can weave for me a crown from the flowers of your prayers … Recite one Our Father and ten How to Pray the Franciscan Crown Hail Marys while recalling the Seven Joys I experienced.” Begin with the Sign of the Cross (no creed Friar James began at once to pray as directed. or opening prayers) Meanwhile, the novice master entered and 1. Announce the first Mystery, then pray saw an angel weaving a wreath of roses and one Our Father (no Glory Be). after every tenth rose, the angel, inserted a THE 2. Pray Ten Hail Mary’s while meditating golden lily. When the wreath was finished, FRANCISCAN on the Mystery. he placed it on Friar James’ head. The novice 3. Announce second Mystery and repeat master commanded the youth to tell him CROWN one and two through the seven decades. what he had been doing; and Friar James 4. -

{Download PDF} the Way of Unknowing : Expanding Spiritual

THE WAY OF UNKNOWING : EXPANDING SPIRITUAL HORIZONS THROUGH MEDITATION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Main | 144 pages | 30 Apr 2012 | CANTERBURY PRESS NORWICH | 9781848251182 | English | London, United Kingdom The Way of Unknowing : Expanding Spiritual Horizons Through Meditation PDF Book More recently, the practices of Christian Meditation through the World Community for Christian Meditation , and Centering Prayer represent contemporary expressions of the rich tradition of Christian meditation. By July , we had 76 people registered, a number that far exceeded my wildest dreams. Although mystical experiences of divine warmth, sweetness, and song may have some spiritual value, they will often remain distractions to you in the process of piercing the cloud of unknowing So keep lifting your love up to that cloud. But not everyone is going to get it. With one click, I was in the video chapel with about 14 other people from six different countries. Do you remember what happened to the greedy beasts who approached the cloud of unknowing on Mount Sinai? More importantly, these generally good thoughts can still distract you from the contemplative life: the deeper work of loving God in the darkness. When out walking somewhere, have you ever followed your feet while being curious about where they might lead? Columba arrived in the 6 th century to found a monastery and give birth to Celtic Christianity in Scotland. If this prayer practice resonates with you, then I urge you to read these words of mine again. I needed to take this deep book about meditation in the context of Christianity in small doses, reading it over a period of months, even though it is fairly short. -

C:\Users\User\Documents\Aaadocs

Vatican Archives of the Sacred Congregation "de Propaganda Fide" 1622-1846 vol. 6 CONGRESSI 1622-1836 PART 3 1831-6 [entries nos. 001-234] 407 408 Table of Contents of Part 3 413 Congressi, America Settentrionale (nos. 001-234) 409 410 ENTRIES 1831-6 (nos. 001-234) 411 412 ENTRIES ENTRY NUMBER: 001 SERIES: Congressi, America Settentrionale VOLUME: 3 (1831-6) FOLIOS: 6rv-7rv LANGUAGE: English LOCATION: Rome DATE: 03 oct 1833 AUTHOR: Thomas Weld, cardinal RECIPIENT: Macdonell, bishop [Alexander McDonell, bishop of Kingston], in Glengarry TYPE OF DOCUMENT: Autograph copy signed DESCRIPTION: The writer acknowledges the addressee's letter of 2 jul [02 jul 1833]. As it preceded W.J. O'Grady [William John O'Grady] "a few days" [f.6r], the "printed account of that Gentleman which it contained" [f.6r] has been most useful. A further letter will address the W.J. O.Grady [William John O'Grady] issue. The writer also acnowledges two other letters from the addressee. The first was dated in aug [00 aug 1832], and was received towards the end of last year [1832]. The second letter was dated "on the outside" [f.6r] 28 nov 1832, was directed via Le Havre, arrived on 7 mar [07 mar 1833], and it contained the postulation for R. Gaulin [Rémi Gaulin]. The copy sent via England was never received, the last one received from there being dated 9 sep [09 sep 1832]. Bulls forr Gaulin [Rémi Gaulin] should have been received by the addressee. Larkin [John Larkin], "tho' a most pious man" [f.6r], was not the right man for the addressee's diocese. -

A Selection from the ASCETICAL LETTERS of ANTONIO ROSMINI

A selection from THE ASCETICAL LETTERS OF ANTONIO ROSMINI Volume II 1832-1836 Translated and edited by John Morris Inst. Ch. 1995 John Morris, Our Lady’s Convent, Park Road, Loughborough LE11 2EF ISBN 0 9518938 3 1 Phototypeset by The Midlands Book Typesetting Company, Loughborough Printed by Quorn Litho, Loughborough, Leics and reset with OCR 2004 ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... iii TRANSLATOR’S FOREWORD .................................................................................. 1 1. To His Holiness Pope Gregory XVI .......................................................................... 2 2. To Don Sebastian De Apollonia at Udine ................................................................. 4 3. To the deacon Don Clemente Alvazzi at Domodossola ........................................... 6 4. To Don G. B. Loewenbruck at Domodossola ........................................................... 7 5. To Don Pietro Bruti (curate at Praso) ...................................................................... 8 6. To Don Giacomo Molinari at Domodossola ............................................................. 9 7. To the priests Lissandrini and Teruggi at Arona .................................................. 10 8. To Niccolò Tommaseo in Florence .......................................................................... 12 9. To Don G. B. Loewenbruck at Domodossola ........................................................ -

Monsignor Lorenzo Gastaldi (1815 – 1883)

Monsignor Lorenzo Gastaldi (1815 – 1883) by Domenico Mariani (Translated by J.Anthony Dewhirst) The second Rosminian Bishop, a contemporary and fellow participant with Monsignor Cardozo Ayres in the first Vatican Council, was Monsignor Lorenzo Gastaldi, firstly bishop of Saluzzo (1867–1871), then archbishop of Turin (1871–1883). He was born at Turin on 18 March 1815, a year after the return of king Victor Emmanuel I from his exile in Sardinia and a little before the conclusion of the Congress of Vienna (9 June 1815). His family were of Chierese extraction. His father Bartolomeo was a notable advocate, his mother Margherita Volpato was a housewife. It was a big family of thirteen children, (eight boys and five girls) of which Lorenzo was the eldest. Giuseppe Tuninetti, who is my guide, writes, ‘That it was a middle class, cultured, affluent family, with a markedly legal tradition’. (L.Gastaldi, Ed.Piemme, p.15). Lorenzo began his classical studies as an external scholar ‘in the College of the Carmine (or of the Nobles), run by the Jesuits. The cultural, moral and religious formation ‘was characterised by the serious and rigid method of the Jesuit colleges’ (Tunetti, ibid. p. 17). He felt his vocation to the priesthood when he was 14. At first his father was annoyed but later listened to him and on 30 September 1839 he would receive the clerical habit in his parish of the Madonna del Carmine. But he did not enter the seminary. He enrolled at University as an external student (a common occurrence at that time), and many factors favoured the best possible outcome. -

Liturgical Press Style Guide

STYLE GUIDE LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org STYLE GUIDE Seventh Edition Prepared by the Editorial and Production Staff of Liturgical Press LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design by Ann Blattner © 1980, 1983, 1990, 1997, 2001, 2004, 2008 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Printed in the United States of America. Contents Introduction 5 To the Author 5 Statement of Aims 5 1. Submitting a Manuscript 7 2. Formatting an Accepted Manuscript 8 3. Style 9 Quotations 10 Bibliography and Notes 11 Capitalization 14 Pronouns 22 Titles in English 22 Foreign-language Titles 22 Titles of Persons 24 Titles of Places and Structures 24 Citing Scripture References 25 Citing the Rule of Benedict 26 Citing Vatican Documents 27 Using Catechetical Material 27 Citing Papal, Curial, Conciliar, and Episcopal Documents 27 Citing the Summa Theologiae 28 Numbers 28 Plurals and Possessives 28 Bias-free Language 28 4. Process of Publication 30 Copyediting and Designing 30 Typesetting and Proofreading 30 Marketing and Advertising 33 3 5. Parts of the Work: Author Responsibilities 33 Front Matter 33 In the Text 35 Back Matter 36 Summary of Author Responsibilities 36 6. Notes for Translators 37 Additions to the Text 37 Rearrangement of the Text 37 Restoring Bibliographical References 37 Sample Permission Letter 38 Sample Release Form 39 4 Introduction To the Author Thank you for choosing Liturgical Press as the possible publisher of your manuscript. -

Pope Benedict XVI Praised Te Life An

23/05/2020 bededict Pope praises, Vatican beatifies Italian whose writings were condemned By Carol Glatz Catholic News Service VATICAN CITY (CNS) -- Pope Benedict XVI praised te life and example of a 19th-century Italian philosopher and religious-order founder whose writings had been condemned by the church until six years ago. Blessed Antonio Rosmini was a great priest and an "illustrious man of culture" who generously dedicated his life to harmonizing the relationship between reason and faith, the pope said just a few hours before Cardinal Jose Saraiva Martins led the Nov. 18 beatification ceremony in the northern Italian city of Novara. In remarks made shortly after his midday Angelus prayer in St. Peter's Square, the pope asked that Blessed Rosmini's example help the church, "especially Italian ecclesial communities, grow in the awareness that the light of human reason and grace, when they walk together, become a source of blessing for the human person and for society." Blessed Rosmini, who lived 1797-1855, founded the Institute of Charity -- also known as the Rosminian Fathers -- and the Congregation of the Rosminian Sisters of Providence. The road to his beatification had been impeded by an 1887 Vatican condemnation of 40 proposals selected from works written by the Italian priest. But in 2001, the Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, headed then by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger who is now Pope Benedict, declared that the positions condemned 114 years ago did not accurately reflect Blessed Rosmini's thinking or beliefs. Historians said the propositions were pulled out of the context in which they were written. -

Celebrating 90 Years of Monastic Life. 1927-2017

LENSTAL ABBEY CHRONICLE Celebrating 90 years of GLENSTAL ABBEY monastic life. Murroe, Co Limerick www.glenstal.org 1927-2017 www.glenstal.com (061)621000 S T A Y I N TOUCH WITH G L E N S T A L ABBEY If you would like to receive emails from Glenstal about events and other goings on please join our email list on our website. You can decide what type of emails you will receive and can change this at any stage. Your data will not be used for any other purpose. 1 | P a g e CELEBRATING 90 YEARS OF MONASTIC LIFE 1 9 2 7 - 2 0 1 7 Welcome Contents On the 90th anniversary of our foundation it is our pleasure to share Where in the World…… page 3 with you, friends, benefactors, Oblates at Glenstal….. page 6 parents, students, colleagues and School Choir…………… page 8 visitors, something of the variety and richness of life here in Glenstal Out of Africa…………… page 10 Abbey. In the pages of this My Year in Glenstal Chronicle we hope to bring alive and UL…………………… page 13 the place which we are privileged Glenstal Abbey Farm… page 14 to call home. Thinking of Monastic Life……………………….. page 15 We have come a very long Life as a Novice……….. page 15 way from those early days when the first Belgian monks arrived here Malartú Daltaí le back in 1927. What has been Scoileanna thar Lear…. page 18 achieved is thanks in no small Guest House……………. page 19 measure to the kindness and Retreat Days……………. -

Father Giovanni Gaddo (8Th Provost General)

Father Giovanni Gaddo (8th Provost General) by Domenico Mariani (Translated by J. Anthony Dewhirst) Is it possible that a little boy of 12 could be convinced that he had a religious vocation, to the point of devoting himself to serve the Lord all his life with the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience in a religious Institute? Would he have sufficient maturity and knowledge of his own powers and human life to be definitely sure about it? Or would it not rather be autosuggestion, domestic economic problems, or the influence of some good person influencing his choice? We know how modern psychologists would answer these questions. But we can say positively and absolutely ‘yes’. This is borne out by the reality of the facts; for instance, his life, the supernatural gift of a religious vocation, in which grace is grafted on to human nature, and incessant prayer reinforcing his human efforts. Giovanni Ferdinando Angelo Gaddo was born of Carlo and Maria Amiotti at Vercelli, the Casa Borgogna in the Via del Duomo, on 7 February1895. His father was a worker in marble, and this work provided for the upkeep of the family. His mother was a housewife and died early (1903?), so little Giovanni and his sister Lucia (a year his junior) were looked after by their grandmother. But she also passed away in 1907 and the Parish Priest of Crescentino, Don Pietro Gianotti, taking an interest in the family, wrote to Don Policarpo Garibaldi, the Novice Master at Calvario in Domodossola, in order that he might intercede with the Provincial, Giambattista Pagani, to accept the boy into the Institute of Charity. -

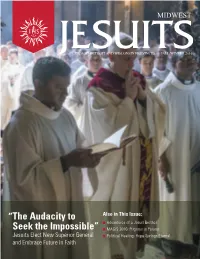

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr. -

Works of Antonio Rosmini in English and a List of Works About His Writings

A List of the Works of Antonio Rosmini in English and a List of Works about his Writings. Classified: a) According to subject matter b) According to date c) According to author Works by Antonio Rosmini Translated into English Ascetical Title Translator Publisher Constitutions of the Institute of Charity D. A. Cleary 1969 Constitutions, (suggested as suitable for all) D. A. Cleary 1969 Constitutions of the Institute of Charity D. A. Cleary Durham 1992 Apostolic Letters D. A. Cleary 1969 Rule of Life/Directory Ed. Gen. Curia Rome 1990 Common Rules Richardson 1849 Reprint 1849 Leetham Derrys Wood 1960 Gen. Curia Rome 1994 Maxims of Perfection Prior Park 1840 Richardson 1844 Reprinted 1846 Reprinted 1849 Reprinted 1855 W. A. Johnson Burns Oates 1887 Reprinted 1888 C.T.S 1908 Revised Sam. Walker 1948 D.T.L. 1962 D. A. Cleary(Ros.Spirit.) Guys. Cardiff 1978 Mary F. Ingoldsby Naas, Ireland 1985 D. A.Cleary (Ros.Revisit) Quorn 1992 Selected Letters Gazzola (??) R&T. Washbourne 1901 Counsels to Religious.Superiors Claude R. Leetham Burns Oates 1961 Two Letters to Sisters of Providence John Henry Grey ? The Ascetical Letters of Antonio Rosmini I-VI John. F. Morris Quorn 1993-8 Meditations for a Spiritual Retreat J. Hopewell 1980 In the School of the Father John. S. Burns 1950 Discourses on Religious and Moral Subjects James Duffy 1882 Spiritual Admonitions St Wms. Press 1898 Title Translator Publisher A Spiritual Nosegay (Rosmini’s thoughts) St Wms. Press 1889 Considerations on the Virtue of Humility Signini Typed Script 1975 The Doctrine of Charity J. A.