A Closer Look at Instruction Set Architectures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdp11-40.Pdf

processor handbook digital equipment corporation Copyright© 1972, by Digital Equipment Corporation DEC, PDP, UNIBUS are registered trademarks of Digital Equipment Corporation. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1·1 1.1 GENERAL ............................................. 1·1 1.2 GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS . 1·2 1.2.1 The UNIBUS ..... 1·2 1.2.2 Central Processor 1·3 1.2.3 Memories ........... 1·5 1.2.4 Floating Point ... 1·5 1.2.5 Memory Management .............................. .. 1·5 1.3 PERIPHERALS/OPTIONS ......................................... 1·5 1.3.1 1/0 Devices .......... .................................. 1·6 1.3.2 Storage Devices ...................................... .. 1·6 1.3.3 Bus Options .............................................. 1·6 1.4 SOFTWARE ..... .... ........................................... ............. 1·6 1.4.1 Paper Tape Software .......................................... 1·7 1.4.2 Disk Operating System Software ........................ 1·7 1.4.3 Higher Level Languages ................................... .. 1·7 1.5 NUMBER SYSTEMS ..................................... 1-7 CHAPTER 2 SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE. 2-1 2.1 SYSTEM DEFINITION .............. 2·1 2.2 UNIBUS ......................................... 2-1 2.2.1 Bidirectional Lines ...... 2-1 2.2.2 Master-Slave Relation .. 2-2 2.2.3 Interlocked Communication 2-2 2.3 CENTRAL PROCESSOR .......... 2-2 2.3.1 General Registers ... 2-3 2.3.2 Processor Status Word ....... 2-4 2.3.3 Stack Limit Register 2-5 2.4 EXTENDED INSTRUCTION SET & FLOATING POINT .. 2-5 2.5 CORE MEMORY . .... 2-6 2.6 AUTOMATIC PRIORITY INTERRUPTS .... 2-7 2.6.1 Using the Interrupts . 2-9 2.6.2 Interrupt Procedure 2-9 2.6.3 Interrupt Servicing ............ .. 2-10 2.7 PROCESSOR TRAPS ............ 2-10 2.7.1 Power Failure .............. -

Towards Attack-Tolerant Trusted Execution Environments

Master’s Programme in Security and Cloud Computing Towards attack-tolerant trusted execution environments Secure remote attestation in the presence of side channels Max Crone MASTER’S THESIS Aalto University — KTH Royal Institute of Technology MASTER’S THESIS 2021 Towards attack-tolerant trusted execution environments Secure remote attestation in the presence of side channels Max Crone Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Technology. Espoo, 12 July 2021 Supervisors: Prof. N. Asokan Prof. Panagiotis Papadimitratos Advisors: Dr. HansLiljestrand Dr. Lachlan Gunn Aalto University School of Science KTH Royal Institute of Technology School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Master’s Programme in Security and Cloud Computing Abstract Aalto University, P.O. Box 11000, FI-00076 Aalto www.aalto.fi Author Max Crone Title Towards attack-tolerant trusted execution environments: Secure remote attestation in the presence of side channels School School of Science Master’s programme Security and Cloud Computing Major Security and Cloud Computing Code SCI3113 Supervisors Prof. N. Asokan, Prof. Panagiotis Papadimitratos Advisors Dr. Hans Liljestrand, Dr. Lachlan Gunn Level Master’s thesis Date 12 July 2021 Pages 64 Language English Abstract In recent years, trusted execution environments (TEEs) have seen increasing deployment in comput- ing devices to protect security-critical software from run-time attacks and provide isolation from an untrustworthy operating system (OS). A trusted party verifies the software that runs in a TEE using remote attestation procedures. However, the publication of transient execution attacks such as Spectre and Meltdown revealed fundamental weaknesses in many TEE architectures, including Intel Software Guard Exentsions (SGX) and Arm TrustZone. -

Instruction Pipelining (1 of 7)

Chapter 5 A Closer Look at Instruction Set Architectures Objectives • Understand the factors involved in instruction set architecture design. • Gain familiarity with memory addressing modes. • Understand the concepts of instruction- level pipelining and its affect upon execution performance. 5.1 Introduction • This chapter builds upon the ideas in Chapter 4. • We present a detailed look at different instruction formats, operand types, and memory access methods. • We will see the interrelation between machine organization and instruction formats. • This leads to a deeper understanding of computer architecture in general. 5.2 Instruction Formats (1 of 31) • Instruction sets are differentiated by the following: – Number of bits per instruction. – Stack-based or register-based. – Number of explicit operands per instruction. – Operand location. – Types of operations. – Type and size of operands. 5.2 Instruction Formats (2 of 31) • Instruction set architectures are measured according to: – Main memory space occupied by a program. – Instruction complexity. – Instruction length (in bits). – Total number of instructions in the instruction set. 5.2 Instruction Formats (3 of 31) • In designing an instruction set, consideration is given to: – Instruction length. • Whether short, long, or variable. – Number of operands. – Number of addressable registers. – Memory organization. • Whether byte- or word addressable. – Addressing modes. • Choose any or all: direct, indirect or indexed. 5.2 Instruction Formats (4 of 31) • Byte ordering, or endianness, is another major architectural consideration. • If we have a two-byte integer, the integer may be stored so that the least significant byte is followed by the most significant byte or vice versa. – In little endian machines, the least significant byte is followed by the most significant byte. -

Binary and Hexadecimal

Binary and Hexadecimal Binary and Hexadecimal Introduction This document introduces the binary (base two) and hexadecimal (base sixteen) number systems as a foundation for systems programming tasks and debugging. In this document, if the base of a number might be ambiguous, we use a base subscript to indicate the base of the value. For example: 45310 is a base ten (decimal) value 11012 is a base two (binary) value 821716 is a base sixteen (hexadecimal) value Why do we need binary? The binary number system (also called the base two number system) is the native language of digital computers. No matter how elegantly or naturally we might interact with today’s computers, phones, and other smart devices, all instructions and data are ultimately stored and manipulated in the computer as binary digits (also called bits, where a bit is either a 0 or a 1). CPUs (central processing units) and storage devices can only deal with information in this form. In a computer system, absolutely everything is represented as binary values, whether it’s a program you’re running, an image you’re viewing, a video you’re watching, or a document you’re writing. Everything, including text and images, is represented in binary. In the “old days,” before computer programming languages were available, programmers had to use sequences of binary digits to communicate directly with the computer. Today’s high level languages attempt to shield us from having to deal with binary at all. However, there are a few reasons why it’s important for programmers to understand the binary number system: 1. -

Programming Model, Address Mode, HC12 Hardware Introduction

EEL 4744C: Microprocessor Applications Lecture 2 Programming Model, Address Mode, HC12 Hardware Introduction Dr. Tao Li 1 Reading Assignment • Microcontrollers and Microcomputers: Chapter 3, Chapter 4 • Software and Hardware Engineering: Chapter 2 Or • Software and Hardware Engineering: Chapter 4 Plus • CPU12 Reference Manual: Chapter 3 • M68HC12B Family Data Sheet: Chapter 1, 2, 3, 4 Dr. Tao Li 2 EEL 4744C: Microprocessor Applications Lecture 2 Part 1 CPU Registers and Control Codes Dr. Tao Li 3 CPU Registers • Accumulators – Registers that accumulate answers, e.g. the A Register – Can work simultaneously as the source register for one operand and the destination register for ALU operations • General-purpose registers – Registers that hold data, work as source and destination register for data transfers and source for ALU operations • Doubled registers – An N-bit CPU in general uses N-bit data registers – Sometimes 2 of the N-bit registers are used together to double the number of bits, thus “doubled” registers Dr. Tao Li 4 CPU Registers (2) • Pointer registers – Registers that address memory by pointing to specific memory locations that hold the needed data – Contain memory addresses (without offset) • Stack pointer registers – Pointer registers dedicated to variable data and return address storage in subroutine calls • Index registers – Also used to address memory – An effective memory address is found by adding an offset to the content of the involved index register Dr. Tao Li 5 CPU Registers (3) • Segment registers – In some architectures, memory addressing requires that the physical address be specified in 2 parts • Segment part: specifies a memory page • Offset part: specifies a particular place in the page • Condition code registers – Also called flag or status registers – Hold condition code bits generated when instructions are executed, e.g. -

Appendix D an Alternative to RISC: the Intel 80X86

D.1 Introduction D-2 D.2 80x86 Registers and Data Addressing Modes D-3 D.3 80x86 Integer Operations D-6 D.4 80x86 Floating-Point Operations D-10 D.5 80x86 Instruction Encoding D-12 D.6 Putting It All Together: Measurements of Instruction Set Usage D-14 D.7 Concluding Remarks D-20 D.8 Historical Perspective and References D-21 D An Alternative to RISC: The Intel 80x86 The x86 isn’t all that complex—it just doesn’t make a lot of sense. Mike Johnson Leader of 80x86 Design at AMD, Microprocessor Report (1994) © 2003 Elsevier Science (USA). All rights reserved. D-2 I Appendix D An Alternative to RISC: The Intel 80x86 D.1 Introduction MIPS was the vision of a single architect. The pieces of this architecture fit nicely together and the whole architecture can be described succinctly. Such is not the case of the 80x86: It is the product of several independent groups who evolved the architecture over 20 years, adding new features to the original instruction set as you might add clothing to a packed bag. Here are important 80x86 milestones: I 1978—The Intel 8086 architecture was announced as an assembly language– compatible extension of the then-successful Intel 8080, an 8-bit microproces- sor. The 8086 is a 16-bit architecture, with all internal registers 16 bits wide. Whereas the 8080 was a straightforward accumulator machine, the 8086 extended the architecture with additional registers. Because nearly every reg- ister has a dedicated use, the 8086 falls somewhere between an accumulator machine and a general-purpose register machine, and can fairly be called an extended accumulator machine. -

The Birth, Evolution and Future of Microprocessor

The Birth, Evolution and Future of Microprocessor Swetha Kogatam Computer Science Department San Jose State University San Jose, CA 95192 408-924-1000 [email protected] ABSTRACT timed sequence through the bus system to output devices such as The world's first microprocessor, the 4004, was co-developed by CRT Screens, networks, or printers. In some cases, the terms Busicom, a Japanese manufacturer of calculators, and Intel, a U.S. 'CPU' and 'microprocessor' are used interchangeably to denote the manufacturer of semiconductors. The basic architecture of 4004 same device. was developed in August 1969; a concrete plan for the 4004 The different ways in which microprocessors are categorized are: system was finalized in December 1969; and the first microprocessor was successfully developed in March 1971. a) CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computers) Microprocessors, which became the "technology to open up a new b) RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computers) era," brought two outstanding impacts, "power of intelligence" and "power of computing". First, microprocessors opened up a new a) VLIW(Very Long Instruction Word Computers) "era of programming" through replacing with software, the b) Super scalar processors hardwired logic based on IC's of the former "era of logic". At the same time, microprocessors allowed young engineers access to "power of computing" for the creative development of personal 2. BIRTH OF THE MICROPROCESSOR computers and computer games, which in turn led to growth in the In 1970, Intel introduced the first dynamic RAM, which increased software industry, and paved the way to the development of high- IC memory by a factor of four. -

Computer Organization & Architecture Eie

COMPUTER ORGANIZATION & ARCHITECTURE EIE 411 Course Lecturer: Engr Banji Adedayo. Reg COREN. The characteristics of different computers vary considerably from category to category. Computers for data processing activities have different features than those with scientific features. Even computers configured within the same application area have variations in design. Computer architecture is the science of integrating those components to achieve a level of functionality and performance. It is logical organization or designs of the hardware that make up the computer system. The internal organization of a digital system is defined by the sequence of micro operations it performs on the data stored in its registers. The internal structure of a MICRO-PROCESSOR is called its architecture and includes the number lay out and functionality of registers, memory cell, decoders, controllers and clocks. HISTORY OF COMPUTER HARDWARE The first use of the word ‘Computer’ was recorded in 1613, referring to a person who carried out calculation or computation. A brief History: Computer as we all know 2day had its beginning with 19th century English Mathematics Professor named Chales Babage. He designed the analytical engine and it was this design that the basic frame work of the computer of today are based on. 1st Generation 1937-1946 The first electronic digital computer was built by Dr John V. Atanasoff & Berry Cliford (ABC). In 1943 an electronic computer named colossus was built for military. 1946 – The first general purpose digital computer- the Electronic Numerical Integrator and computer (ENIAC) was built. This computer weighed 30 tons and had 18,000 vacuum tubes which were used for processing. -

Low-Power Microprocessor Based on Stack Architecture

Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao Low-power Microprocessor based on Stack Architecture Stack on based Microprocessor Low-power Master’s Thesis Low-power Microprocessor based on Stack Architecture Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao Series of Master’s theses Department of Electrical and Information Technology LU/LTH-EIT 2015-464 Department of Electrical and Information Technology, http://www.eit.lth.se Faculty of Engineering, LTH, Lund University, September 2015. Department of Electrical and Information Technology Master of Science Thesis Low-power Microprocessor based on Stack Architecture Supervisors: Author: Prof. Joachim Rodrigues Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao Prof. Anders Ard¨o Lund 2015 © The Department of Electrical and Information Technology Lund University Box 118, S-221 00 LUND SWEDEN This thesis is set in Computer Modern 10pt, with the LATEX Documentation System ©Girish Aramanekoppa Subbarao 2015 Printed in E-huset Lund, Sweden. Sep. 2015 Abstract There are many applications of microprocessors in embedded applications, where power efficiency becomes a critical requirement, e.g. wearable or mobile devices in healthcare, space instrumentation and handheld devices. One of the methods of achieving low power operation is by simplifying the device architecture. RISC/CISC processors consume considerable power because of their complexity, which is due to their multiplexer system connecting the register file to the func- tional units and their instruction pipeline system. On the other hand, the Stack machines are comparatively less complex due to their implied addressing to the top two registers of the stack and smaller operation codes. This makes the instruction and the address decoder circuit simple by eliminating the multiplex switches for read and write ports of the register file. -

IBM Z/Architecture Reference Summary

z/Architecture IBMr Reference Summary SA22-7871-06 . z/Architecture IBMr Reference Summary SA22-7871-06 Seventh Edition (August, 2010) This revision differs from the previous edition by containing instructions related to the facilities marked by a bar under “Facility” in “Preface” and minor corrections and clari- fications. Changes are indicated by a bar in the margin. References in this publication to IBM® products, programs, or services do not imply that IBM intends to make these available in all countries in which IBM operates. Any reference to an IBM program product in this publication is not intended to state or imply that only IBM’s program product may be used. Any functionally equivalent pro- gram may be used instead. Additional copies of this and other IBM publications may be ordered or downloaded from the IBM publications web site at http://www.ibm.com/support/documentation. Please direct any comments on the contents of this publication to: IBM Corporation Department E57 2455 South Road Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-5400 USA IBM may use or distribute whatever information you supply in any way it believes appropriate without incurring any obligation to you. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2001-2010. All rights reserved. US Government Users Restricted Rights — Use, duplication, or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. ii z/Architecture Reference Summary Preface This publication is intended primarily for use by z/Architecture™ assembler-language application programmers. It contains basic machine information summarized from the IBM z/Architecture Principles of Operation, SA22-7832, about the zSeries™ proces- sors. It also contains frequently used information from IBM ESA/390 Common I/O- Device Commands and Self Description, SA22-7204, IBM System/370 Extended Architecture Interpretive Execution, SA22-7095, and IBM High Level Assembler for MVS & VM & VSE Language Reference, SC26-4940. -

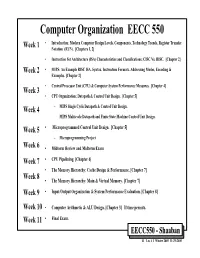

Computer Organization EECC 550 • Introduction: Modern Computer Design Levels, Components, Technology Trends, Register Transfer Week 1 Notation (RTN)

Computer Organization EECC 550 • Introduction: Modern Computer Design Levels, Components, Technology Trends, Register Transfer Week 1 Notation (RTN). [Chapters 1, 2] • Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) Characteristics and Classifications: CISC Vs. RISC. [Chapter 2] Week 2 • MIPS: An Example RISC ISA. Syntax, Instruction Formats, Addressing Modes, Encoding & Examples. [Chapter 2] • Central Processor Unit (CPU) & Computer System Performance Measures. [Chapter 4] Week 3 • CPU Organization: Datapath & Control Unit Design. [Chapter 5] Week 4 – MIPS Single Cycle Datapath & Control Unit Design. – MIPS Multicycle Datapath and Finite State Machine Control Unit Design. Week 5 • Microprogrammed Control Unit Design. [Chapter 5] – Microprogramming Project Week 6 • Midterm Review and Midterm Exam Week 7 • CPU Pipelining. [Chapter 6] • The Memory Hierarchy: Cache Design & Performance. [Chapter 7] Week 8 • The Memory Hierarchy: Main & Virtual Memory. [Chapter 7] Week 9 • Input/Output Organization & System Performance Evaluation. [Chapter 8] Week 10 • Computer Arithmetic & ALU Design. [Chapter 3] If time permits. Week 11 • Final Exam. EECC550 - Shaaban #1 Lec # 1 Winter 2005 11-29-2005 Computing System History/Trends + Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) Fundamentals • Computing Element Choices: – Computing Element Programmability – Spatial vs. Temporal Computing – Main Processor Types/Applications • General Purpose Processor Generations • The Von Neumann Computer Model • CPU Organization (Design) • Recent Trends in Computer Design/performance • Hierarchy -

Advanced Architecture Intel Microprocessor History

Advanced Architecture Intel microprocessor history Computer Organization and Assembly Languages Yung-Yu Chuang with slides by S. Dandamudi, Peng-Sheng Chen, Kip Irvine, Robert Sedgwick and Kevin Wayne Early Intel microprocessors The IBM-AT • Intel 8080 (1972) • Intel 80286 (1982) – 64K addressable RAM – 16 MB addressable RAM – 8-bit registers – Protected memory – CP/M operating system – several times faster than 8086 – 5,6,8,10 MHz – introduced IDE bus architecture – 29K transistors – 80287 floating point unit • Intel 8086/8088 (1978) my first computer (1986) – Up to 20MHz – IBM-PC used 8088 – 134K transistors – 1 MB addressable RAM –16-bit registers – 16-bit data bus (8-bit for 8088) – separate floating-point unit (8087) – used in low-cost microcontrollers now 3 4 Intel IA-32 Family Intel P6 Family • Intel386 (1985) • Pentium Pro (1995) – 4 GB addressable RAM – advanced optimization techniques in microcode –32-bit registers – More pipeline stages – On-board L2 cache – paging (virtual memory) • Pentium II (1997) – Up to 33MHz – MMX (multimedia) instruction set • Intel486 (1989) – Up to 450MHz – instruction pipelining • Pentium III (1999) – Integrated FPU – SIMD (streaming extensions) instructions (SSE) – 8K cache – Up to 1+GHz • Pentium (1993) • Pentium 4 (2000) – Superscalar (two parallel pipelines) – NetBurst micro-architecture, tuned for multimedia – 3.8+GHz • Pentium D (2005, Dual core) 5 6 IA32 Processors ARM history • Totally Dominate Computer Market • 1983 developed by Acorn computers • Evolutionary Design – To replace 6502 in