Privatization and 'Agentification'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contact N°177-178 About This Issue of Contact for Health

1 Contact n°177-178 About this issue of Contact for Health: Our lead topic is AIDS and malaria and we have From Uganda, Dr Pepper, a Southern Baptist Conven- received news from East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, and tion Missionary, physician and head of the HIV clinic, and Uganda; from Southern Africa and West Africa. internal medicine at the government teaching hospital MUTH, reports his practice of Biblical holistic care and The Ecumenical HIV/AIDS Initiative in Africa was his use of latest technologies: syringes where the launched in Nairobi. p.14 & 41 needle retracts after use. p.15 The Ecumenical Advocacy Alliance will be active in the The Safe Health Care and HIV coalition is petitioning 2004 IAS AIDS Conference in Bangkok. p.4 the 2004 World Health Assembly and proposing an amendment to insure total safety. p.42 “Africa could be depopulated by AIDS to an extent Coming together to confront AIDS, is the message of the not seen since Slavery!”, Reverend Dr. Samuel Kobia, The Inter Religious Council of Uganda received from General Secretary of the WCC, told Contact : “AIDS is Rev. Sam Lawrence Ruteikara, AIDS Director. p.15 the enemy”. p.5 The Church of the Province of West Africa, Anglican Special report TANZANIA (p.7-13) Provincial Health Service in Accra, Ghana, report that “In faith, we are breaking ground slowly”. p.16 “FAIR TRADE”, Tanzania’s Deputy Health Minister Hussein A. Mwinyi tells the world, “would best assist From the South African Catholic Bishops’ Conference Africa in meeting the challenge of HIV AIDS”. p.12 AIDS Office comes a call and a commitment for treat- ment. -

Community Concerns of Orphans and Development Association (Cocoda) P

COMMUNITY CONCERNS OF ORPHANS AND DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION (COCODA) P. O. BOX 712, NJOMBE - CHAUNGINGI STREET ALONG SONGEA ROAD, OPPOSITE TANESCO REGIONAL OFFICE Email: [email protected] Website: www.cocoda.or.tz COCODA 2019 ANNUAL REPORT COMMUNITY CONCERN OF ORPHANS AND DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION REPORTING PERIOD: 1 JANUARY – 31 DECEMBER 2019 Projects Implemented Councils • SAUTI Project Njombe Region councils: Njombe Town Council • USAID KIZAZI KIPYA Project • • Njombe District Council • USAID Tulonge Afya • Makambako Town Council • Makete District Council • Wanging’ombe District Council • Ludewa District Council Prime Recipients Implementing Partners • DELOITTE CONSULTANCY LTD • LGAs JHPIEGO • • Health facilities • PACT TANZANIA • FHI360 Programme/Project Budget/Year Programme Duration • SAUTI 182,970,583 5 Years • USAID KIZAZI KIPYA 297,158,227 5 Years • USAID TULONGE AFYA 159,376,560 5 Years TOTAL: 639,505,370 Report Submitted By o Name: Mary Kahemele o Title: Executive Director o Organization: COCODA o Email address: [email protected] o Phone No: 0754 071 288 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms / Abbreviations ................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 4 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION ..................................................................................... 5 I. SAUTI PROJECT ................................................................................................. -

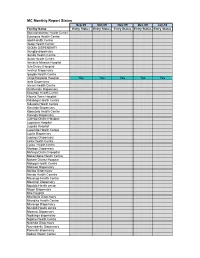

MC Monthly Report Status

MC Monthly Report Status Sep-09 Oct-09 Nov-09 Dec-09 Jan-10 Facility Name Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Bomalang'ombe Health Centre Bulongwa Health Centre Idodi Health Centre Ifwagi Health Center IGOMA DISPENSARY Ihungilo dispensary Ikonda Health Centre Ikuwo Health Centre Ilembula Mission Hospital Ilula District Hospital Imalinyi Dispensary Ipogolo Health Centre Iringa Regional Hospital Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Isele Dispensary Ismani Health Centre Itulahumba Dispensary Kasanga Health Centre Kibena Town Hospital Kidabaga Health Centre Kidugala Health Centre Kimande Dispensary Kiponzelo Health Centre Kisanga Dispensary Ludewa District Hospital Lugalawa Hospital Lugoda Hospital Lupembe Health Centre Lupila Dispensary Lupingu Dispensary Lwila Health Centre Lyasa Health centre Madege Dispensary Mafinga District Hospital Makambako Health Centre Makete District Hospital Makoga Health Centre Makowo Dispensary Maliwa Dispensary Manda Health Ceantre Mavanga Health Centre Mawengi Dispensary Mgololo Health center Migori Dispensary Milo Hospital Mtambula Dispensary Mtandika Health Centre Mtwango Dispensary Mundidi Health centre Mwatasi Dispensary Ngalanga dispensary Ngome Health Centre Nyombo Dispensary Nyumbanitu Dispensary Pomerini dispensary Sadani Health Center Saint Lukes Dispensary Tanangozi Dispensary TANWAT Hospital Tosamaganga District Hospital Ugwachanya Dispensary Ujuni Dispensary Ukalawa dispensary Uliwa Dispensary Usokami HC Key: Not Applicable Available Not Available Feb-10 Mar-10 Apr-10 May-10 Jun-10 Jul-10 -

United Republic of Tanzania

United Republic of Tanzania The United Republic of Tanzania Jointly prepared by Ministry of Finance and Planning, National Bureau of Statistics and Njombe Regional Secretariat Njombe Region National Bureau of Statistics Njombe Dodoma November, 2020 Njombe Region Socio-Economic Profile, 2018 Foreword The goals of Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025 are in line with United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and are pursued through the National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP) or MKUKUTA II. The major goals are to achieve a high-quality livelihood for the people, attain good governance through the rule of law and develop a strong and competitive economy. To monitor the progress in achieving these goals, there is need for timely, accurate data and information at all levels. Problems especially in rural areas are many and demanding. Social and economic services require sustainable improvement. The high primary school enrolment rates recently attained have to be maintained and so is the policy of making sure that all pupils who passed Primary School Leaving Examination must join form one. The Nutrition situation is still precarious; infant and maternal mortality rates continue to be high and unemployment triggers mass migration of youths from rural areas to the already overcrowded urban centres. Added to the above problems, is the menace posed by HIV/AIDS, the prevalence of which hinders efforts to advance into the 21st century of science and technology. The pandemic has been quite severe among the economically active population leaving in its wake an increasing number of orphans, broken families and much suffering. AIDS together with environmental deterioration are problems which cannot be ignored. -

An End of Project Review for the Agro-Dealer Development Project Funded by Agra in Tanzania

AN END OF PROJECT REVIEW FOR THE AGRO-DEALER DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FUNDED BY AGRA IN TANZANIA FINAL REPORT Prepared by: Kobe Konsult Ltd JUED Business Centre, 34 Garden Road, Mikocheni A, P.O. Box 32187, Dar es Salaam Phone: +255 22 277 4436 / 0754 300 767 Fax: +255 22 277 4426 Email: [email protected] August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... vii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ viii 1.0 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background and Rationale ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Evaluation Objectives and Scope ............................................................................. 1 1.2.1 Specific objectives ........................................................................................................ 2 2.0 METHODOLOGY AND APPROACH ............................................................................. 2 2.1 Review of Secondary Data ....................................................................................... -

Potentials of Agrarian Cluster Development for Improving Smallholder’S Income – a Case Study from the SAGCOT Initiative in Tanzania

_______________________________________________________________ Universität zu Köln Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche-Fakultät Geographisches Institut Bachelorarbeit zur Erlangung des Grades „Bachelor of Science“ Potentials of Agrarian Cluster Development for Improving Smallholder’s Income – a case study from the SAGCOT initiative in Tanzania Veronika Charlotte Steffens Matrikelnummer: 5639913 [email protected] Richard-Wagner-Str. 22 Eingereicht am 21.11.2016 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Peter Dannenberg 50181 Bedburg Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Javier Revilla Diez Tel.: 0174 957 11 24 – 0 – . Table of Contents . LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................... II LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... III 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 2 CONCEPTIONAL BACKGROUND: POTENTIALS OF CLUSTER-BASED DEVELOPMENT IN AGRICULTURE ............................................................................. 2 2.1 THE IDEA OF CLUSTER AND CLUSTER INITIATIVE – GENERAL DEFINITIONS ........................................ 2 2.2 CLUSTER-RELATED CONCEPTS FOR AGRICULTURAL AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT ............................... 4 2.3 TAKING THE CONCEPT TO THE GLOBAL SOUTH: CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS IN AFRICA ... 6 2.4 FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................................ -

United Republic of Tanzania

United Republic of Tanzania POWER SYSTEM MASTER PLAN 2012 UPDATE Produced by: Ministry of Energy and Minerals May 2013 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AfDB African Development Bank BoT Bank of Tanzania CCM Chama Cha Mapinduzi COSS Cost of Service Study DSM Demand-side Management EAPMP East Africa Power Master Plan EEPCo Ethiopia Electric Power Company EPC Engineering, Procurement and Construction Contract ERT Energizing Rural Transformation ESKOM Electricity Supply Company (RSA) EWURA Energy and Water Utilities Regulatory Authority FYDP Five Years Development Plan GoT Government of the United Republic of Tanzania GWh Gigawatt-hours = 1,000,000,000 watt-hours GWh Gigawatt-hours = 1,000,000,000 watt-hours IDC Interest During Construction IPP Independent Power Producer IPTL Independent Power Tanzania Limited KPLC Kenya Power and Lighting Company kWh Kilowatt-hours = 1,000 watt-hours LTPP Long Term Plan Perspective MCA-T Millennium Challenge Account Tanzania MEM Ministry of Energy and Minerals MKUKUTA Mkakati wa Kukuza Uchumi na Kupunguza Umasikini Tanzania MKUZA Mkakati wa Kukuza Uchumi Zanzibar MoF Ministry of Finance MPEE Ministry of Planning, Economy and Empowerment MPIP Medium-Term Public Investment Plan MVA Mega Volt Ampere MVAr Mega Volt Ampere Reactive MW Megawatt = 1000,000 watts MWh Megawatt-hours = 1,000,000 watt-hours NBS National Bureau of Statistics NDC National Development Corporation NGO Non-Governmental Organisations POPC President‘s Office Planning Commission PPA Power Purchase Agreement i PPP Public Private Partnership PSMP Power System Master Plan R&D Research and Development REA Rural Energy Agency REB Rural Energy Board REF Rural Energy Fund SADC Southern African Development Community SAPP South African Power Pool SEZ Special Economic Zone SME Small and Medium Enterprises SNC SNC-Lavalin International Inc. -

A Report on Avocado Value Chain Mapping in Siha And

A REPORT ON AVOCADO VALUE CHAIN MAPPING IN SIHA AND NJOMBE DISTRICTS May 20th, 2014 Prepared by Hebron A. Mwakalinga P.O. Box 78496, Dar es Salaam Phone : +255 786 171 000 E-mail: [email protected] Report on Avocado Value Chain Mapping in Siha and Njombe ACKNOWLGEMENT AND DISCLAIMER The Consultant thanks UNDP and MIT for awarding this interesting and important assignment of mapping avocado value chain in Siha and Njombe. It is important because of the potential the crop has in improving rural household incomes, foreign exchange earnings, nutrition to Tanzanians as well as environment protection. The Consultant team acknowledges the support received from UNDP and MIT staff namely Mr. Ernest Salla – Practice Specialist Trade/Private Sector Development, Mr Yona Shamo – Procurement Associate and Ms Irene Kajuna – Procurement Analyst. At the Ministry of Industry and Trade the work was supervised by SME Department Staff particularly Dr. Fidea Mgina – Assistant Director and Mr. Deogratius Sangu – Trade Officer who also accompanied the team in the field. In Kilimanjaro we acknowledge RAS staff namely Mr. Simon Msoka and Frederick Mushi for their assistance in gathering production data from District Councils and Mr. Frederick Mushi for participating at the Siha’s stakeholders’ workshop. At Siha the Acting District Executive Director Mr. Jonas P. Moses is thanked by the Team for gracing the workshop. Special appreciations go to Mr. A. Siayo Agriculture Officer who coordinated all field activities in Siha. In Njombe special thanks are extended to Njombe Regional Commissioner Captain A. G. Msangi who dedicated about two hours of his precious time for consultation with the study team, alongside the Regional Commissioner were the Assistant RAS – Productive Sector Mr. -

Makambako Town Council Strategic Plan 2016/17-2020/21

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRESIDENT’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT MAKAMBAKO TOWN COUNCIL STRATEGIC PLAN 2016/17-2020/21 Prepared by: Town Director’s Office Makambako Town Council P O BOX 405, Makambako, Tanzania Tel: 026- 2773004 Fax 026- 27730445 Email: [email protected] August, 2016 i Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................... iv Definition of terms ........................................................................................................................................... vi Message from his Honorary the Chairman ................................................................................................ viii Forward by Town Director ............................................................................................................................ ix Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ xi CHAPTER ONE -INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Socio-Economic Development ................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Methodology ......................................................................................................................... -

VIPAJI NJOMBE MKOA.Xlsx

MKOA WA NJOMBE ORODHA YA WANAFUNZI WALIOCHAGULIWA KUJIUNGA NA SHULE ZA SEKONDARI KIDATO CHA KWANZA JANUARI 2020 A: SHULE ZA BWENI 1.UFAULU MZURI (SPECIAL SCHOOLS) I: WAVULANA PReM NAMBA YA SHULE SHULE HALMASHAURI NA JINA LA MTAHINIWA NUMBER MTAHINIWA ATOKAYO AENDAYO ATOKAYO 1 20171374982 PS2603032-039 JONATHAN VALENTINO NDEDELA SIGRID KIBAHA MJI MAKAMBAKO 2 20171375004 PS2603033-038 YOHANA JANKE SANGA UHURU KIBAHA MJI MAKAMBAKO 3 20130910264 PS2604077-001 ADAMU GERALD MAGAGA MT BAKITA KIBAHA MJI NJOMBE 4 20130910505 PS2604079-002 BRAITON KANUTH MSEMWA ST DONBOSCO KIBAHA MJI NJOMBE 5 20130966305 PS2601104-009 JOSEPH JERMANUS MGANWA MAMALILO KIBAHA LUDEWA 6 20130966300 PS2601104-004 CLINTON MUSSA MHINA MAMALILO KIBAHA LUDEWA 7 20130316694 PS2606019-004 ANTELMO INONCENT CHAMANGE IGWACHANYA KIBAHA WANGING'OMBE 8 20130763996 PS2602066-008 ETHNOS METHOD MLOWE MFUMBI KIBAHA MAKETE 9 20130327956 PS2606012-013 DIKSON JOSEPH MDUGO IGELEHEDZA KIBAHA WANGING'OMBE 10 20130260830 PS2605058-016 NICK KELVIN MTANGA ITUNDUMA KIBAHA NJOMBE VIJIJINI 2. SHULE ZA SEKONDARI UFUNDI PReM NAMBA YA SHULE SHULE HALMASHAURI NA JINA LA MTAHINIWA NUMBER MTAHINIWA ATOKAYO AENDAYO ATOKAYO 1 20171039562 PS2603033-037 TONINO IGNASI KIBIKI UHURU IFUNDA TECH MJI MAKAMBAKO 2 20130910267 PS2604077-003 ALFA DAWI YAEDA MT BAKITA IFUNDA TECH MJI NJOMBE 3 20130910272 PS2604077-006 BRIGHT CHARLES MFUNTA MT BAKITA IFUNDA TECH MJI NJOMBE 4 20171374986 PS2603032-044 KELLY VALENCE MKULA SIGRID IYUNGA TECH MJI MAKAMBAKO 5 20130909200 PS2604077-005 BONAVENTURE YERONIMUS KISWAGA MT BAKITA -

Project Proposal for Ludali Farmers Association

THE OPEN UNIVERSITY O F TANZANI A & THE SOUTHERN NEW HAMPSHIRE UNIVERSIT Y MASTER O F SCIENCE IN COMMUNITY ECONOMIC DEVELOPMEN T (2005) PROJECT PROPOSA L FO R LUDALI FARMER S ASSOCIATIO N (LUFAA) ESTER MARIA MGINA-VAN VUGT ii Supervisor Certificatio n I, Mr Felician Mutasa, supervisor o f Ester Maria Mgina- van Vugt, hereby confirm that I have read th e Projec t an d have found it acceptable for review, Signature iii Statement o f copyright No part of this Project may be reproduced, store d in any retrieval system, or transmitte d in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the author or the Open University of Tanzania/ Southern New Hampshire University in that behalf. iv Declaration by the candidate I, Ester Maria Mgina- van Vugt, hereby declare that this project paper is my own original work and that I have not submitted this paper in another University for a similar degree. Signature V Abstract The title of this project i s "A Project Proposal "for the Ludali Farmers Association (LUFAA) in Njombe. The organization has been registered a s a NGO i n 2003. In th e context of this project, th e organization requested the autho r o f this project repor t to write a project proposal. As the organization had very few activities and not any programme, i t was agreed t o develop a Strategic Plan for the organization, followed by the preparation of a Logical Framework that will be used in the writing of a project proposal, for a project o r programme prioritized by the organization in the process . -

Evaluation of the Bringing Nutrition to Scale Project in Iringa, Mbeya and Njombe

Evaluation of the Bringing Nutrition to Scale Project in Iringa, Mbeya and Njombe Regions (2013–2017) Evaluation Report 23 April 2018 Prepared by Stephen Turner (Team Leader) Bjorn Ljungqvist Joyce Kinabo Jim Grabham Proposal contacts: Evaluation of Bringing Nutrition to Scale in Iringa, Mbeya and Njombe ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DISCLAIMER The evaluation team are grateful to the nutrition colleagues at the UNICEF Country Office in Dar es Salaam and the Sub-office in Mbeya for all their support in providing information and facilitating meetings throughout this assignment. Quality support for the evaluation has been provided by the QS team assigned to the evaluation: Stephen Anderson (Food Economy Group) and Stephen Lister (Mokoro Ltd). The authors take full responsibility for the contents of this report. The designations employed, maps and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNICEF concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delineation of its frontiers or boundaries. ii Evaluation of Bringing Nutrition to Scale in Iringa, Mbeya and Njombe Contents Summary v 1. Introduction __________________________________________________ 1 1.1. Evaluation purpose and scope ___________________________________ 1 1.2. Country context ______________________________________________ 1 1.3. Nutrition in Tanzania and the project area __________________________ 2 2. The BNTS and ASRP projects _____________________________________ 5 2.1. Project description ____________________________________________ 5 2.2. Key stakeholders and linkages ___________________________________ 8 2.3. Summary of reported performance ______________________________ 10 3. Approach and methods _________________________________________ 11 3.1. Evaluation approach __________________________________________ 11 3.2.