Nber Working Paper Series Sterling in Crisis: 1964-1967

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consideration of Questions Under the Council's Responsibility for The

Chapter VIII CONSIDERATION OF QUESTIONS UNDER THE COUNCIL’S RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE MAINTENANCE OF INTERNATIONAL PEACE AND SECURITY CONTENTS PrqpC INTRODUCTORYNME .............................. 97 PART I. ANALY~CAL TABLE OF MEASURES AWETED BY THE SECURITY GXJNCIL Note ................................... 97 PART II Situation in Viet-Nam ........................... 104 Complaint by the Government of Cyprus ................... I05 Situation in Southern Rhodesia ....................... 113 The Palestine question ........................... 124 Complaint by the United Kingdom ...................... 130 Complaint by the Democratic Republic of the Congo .............. 131 Situation in the Middle East (I) ....................... 134 Situation in the Middle East (II) ....................... 146 The question of South West Africa ...................... 164 Complaint by the United States (Pueblo incident). ............... 168 Complaint by Haiti ............................ 169 Question of safeguards to non-nuclear-weapon States parties to the Non-Proliferation Treaty ................................. 170 Situation in Czechoslovakia ......................... 171 ,-Y -2 INTRODUCTORY NOTE The principles underlying the organization and pre- consideration by the Council. With certain exceptions, sentation of the material presented in chapters VIII-XII a summary of the case presented to the Council is given of this Supplemenf are the same as for the previous at the outset of each question, together with a summary volumes of the Repertoire. Those volumes -

United Nations Juridical Yearbook, 1967

Extract from: UNITED NATIONS JURIDICAL YEARBOOK 1967 Part Four. Legal documents index and bibliography of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations Chapter IX. Legal documents index of the United Nations and related intergovernmental organizations Copyright (c) United Nations CONTENTS (continued) Page 9. Question whether the Office of Technical Co-operation has an obligation to disclose to Governments the cost of fellowships awarded to their nationals 329 10. Requirement of parity between administering and non-administering Powers within the Trusteeship Council under sub-paragraph 1 c. of Article 86 of the Charter-Question raised by Nauru's accession to independence. .... 330 11. Obligation under Article 102 of the Charter to register with the Secretariat treaties and international agreements entered into after the coming into force of the Charter-Question whether Article 102 also covers extensions of treaty inherited from a former colonial Power ............. 332 12. Question whether the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards of 10 June 1958 has been designed to supersede the International Convention on the Execution of Foreign Arbitral Awards of 26 September 1927 ......................... 334 13. Question whether the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, replaced as between parties to it the earlier narcotics treaties enumerated in para graph 1 of article 44 of the said Convention-Question whether the obliga- tions of these earlier treaties continue as between parties to them, -

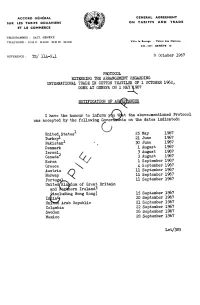

9 October 1967 PROTOCOL EXTENDING the ARRANGEMENT

ACCORD GÉNÉRAL GENERAL AGREEMENT SUR LES TARIFS DOUANIERS ON TARIFFS AND TRADE ET LE COMMERCE m TELEGRAMMES : GATT, GENÈVE TELEPHONE: 34 60 11 33 40 00 33 20 00 3310 00 Villa le Bocage - Palais des Nations CH-1211 GENÈVE tO REFERENCE : TS/ 114--5*! 9 October 1967 PROTOCOL EXTENDING THE ARRANGEMENT REGARDING INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN COTTON TEXTILES OF 1 OCTOBER 1962, DONE AT GENEVA ON 1 MAY U967 NOTIFICATION OF ACCEPTANCES I have the honour to inform yew. tHat the above-mentioned Protocol was accepted by the following Governments on the dates indicated: United States G 25 May 1967 Turkeys- 21 June 1967 Pakistan 30 June 1967 Denmark 1 August 1967 Israel, 3 August 1967 Canada* 3 August 1967 Korea 1 September 1967 Greece U September 1967 Austria 11 September 1967 Norway 11 September 1967 Portuga 11 Septembei• 1967 United/kinkdom of Great Britain and ItacAnern Ireland^ ^including Hong Kong) 15 September 1967 Irttia^ 20 September 1967 Unrtrea Arab Republic 21 September 1967 Colombia 22 September 1967 Sweden 26 September 1967 Mexico 28 September 1967 Let/385 - 2 - Republic of China 28 September 1967 Finland 29 September 1967 Belgium 29 September 1967 France 29 September 1967 Germany, Federal Republic 29 September 1967 Italy 29 September 1967 Luxemburg 29 September 1967 Netherlands, Kingdom of the (for its European territory only) 29 September 1967 Japan ,. 30 September 1967 Australia 30 September 1967 Jamaica 2 October 1967 Spain 3 October 1967 Acceptance by the Governments of Italy and of the Federal Republic of Germany was made subject to ratification. The Protocol entered into force on 1 October 1967, pursuant to its paragraph 5. -

Novacrat, November 1967 Nova University

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks The oN vacrat NSU Early Publications 11-1-1967 Novacrat, November 1967 Nova University Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_novacrat NSUWorks Citation Nova University, "Novacrat, November 1967" (1967). The Novacrat. 7. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_novacrat/7 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the NSU Early Publications at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Novacrat by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOVACRAT Official Publication Gold Key of Nova University Volume 1 - No.7 November 1967 SPEAKING OF EXPO-671 ANNUAL MEETING WITH "GOLD KEY - NOVA DR. GALLUP DECEMBER 1 UNIV. RENDEZVOUS" IS All is in re adiness fo r the GOLD KEY Annual Dinner meeting with Dr. George Gallup, founder-director of the REWARDING EVENT American Institute of Public Opinion. The Place: The Venetian Room GOLD KEY of Nova University attended Expo-67 . .. atop the Sheraton Hotel at 303 Canada 's One Hundredth Birthday Party _ . greatest of North Atlantic Boulevard, Fort all World Fairs . _ . along with General Charles de Gaulle, Lauderdale Beach. Emperor Haile Selassee, and assorted other heads of The Time: Cocktails at 6:30 p.m .; state, kings, princesses and important figures ... and dinner at 7:30 p.m., Friday, De some 50,00,000 more ordinary citizens of the world . cember l. Among the first and most lasting impressions were the Le Menu: Out of this world! ... courtesy, patience and good nature of most of the Cana from such aperities as Les Amuse dians! Who among the GOLD KEY-Nova U. -

Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States

Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States Period Median Average Jan 1963 $17,200 (NA) Feb 1963 $17,700 (NA) Mar 1963 $18,200 (NA) Apr 1963 $18,200 (NA) May 1963 $17,500 (NA) Jun 1963 $18,000 (NA) Jul 1963 $18,400 (NA) Aug 1963 $17,800 (NA) Sep 1963 $17,900 (NA) Oct 1963 $17,600 (NA) Nov 1963 $18,400 (NA) Dec 1963 $18,700 (NA) Jan 1964 $17,800 (NA) Feb 1964 $18,000 (NA) Mar 1964 $19,000 (NA) Apr 1964 $18,800 (NA) May 1964 $19,300 (NA) Jun 1964 $18,800 (NA) Jul 1964 $19,100 (NA) Aug 1964 $18,900 (NA) Sep 1964 $18,900 (NA) Oct 1964 $18,900 (NA) Nov 1964 $19,300 (NA) Dec 1964 $21,000 (NA) Jan 1965 $20,700 (NA) Feb 1965 $20,400 (NA) Mar 1965 $19,800 (NA) Apr 1965 $19,900 (NA) May 1965 $19,600 (NA) Jun 1965 $19,800 (NA) Jul 1965 $21,000 (NA) Aug 1965 $20,200 (NA) Sep 1965 $19,600 (NA) Oct 1965 $19,900 (NA) Nov 1965 $20,600 (NA) Dec 1965 $20,300 (NA) Jan 1966 $21,200 (NA) Feb 1966 $20,900 (NA) Mar 1966 $20,800 (NA) Apr 1966 $23,000 (NA) May 1966 $22,300 (NA) Jun 1966 $21,200 (NA) Jul 1966 $21,800 (NA) Aug 1966 $20,700 (NA) Sep 1966 $22,200 (NA) Oct 1966 $20,800 (NA) Nov 1966 $21,700 (NA) Dec 1966 $21,700 (NA) Jan 1967 $22,200 (NA) Page 1 of 13 Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States Period Median Average Feb 1967 $22,400 (NA) Mar 1967 $22,400 (NA) Apr 1967 $22,300 (NA) May 1967 $23,700 (NA) Jun 1967 $23,900 (NA) Jul 1967 $23,300 (NA) Aug 1967 $21,700 (NA) Sep 1967 $22,800 (NA) Oct 1967 $22,300 (NA) Nov 1967 $23,100 (NA) Dec 1967 $22,200 (NA) Jan 1968 $23,400 (NA) Feb 1968 $23,500 (NA) Mar 1968 -

USDOT) Opened and Began Operations in Washington, DC

April 1, 1967: The Opening Day of the U. S. On April 1, 1967, the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) opened and began operations in Washington, DC. This poster is Department of Transportation a story map of that day. A story map is a visualization tool that organizes text, maps, photos, and multimedia content to tell a story. David Martin, Reference Librarian, National Transportation Library The authors look at USDOT’s opening day through multiple lenses. Historical resources available in the USDOT, the National Archives Nicole Strayhorn, USDOT Intern & MLIS Candidate 2017, Florida State University and Records Administration, Washington DC historical collections, and other related sources are used to tell this story. A fully Amanda J. Wilson, Director, National Transportation Library Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting Poster P17-20768 interactive story map will be available from the NTL website (http://ntl.bts.gov) in Spring 2017. “Above all, we wish transportation to make a more positive contribution to the urban environment of this A crowd gathers at the National Mall to country. Assuredly, we want an end to the noise, pollution and general disfigurement it has watch a great, noisy, propeller driven vehicle unintentionally brought to our cities.” called a hydroskimmer. Alan S. Boyd, the 1st Secretary of the U.S. Department of Transportation Sources Carter, Elliot (2016). Map from WMATA. [online image] Retrieved November 4, 2016 from http://ggwash.org/ view/42784/these-metro-stations-names-used-to-be-very-different Posner, Gerald (2 April 1967). April Fools' happening opens new department. New York Times. Accessed October 19, A crowd watches as Alan S. -

Pdf Icon[PDF – 369

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION, AND WELFARE PUBLIC HEALTH SERVICE Health Services and Mental Health Ministration Washington D.C. 20201 VITAL STATISTICS REPORT HeaZkJJzterview SurveyDaiiz VOL. 18, NO. 9 FROM THE SUPPLEMENT I DECEMBER5, 1869 NATIONAL CENTER FOR HEALTH STATISTICS Cigarette Smoking Status-June 1966, August 1967, and August 1968 For the past 3 years the National Center for former smokers among males than among females, Health Statistics has contracted with the U.S. Bureau the proportion of female former cigarette smokers of the Census to include a supplement to the Current is increasing at a faster rate than that of males. From Population Survey on smoking habits in the United June 1966 to August 1968 the proportion of male former States. The first data were collected as a supplement smokers increased by 12 percent and the proportion of to the Current population Survey of June 1966, the female former smokers increased by 22 percent. In second supplement was added to the questionnaire in addition the increase occurred primarily among males August 1967, and the third in August 1968. Similar in the age group 17-24 years while it was spread data were collected during the period July 1964-July throughout all age categories for females. 1966 as a part of the ongoing Health Interview Sur In 1966 an estimated 39.6 percent of the population a vey. (See “Current Estimates from the Health Inter- aged 17 years and over smoked cigarettes; in 1968 the view Survey, United States, 1967,” Vital and Health comparable percentage was 37.7, a drop of 5 percent. -

WMO Bulletin, Volume XIII, No. 4: October 1964

WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION OCTOBER 1964 VOL.XIII N0.4 THE WORLD METEOROLOGICAL ORGANIZATION (WMO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations of which 124 States and Territories are Members It was created : - to facilitate international co-operation in the establishment of networks of stations and centres to provide meteorological services and observations to promote the establishment and maintenance of systems for the rapid exchange of meteorological information - to promote standardization of meteorological observations and ensure the uniform publication of observations and statistics to further the application of meteorology to aviation, shipping, agriculture and other human activities to encourage research and training in meteorology The World Meteorological Congress is the supreme body of the Organization. It brings together the delegates of all Members once every four years to determine general policies for the fulfilment of the purposes of the Organization The Executive Committee is composed of 21 directors of national meteorological services, and meets at least once a year to supervise the programme approved by Congress Six Regional Associations are each composed of Members whose task is to co-ordinate meteorological activities within their respective regions Eight Technical Commissions composed of experts designated by Members, are responsible for studying the special technical branches relating to meteorological observation, analysis, forecasting, research and the applications of meteorology EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President : Dr. A. NYBERG First Vice-President : Mr. L. DE AzcARRAGA Second Vice-President : Academician E. K. FEDOROV Regional Association presidents Africa (I) : Mr. RAMANISARIVO North and Central America (IV) : Asia (II) : Mr. S. N. NAQVI Ing. ELLIOTT COEN (acting) South America (III) : South-West Pacific (V) : Mr. -

BANK DEBITS T 16,19Ft and DEPOSIT TURNOVER

statist i(o release For immediate release BANK DEBITS T 16,19ft AND DEPOSIT TURNOVER Bank debits to demand deposit accounts, except interbank and U. S. Government accounts, as reported by "banks in 3^4 selected centers for the month of November aggregated $333*9 billion. During the past three months debits amounted to $1,026.4 billion or 8.7 per cent above the total reported for the corresponding period a year ago. At banks in New York City there was an increase of 10.6 per cent compared with the corresponding three-months period a year ago; at 6 other leading centers the increase was 4.3 per cent; and at 337 other centers it was 9.1 per cent. Seasonally adjusted debits to demand deposit accounts increased further in November to a level of $352.0 billion, but still remained slightly below the July peak. Changes at banks in New York City and 6 other leading centers were small and partially offsetting, but at 337 other centers, debits reached a new peak of $135-4 billion. The seasonally adjusted annual rate of turnover of demand deposits at 3^3 centers outside New York City remained unchanged at 35*5, a little below the April high but about 3-5 per cent higher than the October-November average last year. Total, Leading centers 337 Total, Leading centers 337 343 Period 344 other 344 other centers centers NYC 6 others * centers NYC 6 others* centers DEBITS To Demand Deposit Accounts ANNUAL RATE OF TURNOVER (In billions of dollars) Of Demand Deposits Not seasonally adjusted - November 296.6 116.7 63.8 116.1 43.6 8o.4 45.3 29.4 33-6 December -

Special Libraries, December 1967

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1967 Special Libraries, 1960s 12-1-1967 Special Libraries, December 1967 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1967 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, December 1967" (1967). Special Libraries, 1967. 10. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1967/10 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1967 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 4. u. Id speciar! libraries HUNGER.. INANITION. MARASMUS . whatever word you use, the problem is urgent. HOW TO PROVIDE FOOD FOR AN UNDERNOURISHED WORLD It is thoroughly discussed in the five volumes of the PROCEEDINGS OF THE VllTH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF NUTRITION, HAMBURG, GERMANY, AUGUST, 1966 Edited by JOACHIM K~JHNAU,University of productiori or inadequate use of available Munich and Hans-Dietrich Cremer, University of resources. In highly technical, highly civilized Giessen, both Germany. countries, too ample, often improperly bal- Volume i: NUTRITION and HEALTH anced diets will lead to problems of athero- sclerosis, high blood cholesterol levels, mal- Volume 2: REGULATION OF HUNGER -

Administrative Report for the Year Ending 30 June 1968 (To 15 May 1968)

RESTRICTED INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION FOR THE NORTHWEST ATLANTIC FISHERIES II ICNAF Comm.Doc.68/8 Serial No.2059 (A.b.l7) ANNUAL MEETING - JUNE 1968 Administrative Report for the Year ending 30 June 1968 (to 15 May 1968) 1. The Commission's Officers Chairman of Commission Mr V.M.Kamentsev (USSR) Vice-Chairman of Commission Dr A.W.H.Needler (Canada) Chairman of Panel 1 Mr O. Lund (Norway) Chairman of Panel 2 Mr W.e.Tame (UK) (to September 1967) Chairman of Panel 3 Dr F. Chrzan (Poland) Chairman of Panel 4 Captain T. de Almeida (Portugal) Chairman of Panel 5 Mr T.A.Fulham (USA) Chairman of Panel A (Seals) Dr A.W.H.Needler (Canada) These officers, with one exception, were elected at the 1967 Annual Meeting to serve for a period of two years. Dr A.W.H.Needler was elected Chairman of Panel A at the 1966 Annual Meeting to serve for a period of two years. Chairman of Standing Committee on Research and Statistics Nr Sv. Aa. Horsted (Denmark) Chairman of Standing Committee on Finance and Administration Mr R. Green (USA) Chairman of Standing Committee on Regulatory Measures Mr J. Graham (UK) The Chairmen of Research and Statistics and Finance and Administration were elected at the 1967 Annual Meeting to serve for a period of one year. The Chairman of the Standing Committee on Regulatory Measures was elected at the first meeting of the Committee, 30 January 1968. 2. Panel Memberships for 1967/68 (cf. ICNAF Camm.Doc.68fl) Panel .1 l. 1. .!!. .2. ! Total Canada + + + + + 5 Denmark + + 2 France + + + + 4 Germany + + 2 Iceland + 1 Italy + + 2 Norway + + 2 Poland + + + 3 Portugal + + + + 4 Romania + 1 Spain + + + + 4 USSR + + + + + 5 UK + + + 3 USA ;. -

Bring Me the Head of Frank Sinatra! Credit, and That He Keeps Three Loaded Double- in Early 1988

BRING ME THE HEAD OF FRANK “Old No. 6-7/8.” Screw those guys. Really. SINATRA! Jimmy's Bar Introduction If the group is already an adventuring party, then it stands to reason they will be in a tavern. If not, This is a module for 4-6 player characters of level well, they might as well meet at a tavern. 4-6. It is set in a gonzo post-apocalyptic past- Specifcally, Three-Arm Jimmy's, on the Hoboken future. waterfront. What that means, in practical terms, is that it is Three Arm Jimmy's is the sort of generic tavern set in the world presented in Gamma World or that unimaginative Game Masters always start Mutant Future (Encounter Critical could also easily modules in. It's got a bar, manned by Jimmy be used, although the setting is Earth, rather than himself—the extra arm comes in very handy for Vanth or Asteroid 1618). Statistics in this module pulling beers. The bar serves cheap but adequate will be given in Mutant Future terms. beer, a variety of rotgut liquors, most of which are nasty-ass industrial ethanol with a few drops of Other systems can be used, of course: since it favoring agents, and standard bar food, such as has been said that First Edition Gamma World salty deep-fried starchy things, onion rings, was the best edition of Dungeons and Dragons, pickled eggs, and the ubiquitous rat-on-a-stick D&D would work fne, as would Paranoia, Call of (show players Illustration #1). In addition to Cthulhu, Arduin, or an-only-slightly-variant Spawn Jimmy, there will be a waitress and a of Fashan, for instance.