The History of the Monastery of the Holy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Van Heijnsbergen, T. (2013) Coteries, Commendatory Verse and Jacobean Poetics: William Fowler's Triumphs of Petrarke and Its Castalian Circles

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten: Publications Van Heijnsbergen, T. (2013) Coteries, commendatory verse and Jacobean poetics: William Fowler's triumphs of Petrarke and its Castalian circles. In: Parkinson, D.J. (ed.) James VI and I, Literature and Scotland: Tides of Change, 1567-1625. Peeters Publishers, Leuven, Belgium, pp. 45- 63. ISBN 9789042926912 Copyright © 2013 Peeters Publishers A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge Content must not be changed in any way or reproduced in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder(s) When referring to this work, full bibliographic details must be given http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/69695/ Deposited on: 23 September 2013 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk James VI and I, Literature and Scotland Tides of Change, 1567-1625 EDITED BY David J. Parkinson PEETERS LEUVEN - PARIS - WALPOLE, MA 2013 CONTENTS Plates vii Abbreviations vii Note on Orthography, Dates and Currency vii Preface and Acknowledgements ix Introduction David J. Parkinson xi Contributors xv Shifts and Continuities in the Scottish Royal Court, 1580-1603 Amy L. Juhala 1 Italian Influences at the Court of James VI: The Case of William Fowler Alessandra Petrina 27 Coteries, Commendatory Verse and Jacobean Poetics: William Fowler's Trivmphs of Petrarke and its Castalian Circles Theo van Heijnsbergen 45 The Maitland -

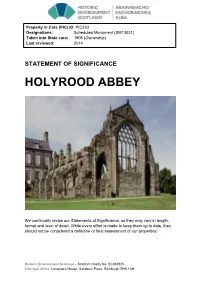

Holyrood Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC223 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13031) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HOLYROOD ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HOLYROOD ABBEY SYNOPSIS The Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was founded by David I in 1128 as a daughter-house of Merton Priory (Surrey). By the 15th century the abbey was increasingly being used as a royal residence – James II was born there in 1430 - and by the time of the Protestant Reformation (1560) much of the monastic precinct had been subsumed into the embryonic Palace of Holyroodhouse. -

Edinburgh Newsletter

April/June 2017 Edinburgh & West Lothian Services Edinburgh Newsletter Welcome to our Spring Newsletter When it’s spring again I’ll bring again tulips from Amsterdam. Well I don’t know about that but it is so good to see the light nights and daffodils, and feel a little bit of warmth. It’s that coming out of hibernation feeling. Some exciting things are happening, our Oasis group is returning to Holyrood Abbey Church (now Meadowbank Church) which is a positive move and the Forget Me Notes choir will be singing on Radio Forth for Dementia Awareness Week. Our Dementia Advisor for Edinburgh has recently retired and we wish Teresa all the very best. Teresa has worked for Alzheimer Scotland for nearly 20 years and has given amazing service within that time. We hope to appoint a new member of staff soon who will take on this role and we will introduce you to them when the recruitment process has been completed. If you would like to discuss anything with me I am on the end of the phone so don’t hesitate to give me a call. It is always good to step away from the computer and talk to people. Take Care Alan Service Manager Edinburgh, Mid & East Lothian Dementia Action Network Group The group met at the Quaker Meeting House in Edinburgh on the 3rd April. We had a presentation from a researcher looking at the challenges people can face getting out of their homes. We had a member of our technology team who was inviting people to be part of a trial for a relaxing virtual reality experience. -

Mary, Queen of Scots in Popular Culture

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Mary, Queen of Scots in Popular Culture Diplomová práce Bc. Gabriela Taláková Vedoucí diplomové práce: Mgr. Ema Jelínková, Ph.D. Olomouc 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne 28. 4. 2016 ..................................... Poděkování Na tomto místě bych chtěla poděkovat Mgr. Emě Jelínkové, Ph.D. za odborné vedení práce, poskytování rad a materiálových podkladů k diplomové práci, a také za její vstřícnost a čas. Content Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 1. Two Queens in One Isle ............................................................................................ 4 2. A Child Queen of Scotland ....................................................................................... 8 2.1 Historical Biographies ..................................................................................... 8 2.2 Fiction ............................................................................................................ 12 3. France ....................................................................................................................... 15 3.1 Mary and the Dauphin: A Marriage of Convenience? ................................... 15 3.1.1 Historical Biographies ....................................................................... 15 3.1.2 Fiction -

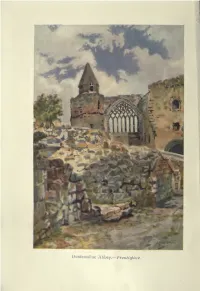

The Fringes of Fife

Uuniermline Ahh^y.—Frojitisptece. THE FRINGES OF FIFE NEW AND ENLARGED EDITION BY JOHN GEDDIE Author ot "The FiiniJes of Edinburjh," etc. Illustrated by Artliur Wall and Louis Weirter, R.B.A. LONDON: 38 Soto Square. W. 1 W. & R. CHAMBERS. LIMITED EDINBURGH: 339 High Street TO GEORGE A WATERS ' o{ the ' Scotsman MY GOOD COLLEAGUE DURING A QUARIER OF A CENTURY FOREWORD *I'll to ¥\ie:—Macl'eth. Much has happened since, in light mood and in light marching order, these walks along the sea- margin of Fife were first taken, some three-and-thirty years ago. The coasts of 'the Kingdom' present a surface hardened and compacted by time and weather —a kind of chequer-board of the ancient and the modern—of the work of nature and of man ; and it yields slowly to the hand of change. But here also old pieces have fallen out of the pattern and have been replaced by new pieces. Fife is not in all respects the Fife it was when, more than three decades ago, and with the towers of St Andrews beckoning us forward, we turned our backs upon it with a promise, implied if not expressed, and until now unfulfilled, to return and complete what had been begun. In the interval, the ways and methods of loco- motion have been revolutionised, and with them men's ideas and practice concerning travel and its objects. Pedestrianism is far on the way to go out of fashion. In 1894 the 'push-bike' was a compara- tively new invention ; it was not even known by the it was still name ; had ceased to be a velocipede, but a bicycle. -

Groups & Programmes for Parents and Carers

Information for Parents & Carers with Young Children in Leith & the North East of Edinburgh (Updated February 2015) Bookbug Sessions Bookbug sessions are free song, story and rhyme sessions for children 0-4 years and their parents/carers. There are regular Bookbug sessions in every library running throughout the year. Leith Library 1st and 3rd Tuesday of every month and 10.30-11.15am 2nd and 4th Wednesday of every month 10.30-11.15am McDonald Road Library Fridays 10.30-11am Mondays (Polish) 10.30-11am Stockbridge Library 1st and 3rd Tuesday of every month 10.30-11.15am Toy Library Casselbank Kids Toy Library T hursdays 9.30-12pm, term time South Leith Baptist Church, 5 Casselbank Street, EH6 5HA Tel: 07954 206 908 Parentline Free and confidential advice and support 08000 28 22 33 Spark Relationship Helpline Accessible telephone relationship counselling 0808 802 2088 Childminding Group A group for local childminders to meet with their minded children. Magdalene CC Gail McGregor Wed 9.30- 11.30 (as above) 07854 135 640 Playgroups (2.5yrs—5 yrs) A safe fun environment where you can leave your child to have fun and make friends. A cost is attached. Craigentinny Castle Playgroup Monday – Friday 9am-12pm Craigentinny Community Centre, 9 Loaning Road, Edinburgh Tel: 077254 84690 or 0131 661 8188 Drummond Community High School Crèche/ Playgroup Mon – Thu 9.30-11.30am/ 1-3pm/ Fri 9.30-11.30am, Tel: Crèche Manager on 0131 556 2651 Leith St Andrew’s Playgroup Monday – Friday 9.30-11.30am 410-412 Easter Road, EH6 8HTE, mail: [email protected] Parent and Toddler Groups A chance to meet other parents and carers and to have fun with your child. -

Thea Musgrave

SRCD.2369 STEREO AAD Thea Musgrave THEA MUSGRAVE Ashley Putnam Mary, Queen of Scots Jake Gardner Virginia Opera DISC ONE 53.28 Peter Mark 1 Cardinal Beaton’s Study 10.52 2 Mary’s arrival in Scotland 14.42 3 Peace Chorus 5.41 4 Ballroom at Holyrood 22.13 DISC TWO 79.11 1 Council Scene: Provocation Scene 18.21 2 Confrontation scene 13.03 3 Supper Room scene 6.41 4 Second Council scene 9.55 MARY 5 Opening - Mary’s Lullaby 11.04 6 Seduction scene 9.33 7 Mary’s Soliloquy. Finale 10.34 Total playing time 2 hours 12 minutes QUEEN OF SCOTS c 1979 issued under licence to Lyrita Recorded Edition from the copyright holder © 2018 Lyrita Recorded Edition, England. Lyrita is a registered trade mark. Made in the UK LYRITA RECORDED EDITION. Produced under an exclusive licence from Lyrita by Wyastone Estate Ltd, PO Box 87, Monmouth, NP25 3WX, UK SRCD 2369 20 SRCD 2369 1 Virginia Opera Production of Mary, Queen of Scots was made possible in part by grants from The Dalis Foundation The Virginia Commission of the Arts and Humanities The National Endowment for the Arts, a Federal Agency This recording of a live performance on 2 April, 1978 was made possible by the Martha Baird Rockefeller Fund for Music, Inc. and Maryanne Mott and Herman Warsh Recorded live in Norfolk, Virginia, at the gala performance for the Metropolitan Opera National Council’s Central Opera Service Conference and the Old Dominion University Institute of Scottish Studies Engineering and Production by Allen House In cooperation with The City of Norfolk and The Norfolk Department of Parks & Recreation Music published Novello Publications Inc., Ashley Putnam Photo: Virginia Opera © 1976 Novello & Co., Ltd. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. ‘Save Our Old Town’: Engaging developer-led masterplanning through community renewal in Edinburgh Christa B. Tooley PhD in Social Anthropology The University of Edinburgh 2012 (72,440 words) Declaration I declare that the work which has produced this thesis is entirely my own. This thesis represents my own original composition, which has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. __________________________________________________ Christa B. Tooley Abstract Through uneven processes of planning by a multiplicity of participants, Edinburgh’s built environment continues to emerge as the product of many competing strategies and projects of development. The 2005 proposal of a dramatic new development intended for an area of the city’s Old Town represents one such project in which many powerful municipal and commercial institutions are invested. -

U) ( \ ' Jf ( V \ ./ R *! Rj R I < F} 5 7 > | \ F * ( I | 1 < T M T 51 I 11 Ffi O [ ./: I1 T I'lloiiriv

U) ( \ ' Jf (\ ./v r *! r r ji < f} 5 7 > | \ f * ( i | 1 < t mt 51 i 11 ffi O [ ./: 1 t I I'llOiiriv '^y ■ ■; '/ k :}Kiy, ■ 7iK > v | National Library of Scotland illllllllllllllllllllillllllli *6000536714* Hfl2'2l3'D'/3gg' SCS.SH55. 511^54- SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY FIFTH SERIES VOLUME 19 Scottish Schools and Schoolmasters 1560-1633 Scottish Schools and Schoolmasters 1560-1633 t John Durkan Edited and revised by Jamie Reid-Baxter SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY 2006 THE BOYDELL PRESS © Scottish History Society 2013 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2013 A Scottish History Society publication in association with The Boydell Press an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620-2731, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com ISBN 978-0-906245-28-6 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library The publisher has no responsibility for the continued existence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Papers used by Boydell & Brewer Ltd are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in -

Seeing Europe with Famous Authors

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES GIFT OF WILLIAM P. WREDEN Yol. II SEEING EUROPE WITH FAMOUS ^. AUTHORS mm SELECTED AND EDITED Wfffp': WITH mm IXTRODUCTIONS, ETC. FRANCIS W. HALSEY Editor of "Creal Epochs in American History" Associate Editor of "The World's Famous Orations" and of "The Best of the World's Classics," etc. IN TEN .| VOLUMES ILLUSTRATED ® Vol. II GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND Part Two FUNK & WAGNALLS COMPANY NEW YORK AND LONDON Copyright, 1914, by FUNK & WAGNALLS COMPANY [Printed in the United States of Amerieal II V . CONTENTS OF VOLUME II Great Britain and Ireland—Part Two rV—ENGLISH LITERARY SHRINES— (Continued) PAGE Stoke Pogis—By Charles T. Congdon 1 Hawoeth—^By Theodore F. Wolfe 7 Gad's Hill—By Theodore F. Wolfe 14 Rydal Moukt—By William Howitt. 20 Twickenham—^By William Howitt 22 V—OTHER ENGLISH SCENES Stonehenge—By Ralph Waldo Emerson . 27 Magna Charta Island—By Mrs. S. C. Hall 30 The Home of the Pilgrim Fathers—^By James M. Hoppin 33 Oxford—^By Goldwin Smith 37 Cambridge—By James M. Hoppin 44 Chester—By Nathaniel Hawthorne .. .. 51 Eddystone Lighthouse—By Frederick A. Talbot 54 The Capital of the British^ Saxon and Norman Kings—By William Howitt . 61 V 611583 COiYIENTS VI—SCOTLAND PAGE Edinburgh—By Robert Louis Stevenson . 67 HOLYROOD—By David Masson 75 Linlithgow—By Sir Walter Scott .. .. 78 STiRiiiNG—By Nathaniel Hawthorne . 83 Abbotsford—By William Howitt 86 Dryburgh Abbey—By William Howitt. 92 Mehrose Abbey—By William Howitt . 98 Carlyle^s Birthplace and Early Homes— By John Burroughs 104 Burns's Land—By Nathaniel Hawthorne . -

THE THREE ARCHBISHOPS of the HOUSE of BETHUNE/BEATON! This Is a Paper Which Might Be About the Reformation in Scotland but It Is Not

29 THE THREE ARCHBISHOPS OF THE HOUSE OF BETHUNE/BEATON! This is a paper which might be about the Reformation in Scotland but it is not. I will not attempt in this paper to give an account of the opposition to the Reformation of Cardinal David Beaton which would require a separate paper. What I desire to do instead is to refer to the three Archbishops of the same family over a period of more than 100 years (1493 to 1603), as a background to some general points about power and influence in a society dominated by clans and families and some thoughts on the inextricable binding together of religion and politics in 16th century Scotland as an illustration of that binding together throughout the whole of Europe from much earlier times through to significantly later times. Scotland and the Scots retain today far more vestiges and survivals of the system of clan or family dependence and support than do most societies in which it occurred. The clan system or family alliances seems to have remained far stronger in Scotland by the 16th century than it was elsewhere in Europe though it was a well known phenomenon everywhere. Accordingly it is worth looking at why the Bethunes were a family of influence and note by the early 16th century. The first authentic reference to the family is found in 1165 about the end of the reign of William the Lion or the beginning of the reign of Alexander II. One Robert de Beton was witness to an important charter by Roger de Quincey then Constable of Scotland to Seyerus de Seton in relation to lands at Tranent. -

Souvenir of the Opening of the North British Station Hotel, Edinburgh

HHHbbsi Iras bSiss ran^ igbh MJHM8I Bjta^aPBMMWHi ffiffiflMff Hfflfl BlBlll««aaBa HB HSM9 MH UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH LIBRARY ! | | , iC'li'i 3 liafi 01P3Slb7 a UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH The Library SOCSCI DA 890- E 3 G19 Gedd i e , J ohn ., 1 848- 1 937 : Soli ve n i r o f t h e o p e n i n g o f the North Br i t i s>h St. at J. on Ho t el, Ed i nb u r g h NORTH BRITISH STATION HOTEL EDINBURGH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/souvenirofopeningedd SOUVENIR OF THE OPENING OF THE NORTH BRITISH STATION HOTEL EDINBURGH 15 th October 1902 CONTENTS- OLD AND NEW EDINBURGH NORTH BRITISH STATION HOTEL NORTH BRITISH RAILWAY Bv7 JOHN GEDDIE AUTHOR OF "Romantic Edinburgh" Printed by BANKS & CO. Grange Printing Works, EDINBURGH 1 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. OLD AND NI.W KDINBURGII. of ... ... Mary Queen Scots ... frontispiece The Tolbooth . Banks & Co. '9 View from Tower of North British Station Hotel Mercat ( !ross ... Banks cV Co. 20 ... —Looking West ... Banks & Co. 10 St Giles' ( lathedral Photo., John Patrick 2 1 View from Tower of North British Station Hotel Holyrood Palace . Photo., John Patrick 24 —Looking North-East . Banks 6" Co. i o Queen Mary's Bedroom, Holyrood Palace 27 Edinburgh Castle from Grassmarket Princes Street Looking West—View from North Banks cV Co. 1 British Station Hotel Photo., John Patrick 28 Edinburgh Castle from Esplanade Princes Street Gardens ... Photo., John Patrick 31 Photo., John Patrick 12 North British Station Hotel and Princes Street Banqueting Hall, Edinburgh Castle — Looking Hast ..