Medieval Window Glass in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

Dornochyou Can Do It All from Here

DornochYou can do it all from here The Highlands in miniature only 2 miles off the NC500 & one hour from Inverness Visit Dornoch, an historic Royal Burgh with a 13th century Cathedral, Castle, Jail & Courthouse in golden sandstone, all nestled round the green and Square where we hold summer markets and the pipe band plays on Saturday evenings. Things to do Historylinks Museum Historylinks Trail Discover 7,000 years of Explore the town through 16 Dornoch’s turbulent past in heritage sites with display our Visit Scotland 5 star panels. Pick up a leaflet and rated museum. map at the museum. Royal Dornoch Golf Club Dornoch Cathedral Golf has been played here for Gilbert de Moravia began over 400 years. building the Cathedral in 1224. The championship course is Following clan feuds it fell into rated #1 in Scotland and #4 in disrepair and was substantially the World by Golf Digest. restored in the 1800s. Aspen Spa Experience Dornoch & Embo Beaches Take some time out and relax Enjoy miles of unspoilt with a luxury spa, beauty beaches - ideal for making treatment or specialist golf sandcastles with the children massage. Gifts, beauty and spa or just walking the dog. products available in the shop. Events Calendar 2019 Car Boot Sales Community Markets The last Saturday of the month The 2nd Wednesday of the February, April, June, August month May to September, also & October fourth Wednesday June, July Dornoch Social Club & August. Cathedral Green 9:30 am - 12:30 pm 9:30 am - 1 pm Fibre Fest 8 - 10- March Dornoch Pipe Band Master classes, learning Parade on most Saturday techniques and drop in evenings from the 25th May to sessions. -

Cormack, Wade

UHI Thesis - pdf download summary Sport and Physical Education in the Northern Mainland Burghs of Scotland c. 1600-1800 Cormack, Wade DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (AWARDED BY OU/ABERDEEN) Award date: 2016 Awarding institution: The University of Edinburgh Link URL to thesis in UHI Research Database General rights and useage policy Copyright,IP and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the author, users must recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement, or without prior permission from the author. Users may download and print one copy of any thesis from the UHI Research Database for the not-for-profit purpose of private study or research on the condition that: 1) The full text is not changed in any way 2) If citing, a bibliographic link is made to the metadata record on the the UHI Research Database 3) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 4) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that any data within this document represents a breach of copyright, confidence or data protection please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Sport and Physical Education in the Northern Mainland Burghs of Scotland c. -

Teacher's Notes

Teacher’s notes | 1 | | HISTORYLINKS SCHOOLPACKS - SECONDARY | Teacher’s notes | HISTORYLINKS SCHOOLPACKS | have been produced to provide S1 and S2 pupils with an understanding of the history of the Royal Burgh of Dornoch from the 13th century to the present day. There are four packs dealing with the following themes: Dornoch Cathedral Health & Sanitation Crime & Punishment Markets & Trade They aim to fit in with the 5-14 National Guidelines for Environmental Studies, specifically for Social Subjects, People in the Past. The strands covered include Change and Continuity, Cause and Effect; Time and Historical Sequence; The Nature of Historical Evidence. It is hoped that by visiting specific sites in Dornoch and completing the tasks on the worksheets, pupils will develop a knowledge and understanding of a number of historical developments that took place over the centuries in this small Highland town. | HISTORYLINKS SCHOOLPACKS | Teacher’s notes | 2 | Orientation information In order to help you plan your visit to Dornoch each schoolpack includes a copy of the Dornoch Historylinks Trail leaflet showing the main locations of historical interest located in the town. At most of these sites there is an interpretation board with further information. Not all the locations mentioned in the worksheets still exist today, but a number of those that do remain are well worthwhile visiting. The Historylinks Trail leaflet provides numbered locations of those sites, and the relevant ones for each of the four schoolpacks are indicated below. Dornoch Cathedral This site is only too obvious, but in addition to the Cathedral itself students may wish to look at sites (2) The Old Parish Manse and (5), the Monastery Well. -

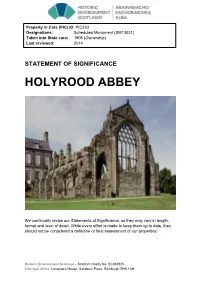

Holyrood Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC223 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13031) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HOLYROOD ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HOLYROOD ABBEY SYNOPSIS The Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was founded by David I in 1128 as a daughter-house of Merton Priory (Surrey). By the 15th century the abbey was increasingly being used as a royal residence – James II was born there in 1430 - and by the time of the Protestant Reformation (1560) much of the monastic precinct had been subsumed into the embryonic Palace of Holyroodhouse. -

Edinburgh Newsletter

April/June 2017 Edinburgh & West Lothian Services Edinburgh Newsletter Welcome to our Spring Newsletter When it’s spring again I’ll bring again tulips from Amsterdam. Well I don’t know about that but it is so good to see the light nights and daffodils, and feel a little bit of warmth. It’s that coming out of hibernation feeling. Some exciting things are happening, our Oasis group is returning to Holyrood Abbey Church (now Meadowbank Church) which is a positive move and the Forget Me Notes choir will be singing on Radio Forth for Dementia Awareness Week. Our Dementia Advisor for Edinburgh has recently retired and we wish Teresa all the very best. Teresa has worked for Alzheimer Scotland for nearly 20 years and has given amazing service within that time. We hope to appoint a new member of staff soon who will take on this role and we will introduce you to them when the recruitment process has been completed. If you would like to discuss anything with me I am on the end of the phone so don’t hesitate to give me a call. It is always good to step away from the computer and talk to people. Take Care Alan Service Manager Edinburgh, Mid & East Lothian Dementia Action Network Group The group met at the Quaker Meeting House in Edinburgh on the 3rd April. We had a presentation from a researcher looking at the challenges people can face getting out of their homes. We had a member of our technology team who was inviting people to be part of a trial for a relaxing virtual reality experience. -

Groups & Programmes for Parents and Carers

Information for Parents & Carers with Young Children in Leith & the North East of Edinburgh (Updated February 2015) Bookbug Sessions Bookbug sessions are free song, story and rhyme sessions for children 0-4 years and their parents/carers. There are regular Bookbug sessions in every library running throughout the year. Leith Library 1st and 3rd Tuesday of every month and 10.30-11.15am 2nd and 4th Wednesday of every month 10.30-11.15am McDonald Road Library Fridays 10.30-11am Mondays (Polish) 10.30-11am Stockbridge Library 1st and 3rd Tuesday of every month 10.30-11.15am Toy Library Casselbank Kids Toy Library T hursdays 9.30-12pm, term time South Leith Baptist Church, 5 Casselbank Street, EH6 5HA Tel: 07954 206 908 Parentline Free and confidential advice and support 08000 28 22 33 Spark Relationship Helpline Accessible telephone relationship counselling 0808 802 2088 Childminding Group A group for local childminders to meet with their minded children. Magdalene CC Gail McGregor Wed 9.30- 11.30 (as above) 07854 135 640 Playgroups (2.5yrs—5 yrs) A safe fun environment where you can leave your child to have fun and make friends. A cost is attached. Craigentinny Castle Playgroup Monday – Friday 9am-12pm Craigentinny Community Centre, 9 Loaning Road, Edinburgh Tel: 077254 84690 or 0131 661 8188 Drummond Community High School Crèche/ Playgroup Mon – Thu 9.30-11.30am/ 1-3pm/ Fri 9.30-11.30am, Tel: Crèche Manager on 0131 556 2651 Leith St Andrew’s Playgroup Monday – Friday 9.30-11.30am 410-412 Easter Road, EH6 8HTE, mail: [email protected] Parent and Toddler Groups A chance to meet other parents and carers and to have fun with your child. -

SUTHERLAND Reference to Parishes Caithness 1 Keay 6 J3 2 Thurso 7 Wick 3 Olrig 8 Waiter 4 Dunnet 9 Sauark 5 Canisbay ID Icajieran

CO = oS BRIDGE COUNTY GEOGRAPHIES -CD - ^ jSI ;co =" CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND Reference to Parishes Caithness 1 Keay 6 J3 2 Thurso 7 Wick 3 Olrig 8 Waiter 4 Dunnet 9 SaUark 5 Canisbay ID IcaJieran. Sutherland Durnesx 3 Tatujue 4 Ibrr 10 5 Xildsjnan 11 6 LoiK 12 CamJbriA.gt University fi PHYSICAL MAP OF CAITHNESS & SUTHERLAND Statute Afiie* 6 Copyright George FkOip ,6 Soni ! CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS C. F. CLAY, MANAGER LONDON : FETTER LANE, E.C. 4 NEW YORK : THE MACMILLAN CO. BOMBAY | CALCUTTA !- MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD. MADRAS J TORONTO : THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, LTD. TOKYO : MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND by H. F. CAMPBELL M.A., B.L., F.R.S.G.S. Advocate in Aberdeen With Maps, Diagrams, and Illustrations CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1920 Printed in Great Britain ly Turnbull &* Spears, Edinburgh CONTENTS CAITHNESS PACK 1. County and Shire. Origin and Administration of Caithness ...... i 2. General Characteristics .... 4 3. Size. Shape. Boundaries. Surface . 7 4. Watershed. Rivers. Lakes . 10 5. Geology and Soil . 12 6. Natural History 19 Coast Line 7. ....... 25 8. Coastal Gains and Losses. Lighthouses . 27 9. Climate and Weather . 29 10. The People Race, Language, Population . 33 11. Agriculture 39 12. Fishing and other Industries .... 42 13. Shipping and Trade ..... 44 14. History of the County . 46 15. Antiquities . 52 1 6. Architecture (a) Ecclesiastical . 61 17. Architecture (6) Military, Municipal, Domestic 62 1 8. Communications . 67 19. Roll of Honour 69 20. Chief Towns and Villages of Caithness . 73 vi CONTENTS SUTHERLAND PAGE 1. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. ‘Save Our Old Town’: Engaging developer-led masterplanning through community renewal in Edinburgh Christa B. Tooley PhD in Social Anthropology The University of Edinburgh 2012 (72,440 words) Declaration I declare that the work which has produced this thesis is entirely my own. This thesis represents my own original composition, which has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. __________________________________________________ Christa B. Tooley Abstract Through uneven processes of planning by a multiplicity of participants, Edinburgh’s built environment continues to emerge as the product of many competing strategies and projects of development. The 2005 proposal of a dramatic new development intended for an area of the city’s Old Town represents one such project in which many powerful municipal and commercial institutions are invested. -

U) ( \ ' Jf ( V \ ./ R *! Rj R I < F} 5 7 > | \ F * ( I | 1 < T M T 51 I 11 Ffi O [ ./: I1 T I'lloiiriv

U) ( \ ' Jf (\ ./v r *! r r ji < f} 5 7 > | \ f * ( i | 1 < t mt 51 i 11 ffi O [ ./: 1 t I I'llOiiriv '^y ■ ■; '/ k :}Kiy, ■ 7iK > v | National Library of Scotland illllllllllllllllllllillllllli *6000536714* Hfl2'2l3'D'/3gg' SCS.SH55. 511^54- SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY FIFTH SERIES VOLUME 19 Scottish Schools and Schoolmasters 1560-1633 Scottish Schools and Schoolmasters 1560-1633 t John Durkan Edited and revised by Jamie Reid-Baxter SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY 2006 THE BOYDELL PRESS © Scottish History Society 2013 All rights reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner First published 2013 A Scottish History Society publication in association with The Boydell Press an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Ltd PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK and of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620-2731, USA website: www.boydellandbrewer.com ISBN 978-0-906245-28-6 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library The publisher has no responsibility for the continued existence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Papers used by Boydell & Brewer Ltd are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in -

Dornoch Cathedral Windows

DORNOCH CATHEDRAL WINDOWS These notes are for the many people who not only comment on the beauty of the Cathedral windows, but who may like to learn, briefly, their background, and those commemorated in them. The Cathedral was extensively altered and rebuilt by Elizabeth, Duchess Countess of Sutherland from 1835 – 1837. Those windows remaining before work were all restored or replaced in the design of Alexander Coupar. THE CHANCEL North Wall of the Chancel Three windows by Percy C. Bacon, of London, 1926, erected in memory of Andrew Carnegie (1898-1919 owner of Skibo Castle, and benefactor of this Cathedral). The subjects [from left to right] represent Carnegie’s interests in Literature, Peace and Music. Literature is represented by a woman holding a book with two crossed torches of learning at her feet. At the apex is an angel also holding a book “A Light unto my Faith”. Peace is depicted by Christ with the words “Blessed are the Peacemakers” below which the Angel appears to the shepherds proclaiming “On Earth Peace, Goodwill to men”. Music is represented by a female figure holding a musical instrument with crossed instruments at her feet and an angel holding a sheet of music over her head. The inscriptions read:- A Light unto my faith Blessed are the peacemakers Praise be the Lord Let there be Light On earth peace, goodwill toward men To the Glory of God loving memory of Skibo and in of Andrew Carnegie 1835 - 1919 East Gable of the Chancel These are by Christopher Whall (1849-1924) of London, and commemorate Cromartie, 4th Duke of Sutherland (1851-1913). -

Souvenir of the Opening of the North British Station Hotel, Edinburgh

HHHbbsi Iras bSiss ran^ igbh MJHM8I Bjta^aPBMMWHi ffiffiflMff Hfflfl BlBlll««aaBa HB HSM9 MH UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH LIBRARY ! | | , iC'li'i 3 liafi 01P3Slb7 a UNIVERSITY OF GUELPH The Library SOCSCI DA 890- E 3 G19 Gedd i e , J ohn ., 1 848- 1 937 : Soli ve n i r o f t h e o p e n i n g o f the North Br i t i s>h St. at J. on Ho t el, Ed i nb u r g h NORTH BRITISH STATION HOTEL EDINBURGH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/souvenirofopeningedd SOUVENIR OF THE OPENING OF THE NORTH BRITISH STATION HOTEL EDINBURGH 15 th October 1902 CONTENTS- OLD AND NEW EDINBURGH NORTH BRITISH STATION HOTEL NORTH BRITISH RAILWAY Bv7 JOHN GEDDIE AUTHOR OF "Romantic Edinburgh" Printed by BANKS & CO. Grange Printing Works, EDINBURGH 1 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. OLD AND NI.W KDINBURGII. of ... ... Mary Queen Scots ... frontispiece The Tolbooth . Banks & Co. '9 View from Tower of North British Station Hotel Mercat ( !ross ... Banks cV Co. 20 ... —Looking West ... Banks & Co. 10 St Giles' ( lathedral Photo., John Patrick 2 1 View from Tower of North British Station Hotel Holyrood Palace . Photo., John Patrick 24 —Looking North-East . Banks 6" Co. i o Queen Mary's Bedroom, Holyrood Palace 27 Edinburgh Castle from Grassmarket Princes Street Looking West—View from North Banks cV Co. 1 British Station Hotel Photo., John Patrick 28 Edinburgh Castle from Esplanade Princes Street Gardens ... Photo., John Patrick 31 Photo., John Patrick 12 North British Station Hotel and Princes Street Banqueting Hall, Edinburgh Castle — Looking Hast ..