Status Overview and Recommendations for Conservation of the White-Headed Duck in Central Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Rivers of Mongolia

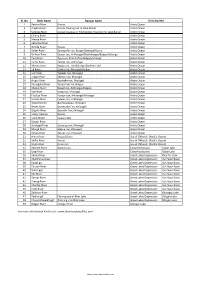

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Ramsar Sites in Order of Addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance

Ramsar sites in order of addition to the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance RS# Country Site Name Desig’n Date 1 Australia Cobourg Peninsula 8-May-74 2 Finland Aspskär 28-May-74 3 Finland Söderskär and Långören 28-May-74 4 Finland Björkör and Lågskär 28-May-74 5 Finland Signilskär 28-May-74 6 Finland Valassaaret and Björkögrunden 28-May-74 7 Finland Krunnit 28-May-74 8 Finland Ruskis 28-May-74 9 Finland Viikki 28-May-74 10 Finland Suomujärvi - Patvinsuo 28-May-74 11 Finland Martimoaapa - Lumiaapa 28-May-74 12 Finland Koitilaiskaira 28-May-74 13 Norway Åkersvika 9-Jul-74 14 Sweden Falsterbo - Foteviken 5-Dec-74 15 Sweden Klingavälsån - Krankesjön 5-Dec-74 16 Sweden Helgeån 5-Dec-74 17 Sweden Ottenby 5-Dec-74 18 Sweden Öland, eastern coastal areas 5-Dec-74 19 Sweden Getterön 5-Dec-74 20 Sweden Store Mosse and Kävsjön 5-Dec-74 21 Sweden Gotland, east coast 5-Dec-74 22 Sweden Hornborgasjön 5-Dec-74 23 Sweden Tåkern 5-Dec-74 24 Sweden Kvismaren 5-Dec-74 25 Sweden Hjälstaviken 5-Dec-74 26 Sweden Ånnsjön 5-Dec-74 27 Sweden Gammelstadsviken 5-Dec-74 28 Sweden Persöfjärden 5-Dec-74 29 Sweden Tärnasjön 5-Dec-74 30 Sweden Tjålmejaure - Laisdalen 5-Dec-74 31 Sweden Laidaure 5-Dec-74 32 Sweden Sjaunja 5-Dec-74 33 Sweden Tavvavuoma 5-Dec-74 34 South Africa De Hoop Vlei 12-Mar-75 35 South Africa Barberspan 12-Mar-75 36 Iran, I. R. -

Report of the Portfolio Monitoring Mission in Mongolia

AFB/B.28/5 3 October 2016 Adaptation Fund Board Twenty-eighth Meeting Bonn, Germany, 6-7 October 2016 Agenda item 9 REPORT OF THE PORTFOLIO MONITORING MISSION IN MONGOLIA AFB/B.28/5 INTRODUCTION Context and scope of the mission 1. As part of the Knowledge Management (KM) Strategy and the secretariat’s work plan for FY16 which was approved by the Adaptation Fund Board (the Board) at its twenty-fifth meeting (Decision B.25/19), the Adaptation Fund Board secretariat (the secretariat) conducts missions to projects/programmes under implementation to collect and analyze lessons learned through its portfolio. So far, such missions have been conducted in Ecuador, Senegal, Honduras, Nicaragua, Jamaica, Argentina and Uruguay. This report covers the FY16 portfolio monitoring mission that took place in June 2016 in the project “Ecosystem Based Adaptation Approach to Maintaining Water Security in Critical Water Catchments in Mongolia” implemented by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2. The mission targeted this project for the following reasons: a) it enables to explore implications of the Ecosystem-Based Adaptation (EBA) approach, including its efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability; b) it may allow drawing lessons from the valuation of ecosystem services; c) it may allow taking stock of the arrangements for monitoring and evaluation, and the value of mid-term review in adjusting progress towards results. Methodology 3. The secretariat was represented by a senior climate change specialist and a junior professional associate. An Adaptation Fund Board alternate member was also part of the delegation. The mission was carried out from 12 to 18 June, and included field visits to project sites. -

Living Lakes Goals 2019 - 2024 Achievements 2012 - 2018

Living Lakes Goals 2019 - 2024 Achievements 2012 - 2018 We save the lakes of the world! 1 Living Lakes Goals 2019-2024 | Achievements 2012-2018 Global Nature Fund (GNF) International Foundation for Environment and Nature Fritz-Reichle-Ring 4 78315 Radolfzell, Germany Phone : +49 (0)7732 99 95-0 Editor in charge : Udo Gattenlöhner Fax : +49 (0)7732 99 95-88 Coordination : David Marchetti, Daniel Natzschka, Bettina Schmidt E-Mail : [email protected] Text : Living Lakes members, Thomas Schaefer Visit us : www.globalnature.org Graphic Design : Didem Senturk Photographs : GNF-Archive, Living Lakes members; Jose Carlo Quintos, SCPW (Page 56) Cover photo : Udo Gattenlöhner, Lake Tota-Colombia 2 Living Lakes Goals 2019-2024 | Achievements 2012-2018 AMERICAS AFRICA Living Lakes Canada; Canada ........................................12 Lake Nokoué, Benin .................................................... 38 Columbia River Wetlands; Canada .................................13 Lake Ossa, Cameroon ..................................................39 Lake Chapala; Mexico ..................................................14 Lake Victoria; Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda ........................40 Ignacio Allende Reservoir, Mexico ................................15 Bujagali Falls; Uganda .................................................41 Lake Zapotlán, Mexico .................................................16 I. Lake Kivu; Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda 42 Laguna de Fúquene; Colombia .....................................17 II. Lake Kivu; Democratic -

Key Sites for Key Sites for Conservation

Directory of Important Bird Areas in Mongolia: KEY SITES FOR CONSERVATION A project of In collaboration with With the support of Printing sponsored by Field surveys supported by Directory of Important Bird Areas in Mongolia: KEY SITES FOR CONSERVATION Editors: Batbayar Nyambayar and Natsagdorj Tseveenmyadag Major contributors: Ayurzana Bold Schagdarsuren Boldbaatar Axel Bräunlich Simba Chan Richard F. A. Grimmett and Andrew W. Tordoff This document is an output of the World Bank study Strengthening the Safeguard of Important Areas of Natural Habitat in North-East Asia,fi nanced by consultant trust funds from the government of Japan Ulaanbaatar, January 2009 An output of: The World Bank study Strengthening the Safeguard of Important Areas of Natural Habitat in North-East Asia,fi nanced by consultant trust funds from the government of Japan Implemented by: BirdLife International, the Wildlife Science and Conservation Center and the Institute of Biology of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences In collaboration with: Ministry of Nature, Environment and Tourism Supporting organisations: WWF Mongolia, WCS Mongolia Program and the National University of Mongolia Editors: Batbayar Nyambayar and Natsagdorj Tseveenmyadag Major contributors: Ayurzana Bold, Schagdarsuren Boldbaatar, Axel Bräunlich, Simba Chan, Richard F. A. Grimmett and Andrew W. Tordoff Maps: Dolgorjav Sanjmyatav, WWF Mongolia Cover illustrations: White-naped Crane Grus vipio, Dalmatian Pelican Pelecanus crispus, Whooper Swans Cygnus cygnus and hunters with Golden Eagles Aquila chrysaetos (Batbayar Nyambayar); Siberian Cranes Grus leucogeranus (Natsagdorj Tseveenmyadag); Saker Falcons Falco cherrug and Yellow-headed Wagtail Motacilla citreola (Gabor Papp). ISBN: 978-99929-0-752-5 Copyright: © BirdLife International 2009. All rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged Suggested citation: Nyambayar, B. -

2007 UNEP-WCMC Global List of Transboundary Protected Areas Lysenko I., Besançon C., Savy C

2007 UNEP-WCMC Global List of Transboundary Protected Areas Lysenko I., Besançon C., Savy C. No TBPA Name Country Protected Areas Sitecode Category PA Size, km 2 TBPA Area, km 2 Ellesmere/Greenland 1 Canada Quttinirpaaq 300093 II 38148.00 Transboundary Complex Greenland Hochstetter Forland 67910 RAMSAR 1848.20 Kilen 67911 RAMSAR 512.80 North-East Greenland 2065 MAB-BR 972000.00 North-East Greenland 650 II 972000.00 1,008,470.17 2 Canada Ivvavik 100672 II 10170.00 Old Crow Flats 101594 IV 7697.47 Vuntut 100673 II 4400.00 United States Arctic 2904 IV 72843.42 Arctic 35361 Ia 32374.98 Yukon Flats 10543 IV 34925.13 146,824.27 Alaska-Yukon-British Columbia 3 Canada Atlin 4178 II 2326.95 Borderlands Atlin 65094 II 384.45 Chilkoot Trail Nhp 167269 Unset 122.65 Kluane 612 II 22015.00 Kluane Wildlife 18707 VI 6450.00 Kluane/Wrangell-St Elias/Glacier Bay/Tatshenshini-Alsek 12200 WHC 31595.00 Tatshenshini-Alsek 67406 Ib 9470.26 United States Admiralty Island 21243 Ib 3803.76 Chilkat 68395 II 24.46 Chilkat Bald Eagle 68396 II 198.38 Glacier Bay 1010 II 13045.50 Glacier Bay 22485 V 233.85 Glacier Bay 35382 Ib 10784.27 Glacier Bay-Admiralty Island Biosphere Reserve 11591 MAB-BR 15150.15 Kluane/Wrangell-St Elias/Glacier Bay/Tatshenshini-Alsek 2018 WHC 66796.48 Kootznoowoo 101220 Ib 3868.24 Malaspina Glacier 21555 III 3878.40 Mendenhall River 306286 Unset 14.57 Misty Fiords 21247 Ib 8675.10 Misty Fjords 13041 IV 4622.75 Point Bridge 68394 II 11.64 Russell Fiord 21249 Ib 1411.15 Stikine-LeConte 21252 Ib 1816.75 Tetlin 2956 IV 2833.07 Tongass 13038 VI 67404.09 Global List of Transboundary Protected Areas ©2007 UNEP-WCMC 1 of 78 No TBPA Name Country Protected Areas Sitecode Category PA Size, km 2 TBPA Area, km 2 Tracy Arm-Fords Terror 21254 Ib 2643.43 Wrangell-St Elias 1005 II 33820.14 Wrangell-St Elias 35387 Ib 36740.24 Wrangell-St. -

Hippophae Rhamnoides L.)

International Journal for Research in Agricultural and Food Science ISSN: 2208-2719 Study result of Mongolian natural wild seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) 1Oyungerel.D, 1Bayaraa,G, 1Battumur.S, 1Altangoo.G, 2Nasanjargal.D,1 Gantuya.D, 1Otgontamir Ts. 1 Oyungerel Dechinlkhundev, Head of Fruit and Ornamental Plant Research Division, Institute of Plant and Agricultural Sciences,IPAS. P.O.Box-908,Darkhan-Uul- 45047,Mongolia 2Nasanjargal Darjaa, Mongolian National Association of Fruit and Berry.Ulaanbaatar city, Sukhbaatar district 1th Khoroo, Peace avenue 50, Azmon center,room number 503,Mongolia Abstract Seabuckthorn sub specie (Hippophae rhamnoides L. ssp mongolica Rous.) is distributed in confluence of Orkhon-Selenge and basins of Zavkhan Tes, Uvs Tes, Bukhmurun, Tortkhilog Buyant, Khovd, Zavkhan, Borkh and Bulgan rivers. Natural wild seabuckthorn’s permanent distribution is in the western part of Mongolia’s mountainous region of Altai, Khangai and at the Tes, Zavkhan and Khovd rivers with internal flow to Great Lake concave, which starts from Altai and Khangai ranges’ branch mountains and at the Bulgan and other rivers’ valley, which have an external flow. By natural and weather condition, Bulgan aimag is located in humid cool, Selenge aimag is in arid cool, Zavkhan aimag is in arid coolish, Govi-Altai and Khovd aimags are in very arid, Uvs aimag is in arid cool region, respectively. Soil humus was in 0-20 sm depth 1.1-2.3%, 20-40 sm depth 0.6-1.7% at the research area. Soil of Zavkhan river basin had lowest humus content (0.76-1.2%), this includes Mongolian sand area and areas with sandy soil. -

Climate Change

This “Mongolia Second Assessment Report on Climate Change 2014” (MARCC 2014) has been developed and published by the Ministry of Environment and Green Development of Mongolia with financial support from the GIZ programme “Biodiversity and adaptation of key forest ecosystems to climate change”, which is being implemented in Mongolia on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development. Copyright © 2014, Ministry of Environment and Green Development of Mongolia Editors-in-chief: Damdin Dagvadorj Zamba Batjargal Luvsan Natsagdorj Disclaimers This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part in any form for educational or non-profit services without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The Ministry of Environment and Green Development of Mongolia would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Ministry of Environment and Green Development of Mongolia. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures . 3 List of Tables . .. 12 Abbreviations . 14 Units . 17 Foreword . 19 Preface . 22 1. Introduction. Batjargal Z. 27 1.1 Background information about the country . 33 1.2 Introductory information on the second assessment report-MARCC 2014 . 31 2. Climate change: observed changes and future projection . 37 2.1 Global climate change and its regional and local implications. Batjargal Z. 39 2.1.1 Observed global climate change as estimated within IPCC AR5 . 40 2.1.2 Temporary slowing down of the warming . 43 2.1.3 Driving factors of the global climate change . -

Mongolian Vision Tours

Mongolian Vision Tours FROM DESERT TO STEPPE Nomadic Mongolia waits for you in this tour in the heart of the nomadic life. From family to family, you will start your horse trek tour by the green Orkhon Valley, before going deeper in the remote area of Naiman Nuur. Then you'll go towards South, where the track disappears to give place to a legendary spot: the Gobi Desert, and the arid majesty of its lunar landscapes, with its towering rocky formations, frozen canyon and sand dunes. Day1. The granite formations of Baga Gazriin Chuluu Ulan Bator – Baga Gazriin Chuluu 250km Visit of Mountains Baga Gazriin Chuluu, where we'll observe stunning granite rock formations eroded by the violent elements of this area. In the 19th century, two respected lamas lived here, and we still can see their inscriptions in the rock. According to the legend, Genghis Khan to is supposed to have lived in this wonderful area where it's pleasant to walk. Stay overnight: Nomadic Family’s ger or tourist ger camp Day2. The great white stupa in the desert Baga Gazar Chuluu – white stupa 220km We travel in one of the emptiest areas of Mongolia. Between rock desert and semi-arid steppes, we reach the white stupa, Tsagaan Suvarga. For centuries, this 30-metre (98,43 feet) high, abrupt, stupa- shaped mountain, is honored by the Mongolians. The traveler will be surprised by the sumptuous lunar landscapes that evoke the end of the world, and by the many fossils. This area was totally covered by the sea a few million years ago. -

Tuul River Mongolia

HEALTHY RIVERS FOR ALL Tuul River Basin Report Card • 1 TUUL RIVER MONGOLIA BASIN HEALTH 2019 REPORT CARD Tuul River Basin Report Card • 2 TUUL RIVER BASIN: OVERVIEW The Tuul River headwaters begin in the Lower As of 2018, 1.45 million people were living within Khentii mountains of the Khan Khentii mountain the Tuul River basin, representing 46% of Mongolia’s range (48030’58.9” N, 108014’08.3” E). The river population, and more than 60% of the country’s flows southwest through the capital of Mongolia, GDP. Due to high levels of human migration into Ulaanbaatar, after which it eventually joins the the basin, land use change within the floodplains, Orkhon River in Orkhontuul soum where the Tuul lack of wastewater treatment within settled areas, River Basin ends (48056’55.1” N, 104047’53.2” E). The and gold mining in Zaamar soum of Tuv aimag and Orkhon River then joins the Selenge River to feed Burenkhangai soum of Bulgan aimag, the Tuul River Lake Baikal in the Russian Federation. The catchment has emerged as the most polluted river in Mongolia. area is approximately 50,000 km2, and the river itself These stressors, combined with a growing water is about 720 km long. Ulaanbaatar is approximately demand and changes in precipitation due to global 470 km upstream from where the Tuul River meets warming, have led to a scarcity of water and an the Orkhon River. interruption of river flow during the spring. The Tuul River basin includes a variety of landscapes Although much research has been conducted on the including mountain taiga and forest steppe in water quality and quantity of the Tuul River, there is the upper catchment, and predominantly steppe no uniform or consistent assessment on the state downstream of Ulaanbaatar City. -

Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 193 (2019) 105427

Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 193 (2019) 105427 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsbmb Comparison of seasonal serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations among T pregnant women in Mongolia and Boston Sabri Bromagea,b, Davaasambuu Enkhmaac, Tsedmaa Baatard, Gantsetseg Garmaab, Gary Bradwine, Buyandelger Yondonsambuuf, Tuul Sengeeg, Enkhtuya Jamtsc, Narmandakh Suldsurend, Thomas F. McElrathh, David E. Cantonwineh, Robert N. Hooveri, ⁎ Rebecca Troisii, Davaasambuu Ganmaaa,b,j, a Department of Nutrition, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, 665 Huntington Avenue, SPH-2 Floor 3, Boston, MA, 02115, USA b Mongolian Health Initiative Non-Governmental Organization, Bayanzurkh District, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia c National Center for Maternal and Child Health, Khuvisgalchdin Street, Bayangol District, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia d United Nations Population Fund Mongolia Country Office, 14 United Nations Street, Sukhbaatar District, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia e Department of Laboratory Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA, 02115, USA f Mandal Soum Hospital, Mandal Soum, Selenge, Mongolia g Bayangol District Hospital, Bayangol District, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia h Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, MA, 02115, USA i Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Institutes of Health, 9609 Medical Center Drive, MSC 9776, Bethesda, MD, 20892, USA j Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, 181 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA, 02115, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Adequate vitamin D status during pregnancy is important for developing fetal bone strength and density and Vitamin D deficiency may play a role in preventing a range of skeletal and non-skeletal diseases in both mothers and children. -

(Additional Financing): Project Administration Manual

Additional Financing for the Southeast Gobi Urban and Border Town Development Project (RRP MON 42184-027) Project Administration Manual Project Number: 42184-027 Loan Number: 3388-MON September 2018 Mongolia: Additional Financing for Southeast Gobi Urban and Border Town Development Project ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ADF – Asian Development Fund DMF – design and monitoring framework EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan IEE – initial environmental examination MCUD – Ministry of Construction and Urban Development MOF – Ministry of Finance NCB – national competitive bidding PAM – project administration manual PMU – project management unit PPMS – project performance management system PUSO – public utility service organization QCBS – quality- and cost-based selection RRP – report and recommendation of the President SGAP – social and gender action plan SOE – statement of expenditure TOR – terms of reference TSA – Treasury single account WSRC – Water Services Regulatory Commission WWTP – wastewater treatment plant CONTENTS Page I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1 A. Rationale 1 B. Impact and Outcome 4 C. Outputs 5 II. IMPLEMENTATION PLANS 6 A. Project Readiness Activities 6 B. Overall Project Implementation Plan 6 III. PROJECT MANAGEMENT ARRANGEMENTS 7 A. Project Implementation Organizations: Roles and Responsibilities 8 B. Key Persons Involved in Implementation 10 C. Project Organization Structure 11 IV. COSTS AND FINANCING 12 A. Cost Estimates 12 B. Key Assumptions 12 C. Revised Project and Financing Plan 13 D. Detailed Cost Estimates by Expenditure Category 15 E. Allocation and Withdrawal of Loan Proceeds 16 F. Detailed Cost Estimates by Financier ($ million) 17 G. Detailed Cost Estimates by Output ($ million) 18 H. Detailed Cost Estimates by Year ($ million) 19 I. Contract and Disbursement S-Curve 20 J.