Sport Climbing and Traditional Climbing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRICAM MANUALE38 R7

TRI-CAM Normal: TRI-CAMS work very well as a fulcrum down. Neither way is best in all to nuts. At first nuts seemed insecure, but "Stingers" with a nut tool or hammer, but other (see Fig. G) situations. Sometimes if you're climbing as familiarity grew their advantages this is using a TRI-CAM as a piton. When normal nut in constricted cracks. (Fig. A). directly above the placement, fulcrum became evident. used in the "tight-fitting" attitude, TRI- C.A.M.P. TRI-CAMS are the result of The tri-pod configuration actually allow Aiding: down will offer the greatest security. At CAMS are very secure and will resist many year’s evolution in cam nut design. s a placement Racking: Sizes 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, Figure A other times (when traversing or angling considerable outward and even upward TRI-CAMS are very fast and efficient on aid. You'll find C.A.M.P. is TRI-CAMS to be the t h a t i n m o s t 2.5, 3, 3.5 and 4 TRI-CAMS may be carried away from the placement) it's best to have force, once you've set them with a good jerk They work exceptionally well in expanding most versatile artificial chock stones cases is more singly or in multiples on carabiners. But the the fulcrum up. But there are no hard and on the sling. flakes and unusual pockets, holes, flares, you’ve ever used. secure than a larger sizes are best carried by clipping the fast rules for this. -

Analysis of the Accident on Air Guitar

Analysis of the accident on Air Guitar The Safety Committee of the Swedish Climbing Association Draft 2004-05-30 Preface The Swedish Climbing Association (SKF) Safety Committee’s overall purpose is to reduce the number of incidents and accidents in connection to climbing and associated activities, as well as to increase and spread the knowledge of related risks. The fatal accident on the route Air Guitar involved four failed pieces of protection and two experienced climbers. Such unusual circumstances ring a warning bell, calling for an especially careful investigation. The Safety Committee asked the American Alpine Club to perform a preliminary investigation, which was financed by a company formerly owned by one of the climbers. Using the report from the preliminary investigation together with additional material, the Safety Committee has analyzed the accident. The details and results of the analysis are published in this report. There is a large amount of relevant material, and it is impossible to include all of it in this report. The Safety Committee has been forced to select what has been judged to be the most relevant material. Additionally, the remoteness of the accident site, and the difficulty of analyzing the equipment have complicated the analysis. The causes of the accident can never be “proven” with certainty. This report is not the final word on the accident, and the conclusions may need to be changed if new information appears. However, we do believe we have been able to gather sufficient evidence in order to attempt an -

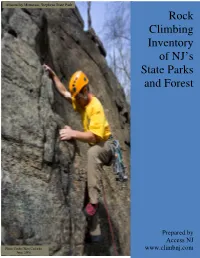

Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ's State Parks and Forest

Allamuchy Mountain, Stephens State Park Rock Climbing Inventory of NJ’s State Parks and Forest Prepared by Access NJ Contents Photo Credit: Matt Carlardo www.climbnj.com June, 2006 CRI 2007 Access NJ Scope of Inventory I. Climbing Overview of New Jersey Introduction NJ’s Climbing Resource II. Rock-Climbing and Cragging: New Jersey Demographics NJ's Climbing Season Climbers and the Environment Tradition of Rock Climbing on the East Coast III. Climbing Resource Inventory C.R.I. Matrix of NJ State Lands Climbing Areas IV. Climbing Management Issues Awareness and Issues Bolts and Fixed Anchors Natural Resource Protection V. Appendix Types of Rock-Climbing (Definitions) Climbing Injury Patterns and Injury Epidemiology Protecting Raptor Sites at Climbing Areas Position Paper 003: Climbers Impact Climbers Warning Statement VI. End-Sheets NJ State Parks Adopt a Crag 2 www.climbnj.com CRI 2007 Access NJ Introduction In a State known for its beaches, meadowlands and malls, rock climbing is a well established year-round, outdoor, all weather recreational activity. Rock Climbing “cragging” (A rock-climbers' term for a cliff or group of cliffs, in any location, which is or may be suitable for climbing) in NJ is limited by access. Climbing access in NJ is constrained by topography, weather, the environment and other variables. Climbing encounters access issues . with private landowners, municipalities, State and Federal Governments, watershed authorities and other landowners and managers of the States natural resources. The motives and impacts of climbers are not distinct from hikers, bikers, nor others who use NJ's open space areas. Climbers like these others, seek urban escape, nature appreciation, wildlife observation, exercise and a variety of other enriching outcomes when we use the resources of the New Jersey’s State Parks and Forests (Steve Matous, Access Fund Director, March 2004). -

Vocabulaire D'escalade Climbing Terms

VOCABULAIRE D'ESCALADE CLIMBING TERMS A - Assurer : To belay Assurer un grimpeur en tête ou en moulinette (To secure a climber) - Assureur : Belayer Personne qui assure un grimpeur (The person securing the climber) - "Avale" / "Sec"/ "Bloque" : "Tight rope" / "Take" Le premier de cordée (ou le second) demande à l'assureur de prendre le mou de la corde (Yelled by the leader or the follower when she/he wants a tighter belay) B - Bac / Baquet : Bucket, Jug Très bonne prise (A large hold) - Baudrier / Baudard : Harness Harnais d'escalade - Bloc : Bouldering, to boulder Escalade de blocs, faire du bloc (Climbing unroped on boulders in Fontainebleau for exemple) C - Casque : Helmet Protection de la tête contre les chutes de pierres... (Protect the head from falling stones...) - Chaussons d'escalade : Climbing shoes Chaussons ou ballerines pourvus d'une gomme très adhérente (Shoes made of sticky rubber) - Corde : Rope - Cotation : Grade Degré de difficulté d'une voie, d'un bloc... (Technical difficulty of the routes, boulders...) - Crux : Crux Le passage délicat dans une voie, le pas de la voie (The hard bit) D - Dalle : Slab Voie ou bloc généralement plat où l'on grimpe en adhérence ou sur grattons (Flat and seemingly featureless, not quite vertical piece of rock) - Daubé / Avoir les bouteilles : Pumped Avoir les avants-bras explosés, ne plus rien sentir... (The felling of overworked muscles) - Dégaine : Quickdraw, quick Deux mousquetons reliés par une sangle (Short sling with karabiners on either side) - Descendeur :Descender Appareil utilisé -

2020 January Scree

the SCREE Mountaineering Club of Alaska January 2020 Volume 63, Number 1 Contents Mount Anno Domini Peak 2330 and Far Out Peak Devils Paw North Taku Tower Randoism via Rosie’s Roost "The greatest danger for Berlin Wall most of us is not that our aim is too high and we Katmai and the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes miss it, but that it is too Peak of the Month: Old Snowy low and we reach it." – Michelangelo JANUARY MEETING: Wednesday, January 8, at 6:30 p.m. Luc Mehl will give the presentation. The Mountaineering Club of Alaska www.mtnclubak.org "To maintain, promote, and perpetuate the association of persons who are interested in promoting, sponsoring, im- proving, stimulating, and contributing to the exercise of skill and safety in the Art and Science of Mountaineering." This issue brought to you by: Editor—Steve Gruhn assisted by Dawn Munroe Hut Needs and Notes Cover Photo If you are headed to one of the MCA huts, please consult the Hut Gabe Hayden high on Devils Paw. Inventory and Needs on the website (http://www.mtnclubak.org/ Photo by Brette Harrington index.cfm/Huts/Hut-Inventory-and-Needs) or Greg Bragiel, MCA Huts Committee Chairman, at either [email protected] or (907) 350-5146 to see what needs to be taken to the huts or repaired. All JANUARY MEETING huts have tools and materials so that anyone can make basic re- Wednesday, January 8, at 6:30 p.m. at the BP Energy Center at pairs. Hutmeisters are needed for each hut: If you have a favorite 1014 Energy Court in Anchorage. -

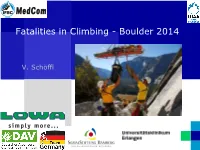

Fatalities in Climbing - Boulder 2014

Fatalities in Climbing - Boulder 2014 V. Schöffl Evaluation of Injury and Fatality Risk in Rock and Ice Climbing: 2 One Move too Many Climbing: Injury Risk Study Type of climbing (geographical location) Injury rate (per 1000h) Injury severity (Bowie, Hunt et al. 1988) Traditional climbing, bouldering; some rock walls 100m high 37.5 a Majority of minor severity using (Yosemite Valley, CA, USA) ISS score <13; 5% ISS 13-75 (Schussmann, Lutz et al. Mountaineering and traditional climbing (Grand Tetons, WY, 0.56 for injuries; 013 for fatalities; 23% of the injuries were fatal 1990) USA) incidence 5.6 injuries/10000 h of (NACA 7) b mountaineering (Schöffl and Winkelmann Indoor climbing walls (Germany) 0.079 3 NACA 2; 1999) 1 NACA 3 (Wright, Royle et al. 2001) Overuse injuries in indoor climbing at World Championship NS NACA 1-2 b (Schöffl and Küpper 2006) Indoor competition climbing, World championships 3.1 16 NACA 1; 1 NACA 2 1 NACA 3 No fatality (Gerdes, Hafner et al. 2006) Rock climbing NS NS 20% no injury; 60% NACA I; 20% >NACA I b (Schöffl, Schöffl et al. 2009) Ice climbing (international) 4.07 for NACA I-III 2.87/1000h NACA I, 1.2/1000h NACA II & III None > NACA III (Nelson and McKenzie 2009) Rock climbing injuries, indoor and outdoor (NS) Measures of participation and frequency of Mostly NACA I-IIb, 11.3% exposure to rock climbing are not hospitalization specified (Backe S 2009) Indoor and outdoor climbing activities 4.2 (overuse syndromes accounting for NS 93% of injuries) Neuhhof / Schöffl (2011) Acute Sport Climbing injuries (Europe) 0.2 Mostly minor severity Schöffl et al. -

Other Chapters Contents

--------- multipitchclimbing.com --------- This site presents the images from the ebook High: Advanced Multipitch Climbing, by David Coley and Andy Kirkpatrick. In order to keep the cost of the book to a minimum most of these were not included in the book. Although they work best when used in conjunction with the book, most are self-explanatory. Please use the following links to buy the book: Amazon USA (kindle) / Amazon UK (kindle) / itunes / kobo Back to Other Chapters Contents 1. Fall Factors / 2. Dynamic Belaying / 3 The 3-5-8 Rule / 4. Belay Device and Rope Choice / 5. Forces Depend on Angles / 6. Failing Daisies / 7. How Fast Do You Climb? / 8. What is a kN? / 9. What is a “Solid” Placement? / 10. A simple mathematical model of a climbing rope / 11. The problem with high energy falls In this chapter we expand on the basic idea of fall factors to account for rope drag, look at testing data from Petzl and Beal on real-word falls, consider if the angles between the arms of a belay really matters that much, look at how your daisy might kill you, introduce a unit of climbing speed (the Steck), discuss what the “kN” on the side of your carabiners means, present one way of defining just what is a solid placement and introduce a simple mathematical model of a rope. 1. Fall Factors The longer the fall the more energy that needs to be absorbed by the rope. The fall factor provides a useful way of distinguishing between falls of equal length (and therefore equal energy) but that have different amounts of rope out to soak up the energy of the fall. -

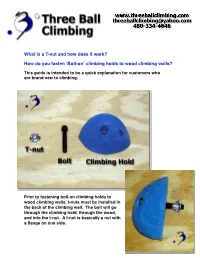

What Is a T-Nut and How Does It Work? How Do You Fasten ʻbolt-Onʼ

What is a T-nut and how does it work? How do you fasten ʻBolt-onʼ climbing holds to wood climbing walls? This guide is intended to be a quick explanation for customers who are brand new to climbing. Prior to fastening bolt-on climbing holds to wood climbing walls, t-nuts must be installed in the back of the climbing wall. The bolt will go through the climbing hold, through the wood, and into the t-nut. A t-nut is basically a nut with a flange on one side. The barrel of the t-nut can fit into a 7/16” hole, but the flange is 1” wide so it cannot fit through the hole. The flange catches the surface of the climbing wall surrounding the 7/16” hole. The Barrel of the T-nut should be recessed behind the front surface of the climbing wall by at least 1/ 4”. Climbing holds must not make di- rect contact with the t-nut. If the climbing hold makes direct con- tact with the t-nut it will eliminate the friction between the surface of the climbing wall and the back of the climbing hold. Climbing holds must have good contact with the climbing wall in order to be secure. Selecting the proper length bolts: Every climbing hold has a different shape and structure. Because of these variations, the depth of the bolt hole varies from one climbing hold to another. Frogs 20 Pack Example: The 20 pack of Frogs Jugs to the right consists of several different shaped grips. -

OUTDOOR ROCK CLIMBING INTENSIVE INTRODUCTION Boulder, CO EQUIPMENT CHECKLIST

www.alpineinstitute.com [email protected] Equipment Shop: 360-671-1570 Administrative Office: 360-671-1505 The Spirit of Alpinism OUTDOOR ROCK CLIMBING INTENSIVE INTRODUCTION Boulder, CO EQUIPMENT CHECKLIST This equipment list is aimed to help you bring only the essential gear for your mountain adventures. Please read this list thoroughly, but exercise common sense when packing for your trip. Climbs in the summer simply do not require as much clothing as those done in the fall or spring. Please pack accordingly and ask questions if you are uncertain. CLIMATE: Temperatures and weather conditions in Boulder area are often conducive to great climbing conditions. Thunderstorms, however, are somewhat common and intense rainstorms often last a few hours in the afternoons. Daytime highs range anywhere from 50°F to 80°F. GEAR PREPARATION: Please take the time to carefully prepare and understand your equipment. If possible, it is best to use it in the field beforehand. Take the time to properly label and identify all personal gear items. Many items that climbers bring are almost identical. Your name on a garment tag or a piece of colored electrical tape is an easy way to label your gear; fingernail polish on hard goods is excellent. If using tape or colored markers, make sure your labeling method is durable and water resistant. ASSISTANCE: At AAI we take equipment and its selection seriously. Our Equipment Services department is expertly staffed by climbers, skiers and guides. Additionally, we only carry products in our store have been thoroughly field tested and approved by our guides. This intensive process ensures that all equipment that you purchase from AAI is best suited to your course and future mountain adventures. -

White Mountain National Forest Pemigewasset Ranger District November 2015

RUMNEY ROCKS CLIMBING MANAGEMENT PLAN White Mountain National Forest Pemigewasset Ranger District November 2015 Introduction The Rumney Rocks Climbing Area encompasses approximately 150 acres on the south-facing slopes of Rattlesnake Mountain on the White Mountain National Forest (WMNF) in Rumney, New Hampshire. Scattered across these slopes are approximately 28 rock faces known by the climbing community as "crags." Rumney Rocks is a nationally renowned sport climbing area with a long and rich climbing history dating back to the 1960s. This unique area provides climbing opportunities for those new to the sport as well as for some of the best sport climbers in the country. The consistent and substantial involvement of the climbing community in protection and management of this area is a testament to the value and importance of Rumney Rocks. This area has seen a dramatic increase in use in the last twenty years; there were 48 published climbing routes at Rumney Rocks in Ed Webster's 1987 guidebook Rock Climbs in the White Mountains of New Hampshire and are over 480 documented routes today. In 2014 an estimated 646 routes, 230 boulder problems and numerous ice routes have been documented at Rumney. The White Mountain National Forest Management Plan states that when climbing issues are "no longer effectively addressed" by application of Forest Plan standards and guidelines, "site specific climbing management plans should be developed." To address the issues and concerns regarding increased use in this area, the Forest Service developed the Rumney Rocks Climbing Management Plan (CMP) in 2008. Not only was this the first CMP on the White Mountain National Forest, it was the first standalone CMP for the US Forest Service. -

Kitsap Basic Climbing

! KITSAP MOUNTAINEERS BASIC CLIMBING COURSE Class 4 and Field Trips 4 & 5 BASIC CLIMBING - CLASS #4 ROCK CLIMBING Class #4 Topics Rock Climbing Process Rock Climbing Techniques Anchors Field Trip Leader Q & A (Field Trip 4) Assigned Reading (complete prior to Class #4) Assigned Reading: Freedom Of The Hills Subject Alpine Rock Climbing ...............................................................Ch 12 Basic Climbing Course Manual All Class #4 Material Additional Resources Find a good book on stretching exercises—it is helpful to loosen up before rock climbing. ROPED CLIMBING OVERVIEW Roped climbing involves the leader and follower(s) attached to a rope for protection as they ascend and descend, so that in the event of a fall the rope can be used to catch the falling climber. In basic rock climbing, the leader is tied into one end of a rope and the follower (second) into the other end. The follower may also attach to a “ground anchor” and will prepare to belay the leader by feeding the rope through his/her belay device. When the follower (belayer) is ready (follower yells: “BELAY ON”), the leader ascends a section of rock (leader: “CLIMBING”, follower: “CLIMB”) while placing protection gear and connecting the climbing rope to the protection as he/she climbs upward. In event of a fall (leader: “FALLING!”), the belayer stops the fall by “braking” the rope at the belay device, and tightening the rope through the protections. When the leader has reached the top of the section (pitch), the leader sets up an anchor and attaches him/ her. The leader tells the follower to take him/her off belay (leader: “OFF BELAY”). -

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue.