Selected and Adapted by Rabbi Dov Karoll Quote from the Rosh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

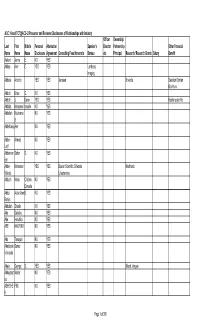

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon Ha-Ra and Motzi Shem Ra and Disclosing Another’S Confidential Secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon ha-ra and motzi shem ra and disclosing another’s confidential secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech Deut. 24:9 - "Remember what the L-rd your G-d did unto Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt." Specifically, she spoke against her brother Moses. Yerushalmi Berachos 1:2 Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai said, “Had I been at Mount Sinai at the moment when the torah was given to Yisrael I would have demanded that man should have been created with two mouths- one for Torah and prayer and other for mundane matters. But then I retracted and exclaimed that if we fail and speak lashon hara with only one mouth, how much more so would we fail with two mouths Bavli Arakhin15b R. Yochanan said in the name of R.Yosi ben Zimra: He who speaks slander, is as though he denied the existence of the Lord: With out tongue will we prevail our lips are our own; who is lord over us? (Ps.12:5) Gen R. 65:1 and Lev.R. 13:5 The company of those who speak slander cannot greet the Presence Sotah 5a R. Hisda said in the name of Mar Ukba: When a man speaks slander, the holy one says, “I and he cannot live together in the world.” So scripture: “He who slanders his neighbor in secret…. Him I cannot endure” (Ps. 101:5).Read not OTO “him’ but ITTO “with him [I cannot live] Deut.Rabbah 5:10 R.Mana said: He who speaks slander causes the Presence to depart from the earth below to heaven above: you may see foryourselfthat this is so.Consider what David said: “My soul is among lions; I do lie down among them that are aflame; even the sons of men, whose teeth are spears and arrows, and their tongue a sharp sword” (Ps.57:5).What follows directly ? Be Thou exalted O God above the heavens (Ps.57:6) .For David said: Master of the Universe what can the presence do on the earth below? Remove the Presence from the firmament. -

Miriyam Goldman OA Thesis 9Dec20.Pdf (247.7Kb)

The Living Stone: The Talmudic Paradox of the Seventh Month Gestational Viability vs. the Eighth Month Non-Viability Presented to the S. Daniel Abraham Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Completion of the Program Stern College for Women Yeshiva University December 9, 2020 Miriyam A. Goldman Mentor: Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss, Biology Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 4 Background to Pregnancy ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Talmudic Sources on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………. 6 Meforshim on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………………. 9 Secular Sources of the Dilemma ………………………………………………………………. 11 The Significance of Hair and Nails in Terms of Viability……………………………….……... 14 The Definition of Nefel’s Impact on Viability ……………………………………………….. 17 History of Premature Survival ………………………………………………………………… 18 Statistics on Prematurity ………………………………………………………………………. 19 Developmental Differences Between Seventh and Eighth Months ……………………….…. 20 Contemporary Talmudic Balance of the Dilemma..…………………………………….…….. 22 Contemporary Secular Balance of the Dilemma .……………………………………….…….. 24 Evaluation of Talmudic Accreditation …………………………………………………..…...... 25 Interviews with Rabbi Eitan Mayer, Rabbi Daniel Stein, and Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss .…...... 27 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 29 References…..………………………………………………………………………………..… 34 2 Abstract This paper reviews the viability of premature infants, specifically the halachic status of those born in -

Shavuot 5780 Divrei Torah

Shavuot 5780 Divrei Torah Sponsored by: Debbie and Orin Golubtchik in honor of: The yahrzeits of Orin's parents חביבה בת שמואל משה בן חיים ליב Barbara and Simcha Hochman & family in memory of: • Simcha’s father, Rabbi Jonas Hochman a"h and • Gedalya ben Avraham, Blima bat Yaakov, Eeta bat Noach and Chaya bat Gedalya, who were murdered upon arrival at Birkenau on the 2nd day Shavuot. Table of Contents Page 3 Forward by Rabbi Adler ”That which you can and cannot do on Yom Tov אכל נפש“ Page 5 Yaakov Blau “Shifting voices in the narrative of Tanach” Page 9 Leeber Cohen “The Importance of Teaching Torah to Grandchildren” Page 11 Elchanan Dulitz “Bezchus Rabbi Dr. Baruch Tzvi ben R. Reuven Nassan z”l Mai Chanukah” Page 15 Martin Fineberg “Shavuos 5780 D’var Torah” Page 19 Yehuda Halpert “Ruth and Orpah’s Wedding Album: Fake News or Biblical Commentary” Page 23 Terry Novetsky “The “Mitzva” of Shavuot” Page 31 Yitzchak Shulman “Parshat Behaalotcha “ Page 33 Bernard Stahl The Meaning of Humility Page 41 Murray Sragow “Jews and Booze—A look at Jewish responses to Prohibition” Page 49 Mark Teicher “Intertextuality/Numerology” Page 50 Mark Zitter ”קרבנות של חג השבועות“ 2 Forward by Rabbi Adler Chaveireinu HaYikarim, Every year on the first night of Shavuot many of us get together for the purpose of learning with one another. There are multiple shiurim and many hours of chavruta learning . Unfortunately, in today’s climate we cannot learn with one another but we can learn from one another. Enclosed are a variety of Torah articles on many different topics which you are invited to enjoy during the course of Zman Matan Torahteinu. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Shabbos Secrets - the Mysteries Revealed

Translated by Rabbi Awaharn Yaakov Finkel Shabbos Secrets - The Mysteries Revealed First Published 2003 Copyright O 2003 by Rabbi Dovid D. Meisels ISBN: 1-931681-43-0 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in an form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording, or otherwise, withour prior permission in writing from both the copyright holder and publisher. C<p.?< , . P*. P,' . , 8% . 3: ,. ""' * - ;., Distributed by: Isreal Book Shop -WaUvtpttrnn 501 Prospect Street w"Jw--.or@r"wn owwv Lakewood NJ 08701 Tel: (732) 901-3009 Fax: (732) 901-4012 Email: isrbkshp @ aol.com Printed in the United States of America by: Gross Brothers Printing Co., Inc. 3 125 Summit Ave., Union City N.J. 07087 This book is dedicated to be a source of merit in restoring the health and in strengthening 71 Tsn 5s 3.17 ~~w7 May Hashem send him from heaven a speedy and complete recovery of spirit and body among the other sick people of Israel. "May the Zechus of Shabbos obviate the need to cry out and may the recovery come immediately. " His parents should inerit to have much nachas from him and from the entire family. I wish to express my gratitude to Reb Avraham Yaakov Finkel, the well-known author and translator of numerous books on Torah themes, for his highly professional and meticulous translation from the Yiddish into lucid, conversational English. The original Yiddish text was published under the title Otzar Hashabbos. My special appreciation to Mrs. -

Mishnays Chayim Merged.Indd

MISHNAS CHAYIM A project of CHEVRAH LOMDEI MISHNAH ❧ Parshas Tzav 5768 Officially, Purim may have ended, but the festive At first glance, the juxtaposition of these two air of the Yom Tov has by no means dissipated. As passages may seem somewhat strange. Rava tells the effects (hangover or otherwise) of the holiday us a halachah, followed by the Gemara’s continue to be felt, it is appropriate to contemplate immediate description of an event where the various aspects of the Purim experience. someone’s fulfillment of this mitzvah had disastrous consequences. A case in point is this most perplexing mitzvah of ad d’lo yada—drinking on Purim. Throughout the Indeed, the Rabbeinu Efraim (quoted by the Ran) ages, the Chachamim have expressed wonderment feels that the intent of the Gemara is clearly a concerning this directive; how could Chazal have rejection of Rava’s din. By recounting this death- obligated us to partake in an activity which could defying episode on the heels of Rava’s teaching, potentially lead to raucous or even harmful the Gemara demonstrates exactly what such a behavior? In fact, as we shall see, some authorities practice can lead to. are of the opinion that no such obligation exists. The revelers, however, need not be totally The source for the halachah obligating drinking is discouraged, as other Rishonim disagree with the Gemara in Megillah (7b): Rabbeinu Efraim’s understanding of the issue. The .Tur and the Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim sec אמר רבא מיחייב איניש לבסומי בפוריא עד דלא ;both quote Rava’s halachah verbatim (695 ידע בי ארור המ לברו מרדכי. -

OF 17Th 2004 Gender Relationships in Marriage and Out.Pdf (1.542Mb)

Gender Relationships In Marriage and Out Edited by Rivkah Blau Robert S. Hirt, Series Editor THE MICHAEL SCHARF PUBLICATION TRUST of the YESHIVA UNIVERSITY PRESs New York OF 17 r18 CS2ME draft 8 balancediii iii 9/2/2007 11:28:13 AM THE ORTHODOX FORUM The Orthodox Forum, initially convened by Dr. Norman Lamm, Chancellor of Yeshiva University, meets each year to consider major issues of concern to the Jewish community. Forum participants from throughout the world, including academicians in both Jewish and secular fields, rabbis,rashei yeshivah, Jewish educators, and Jewish communal professionals, gather in conference as a think tank to discuss and critique each other’s original papers, examining different aspects of a central theme. The purpose of the Forum is to create and disseminate a new and vibrant Torah literature addressing the critical issues facing Jewry today. The Orthodox Forum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Joseph J. and Bertha K. Green Memorial Fund at the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary established by Morris L. Green, of blessed memory. The Orthodox Forum Series is a project of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, an affiliate of Yeshiva University OF 17 r18 CS2ME draft 8 balancedii ii 9/2/2007 11:28:13 AM Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Orthodox Forum (17th : 2004 : New York, NY) Gender relationships in marriage and out / edited by Rivkah Blau. p. cm. – (Orthodox Forum series) ISBN 978-0-88125-971-1 1. Marriage. 2. Marriage – Religious aspects – Judaism. 3. Marriage (Jewish law) 4. Man-woman relationships – Religious aspects – Judaism. I. -

Derech Hateva 2018.Pub

Derech HaTeva A Journal of Torah and Science A Publication of Yeshiva University, Stern College for Women Volume 22 2017-2018 Co-Editors Elana Apfelbaum | Tehilla Berger | Hannah Piskun Cover & Layout Design Shmuel Ormianer Printing Advanced Copy Center, Brooklyn, NY 11230 Acknowledgements The editors of this year’s volume would like to thank Dr. Harvey Babich for the incessant time and effort that he devotes to this journal. Dr. Babich infuses his students with a passion for the Torah Umadda vision and serves as an exemplar of this philosophy to them. Through his constant encouragement and support, students feel confident to challenge themselves and find interesting connections between science and Torah. Dr. Babich, thank you for all the effort you contin- uously devote to us through this journal, as well as to our personal and future lives as professionals and members of the Jewish community. The publication of Volume 22 of this journal was made possible thanks to the generosity of the following donors: Dr. and Mrs. Harvey Babich Mr. and Mrs. Louis Goldberg Dr. Fred and Dr. Sheri (Rosenfeld) Grunseid Rabbi and Mrs. Baruch Solnica Rabbi Joel and Dr. Miriam Grossman Torah Activities Council YU Undergraduate Admissions We thank you for making this opportunity possible. Elana Apfelbaum Tehilla Berger Hannah Piskun Dedication We would like to dedicate the 22nd volume of Derech HaTeva: A Journal of Torah and Science to the soldiers of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). Formed from the ashes of the Holocaust, the Israeli army represents the enduring strength and bravery of the Jewish people. The soldiers of the IDF have risked their lives to protect the Jewish nation from adversaries in every generation in wars such as the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War. -

Daf Ditty Yoma 4: Access to the Divine, the Paradox

Daf Ditty Yoma 4: Access to the Divine, the Paradox Life … is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. William Shakespeare, Macbeth 1 2 3 4 § And a baraita was taught in accordance with the opinion of Reish Lakish that sequestering is derived from Sinai: Moses ascended in the cloud, and was covered in the cloud, and was sanctified in the cloud, in order to receive the Torah for the Jewish people in sanctity, as it is stated: “And the glory of the Lord abode upon Mount Sinai and the cloud covered him six days, and He called to Moses on the seventh day from the midst of the cloud” (Exodus 24:16). This was an incident that occurred after the revelation of the Ten Commandments to the Jewish people, and these six days were the beginning of the forty days that Moses was on the mountain (see Exodus 24:18); this is the statement of Rabbi Yosei HaGelili. The opinion of Rabbi Yosei HaGelili corresponds to that of Reish Lakish; Moses withdrew for six days before receiving permission to stand in the presence of God. 5 Rabbi Akiva says: This incident occurred before the revelation of the Ten Commandments to the Jewish people, and when the Torah says: “And the glory of the Lord abode upon Mount Sinai,” it is referring to the revelation of the Divine Presence that began on the New Moon of Sivan, which was six days before the revelation of the Ten Commandments. And that which is written: “And the cloud covered him,” means the cloud covered it, the mountain, and not him, Moses.