Jews, by Choice Conversion and the Formation of Jewish Identity by Jeffrey Spitzer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Jews Quote

Oral Tradition, 29/1 (2014):5-46 Why Jews Quote Michael Marmur Everyone Quotes1 Interest in the phenomenon of quotation as a feature of culture has never been greater. Recent works by Regier (2010), Morson (2011) and Finnegan (2011) offer many important insights into a practice notable both for its ubiquity and yet for its specificity. In this essay I want to consider one of the oldest and most diverse of world cultures from the perspective of quotation. While debates abound as to whether the “cultures of the Jews”2 can be regarded integrally, this essay will suggest that the act of quotation both in literary and oral settings is a constant in Jewish cultural creativity throughout the ages. By attempting to delineate some of the key functions of quotation in these various Jewish contexts, some contribution to the understanding of what is arguably a “universal human propensity” (Finnegan 2011:11) may be made. “All minds quote. Old and new make the warp and woof of every moment. There is not a thread that is not a twist of these two strands. By necessity, by proclivity, and by delight, we all quote.”3 Emerson’s reference to warp and woof is no accident. The creative act comprises a threading of that which is unique to the particular moment with strands taken from tradition.4 In 1 The comments of Sarah Bernstein, David Ellenson, Warren Zev Harvey, Jason Kalman, David Levine, Dow Marmur, Dalia Marx, Michal Muszkat-Barkan, and Richard Sarason on earlier versions of this article have been of enormous help. -

Creation and Composition

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Martin Hengel und Peter Schäfer 114 ARTIBUS ,5*2 Creation and Composition The Contribution of the Bavli Redactors (Stammaim) to the Aggada Edited by Jeffrey L. Rubenstein Mohr Siebeck Jeffrey L. Rubenstein, born 1964. 1985 B.A. at Oberlin College (OH); 1987 M.A. at The Jewish Theological Seminary of America (NY); 1992 Ph.D. at Columbia University (NY). Professor in the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, New York University. ISBN 3-16-148692-7 ISSN 0721-8753 (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism) Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2005 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to repro- ductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen, printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Preface The papers collected in this volume were presented at a conference sponsored by the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies of New York University, February 9-10, 2003.1 am grateful to Lawrence Schiffman, chairman of the de- partment, for his support, and to Shayne Figueroa and Diane Leon-Ferdico, the departmental administrators, for all their efforts in logistics and organization. -

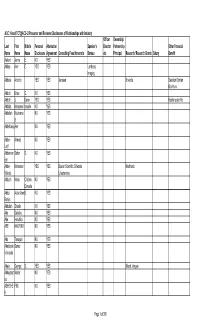

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept of Kingship

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Jacob Douglas Feeley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Jacob Douglas, "Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2276. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Abstract Scholars who have discussed Josephus’ political philosophy have largely focused on his concepts of aristokratia or theokratia. In general, they have ignored his concept of kingship. Those that have commented on it tend to dismiss Josephus as anti-monarchical and ascribe this to the biblical anti- monarchical tradition. To date, Josephus’ concept of kingship has not been treated as a significant component of his political philosophy. Through a close reading of Josephus’ longest text, the Jewish Antiquities, a historical work that provides extensive accounts of kings and kingship, I show that Josephus had a fully developed theory of monarchical government that drew on biblical and Greco- Roman models of kingship. Josephus held that ideal kingship was the responsible use of the personal power of one individual to advance the interests of the governed and maintain his and his subjects’ loyalty to Yahweh. The king relied primarily on a standard array of classical virtues to preserve social order in the kingdom, protect it from external threats, maintain his subjects’ quality of life, and provide them with a model for proper moral conduct. -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon Ha-Ra and Motzi Shem Ra and Disclosing Another’S Confidential Secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon ha-ra and motzi shem ra and disclosing another’s confidential secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech Deut. 24:9 - "Remember what the L-rd your G-d did unto Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt." Specifically, she spoke against her brother Moses. Yerushalmi Berachos 1:2 Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai said, “Had I been at Mount Sinai at the moment when the torah was given to Yisrael I would have demanded that man should have been created with two mouths- one for Torah and prayer and other for mundane matters. But then I retracted and exclaimed that if we fail and speak lashon hara with only one mouth, how much more so would we fail with two mouths Bavli Arakhin15b R. Yochanan said in the name of R.Yosi ben Zimra: He who speaks slander, is as though he denied the existence of the Lord: With out tongue will we prevail our lips are our own; who is lord over us? (Ps.12:5) Gen R. 65:1 and Lev.R. 13:5 The company of those who speak slander cannot greet the Presence Sotah 5a R. Hisda said in the name of Mar Ukba: When a man speaks slander, the holy one says, “I and he cannot live together in the world.” So scripture: “He who slanders his neighbor in secret…. Him I cannot endure” (Ps. 101:5).Read not OTO “him’ but ITTO “with him [I cannot live] Deut.Rabbah 5:10 R.Mana said: He who speaks slander causes the Presence to depart from the earth below to heaven above: you may see foryourselfthat this is so.Consider what David said: “My soul is among lions; I do lie down among them that are aflame; even the sons of men, whose teeth are spears and arrows, and their tongue a sharp sword” (Ps.57:5).What follows directly ? Be Thou exalted O God above the heavens (Ps.57:6) .For David said: Master of the Universe what can the presence do on the earth below? Remove the Presence from the firmament. -

Martin Shichtman Named Director of EMU Jewish Studies

Washtenaw Jewish News Presort Standard In this issue… c/o Jewish Federation of Greater Ann Arbor U.S. Postage PAID 2939 Birch Hollow Drive Ann Arbor, MI Federation Biking 2010 Ann Arbor, MI 48108 Permit No. 85 Main Event Adventure Election In Israel Results Page 5 Page 7 Page 20 December 2010/January 2011 Kislev/Tevet/Shevat 5771 Volume XXXV: Number 4 FREE Martin Shichtman named director of EMU Jewish Studies Chanukah Wonderland at Geoff Larcom, special to the WJN Briarwood Mall Devorah Goldstein, special to the WJN artin Shichtman, a professor of Shichtman earned his doctorate and mas- English language and literature ter’s degree from the University of Iowa, and What is white, green, blue and eight feet tall? M who has taught at Eastern Michi- his bachelor’s degree from the State Univer- —the menorah to be built at Chanukah Won- gan University for 26 years, has been appointed sity of New York, Binghamton. He has taught derland this year. Chabad of Ann Arbor will director of Jewish Studies for the university. more than a dozen courses at the graduate sponsor its fourth annual Chanukah Wonder- As director, Shichtman will create alliances and undergraduate levels at EMU, including land, returning to the Sears wing of Briarwood with EMU’s Jewish community, coordinate classes on Chaucer, Arthurian literature, and Mall, November 29–December 6, noon–7 p.m. EMU’s Jewish Studies Lecture Series and de- Jewish American literature. Classes focusing New for Chanukkah 2010 will be the building of velop curriculum. The area of Jewish studies on Jewish life include “Imagining the Holy a giant Lego menorah in the children’s play area includes classes for all EMU students inter- Land,” and “Culture and the Holocaust.” (near JCPenny). -

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

The Jewish Jesus

The Jewish Jesus Revelation, Reflection, Reclamation http://www.servantofmessiah.org Shofar Supplements in Jewish Studies Editor Zev Garber Los Angeles Valley College Case Western Reserve University Managing Editor Nancy Lein Purdue University Editorial Board Dean Bell Spertus Institute of Jewish Studies Louis H. Feldman Yeshiva University Saul S. Friedman Youngstown State University Joseph Haberer Purdue University Peter Haas Case Western Reserve University Rivka Ulmer Bucknell University Richard L. Libowitz Temple University and St. Joseph’s University Rafael Medoff The David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies Daniel Morris Purdue University Marvin A. Sweeney Claremont School of Theology and Claremont Graduate University Ziony Zevit American Jewish University Bruce Zuckerman University of Southern California http://www.servantofmessiah.org The Jewish Jesus Revelation, Reflection, Reclamation Edited by Zev Garber Purdue University Press / West Lafayette, Indiana http://www.servantofmessiah.org Copyright 2011 by Purdue University. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Jewish Jesus : revelation, reflection, reclamation / edited by Zev Garber. p. cm. -- (Shofar supplements in Jewish studies) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-55753-579-5 1. Jesus Christ--Jewish interpretations. 2. Judaism--Relations--Christianity. 3. Christianity and other religions--Judaism. I. Garber, Zev, 1941- BM620.J49 2011 232.9'06--dc22 2010050989 Cover image: James Tissot, French, 1836-1902. Jesus Unrolls the Book in the Synagogue (Jésus dans la synagogue déroule le livre). 1886-1894. Opaque watercolor over graphite on gray wove paper. Image: 10 11/16 x 7 9/16 in. (27.1 x 19.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum. -

Fathers of the World. Essay in Rabbinic and Patristic Literatures

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Otfried Hofius 80 Fathers of the World Essays in Rabbinic and Patristric Literatures by Burton L. Visotzky J. C. B. Möhr (Paul Siebeck) Tübingen Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Visotzky, Burton L.: Fathers of the world: essays in rabbinic and patristic literatures / by Burton L. Visotzky. - Tübingen: Mohr, 1995 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament; 80) ISBN 3-16-146338-2 NE: GT © 1995 by J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O. Box 2040, D-72010 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by ScreenArt in Wannweil using Times typeface, printed by Guide- Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper from Papierfabrik Buhl in Ettlingen and bound by Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. Printed in Germany. ISSN 0512-1604 Acknowledgements It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many scholars and institutions that have assisted me in writing this book. The essays in this volume were written during the last decade. For all those years and more I have had the privilege of being on the faculty of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. It is truly the residence of a host of disciples of the sages who love the Torah. Daily I give thanks to God that I am among those who dwell at the Seminary. One could not ask for better teachers, colleagues or students. -

Talmudic Metrology IV: Halakhic Currency

Talmudic Metrology IV: The Halakhic Currency Abstract. In 66 B.C.E. Palestine entered under Roman protection and from 6 C.E. on it would be under Roman administration. This situation persisted until the conquest by the Persians in the beginning of the seventh century. The Jerusalem Talmud was thus completely elaborated under Roman rule. Therefore, as for the other units of measure, the Halakhik coinage and the Jerusalem Talmudic monetary denominations are completely dependent on Roman coinage of the time and Roman economic history. Indeed, during the first century Tyrian coinage was similar to the imperial Roman coinage. Nevertheless, during the third century the debasement of Roman money became significant and the Rabbis had difficulty finding the Roman equivalents of the shekel, in which the Torah obligations are expressed and of the prutah, the least amount in Jewish law. In this article we describe the Halakhik coinage, originally based on the Tyrian coinage, and examine the history of the Shekel and the Prutah. We then examine the exegesis of different Talmudic passages related to monetary problems and to the Halakhic coinage, which cannot be correctly understood without referring to Roman economic history and to numismatic data that was unknown to the traditional commentators of the Talmud. Differences between parallel passages of both the Jerusalem and the Babylonian Talmud can then be explained by referring to the economical situation prevailing in Palestine and Babylonia. For example, the notion of Kessef Medina, worth one eighth of the silver denomination, is a Babylonian reality that was unknown to Palestinian Tanaïm and Amoraïm.