Are Special Needs Qualifications and Teaching Experience Factors in Teacher Attitudes Towards Collaborative Action Plans?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

„Lochbusch-Königswiesen“

Berichte aus den Arbeitskreisen wert und erfordert diese eigentlich auch. Doch es zeichnet sich nicht ab, dass eine sol- che Untersuchung in absehbarer Zeit zustande kommen könnte. Und ehe die Vergangenheit und der gegenwärtige Zustand der „Mitteltrumm“ womöglich in Vergessenheit geraten, erscheint es doch vernünftiger, die Befunde trotz ihrer Män- gel und Lücken hier vorzulegen. Die Vege- tationsaufnahmen wurden in der ersten Junihälfte 2010 erhoben (Größe jeweils ca. 25 m²). Entwicklung der Flur „Mitteltrumm“ zwischen 1978 und den frühen 1990er Jahren Im Jahr 1978 beabsichtigte der Golfclub „Pfalz“ die Erweiterung seines Platzes auf der Flur „Mitteltrumm“. Dazu wurde der Oberboden abgeschält und am Nordrand der Fläche auf einer Halde gelagert. Zurück Abb. 3: Epipactis helleborine subsp. xzirnsackiana, Einzelblüte, 2.8.2008, Weißelstein NW blieb eine vegetationsfreie „Mondland- Glanbrücken (Pfalz). schaft“. Der Golfclub hatte jedoch keine Genehmi- gung für die Maßnahmen. Sie wurden daher HEINTZ, I. 2001: Limodorum abortivum, der Von der „Mondlandschaft“ durch die Landespflegebehörde gestoppt – Dingel, ein Neufund in der Pfalz. – POLLI- zur Pfeifengraswiese: seit dem Februar 1976 lag bei der damaligen CHIA-Kurier 17(3): 13, Bad Dürkheim. Die Flur „Mitteltrumm“ im Bezirksregierung ein Antrag auf Auswei- HERR-HEIDTKE, D. & HEIDTKE, U.H.J. 2010: Die Naturschutzgebiet sung eines Naturschutzgebiets vor, das die Orchideengattung Ophrys (Ragwurz) und „Lochbusch-Königswiesen“ Flur „Mitteltrumm“ einschließen sollte. In ihre Hybriden im NSG Badstube bei Zweibrü- welchem Zustand sich die „Mitteltrumm“ cken. – POLLICHIA-Kurier 26(4): 10- damals, vor dem Eingriff durch den Golf- 11+53,54, Bad Dürkheim. Zu den floristisch bedeutendsten Feucht- club, befunden hatte, lässt sich nicht mehr PETEREK, M. -

The Present Status of the River Rhine with Special Emphasis on Fisheries Development

121 THE PRESENT STATUS OF THE RIVER RHINE WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT T. Brenner 1 A.D. Buijse2 M. Lauff3 J.F. Luquet4 E. Staub5 1 Ministry of Environment and Forestry Rheinland-Pfalz, P.O. Box 3160, D-55021 Mainz, Germany 2 Institute for Inland Water Management and Waste Water Treatment RIZA, P.O. Box 17, NL 8200 AA Lelystad, The Netherlands 3 Administrations des Eaux et Forets, Boite Postale 2513, L 1025 Luxembourg 4 Conseil Supérieur de la Peche, 23, Rue des Garennes, F 57155 Marly, France 5 Swiss Agency for the Environment, Forests and Landscape, CH 3003 Bern, Switzerland ABSTRACT The Rhine basin (1 320 km, 225 000 km2) is shared by nine countries (Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, France, Luxemburg, Belgium and the Netherlands) with a population of about 54 million people and provides drinking water to 20 million of them. The Rhine is navigable from the North Sea up to Basel in Switzerland Key words: Rhine, restoration, aquatic biodiversity, fish and is one of the most important international migration waterways in the world. 122 The present status of the river Rhine Floodplains were reclaimed as early as the and groundwater protection. Possibilities for the Middle Ages and in the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- restoration of the River Rhine are limited by the multi- tury the channel of the Rhine had been subjected to purpose use of the river for shipping, hydropower, drastic changes to improve navigation as well as the drinking water and agriculture. Further recovery is discharge of water, ice and sediment. From 1945 until hampered by the numerous hydropower stations that the early 1970s water pollution due to domestic and interfere with downstream fish migration, the poor industrial wastewater increased dramatically. -

Bestandsdichte Der Wasseramsel (Cinclus Cinclus) an Der Wiese (Südschwarzwald)

Bestandsdichte der Wasseramsel (Cinclus cinclus) an der Wiese (Südschwarzwald) Erhard Gabler und Karl Kuhn Summary: GABLER, E., & K. KUHN (2003): Population density of the Dipper (Cinclus cinclus) at the river ‘Wiese’ (Southern Black Forest). – Naturschutz südl. Oberrhein 4: 21-28. On a total length of 54 km of the river ‘Wiese’ the average population density of the Dipper reaches a high value with 2 individuals/km. Great differences exist between the upper ‘Wiese’ in the Black Forest with an average of 3 individuals/km and a maximum of 5 to 6 individuals/km and the lower ‘Wiese’ with 1 indi- vidual/km. This is attributed to different habitat conditions. Keywords: Cinclus cinclus, abundance, breeding habitat, river ‘Wiese’, Southern Black Forest. 1. Einleitung teten Wasseramseln in drei Gruppen aufgeteilt: • Einzelne Vögel. Dabei kann es sich sowohl um Die Wiese* ist die zentrale Leitlinie des Südschwarz- unverpaarte Vögel handeln als auch um solche, waldes. Mit einer Länge von 54 km ist sie mit Aus- deren Partner auf dem Nest sitzt oder sich ver- nahme des kurzen, tobelartigen Quellbaches von ih- steckt hält. rem Oberlauf bis zu ihrer Mündung von der Wasser- • Paare mit Revierverhalten, von denen aber ein amsel besiedelt. Es lag nahe, eine Bestandsaufnahme Brutnachweis fehlt. entlang dieser Leitlinie durchzuführen, da bisher nur • Brutpaare. Zu dieser Gruppe zählen wir alle unzureichende Einzeldaten (SCHNEIDER 1985) vorla- Vögel, die wir beim Nestbau, an oder im Nest, mit gen. Da die Wiese auf ihrem Lauf mehrfach ihren Futter im Schnabel oder zusammen mit einem Charakter ändert, lassen sich nicht nur Aussagen Jungvogel beobachtet haben. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2019 8:45:44 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Ramil Abbasov Chariman of the Managing Spektr Socio-Economic Azerbaijan Board Researches and Development Public Union Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Educaiton for Employment - United States EFE HAGAR ABDELRAHM African affairs & SDGs Unit Maat for Peace, Development Egypt AN Manager and Human Rights Abukar Abdi CEO Juba Foundation Kenya Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Mala Abdulaziz Executive director Swift Relief Foundation Nigeria Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Yussuf Abdullahi Regional Team Lead Pact Kenya Abdulahi Abdulraheem Executive Director Initiative for Sound Education Nigeria Relationship & Health Muttaqa Abdulra'uf Research Fellow International Trade Union Nigeria Confederation (ITUC) Kehinde Abdulsalam Interfaith Minister Strength in Diversity Nigeria Development Centre, Nigeria Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Shahlo Abdunabizoda Director Jahon Tajikistan Shontaye Abegaz Executive Director International Insitute for Human United States Security Subhashini Abeysinghe Research Director Verite -

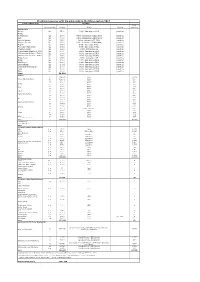

Stocking Measures with Big Salmonids in the Rhine System 2017

Stocking measures with big salmonids in the Rhine system 2017 Country/Water body Stocking smolt Kind and stage Number Origin Marking equivalent Switzerland Wiese Lp 3500 Petite Camargue B1K3 genetics Rhine Riehenteich Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue K1K2K4K4a genetics Birs Lp 4.000 Petite Camargue K1K2K4K4a genetics Arisdörferbach Lp 1.500 Petite Camargue F1 Wild genetics Hintere Frenke Lp 2.500 Petite Camargue K1K2K4K4a genetics Ergolz Lp 3.500 Petite Camargue K7C1 genetics Fluebach Harbotswil Lp 1.300 Petite Camargue K7C1 genetics Magdenerbach Lp 3.900 Petite Camargue K5 genetics Möhlinbach (Bachtele, Möhlin) Lp 600 Petite Camargue B7B8 genetics Möhlinbach (Möhlin / Zeiningen) Lp 2.000 Petite Camargue B7B8 genetics Möhlinbach (Zuzgen, Hellikon) Lp 3.500 Petite Camargue B7B8 genetics Etzgerbach Lp 4.500 Petite Camargue K5 genetics Rhine Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Old Rhine Lp 2.500 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Bachtalbach Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Inland canal Klingnau Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Surb Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Bünz Lp 1.000 Petite Camargue B2K6 genetics Sum 39.300 France L0 269.147 Allier 13457 Rhein (Alt-/Restrhein) L0 142.000 Rhine 7100 La 31.500 Rhine 3150 L0 5.000 Rhine 250 Doller La 21.900 Rhine 2190 L0 2.500 Rhine 125 Thur La 12.000 Rhine 1200 L0 2.500 Rhine 125 Lauch La 5.000 Rhine 500 Fecht und Zuflüsse L0 10.000 Rhine 500 La 39.000 Rhine 3900 L0 4.200 Rhine 210 Ill La 17.500 Rhine 1750 Giessen und Zuflüsse L0 10.000 Rhine 500 La 28.472 Rhine 2847 L0 10.500 Rhine 525 -

Council CNL(14)23 Annual Progress Report on Actions Taken

Agenda Item 6.1 For Information Council CNL(14)23 Annual Progress Report on Actions Taken Under Implementation Plans for the Calendar Year 2013 EU – Germany CNL(14)23 Annual Progress Report on Actions taken under Implementation Plans for the Calendar Year 2013 The primary purposes of the Annual Progress Reports are to provide details of: • any changes to the management regime for salmon and consequent changes to the Implementation Plan; • actions that have been taken under the Implementation Plan in the previous year; • significant changes to the status of stocks, and a report on catches; and • actions taken in accordance with the provisions of the Convention These reports will be reviewed by the Council. Please complete this form and return it to the Secretariat by 1 April 2014. The annual report 2013 is structured according to the catchments of the rivers Rhine, Ems, Weser and Elbe. Party: European Union Jurisdiction/Region: Germany 1: Changes to the Implementation Plan 1.1 Describe any proposed revisions to the Implementation Plan and, where appropriate, provide a revised plan. Item 3.3 - Provide an update on progress against actions relating to Aquaculture, Introductions and Transfers and Transgenics (section 4.8 of the Implementation Plan) - has been supplemented by a new measure (A2). 1.2 Describe any major new initiatives or achievements for salmon conservation and management that you wish to highlight. Rhine ICPR The 15th Conference of Rhine Ministers held on 28th October 2013 in Basel has agreed on the following points for the rebuilding of a self-sustainable salmon population in the Rhine system in its Communiqué of Ministers (www.iksr.org / International Cooperation / Conferences of Ministers): - Salmon stocking can be reduced step by step in parts of the River Sieg system in the lower reaches of the Rhine, even though such stocking measures on the long run remain absolutely essential in the upper reaches of the Rhine, in order to increase the number of returnees and to enhance the carefully starting natural reproduction. -

Natur Pur Am Westlichen Bodensee

Natur pur am westlichen Bodensee Aktiv unterwegs im Einklang mit der Natur! Natur pur am westlichen Bodensee 2 | Natur pur am westlichen Bodensee Inhalt NATUR ERLEBEN & ERFAHREN ................... 4 - 45 See & Wasser ......................................................... 5 - 11 Untersee und Rhein » Natura Trail Mindelsee: ............................ 12 - 13 Inseln & Halbinseln .......................................... 14 - 17 Inselhopping » Natura Trail Untersee: ............................... 18 - 19 Berge & Täler ...................................................... 20 - 25 Aussichtspunkte Hegauer Vulkanlandschaft » Premium-Wandern im Hegau ............... 26 - 27 Flora & Fauna .................................................... 28 - 37 Beobachtungsplattformen, Vogelwelt, Natura Trails, Ufervegetation und Bodensee- Vergissmeinicht, Wälder und Auen, Weinberge, Gemüsefelder, Streuobstwiesen und Obstfelder » Natura Trail Lifepfad Untersee .............. 38 - 39 Führungen & Veranstaltungen .................. 40 - 43 » Premiumwanderweg SeeGang ................ 44 - 45 NATUR SPÜREN ............................................. 46 - 53 Der westliche Bodensee bietet Natur- Jahreszeiten & Wetter Sonnenuntergänge, Nebel, Seegfrörne ..... 47 - 48 schätze auf engstem Raum mit Seen- Entspannung & Meditationen und Vulkanlandschaften, versteckten Yoga, Tai Chi, Qigong .................................... 49 - 51 Buchten, unberührten Ufern, ausge- » Natura Trail westlicher Bodensee ........ 52 - 53 dehnten Naturschutzgebieten und NATUR BEWAHREN -

Strategien Zur Wiedereinbürgerung Des Atlantischen Lachses

Restocking – Current and future practices Experience in Germany, success and failure Presentation by: Dr. Jörg Schneider, BFS Frankfurt, Germany Contents • The donor strains • Survival rates, growth and densities as indicators • Natural reproduction as evidence for success - suitability of habitat - ability of the source • Return rate as evidence for success • Genetics and quality of stocking material as evidence for success • Known and unknown factors responsible for failure - barriers - mortality during downstream migration - poaching - ship propellers - mortality at sea • Trends and conclusion Criteria for the selection of a donor-strain • Geographic (and genetic) distance to the donor stream • Spawning time of the donor stock • Length of donor river • Timing of return of the donor stock yesterdays environment dictates • Availability of the source tomorrows adaptations (G. de LEANIZ) • Health status and restrictions In 2003/2004 the strategy of introducing mixed stocks in single tributaries was abandoned in favour of using the swedish Ätran strain (Middle Rhine) and french Allier (Upper Rhine) only. Transplanted strains keep their inherited spawning time in the new environment for many generations - spawning time is stock specific. The timing of reproduction ensures optimal timing of hatching and initial feeding for the offspring (Heggberget 1988) and is of selective importance Spawning time of non-native stocks in river Gudenau (Denmark) (G. Holdensgaard, DCV, unpublished data) and spawning time of the extirpated Sieg salmon (hist. records) A common garden experiment - spawning period (lines) and peak-spawning (boxes) of five introduced (= allochthonous) stocks returning to river Gudenau (Denmark) (n= 443) => the Ätran strain demonstrates the closest consistency with the ancient Sieg strain (Middle Rhine). -

Rare Earth Elements As Emerging Contaminants in the Rhine River, Germany and Its Tributaries

Rare earth elements as emerging contaminants in the Rhine River, Germany and its tributaries by Serkan Kulaksız A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geochemistry Approved, Thesis Committee _____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Michael Bau, Chair Jacobs University Bremen _____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Andrea Koschinsky Jacobs University Bremen _____________________________________ Dr. Dieter Garbe-Schönberg Universität Kiel Date of Defense: June 7th, 2012 _____________________________________ School of Engineering and Science TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION 1 1. Outline 1 2. Research Goals 4 3. Geochemistry of the Rare Earth Elements 6 3.1 Controls on Rare Earth Elements in River Waters 6 3.2 Rare Earth Elements in Estuaries and Seawater 8 3.3 Anthropogenic Gadolinium 9 3.3.1 Controls on Anthropogenic Gadolinium 10 4. Demand for Rare Earth Elements 12 5 Rare Earth Element Toxicity 16 6. Study Area 17 7. References 19 Acknowledgements 28 CHAPTER II – SAMPLING AND METHODS 31 1. Sample Preparation 31 1.1 Pre‐concentration 32 2. Methods 34 2.1 HCO3 titration 34 2.2 Ion Chromatography 34 2.3 Inductively Coupled Plasma – Optical Emission Spectrometer 35 2.4 Inductively Coupled Plasma – Mass Spectrometer 35 2.4.1 Method reliability 36 3. References 41 CHAPTER III – RARE EARTH ELEMENTS IN THE RHINE RIVER, GERMANY: FIRST CASE OF ANTHROPOGENIC LANTHANUM AS A DISSOLVED MICROCONTAMINANT IN THE HYDROSPHERE 43 Abstract 44 1. Introduction 44 2. Sampling sites and Methods 46 2.1 Samples 46 2.2 Methods 46 2.3 Quantification of REE anomalies 47 3. Results and Discussion 48 4. -

Generalised Likelihood Uncertainty Estimation for the Daily HBV Model in the Rhine Basin, Part B: Switzerland

Generalised Likelihood Uncertainty Estimation for the daily HBV model in the Rhine Basin, Part B: Switzerland Deltares Title Generalised Likelihood Uncertainty Estimation for the daily HBV model in the Rhine Basin Client Project Reference Pages Rijkswaterstaat, WVL 1207771-003 1207771-003-ZWS-0017 29 Keywords GRADE, GLUE analysis, parameter uncertainty estimation, Switzerland Summary This report describes the derivation of a set of parameter sets for the HBV models for the Swiss part of the Rhine basin covering the catchment area upstream of Basel, including the uncertainty in these parameter sets. These parameter sets are required for the project "Generator of Rainfall And Discharge Extremes (GRADE)". GRADE aims to establish a new approach to define the design discharges flowing into the Netherlands from the Meuse and Rhine basins. The design discharge return periods are very high and GRADE establishes these by performing a long simulation using synthetic weather inputs. An additional aim of GRADE is to estimate the uncertainty of the resulting design discharges. One of the contributions to this uncertainty is the model parameter uncertainty, which is why the derivation of parameter uncertainty is required. Parameter sets, which represent the uncertainty, were derived using a Generalized Likelihood Uncertainty Estimation (GLUE), which conditions a prior parameter distribution by Monte Carlo sampling of parameter sets and conditioning on a modelled v.s. observed flow in selected flow stations. This analysis has been performed for aggregated sub-catchments (Rhein and Aare branch) separately using the HYRAS 2.0 rainfall dataset and E-OBS v4 temperature dataset as input and a discharge dataset from the BAFU (Bundesambt Für Umwelt) as flow observations. -

Internationally Coordinated Management Plan 2015 for the International River Basin District of the Rhine

Internationally Coordinated Management Plan 2015 for the International River Basin District of the Rhine (Part A = Overriding Part) December 2015 Imprint Joint report of The Republic of Italy, The Principality of Liechtenstein, The Federal Republic of Austria, The Federal Republic of Germany, The Republic of France, The Grand Duchy of Luxemburg, The Kingdom of Belgium, The Kingdom of the Netherlands With the cooperation of the Swiss Confederation Data sources Competent Authorities in the Rhine river basin district Coordination Rhine Coordination Committee in cooperation with the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) Drafting of maps Federal Institute of Hydrology, Koblenz, Germany Publisher: International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) Kaiserin-Augusta-Anlagen 15, D 56068 Koblenz P.O. box 20 02 53, D 56002 Koblenz Telephone +49-(0)261-94252-0, Fax +49-(0)261-94252-52 Email: [email protected] www.iksr.org Translation: Karin Wehner ISBN 978-3-941994-72-0 © IKSR-CIPR-ICBR 2015 IKSR CIPR ICBR Bewirtschaftungsplan 2015 IFGE Rhein Contents Introduction .................................................................................. 6 1. General description .............................................................. 8 1.1 Surface water bodies in the IRBD Rhine ................................................. 11 1.2 Groundwater ...................................................................................... 12 2. Human activities and stresses .......................................... -

"Matte" Und "Wiese" in Den Alemannischen Urkunden Des 13

"Matte" und "Wiese" in den alemannischen Urkunden des 13. Jahrhunderts Autor(en): Boesch, Bruno Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerisches Archiv für Volkskunde = Archives suisses des traditions populaires Band (Jahr): 42 (1945) PDF erstellt am: 07.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-114116 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch 49 „Matte" und „Wiese" in den alemannischen Urkunden des 13. Jahrhunderts. Von Bruno Boesch, Zürich. Die beiden Wörter sind ein eindrückliches Beispiel dafür, wie sich ein moderner sprachgeographischer Sachverhalt bereits in der mittelalterlichen Urkundensprache des 13. Jahrhunderts vollkommen abzeichnet. Die Verbreitung dieser beiden Wörter als Appellativa in den heutigen alemannischen und schwäbischen Mundarten hat Elisabeth Müller in Teuthonista 7, 162 if.