Skin Wound Healing: Normal Macrophage Function and Macrophage Dysfunction in Diabetic Wounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Energy Healing

57618_CH03_Pass2.QXD 10/30/08 1:19 PM Page 61 © Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION. CHAPTER 3 Energy Healing Our remedies oft in ourselves do lie. —WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE LEARNING OBJECTIVES 1. Describe the types of energy. 2. Explain the universal energy field (UEF). 3. Explain the human energy field (HEF). 4. Describe the seven auric layers. 5. Describe the seven chakras. 6. Define the concept of energy healing. 7. Describe various types of energy healing. INTRODUCTION For centuries, traditional healers worldwide have practiced methods of energy healing, viewing the body as a complex energy system with energy flowing through or over its surface (Rakel, 2007). Until recently, the Western world largely ignored the Eastern interpretation of humans as energy beings. However, times have changed dramatically and an exciting and promising new branch of academic inquiry and clinical research is opening in the area of energy healing (Oschman, 2000; Trivieri & Anderson, 2002). Scientists and energy therapists around the world have made discoveries that will forever alter our picture of human energetics. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is conducting research in areas such as energy healing and prayer, and major U.S. academic institutions are conducting large clinical trials in these areas. Approaches in exploring the concepts of life force and healing energy that previously appeared to compete or conflict have now been found to support each other. Conner and Koithan (2006) note 61 57618_CH03_Pass2.QXD 10/30/08 1:19 PM Page 62 © Jones and Bartlett Publishers, LLC. NOT FOR SALE OR DISTRIBUTION. 62 CHAPTER 3 • ENERGY HEALING that “with increased recognition and federal funding for energetic healing, there is a growing body of research that supports the use of energetic healing interventions with patients” (p. -

Purinergic Signalling in Skin

PURINERGIC SIGNALLING IN SKIN AINA VH GREIG MA FRCS Autonomic Neuroscience Institute Royal Free and University College School of Medicine Rowland Hill Street Hampstead London NW3 2PF in the Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology University College London Gower Street London WCIE 6BT 2002 Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of London ProQuest Number: U643205 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U643205 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT Purinergic receptors, which bind ATP, are expressed on human cutaneous kératinocytes. Previous work in rat epidermis suggested functional roles of purinergic receptors in the regulation of proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis, for example P2X5 receptors were expressed on kératinocytes undergoing proliferation and differentiation, while P2X? receptors were associated with apoptosis. In this thesis, the aim was to investigate the expression of purinergic receptors in human normal and pathological skin, where the balance between these processes is changed. A study was made of the expression of purinergic receptor subtypes in human adult and fetal skin. -

Wound Classification

Wound Classification Presented by Dr. Karen Zulkowski, D.N.S., RN Montana State University Welcome! Thank you for joining this webinar about how to assess and measure a wound. 2 A Little About Myself… • Associate professor at Montana State University • Executive editor of the Journal of the World Council of Enterstomal Therapists (JWCET) and WCET International Ostomy Guidelines (2014) • Editorial board member of Ostomy Wound Management and Advances in Skin and Wound Care • Legal consultant • Former NPUAP board member 3 Today We Will Talk About • How to assess a wound • How to measure a wound Please make a note of your questions. Your Quality Improvement (QI) Specialists will follow up with you after this webinar to address them. 4 Assessing and Measuring Wounds • You completed a skin assessment and found a wound. • Now you need to determine what type of wound you found. • If it is a pressure ulcer, you need to determine the stage. 5 Assessing and Measuring Wounds This is important because— • Each type of wound has a different etiology. • Treatment may be very different. However— • Not all wounds are clear cut. • The cause may be multifactoral. 6 Types of Wounds • Vascular (arterial, venous, and mixed) • Neuropathic (diabetic) • Moisture-associated dermatitis • Skin tear • Pressure ulcer 7 Mixed Etiologies Many wounds have mixed etiologies. • There may be both venous and arterial insufficiency. • There may be diabetes and pressure characteristics. 8 Moisture-Associated Skin Damage • Also called perineal dermatitis, diaper rash, incontinence-associated dermatitis (often confused with pressure ulcers) • An inflammation of the skin in the perineal area, on and between the buttocks, into the skin folds, and down the inner thighs • Scaling of the skin with papule and vesicle formation: – These may open, with “weeping” of the skin, which exacerbates skin damage. -

Wound Care: the Basics

Wound Care: The Basics Suzann Williams-Rosenthal, RN, MSN, WOC, GNP Norma Branham, RN, MSN, WOC, GNP University of Virginia May, 2010 What Type of Wound is it? How long has it been there? Acute-generally heal in a couple weeks, but can become chronic: Surgical Trauma Chronic -do not heal by normal repair process-takes weeks to months: Vascular-venous stasis, arterial ulcers Pressure ulcers Diabetic foot ulcers (neuropathic) Chronic Wounds Pressure Ulcer Staging Where is it? Where is it located? Use anatomical location-heel, ankle, sacrum, coccyx, etc. Measurements-in centimeters Length X Width X Depth • Length = greatest length (head to toe) • Width = greatest width (side to side) • Depth = measure by marking the depth with a Q- Tip and then hold to a ruler Wound Characteristics: Describe by percentage of each type of tissue: Granulation tissue: • red, cobblestone appearance (healing, filling in) Necrotic: • Slough-yellow, tan dead tissue (devitalized) • Eschar-black/brown necrotic tissue, can be hard or soft Evaluating additional tissue damage: Undermining Separation of tissue from the surface under the edge of the wound • Describe by clock face with patients head at 12 (“undermining is 1 cm from 12 to 4 o’clock”) Tunneling Channel that runs from the wound edge through to other tissue • “tunneling at 9 o’clock, measuring 3 cm long” Wound Drainage and Odor Exudate Fluid from wound • Document the amount, type and odor • Light, moderate, heavy • Drainage can be clear, sanguineous (bloody), serosanguineous (blood-tinged), -

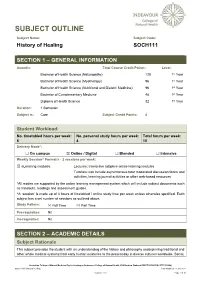

SOCH111 History of Healing Last Modified: 17-Jun-2021

SUBJECT OUTLINE Subject Name: Subject Code: History of Healing SOCH111 SECTION 1 – GENERAL INFORMATION Award/s: Total Course Credit Points: Level: Bachelor of Health Science (Naturopathy) 128 1st Year Bachelor of Health Science (Myotherapy) 96 1st Year Bachelor of Health Science (Nutritional and Dietetic Medicine) 96 1st Year Bachelor of Complementary Medicine 48 1st Year Diploma of Health Science 32 1st Year Duration: 1 Semester Subject is: Core Subject Credit Points: 4 Student Workload: No. timetabled hours per week: No. personal study hours per week: Total hours per week: 6 4 10 Delivery Mode*: ☐ On campus ☒ Online / Digital ☐ Blended ☐ Intensive Weekly Session^ Format/s - 2 sessions per week: ☒ eLearning modules: Lectures: Interactive adaptive online learning modules Tutorials: can include asynchronous tutor moderated discussion forum and activities, learning journal activities or other web-based resources *All modes are supported by the online learning management system which will include subject documents such as handouts, readings and assessment guides. ^A ‘session’ is made up of 3 hours of timetabled / online study time per week unless otherwise specified. Each subject has a set number of sessions as outlined above. Study Pattern: ☒ Full Time ☒ Part Time Pre-requisites: Nil Co-requisites: Nil SECTION 2 – ACADEMIC DETAILS Subject Rationale This subject provides the student with an understanding of the history and philosophy underpinning traditional and other whole medical systems from early human existence to the present day in diverse cultures worldwide. Social, Australian College of Natural Medicine Pty Ltd trading as Endeavour College of Natural Health, FIAFitnation (National CRICOS #00231G, RTO #31489) SOCH111 History of Healing Last modified: 17-Jun-2021 Version: 27.0 Page 1 of 10 cultural and political developments are considered in the evolution of healing and medicine, as well as the parallel developments in anatomy, physiology and other sciences. -

Collagen in Wound Healing

bioengineering Review Collagen in Wound Healing Shomita S. Mathew-Steiner, Sashwati Roy and Chandan K. Sen * Indiana Center for Regenerative Medicine and Engineering, School of Medicine, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA; [email protected] (S.S.M.-S.); [email protected] (S.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-317-278-2735 Abstract: Normal wound healing progresses through inflammatory, proliferative and remodeling phases in response to tissue injury. Collagen, a key component of the extracellular matrix, plays critical roles in the regulation of the phases of wound healing either in its native, fibrillar conformation or as soluble components in the wound milieu. Impairments in any of these phases stall the wound in a chronic, non-healing state that typically requires some form of intervention to guide the process back to completion. Key factors in the hostile environment of a chronic wound are persistent inflammation, increased destruction of ECM components caused by elevated metalloproteinases and other enzymes and improper activation of soluble mediators of the wound healing process. Collagen, being central in the regulation of several of these processes, has been utilized as an adjunct wound therapy to promote healing. In this work the significance of collagen in different biological processes relevant to wound healing are reviewed and a summary of the current literature on the use of collagen-based products in wound care is provided. Keywords: extracellular matrix; collagen; signaling; inflammation; wound healing; collagen dressings; engineered collagen Citation: Mathew-Steiner, S.S.; Roy, S.; Sen, C.K. Collagen in Wound 1. Introduction Healing. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 63. Sophisticated regulation by a number of key factors including the environment of the https://doi.org/10.3390/ wound which is rich in extracellular matrix (ECM) drives the process of wound healing [1,2]. -

Products & Technology Wound Inflammation and the Role of A

Products & technology Wound inflammation and the role of a multifunctional polymeric dressing Temporary inflammation is a normal response in acute wound healing. However, in chronic wounds, the inflammatory phase is dysfunctional in nature. This results in delayed healing, and causes further problems such as increased pain, odour and Intro high levels of exudate production. It is important to choose a dressing that addresses all of these factors while meeting the patient’s needs. Multifunctional polymeric Authors: Keith F Cutting membrane dressings (e.g. PolyMem®, Ferris) can help to simplify this choice and Authors: Peter Vowden assist healthcare professionals in chronic wound care. The unique actions of xxxxx Cornelia Wiegand PolyMem® have been proven to reduce and prevent inflammation, swelling, bruising and pain to promote rapid healing, working in the deep tissues beneath the skin[1,2]. he mechanism of acute wound healing — the vascular and cellular stages. During is a well-described complex cellular vascular response, immediately on injury there is T interaction[3] that can be divided into an initial transient vasoconstriction that can be several integrated processes: haemostasis, measured in seconds. This is promptly followed inflammation, proliferation, epithelialisation by vasodilation under the influence of histamine and tissue remodeling. Inflammation is a key and nitric oxide (NO) that cause an inflow of blood. component of acute wound healing, clearing An increase in vascular permeability promotes damaged extracellular matrix, cells and debris leakage of serous fluid (protein-rich exudate) into from zones of tissue damage. This is normally a the extravascular compartment, which in turn time-limited orchestrated process. Successful increases the concentration of cells and clotting progression of the inflammatory phase allows factors. -

Inflammation and Tendon Healing

Linköping University Medical Dissertation No. 1583 Inflammation and tendon healing Parmis Blomgran Division of Clinical Sciences Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Linköping University Linköping, Sweden 2017 © Parmis Blomgran 2017 Articles have been reprinted with permission of the respective copyright owners. Cover and title page illustration by Per Aspenberg During the course of research underlying this thesis, Parmis Blomgran was enrolled in Forum Scientium, a multidisciplinary doctoral program at Linköping University, Sweden. Printed by LiU-Tryck, Linköping, Sweden, 2017 ISBN: 978-91-7685-471-6 ISSN: 0345-0082 Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go T.S. Eliot Supervisor Per Aspenberg Professor, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Linköping University Co-supervisor Jan Ernerudh Professor, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Linköping University Faculty Opponent Patrik Danielson Professor, Department of Integrative Medical Biology, Umeå University Committee board Michael Kjaer Professor, Institute of Sports Medicine Copenhagen, Bispebjerg Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Denmark Torbjörn Bengtsson Professor, Department of Medical Sciences, Örebro University Lennart Svensson Professor, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Linköping University To my parents List of papers I. Blomgran P, Blomgran R, Ernerudh J, Aspenberg P A possible link between loading, inflammation and healing: Immune cell populations during tendon healing in the rat Scientific Reports. 2016; 6:29824 II. Blomgran P, Blomgran R, Ernerudh J, Aspenberg P COX-2 inhibition and the composition of inflammatory cell populations during early and mid-time tendon healing Muscle, Ligament and Tendons Journal. 2017; 7(2):223-229 III. -

Inflammation: the Normal Response to Injury an Editorial of the Natural

Walden University ScholarWorks School of Health Sciences Publications College of Health Sciences 2018 Inflammation: the normal esponser to injury an editorial of the natural healing qualities W. Sumner Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/shs_pubs Recommended Citation Davis, W. Sumner, "Inflammation: the normal esponser to injury an editorial of the natural healing qualities" (2018). School of Health Sciences Publications. 174. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/shs_pubs/174 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Health Sciences at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Health Sciences Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOJ Public Health Editorial Open Access Inflammation: the normal response to injury an editorial of the natural healing qualities Editorial Volume 7 Issue 4 - 2018 Last week, while out for a run, I felt a sharp pain in my knee. Inspection revealed no obvious biomechanical issue, and the pain W Sumner Davis was intermittent. Still I took it easy until I returned home. While the Walden University, USA area where I had felt the pain was swollen, it was not discolored. Discolored areas generally indicate the breakage of capillaries and Correspondence: W Sumner Davis, Community Psychologist small blood vessels under the skin. The black and blue areas are and Clinical Epidemiologist, Walden University, Oakland, ME caused by red blood cells and other contents of your circulatory 04963, USA, Tel +01(207) 740-2028, system. While bruising is a sign of trauma, swelling or inflammation Email [email protected] is a natural part of the body’s response to injury. -

Health and Healing Through Water Water Has Tremendous Healing

Kevin Ebner Health and Healing through Water Water has tremendous healing potential for the human mind, body and spirit. Water can physiologically and psychologically benefit people because of its therapeutic nature. For thousands of years it has been known to help cure illness, refresh the body and relax the mind. Since those ancient times water has been one of the most effective elements in combating illness and injury. Hydrotherapy, or water treatment, can combat many diseases or ailments, but it can also be a quick, easy and affordable way to relieve a little stress. As the most abundant resource on this planet, water should still be used for its ability to cure and help people in these times. Despite technological and medical advances of recent centuries does water still have the capacity to effectively promote good health and healing naturally? Water is the cheapest and most abundant resource we have because it can be found nearly anywhere on the planet. The United States Geological Survey estimates that nearly seventy percent of the surface of the earth is covered with water. It also falls regularly from the sky in various forms of precipitation over most of the land. Water is a necessary ingredient for any living being on this planet. The Web MD Medical Library states that the human body is between 60 and 70% water, therefore, it is logical that water would be a key factor in restoring the health of people. Most of human civilization can be found near lakes, coasts, river banks or other places in close proximity to a plentiful water source. -

Exercise Rehabilitation for Patients with Critical Limb Ischemia Peripheral

TITLE: Exercise rehabilitation for patients with critical limb ischemia peripheral arterial disease after revascularization: a single center pilot randomized controlled trial assessing quality of life and functional capacity after a 12-week rehabilitation program compared with best medical therapy BACKGROUND Definitions Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) refers to narrowing and occlusion of arteries supplying oxygenated blood to non-coronary and non-intracranial circulatory systems. This term is typically used to describe disease in the legs though it also affects upper extremities, renal and mesenteric vessels (Hiatt et al., 2008). Atherosclerosis is a key cause of PAD and is the main focus of this particular study. Other more rare conditions that can lead to PAD include anatomical/congenital variation, fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), vasculitides, trauma and localized radiation (Gerhard-Herman et al., 2017; Hirsch et al., 2006). PAD patients present with a wide range of symptoms. Patients who are non-ambulatory or with subclinical levels of disease may be asymptomatic and unaware of the disease process. Symptomatic patients typically experience leg pain with walking or physical activity, which is referred to as intermittent claudication (IC) (Dormandy & Rutherford, 2000; Hiatt et al., 2008; Norgren et al., 2007). In more advanced chronic disease states with severely compromised blood flow to the tissues, patients may have leg pain at rest or even non healing wounds that can lead to tissue loss which is defined as critical limb ischemia -

Role of Collagen in Wound Management

Clinical REVIEW Role of collagen in wound management Collagen is structurally and functionally a key protein of the extracellular matrix which is also involved in scar formation during the healing of connective tissues. Many collagen dressings have been developed to enhance wound repair, particularly of non-infected, chronic, indolent skin ulcers. The use of collagen dressings is supported by relatively sparse and insufficient scientific data. This review identifies the supporting evidence for the use of the dressings which are available, often with widely different claimed advantages and modes of action, and considers future developments and assessment of collagen dressings. Aravindan Rangaraj, Keith Harding, David Leaper The principal function of collagen is 8 Protein synthesis in the extracellular KEY WORDS to act as a scaffold in connective tissue, matrix (ECM) mostly in its type I, II and III forms. In 8 Synthesis and release of Collagen early healing wounds, type III is laid inflammatory cytokines and Wound healing down first, with the proportion of type growth factors Dressings I increasing as scar formation progresses 8 Interactions between enzymes which Chronic wounds and is remodelled. Collagen deposition remodel the ECM, including matrix and remodelling contribute to the metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their increased tensile strength of the wound, tissue inhibitors (TIMPs), which are which is approximately 20% of normal summarised in Table 1. by three weeks after injury, gradually ollagen is the unique, triple reaching a maximum