Wrongful Convictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impeachment with Unadjudicated Perjury: Deadly Than the Witnesses Ever Had Said!”2 Weapon Or Imaginary Beast?

Litigation News November 2016 Volume XVII, Number IX December 2016 Few Perjurers Are Prosecuted Impeachment with Although lying under oath is endemic, perjury is Unadjudicated Perjury: rarely prosecuted. When it is, the defendant is usu- ally a politician. The prosecution of Alger Hiss was Deadly Weapon or probably the most famous political perjury prosecu- tion ever in the United States. It made a young anti- Imaginary Beast? communist California Congressman named Richard Nixon a household name.3 The recent perjury by Robert E. Scully, Jr. conviction of Kathleen Kane, the Attorney General Stites & Harbison, PLLC of Pennsylvania, for lying about her role in leaking grand jury testimony to embarrass a political oppo- Impeaching a witness at trial with his prior nent is a modern case in point.4 More memorable untruthfulness under oath is the epitome of cross for those of us of a certain age, President Bill Clinton examination. When you do it, the day is glorious. testified falsely under oath in a judicially supervised When someone does it to your witness, your month deposition in a federal civil case that he did not have is ruined. Yet, this impeachment method is seldom sexual relations with Monica Lewinsky. He was not successfully employed. It is very like Lewis Carroll’s prosecuted for perjury despite being impeached by imaginary Snark, which when hunted could not be the House of Representatives, fined $900,000.00 for 1 caught: “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.” civil contempt by the presiding federal judge, and Only the unadjudicated perjurer can catch himself having had his Arkansas law license suspended for out on cross because “extrinsic evidence” of the act is five years for the falsehood.5 Absent some such prohibited. -

Police Misconduct As a Cause of Wrongful Convictions

POLICE MISCONDUCT AS A CAUSE OF WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS RUSSELL COVEY ABSTRACT This study gathers data from two mass exonerations resulting from major police scandals, one involving the Rampart division of the L.A.P.D., and the other occurring in Tulia, Texas. To date, these cases have received little systematic attention by wrongful convictions scholars. Study of these cases, however, reveals important differences among subgroups of wrongful convictions. Whereas eyewitness misidentification, faulty forensic evidence, jailhouse informants, and false confessions have been identified as the main contributing factors leading to many wrongful convictions, the Rampart and Tulia exonerees were wrongfully convicted almost exclusively as a result of police perjury. In addition, unlike other exonerated persons, actually innocent individuals charged as a result of police wrongdoing in Rampart or Tulia only rarely contested their guilt at trial. As is the case in the justice system generally, the great majority pleaded guilty. Accordingly, these cases stand in sharp contrast to the conventional wrongful conviction story. Study of these groups of wrongful convictions sheds new light on the mechanisms that lead to the conviction of actually innocent individuals. I. INTRODUCTION Police misconduct causes wrongful convictions. Although that fact has long been known, little else occupies this corner of the wrongful convictions universe. When is police misconduct most likely to result in wrongful convictions? How do victims of police misconduct respond to false allegations of wrongdoing or to police lies about the circumstances surrounding an arrest or seizure? How often do victims of police misconduct contest false charges at trial? How often do they resolve charges through plea bargaining? While definitive answers to these questions must await further research, this study seeks to begin the Professor of Law, Georgia State University College of Law. -

Police Perjury: a Factorial Survey

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey Author(s): Michael Oliver Foley Document No.: 181241 Date Received: 04/14/2000 Award Number: 98-IJ-CX-0032 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. FINAL-FINAL TO NCJRS Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey h4ichael Oliver Foley A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The City University of New York. 2000 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. I... I... , ii 02000 Michael Oliver Foley All Rights Reserved This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES GEORGE RAHSAAN BROOKS, Petitioner, COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA Respondent On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI George Rahsaan Brooks, pro se State Correction Institution Coal Township 1 Kelley Drive Coal Township, Pennsylvania 17866-1021 Identification Number: AP-4884 QUESTIONS PRESENTED WHETHER THE UNITED STATES HAS A SUBSTANTIAL INTEREST IN PREVENTING THE RISK OF INJUSTICE TO DEFENDANT AND AN IN- TEREST IN THE PUBLIC'S CONFIDENCE IN THE JUDICIAL PROCESS NOT BEING UNDERMINED? WHETHER THE STATE COURT'S DECISION CONCERNING BRADY LAW WAS AN UNREASONABLE APPLICATION OF CLEARLY ESTABLISHED FEDERAL LAW AS DETERMINED BY THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT? WHETHER THE STATE COURTS ENTERED A DECISION IN CONFLICT WITH ITS RULES OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURES, DECISIONAL LAW AND CONSTITU- TION ON THE SAME IMPORTANT MATTER AS WELL AS DECIDED AN IMPOR- TANT FEDERAL QUESTION ON NEWLY PRESENTED EVIDENCE IN A WAY THAT CONFLICTS WITH THIS COURT AND DEPARTED FROM THE AC- CEPTED AND USUAL COURSE OF JUDICIAL PROCEEDINGS AND FEDERAL LAW? a. WHETHER THE SUPERIOR'S COURT'S DECISION THAT CHARGING IN- STRUMENT IS NOT NEWLY PRESENTED EVIDENCE IS AN UNREASONABLE DETERMINATION OF FACTS IN LIGHT OF THE EVIDENCE PRESENTED TO THE STATE COURT AND AN UNREASONABLE APPLICATION OF FEDERAL LAW AS DETERMINED BY THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT? DID THE STATE COURT WILLFULLY FAIL TO DECIDE AN IMPORTANT QUESTION OF FEDERAL LAW AND THE CONSTITUTION ON FRAUD ON THE COURT WHICH HAS BEEN SETTLED BY FEDERAL LAW AND BY THIS COURT? I APPENDIX TABLE OF CONTENTS Commonwealth v. -

The Rampart Scandal

Human Rights Alert, NGO PO Box 526, La Verne, CA 91750 Fax: 323.488.9697; Email: [email protected] Blog: http://human-rights-alert.blogspot.com/ Scribd: http://www.scribd.com/Human_Rights_Alert 10-04-08 DRAFT 2010 UPR: Human Rights Alert (Ngo) - The United States Human Rights Record – Allegations, Conclusions, Recommendations. Executive Summary1 1. Allegations Judges in the United States are prone to racketeering from the bench, with full patronizing by US Department of Justice and FBI. The most notorious displays of such racketeering today are in: a) Deprivation of Liberty - of various groups of FIPs (Falsely Imprisoned Persons), and b) Deprivation of the Right for Property - collusion of the courts with large financial institutions in perpetrating fraud in the courts on homeowners. Consequently, whole regions of the US, and Los Angeles is provided as an example, are managed as if they were extra-constitutional zones, where none of the Human, Constitutional, and Civil Rights are applicable. Fraudulent computers systems, which were installed at the state and US courts in the past couple of decades are key enabling tools for racketeering by the judges. Through such systems they issue orders and judgments that they themselves never consider honest, valid, and effectual, but which are publicly displayed as such. Such systems were installed in violation of the Rule Making Enabling Act. Additionally, denial of Access to Court Records - to inspect and to copy – a First Amendment and a Human Right - is integral to the alleged racketeering at the courts - through concealing from the public court records in such fraudulent computer systems. -

From Dropsy to Testilying: Prosecutorial Apathy, Ennui, Or Complicity?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KnowledgeBank at OSU From Dropsy to Testilying: Prosecutorial Apathy, Ennui, or Complicity? Steven Zeidman* “To meet his constitutional and ethical obligations, a prosecutor should . approach the preparation of a case with a healthy skepticism . He should not assume his witnesses are telling the truth . .”1 “The often close relationship between prosecutors and police make detection of police fabrication unlikely.”2 “[Manhattan District Attorney] Vance’s efforts to make prosecutors smarter . depend on what he calls ‘extreme collaboration’ with the Police Department . working hand in glove with the investigators from the police . ”3 The prosecutor’s constitutional and ethical duty to truth is central to many of Bennett Gershman’s illuminating and trenchant articles about the role of the prosecutor.4 And while ruminating about that obligation conjures up the need for systematic and aggressive investigation while a criminal case is pending, in this essay I argue that nowhere is that duty more critical than at the very moment when a decision is made whether to file charges.5 Specifically, I argue that to meaningfully actualize their duty to truth, prosecutors must extricate themselves from their extant close relationships with the police by adopting a deliberately confrontational approach to police witnesses. Moreover, once a case is charged, they must overcome their longstanding reluctance to liberal disclosure by immediately providing defense counsel with all available discovery. Scholars have written about the complicated relationship between prosecutors * Professor, CUNY School of Law. J.D., Duke University School of Law. -

From Dropsy to Testilying: Prosecutorial Apathy, Ennui, Or Complicity?

From Dropsy to Testilying: Prosecutorial Apathy, Ennui, or Complicity? Steven Zeidman* “To meet his constitutional and ethical obligations, a prosecutor should . approach the preparation of a case with a healthy skepticism . He should not assume his witnesses are telling the truth . .”1 “The often close relationship between prosecutors and police make detection of police fabrication unlikely.”2 “[Manhattan District Attorney] Vance’s efforts to make prosecutors smarter . depend on what he calls ‘extreme collaboration’ with the Police Department . working hand in glove with the investigators from the police . ”3 The prosecutor’s constitutional and ethical duty to truth is central to many of Bennett Gershman’s illuminating and trenchant articles about the role of the prosecutor.4 And while ruminating about that obligation conjures up the need for systematic and aggressive investigation while a criminal case is pending, in this essay I argue that nowhere is that duty more critical than at the very moment when a decision is made whether to file charges.5 Specifically, I argue that to meaningfully actualize their duty to truth, prosecutors must extricate themselves from their extant close relationships with the police by adopting a deliberately confrontational approach to police witnesses. Moreover, once a case is charged, they must overcome their longstanding reluctance to liberal disclosure by immediately providing defense counsel with all available discovery. Scholars have written about the complicated relationship between prosecutors * Professor, CUNY School of Law. J.D., Duke University School of Law. I thank Mari Curbelo and Tom Klein for their encouragement, honest critique, and line edits. 1 Bennett L. -

Free Peltier?

Journal of Anti-Racist Action, Research & Education TURNINGVolume 12 Number 3 Fall 1999THE $2/newsstands TIDE In this issue: Puerto Rico*Shut Down the WTO!*ARA Mumia*Exchange on Zionism*Big Mountain*Police Brutality Free Peltier? People Against Racist Terror*PO Box 1055*Culver City 90232 310-288-5003*ISSN 1082-6491*e-mail: <[email protected]> PART'S Perspective: Puerto Rican Political Prisoners and Prisoners of War Released Que Viva Puerto Rico Libre! The forces of liberation and decolonization, and the campaign to free political emerged from prison gates for the first time in as much as 19 years. The campaign prisoners and prisoners of war held by the U.S., have won a tremendous victory. had united even Puerto Ricans who identified with commonwealth and statehood Eleven Puerto Rican political prisoners and prisoners of war were released from U.S. parties behind the demand for freedom for the independentistas. Prior to their release, prisons in September, under a conditional clemency by President Clinton. We must over 100,000 people marched in San Juan to demand that Clinton eliminate the savor the victory, and also deepen our understanding of how it was won and how it unjust and insulting conditions he was placing on their release. can be built on. An ecstatic crowd celebrated the released freedom fighters when they arrived in Edwin Cortes, Elizam Escobar, Ricardo Jimenez, Adolfo Matos, Dylcia Pagan, Puerto Rico. As TTT was going to press, the prisoners were scheduled to appear Alberto Rodriguez, Alicia Rodriguez, Ida Luz Rodriguez, Luis Rosa, Alejandrina together at a rally in Lares on September 23, commemorating the Grito de Lares, the Torres, and Carmen Valentin, were justly welcomed as heroes and patriots by the call for Puerto Rican independence from Spain. -

Successful Brady and Napue Cases

SUCCESSFUL BRADY/NAPUE CASES (Updated September 6, 2017) * capital case I. UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT *Wearry v. Cain 136 S.Ct. 1002 (2016) (per curiam) United States Supreme Court summarily reverses Louisiana court’s denial of postconviction relief on Brady claim, holding that state prejudicially failed to disclose material evidence including inmates’ statements casting doubt on the credibility of the testimony of the state’s key witnesses. Wearry was convicted by a jury of capital murder and sentenced to death, largely on the basis of testimony of two inmates, Scott and Brown, both of whose testimony was significantly different from the various statements they had provided to law enforcement prior to trial. There was no physical evidence linking Wearry to the crime and Wearry presented an alibi defense at trial. After Wearry’s conviction became final, he obtained information that the prosecution had withheld (1) police reports that indicated that one inmate had reported that Scott “wanted to make sure [Wearry] gets the needle cause he jacked over me” and another inmate lied to investigators at Scott’s urging, stating that he had witnessed the murder; (2) information that Brown had twice sought a deal to reduce his sentence in exchange for testifying against Wearry, and that the police had told him they would talk to the DA; and (3) medical records on Hutchinson, an individual whom Scott had reported ran into the street to flag down the victim on the night of the murder, pulled the victim out of the car, and shoved him into the cargo space and got into the cargo space himself. -

Incubating Monsters: Prosecutorial Responsibility for the Rampart Scandal

Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review Volume 34 Number 2 Symposium—The Rampart Scandal: Article 13 Policing the Criminal Justice System 1-1-2001 Incubating Monsters: Prosecutorial Responsibility for the Rampart Scandal Gary C. Williams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Gary C. Williams, Incubating Monsters: Prosecutorial Responsibility for the Rampart Scandal, 34 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 829 (2001). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/llr/vol34/iss2/13 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INCUBATING MONSTERS?: PROSECUTORIAL RESPONSIBILITY FOR TLE RAMPART SCANDAL Gary C. Williams* I. INTRODUCTION When disgraced former Los Angeles Police Officer Rafael Perez made his statement to the court after pleading guilty to stealing co- caine from a police storage locker, he uttered words that reverberated throughout the City of Los Angeles as it wrestled with the enormity of the scandal enveloping its chief law enforcement agency. After reciting in sordid detail his descent into a life of deceit, crime, and debauchery, Perez concluded his statement by declaring: "Whoever chases monsters should see to it that in the process he does -

Prevalence of Lying to Suspects During Interrogations and Police Perjury

MEMORANDUM TO: Clark Neily FROM: Andrew Eichen DATE: August 14, 2020 RE: Prevalence of lying to suspects during interrogations and police perjury. DISCUSSION I. THE USE OF DECEPTIVE INTERROGATION TACTICS IS COMMON IN THE UNITED STATES BECAUSE IT IS SANCTIONED BY THE LAW, UNLIKE IN OTHER COUNTRIES, SUCH AS ENGLAND AND GERMANY, WHERE THE PRACTICE IS OUTLAWED AND INCREDIBLY RARE. In the United States, the use of deception as a tool in interrogations in order to elicit a confession has become a routine practice for law enforcement. Today, virtually all interrogations in the United States, at least all successful interrogations, involve the use of police deception at least to some extent.1 Since the Supreme Court has put few limits on the practice, the varieties of deceptive techniques police may use are limited chiefly by officers’ ingenuity. 2 Deceptive techniques are taught to officers in interrogation manuals and sociological studies have confirmed that officers rely heavily on these practices, often to the exclusion of using other strategies.3 Since the practice is entirely legal, law enforcement officers freely admit to lying to suspects during interrogation. However, since the vast majority of cases in the United States end in guilty pleas, only a fraction of cases of police lying ever come to light. 4 The use of deception is so widespread among American police, that Richard Leo, a leading expert on police interrogations, has described it as “the single most salient and defining feature of how interrogation is practiced [in the United States].”5 To induce a confession, police rely on various different types of lies and forms of trickery during interrogation. -

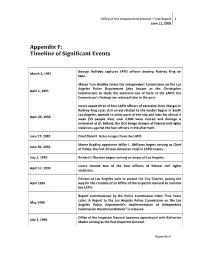

Appendix F: Timeline of Significant Events

Office of the Independent Monitor: Final Report 1 June 11, 2009 Appendix F: Timeline of Significant Events George Holliday captures LAPD officers beating Rodney King on March 2, 1991 tape. Mayor Tom Bradley forms the Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department (also known as the Christopher April 1, 1991 Commission) to study the excessive use of force in the LAPD; the Commission’s findings are released later in the year. Jurors acquit three of four LAPD officers of excessive force charges in Rodney King case; civil unrest related to the verdict begins in South Los Angeles, spreads to other parts of the city and lasts for almost a April 29, 1992 week (55 people died, over 2,000 were injured and damage is estimated at $1 billion); the DOJ brings charges of federal civil rights violations against the four officers in the aftermath. June 27, 1992 Chief Daryl F. Gates resigns from the LAPD. Mayor Bradley appointee Willie L. Williams begins serving as Chief June 30, 1992 of Police, the first African‐American chief in LAPD history. July 1, 1993 Richard J. Riordan begins serving as mayor of Los Angeles. Jurors convict two of the four officers of federal civil rights April 17, 1993 violations. Citizens of Los Angeles vote to amend the City Charter, paving the April 1995 way for the creation of an Office of the Inspector General to monitor the LAPD. Report commissioned by the Police Commission titled “Five Years Later: A Report to the Los Angeles Police Commission on the Los May 1996 Angeles Police Department’s Implementation of Independent Commission Recommendations” is released.