2018-04-25 Conducting Effective Voir Dire on Issues of Race Handouts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impeachment with Unadjudicated Perjury: Deadly Than the Witnesses Ever Had Said!”2 Weapon Or Imaginary Beast?

Litigation News November 2016 Volume XVII, Number IX December 2016 Few Perjurers Are Prosecuted Impeachment with Although lying under oath is endemic, perjury is Unadjudicated Perjury: rarely prosecuted. When it is, the defendant is usu- ally a politician. The prosecution of Alger Hiss was Deadly Weapon or probably the most famous political perjury prosecu- tion ever in the United States. It made a young anti- Imaginary Beast? communist California Congressman named Richard Nixon a household name.3 The recent perjury by Robert E. Scully, Jr. conviction of Kathleen Kane, the Attorney General Stites & Harbison, PLLC of Pennsylvania, for lying about her role in leaking grand jury testimony to embarrass a political oppo- Impeaching a witness at trial with his prior nent is a modern case in point.4 More memorable untruthfulness under oath is the epitome of cross for those of us of a certain age, President Bill Clinton examination. When you do it, the day is glorious. testified falsely under oath in a judicially supervised When someone does it to your witness, your month deposition in a federal civil case that he did not have is ruined. Yet, this impeachment method is seldom sexual relations with Monica Lewinsky. He was not successfully employed. It is very like Lewis Carroll’s prosecuted for perjury despite being impeached by imaginary Snark, which when hunted could not be the House of Representatives, fined $900,000.00 for 1 caught: “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.” civil contempt by the presiding federal judge, and Only the unadjudicated perjurer can catch himself having had his Arkansas law license suspended for out on cross because “extrinsic evidence” of the act is five years for the falsehood.5 Absent some such prohibited. -

Bad Cops: a Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers Author(s): James J. Fyfe ; Robert Kane Document No.: 215795 Date Received: September 2006 Award Number: 96-IJ-CX-0053 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Bad Cops: A Study of Career-Ending Misconduct Among New York City Police Officers James J. Fyfe John Jay College of Criminal Justice and New York City Police Department Robert Kane American University Final Version Submitted to the United States Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice February 2005 This project was supported by Grant No. 1996-IJ-CX-0053 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of views in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

MISCARRIAGES of JUSTICE ORIGINATING from DISCLOSURE DEFICIENCIES in CRIMINAL CASES A. Disclosure Failures As Ground for Retria

CHAPTER FOUR MISCARRIAGES OF JUSTICE ORIGINATING FROM DISCLOSURE DEFICIENCIES IN CRIMINAL CASES A. Disclosure Failures as Ground for Retrials: Common Law Standards and Examples This chapter will delve more deeply into one of the most fundamental causes of miscarriages of justice in (international) criminal cases, namely failure on the part of police and/or prosecution to timely, adequately and fairly disclose potentially exculpatory evidence to the judge, juries, and defense. The U.S. National Registry of Exonerations (NRE) which keeps count of exonerations in the U.S. from 1989 onwards, does not – in its offi- cial counting – include cases of group exonerations due to police and prosecutorial misconduct. In its June 2012-report the NRE counted 901 exonerations, the number has risen to 1,000 exonerations only five months later.1 The report discusses cases of at least 1,100 defendants who were exonerated in the so-called “group exonerations”. These exonerations were the consequence of the revelation of gross police misconduct in twelve cases since 1995 in which innocent defendants had been framed by police officers for mostly drug and gun crimes.2 Yet, most of the group exonera- tions were spotted accidently, as the cases are obscure and for some of the scandals the number of exonerees could only be estimated; these num- bers are not included in the 1,000 exonerations the registry counted on 30 October 2012.3 In many cases it will be hard to establish that police or prosecutorial misconduct did in fact occur; a conclusion that was also drawn by the NRE. This chapter will delve into cases where misconduct did come to light while analyzing the criminal law proceedings which led to these errors. -

Charter Commission Public Safety Comments July 20

7/20/2020 4:04:40 PM My name is 00000 00000000, and I am a resident of Minneapolis. I support divestment from police and reinvestment in our communities, and I am calling on the Charter Commission to let the people vote on the charter amendment. Over-policing and police violence have destroyed Black, brown and Indigenous communities while failing to keep us safe. Voters like me should have a role in determining the future of public safety in our city, because we know best what will allow all our neighborhoods to really thrive. This initiative is our best chance to build stronger, safer communities for everyone in Minneapolis. Please pass the charter amendment along to voters, and respect our democratic right to decide the future of our city. Ward 3 7/20/2020 4:04:51 PM I'm a member of Kenwood community, and I’d like to voice my support for the charter amendment to change the way our city handles public safety. To push the vote back another year is an act of disrespect and hate toward the marginalized people who are most impacted by the oppressive nature of our current system. Any member of the commission who thinks that waiting is best will lose the respect of the people they represent. Please listen to the calls of the people and allow this change to go through this year. Let the people decide for themselves! Ward 7 7/20/2020 4:06:35 PM I support the charter commission moving the current language of the amendment to a ballot vote in November. -

Water-Saving Ideas Rejected at Meeting

THE TWEED SHIRE Volume 2 #15 Thursday, December 10, 2009 Advertising and news enquiries: Phone: (02) 6672 2280 Our new Fax: (02) 6672 4933 property guide [email protected] starts on page 19 [email protected] www.tweedecho.com.au LOCAL & INDEPENDENT Water-saving ideas Restored biplane gets the thumbs up rejected at meeting Luis Feliu years has resulted in new or modified developments having rainwater tanks Water-saving options for Tweed resi- to a maximum of 3,000 litres but re- dents such as rainwater tanks, recy- stricted to three uses: washing, toilet cling, composting toilets as well as flushing and external use. Rainwater population caps were suggested and tanks were not permitted in urban rejected at a public meeting on Mon- areas to be used for drinking water day night which looked at Tweed Some residents interjected, saying Shire Council’s plan to increase the that was ‘absurd’ and asked ‘why not?’ shire’s water supply. while others said 3,000 litres was too Around 80 people attended the small. meeting at Uki Hall, called by the Mr Burnham said council’s water Caldera Environment Centre and af- demand management strategy had fected residents from Byrrill Creek identified that 5,000-litre rainwater concerned about the proposal to dam tanks produced a significant decrease their creek, one of four options under in overall demand but council had no discussion to increase the shire’s water power to enforce their use. supply. The other options are rais- Reuse not explored Nick Challinor, left, and Steve Searle guide the Tiger -

Police Perjury: a Factorial Survey

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey Author(s): Michael Oliver Foley Document No.: 181241 Date Received: 04/14/2000 Award Number: 98-IJ-CX-0032 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. FINAL-FINAL TO NCJRS Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey h4ichael Oliver Foley A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The City University of New York. 2000 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. I... I... , ii 02000 Michael Oliver Foley All Rights Reserved This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Promotion and Protection of the Human Rights and Fundamental

Written Submission prepared by the International Human Rights Clinic at Santa Clara University School of Law for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights’ Call for Input on the Promotion and protection of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of Africans and people of African descent against excessive use of force and other human rights violations by law enforcement officers pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution 43/1 International Human Rights Clinic at Santa Clara Law 500 El Camino Real Santa Clara, CA 95053-0424 U.S.A. Tel: +1 (408) 554-4770 [email protected] http://law.scu.edu/ihrc/ Diann Jayakoddy, Student Maxwell Nelson, Student Sukhvir Kaur, Student Prof. Francisco J. Rivera Juaristi, Director December 4, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION 3 II. IN A FEDERALIST SYSTEM, STATES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS MUST EXERCISE THEIR AUTHORITY TO REFORM LAWS ON POLICE ACCOUNTABILITY AND ON RESTRICTING THE USE OF FORCE BY POLICE OFFICERS 4 A.Constitutional standards on the use of force by police officers 5 B.Federal law governing police accountability 6 C.State police power 7 D.Recommendations 9 III. STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS MUST LIMIT THE ROLE OF POLICE UNIONS IN OBSTRUCTING EFFORTS TO HOLD POLICE OFFICERS ACCOUNTABLE IN THE UNITED STATES 9 A.Police union contracts limit accountability and create investigatory and other hurdles 10 1.Police unions can impede change 11 2.Police unions often reinforce a culture of impunity 12 B.Recommendations 14 IV. INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS OBLIGATIONS REGARDING NON-DISCRIMINATION AND THE PROTECTION OF THE RIGHTS TO LIFE, HEALTH, AND SECURITY REQUIRE DIVESTMENT OF POLICE DEPARTMENT FUNDING AND REINVESTMENT IN COMMUNITIES AND SERVICES IN THE UNITED STATES 14 A.“Defunding the Police” - a Movement Calling for the Divestment of Police Department Funding in the United States and Reinvestment in Communities 15 B.Recommendations 18 2 I. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES GEORGE RAHSAAN BROOKS, Petitioner, COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA Respondent On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI George Rahsaan Brooks, pro se State Correction Institution Coal Township 1 Kelley Drive Coal Township, Pennsylvania 17866-1021 Identification Number: AP-4884 QUESTIONS PRESENTED WHETHER THE UNITED STATES HAS A SUBSTANTIAL INTEREST IN PREVENTING THE RISK OF INJUSTICE TO DEFENDANT AND AN IN- TEREST IN THE PUBLIC'S CONFIDENCE IN THE JUDICIAL PROCESS NOT BEING UNDERMINED? WHETHER THE STATE COURT'S DECISION CONCERNING BRADY LAW WAS AN UNREASONABLE APPLICATION OF CLEARLY ESTABLISHED FEDERAL LAW AS DETERMINED BY THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT? WHETHER THE STATE COURTS ENTERED A DECISION IN CONFLICT WITH ITS RULES OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURES, DECISIONAL LAW AND CONSTITU- TION ON THE SAME IMPORTANT MATTER AS WELL AS DECIDED AN IMPOR- TANT FEDERAL QUESTION ON NEWLY PRESENTED EVIDENCE IN A WAY THAT CONFLICTS WITH THIS COURT AND DEPARTED FROM THE AC- CEPTED AND USUAL COURSE OF JUDICIAL PROCEEDINGS AND FEDERAL LAW? a. WHETHER THE SUPERIOR'S COURT'S DECISION THAT CHARGING IN- STRUMENT IS NOT NEWLY PRESENTED EVIDENCE IS AN UNREASONABLE DETERMINATION OF FACTS IN LIGHT OF THE EVIDENCE PRESENTED TO THE STATE COURT AND AN UNREASONABLE APPLICATION OF FEDERAL LAW AS DETERMINED BY THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT? DID THE STATE COURT WILLFULLY FAIL TO DECIDE AN IMPORTANT QUESTION OF FEDERAL LAW AND THE CONSTITUTION ON FRAUD ON THE COURT WHICH HAS BEEN SETTLED BY FEDERAL LAW AND BY THIS COURT? I APPENDIX TABLE OF CONTENTS Commonwealth v. -

Barriers to Identifying Police Misconduct

Barriers to Identifying Police Misconduct A Series on Police Accountability and Union Contracts by the Coalition for Police Contracts Accountability Barriers to Identifying Police Misconduct Introduction The Problem For decades, the Chicago Police department has had a “code of silence” that allows officers to hide misconduct. The Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) Lodge 7 and the Illinois Policemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association (PBPA) union contracts with the City of Chicago effectively make this “code of silence” official policy, making it too hard to identify police misconduct and too easy for police officers to lie about it and hide it. Both the Department of Justice and the Police Accountability Task Force have raised serious concerns about provisions in the police contracts, and Mayor Rahm Emanuel has acknowledged that the "code of silence" is a barrier to reform of the police department. Until the harmful provisions in the police contracts are changed, police officers will continue to operate under a separate system of justice. The Coalition The Coalition for Police Contracts Accountability (CPCA) proposes critical changes to the police union contracts and mobilizes communities to demand that new contracts between the City of Chicago and police unions don’t stand in the way of holding officers accountable. We are composed of community, policy, and civil rights organizations taking action to ensure police accountability in the city of Chicago. This Report CPCA has proposed 14 critical reforms to Chicago’s police union contracts which, collectively, can have a significant impact in ending the code of silence and increasing police accountability. This report is the first of five reports that the CPCA will publish presenting substantial evidence in support of each of our 14 recommendations. -

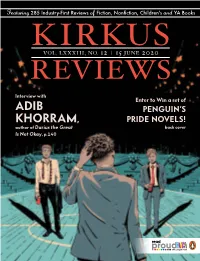

Kirkus Reviews

Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS Interview with Enter to Win a set of ADIB PENGUIN’S KHORRAM, PRIDE NOVELS! author of Darius the Great back cover Is Not Okay, p.140 with penguin critically acclaimed lgbtq+ reads! 9780142425763; $10.99 9780142422939; $10.99 9780803741072; $17.99 “An empowering, timely “A narrative H“An empowering, timely story with the power to experience readers won’t story with the power to help readers.” soon forget.” help readers.” —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews —Kirkus Reviews, starred review A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION WINNER OF THE STONEWALL A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION BOOK AWARD WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL WINNER OF THE PRINTZ MEDAL 9780147511478; $9.99 9780425287200; $22.99 9780525517511; $8.99 H“Enlightening, inspiring, “Read to remember, “A realistic tale of coming and moving.” remember to fight, fight to terms and coming- —Kirkus Reviews, starred review together.” of-age… with a touch of —Kirkus Reviews magic and humor” A RAINBOW LIST SELECTION —Kirkus Reviews Featuring 285 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children’s,and YA Books. KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 12 | 15 JUNE 2020 REVIEWS THE PRIDEISSUE Books that explore the LGBTQ+ experience Interviews with Meryl Wilsner, Meredith Talusan, Lexie Bean, MariNaomi, L.C. Rosen, and more from the editor’s desk: Our Books, Ourselves Chairman HERBERT SIMON BY TOM BEER President & Publisher MARC WINKELMAN John Paraskevas # As a teenager, I stumbled across a paperback copy of A Boy’s Own Story Chief Executive Officer on a bookstore shelf. Edmund White’s 1982 novel, based loosely on his MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] coming-of-age, was already on its way to becoming a gay classic—but I Editor-in-Chief didn’t know it at the time. -

The Seven (At Least) Lessons of the Myon Burrell Case

The Seven (at least) Lessons of the Myon Burrell Case LESLIE E. REDMOND & MARK OSLER I. INTRODUCTION For much of the world, 2020 was a troubling year, but few places saw as much uproar as Minnesota. The police killing of George Floyd set off protests in Minnesota and around the world,1 even as a pandemic and economic downturn hit minority communities with particular force.2 But, somehow, the year ended with an event that provided hope, promise, and a path to healing. On December 15, 2020, the Minnesota Board of Pardons granted a commutation of sentence to Myon Burrell, who had been convicted of murder and attempted murder and sentenced to life in prison.3 The Burrell case, closely examined, is a Pandora’s box containing many of the most pressing issues in criminal justice: racial disparities, the troubling treatment of juveniles, mandatory minimums, the power (and, too often, lack) of advocacy, the potential for conviction and sentencing review units, clemency, and the need for multiple avenues of second-look sentencing. The purpose of this essay is to briefly explore each of these in the context of this one remarkable case, and to use this example to make a 1 Damien Cave, Livia Albeck-Ripka & Iliana Magra, Huge Crowds Around the Globe March in Solidarity Against Police Brutality, N.Y. TIMES, (June 6, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/06/world/george-floyd-global-protests.html. 2 Heather Long, Andrew Van Dam, Alyssa Fowers & Leslie Shapiro, The COVID-19 Recession is the Most Unequal in Modern U.S. -

Blue Lives Matter

COP FRAGILITY AND BLUE LIVES MATTER Frank Rudy Cooper* There is a new police criticism. Numerous high-profile police killings of unarmed blacks between 2012–2016 sparked the movements that came to be known as Black Lives Matter, #SayHerName, and so on. That criticism merges race-based activism with intersectional concerns about violence against women, including trans women. There is also a new police resistance to criticism. It fits within the tradition of the “Blue Wall of Silence,” but also includes a new pro-police movement known as Blue Lives Matter. The Blue Lives Matter movement makes the dubious claim that there is a war on police and counter attacks by calling for making assaults on police hate crimes akin to those address- ing attacks on historically oppressed groups. Legal scholarship has not comprehensively considered the impact of the new police criticism on the police. It is especially remiss in attending to the implications of Blue Lives Matter as police resistance to criticism. This Article is the first to do so. This Article illuminates a heretofore unrecognized source of police resistance to criticism by utilizing diversity trainer and New York Times best-selling author Robin DiAngelo’s recent theory of white fragility. “White fragility” captures many whites’ reluctance to discuss ongoing rac- ism, or even that whiteness creates a distinct set of experiences and per- spectives. White fragility is based on two myths: the ideas that one could be an unraced and purely neutral individual—false objectivity—and that only evil people perpetuate racial subordination—bad intent theory. Cop fragility is an analogous oversensitivity to criticism that blocks necessary conversations about race and policing.