Prevalence of Lying to Suspects During Interrogations and Police Perjury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impeachment with Unadjudicated Perjury: Deadly Than the Witnesses Ever Had Said!”2 Weapon Or Imaginary Beast?

Litigation News November 2016 Volume XVII, Number IX December 2016 Few Perjurers Are Prosecuted Impeachment with Although lying under oath is endemic, perjury is Unadjudicated Perjury: rarely prosecuted. When it is, the defendant is usu- ally a politician. The prosecution of Alger Hiss was Deadly Weapon or probably the most famous political perjury prosecu- tion ever in the United States. It made a young anti- Imaginary Beast? communist California Congressman named Richard Nixon a household name.3 The recent perjury by Robert E. Scully, Jr. conviction of Kathleen Kane, the Attorney General Stites & Harbison, PLLC of Pennsylvania, for lying about her role in leaking grand jury testimony to embarrass a political oppo- Impeaching a witness at trial with his prior nent is a modern case in point.4 More memorable untruthfulness under oath is the epitome of cross for those of us of a certain age, President Bill Clinton examination. When you do it, the day is glorious. testified falsely under oath in a judicially supervised When someone does it to your witness, your month deposition in a federal civil case that he did not have is ruined. Yet, this impeachment method is seldom sexual relations with Monica Lewinsky. He was not successfully employed. It is very like Lewis Carroll’s prosecuted for perjury despite being impeached by imaginary Snark, which when hunted could not be the House of Representatives, fined $900,000.00 for 1 caught: “For the Snark was a Boojum, you see.” civil contempt by the presiding federal judge, and Only the unadjudicated perjurer can catch himself having had his Arkansas law license suspended for out on cross because “extrinsic evidence” of the act is five years for the falsehood.5 Absent some such prohibited. -

Representations and Discourse of Torture in Post 9/11 Television: an Ideological Critique of 24 and Battlestar Galactica

REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSE OF TORTURE IN POST 9/11 TELEVISION: AN IDEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF 24 AND BATTLSTAR GALACTICA Michael J. Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Committee: Jeffrey Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown Advisor Through their representations of torture, 24 and Battlestar Galactica build on a wider political discourse. Although 24 began production on its first season several months before the terrorist attacks, the show has become a contested space where opinions about the war on terror and related political and military adventures are played out. The producers of Battlestar Galactica similarly use the space of television to raise questions and problematize issues of war. Together, these two television shows reference a long history of discussion of what role torture should play not just in times of war but also in a liberal democracy. This project seeks to understand the multiple ways that ideological discourses have played themselves out through representations of torture in these television programs. This project begins with a critique of the popular discourse of torture as it portrayed in the popular news media. Using an ideological critique and theories of televisual realism, I argue that complex representations of torture work to both challenge and reify dominant and hegemonic ideas about what torture is and what it does. This project also leverages post-structural analysis and critical gender theory as a way of understanding exactly what ideological messages the programs’ producers are trying to articulate. -

Police Perjury: a Factorial Survey

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey Author(s): Michael Oliver Foley Document No.: 181241 Date Received: 04/14/2000 Award Number: 98-IJ-CX-0032 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. FINAL-FINAL TO NCJRS Police Perjury: A Factorial Survey h4ichael Oliver Foley A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The City University of New York. 2000 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. I... I... , ii 02000 Michael Oliver Foley All Rights Reserved This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Inspiring Americans to Greatness Attendees of the 2019 Freedom Conference Raise Their Hands in Solidarity with Hong Kong Pro-Democracy Protesters

Annual Report 2019-20 Inspiring Americans to Greatness Attendees of the 2019 Freedom Conference raise their hands in solidarity with Hong Kong pro-democracy protesters The principles espoused by The Steamboat Institute are: Limited taxation and fiscal responsibility • Limited government • Free market capitalism Individual rights and responsibilities • Strong national defense Contents INTRODUCTION EMERGING LEADERS COUNCIL About the Steamboat Institute 2 Meet Our Emerging Leaders 18 Letter from the Chairman 3 MEDIA COVERAGE AND OUTREACH AND EVENTS PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT Campus Liberty Tour 4 Media Coverage 20 Freedom Conferences and Film Festival 8 Social Media Analytics 21 Additional Outreach 10 FINANCIALS TONY BLANKLEY FELLOWSHIP 2019-20 Revenue & Expenses 22 FOR PUBLIC POLICY & AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM FUNDING About the Tony Blankley Fellowship 11 2019 and 2020 Fellows 12 Funding Sources 23 Past Fellows 14 MEET OUR PEOPLE COURAGE IN EDUCATION AWARD Board of Directors 24 Recipients 16 National Advisory Board 24 Our Team 24 The Steamboat Institute 2019-20 Annual Report – 1 – About The Steamboat Institute Here at the Steamboat Institute, we are Defenders of Freedom When we started The Steamboat Institute in 2008, it was and Advocates of Liberty. We are admirers of the bravery out of genuine concern for the future of our country. We take and rugged individualism that has made this country great. seriously the concept that freedom is never more than one We are admirers of the greatness and wisdom that resides generation away from extinction. in every individual. We understand that this is a great nation because of its people, not because of its government. The Steamboat Institute has succeeded beyond anything Like Thomas Jefferson, we would rather be, “exposed to we could have imagined when we started in 2008. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES GEORGE RAHSAAN BROOKS, Petitioner, COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA Respondent On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI George Rahsaan Brooks, pro se State Correction Institution Coal Township 1 Kelley Drive Coal Township, Pennsylvania 17866-1021 Identification Number: AP-4884 QUESTIONS PRESENTED WHETHER THE UNITED STATES HAS A SUBSTANTIAL INTEREST IN PREVENTING THE RISK OF INJUSTICE TO DEFENDANT AND AN IN- TEREST IN THE PUBLIC'S CONFIDENCE IN THE JUDICIAL PROCESS NOT BEING UNDERMINED? WHETHER THE STATE COURT'S DECISION CONCERNING BRADY LAW WAS AN UNREASONABLE APPLICATION OF CLEARLY ESTABLISHED FEDERAL LAW AS DETERMINED BY THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT? WHETHER THE STATE COURTS ENTERED A DECISION IN CONFLICT WITH ITS RULES OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURES, DECISIONAL LAW AND CONSTITU- TION ON THE SAME IMPORTANT MATTER AS WELL AS DECIDED AN IMPOR- TANT FEDERAL QUESTION ON NEWLY PRESENTED EVIDENCE IN A WAY THAT CONFLICTS WITH THIS COURT AND DEPARTED FROM THE AC- CEPTED AND USUAL COURSE OF JUDICIAL PROCEEDINGS AND FEDERAL LAW? a. WHETHER THE SUPERIOR'S COURT'S DECISION THAT CHARGING IN- STRUMENT IS NOT NEWLY PRESENTED EVIDENCE IS AN UNREASONABLE DETERMINATION OF FACTS IN LIGHT OF THE EVIDENCE PRESENTED TO THE STATE COURT AND AN UNREASONABLE APPLICATION OF FEDERAL LAW AS DETERMINED BY THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT? DID THE STATE COURT WILLFULLY FAIL TO DECIDE AN IMPORTANT QUESTION OF FEDERAL LAW AND THE CONSTITUTION ON FRAUD ON THE COURT WHICH HAS BEEN SETTLED BY FEDERAL LAW AND BY THIS COURT? I APPENDIX TABLE OF CONTENTS Commonwealth v. -

Alan Dershowitz

Debunking the Newest – and Oldest – Jewish Conspiracy: A Reply to the Mearsheimer-Walt “Working Paper” Alan Dershowitz Harvard Law School April 2006 The author of this paper is solely responsible for the views expressed in it. As an academic institution, Harvard University does not take a position on the scholarship of individual faculty members, and this paper should not be interpreted or portrayed as reflecting the official position of the University or any of its Schools. L:\Research\Sponsored Research\WP RR RAO\WP response paper\Dershowitz.response.paper.doc Words count: 9733 Last printed 4/5/2006 1:13:00 PM Created on 4/5/2006 1:08:00 PM Page 1 of 45 Debunking the Newest – and Oldest – Jewish Conspiracy1: A Reply to the Mearsheimer-Walt “Working Paper” by Alan Dershowitz2 Introduction The publication, on the Harvard Kennedy School web site, of a “working paper,” written by a professor and academic dean at the Kennedy School and a prominent professor at the University of Chicago, has ignited a hailstorm of controversy and raised troubling questions. The paper was written by two self-described foreign-policy “realists,” Professor Stephen Walt and Professor John Mearsheimer.3 It asserts that the Israel “Lobby” – a cabal whose “core” is “American Jews” – has a “stranglehold” on mainstream American media, think tanks, academia, and the government.4 The Lobby is led by the American-Israel Public Affairs Committee (“AIPAC”), which the authors characterize as a “de facto agent of a foreign government” that places the interests of that government ahead of the interests of the United States.5 Jewish political contributors use Jewish “money” to blackmail government officials, while “Jewish philanthropists” influence and “police” academic programs and shape public opinion.6 Jewish “congressional staffers” exploit their roles and betray the trust of their bosses by 1 Article citations reference John J. -

The Exceptional Absence of Human Rights As a Principle in American Law

Pace Law Review Volume 34 Issue 2 Spring 2014 Article 5 April 2014 The Exceptional Absence of Human Rights as a Principle in American Law Mugambi Jouet Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Mugambi Jouet, The Exceptional Absence of Human Rights as a Principle in American Law, 34 Pace L. Rev. 688 (2014) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/plr/vol34/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Exceptional Absence of Human Rights as a Principle in American Law Mugambi Jouet* I. Introduction References to “human rights” are rare in American civil or criminal cases, including those addressing fundamental questions of justice. In the United States, human rights often evoke abuses faced by people in Third World dictatorships. In other words, human rights commonly refer to foreign problems, not domestic ones. The relative absence of human rights as a concept in American law is peculiar by international standards, as human rights play a far greater role in the domestic systems of other Western democracies. This Article begins with a survey of references to “human rights” in landmark Supreme Court cases concerning racial segregation, the death penalty, prisoners’ rights, women’s rights, children’s rights, gay rights, and the indefinite detention of alleged terrorists during the “War on Terror.” The survey reveals that even liberal Justices seldom or never invoked “human rights” in these cases. -

From Dropsy to Testilying: Prosecutorial Apathy, Ennui, Or Complicity?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KnowledgeBank at OSU From Dropsy to Testilying: Prosecutorial Apathy, Ennui, or Complicity? Steven Zeidman* “To meet his constitutional and ethical obligations, a prosecutor should . approach the preparation of a case with a healthy skepticism . He should not assume his witnesses are telling the truth . .”1 “The often close relationship between prosecutors and police make detection of police fabrication unlikely.”2 “[Manhattan District Attorney] Vance’s efforts to make prosecutors smarter . depend on what he calls ‘extreme collaboration’ with the Police Department . working hand in glove with the investigators from the police . ”3 The prosecutor’s constitutional and ethical duty to truth is central to many of Bennett Gershman’s illuminating and trenchant articles about the role of the prosecutor.4 And while ruminating about that obligation conjures up the need for systematic and aggressive investigation while a criminal case is pending, in this essay I argue that nowhere is that duty more critical than at the very moment when a decision is made whether to file charges.5 Specifically, I argue that to meaningfully actualize their duty to truth, prosecutors must extricate themselves from their extant close relationships with the police by adopting a deliberately confrontational approach to police witnesses. Moreover, once a case is charged, they must overcome their longstanding reluctance to liberal disclosure by immediately providing defense counsel with all available discovery. Scholars have written about the complicated relationship between prosecutors * Professor, CUNY School of Law. J.D., Duke University School of Law. -

Winter 2002 Volume 21 INSIDE: New York to Mutts: “You’Re Worthless” See Page 3

Winter 2002 Volume 21 INSIDE: New York to Mutts: “You’re Worthless” See Page 3 THE QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER OF THE ANIMAL LEGAL DEFENSE FUND Darwin, Meet Dershowitz Courting legal evolution at Harvard Law ights,” declared Alan Dershowitz, pacing the floor of a lecture hall at Harvard Law School, “grow out of wrongs.” “ It seemed the type of pronounce- Rment Dershowitz, who teaches law at Harvard, might deliver during a typical lecture to one of his classes. But this was no typical lecture, and the Ames Courtroom in Austin Hall bore only a passing resemblance to The Paper Chase. The scene was a first-of-its-kind symposium, “The Evolving Legal Status of Chimpanzees.” And Dershowitz’s featured role signaled how far the idea of legal rights for animals has come since the PHOTO BY NANCY O’BRIEN 1970s, when the fictional Professor Kingsfield did his blustery best to stem the tide of change at Harvard and beyond. Harvard Law School today boasts one of the most active chapters of the Student Animal Legal Defense Fund in the nation. The chapter co-spon- sored the daylong symposium with the Chim- panzee Collaboratory, a consortium of attorneys, scientists and public-policy experts of which sionate to those on whom we impose our rules. Still a “legal thing”— ALDF is a charter member. The symposium was Hence the argument for animal rights.” but for how long? moderated by ALDF President Steve Ann Cham- With his fellow legal scholars Laurence Tribe bers, chair of the Collaboratory’s legal committee (who was scheduled to speak at the symposium, and the primary organizer of the event. -

Council of Conservative Citizens

Council of Conservative Citizens Name: Council of Conservative Citizens Type of Organization: Not-for-profit political Ideologies and Affiliations: Far-right homophobic racist white supremacist white nationalist Place of Origin: Atlanta, Georgia Year of Origin: 1985 Founder(s): Gordon Baum (deceased) Places of Operation: St. Louis, Missouri (headquarters); United States Overview Executive Summary: The Council of Conservative Citizens (CCC) is a U.S. not-for-profit organization with a white supremacist and anti-homosexual agenda. The group bills itself as the “only serious nationwide activist group that sticks up for white rights!”1 The CCC grew out of the anti-integration White Citizens’ Councils, also known as the Citizens Councils of America (CCA), which steadily declined in popularity during the 1970s and 1980s.2 In 1985, workers’ compensation attorney and former CCA Midwest field director Gordon Baum and a group of 30 white men created the CCC in Atlanta, Georgia as a successor organization to the CCA.3 At its height in the 1990s, the CCC included some 15,000 members nationwide. 4 The CCC holds protests, rallies, and other events to advocate a white, Christian, and European America. The CCC believes the U.S. government “must reflect Christian beliefs and values” and mass immigration of “non-European and non-Western people” is endangering the United States’ European character.5 The CCC’s website highlights news and claims to educate about so-called “black-on-white violent crime, and in particular, the seemingly endless incidents involving -

Constructing Campus Conflict, Appendices

Challenging the Right, Advancing Social Justice CONSTRUCTING CAMPUS CONFLICT Antisemitism and Islamophobia on U.S. College Campuses, 2007-2011 2007-2011: Appendices Senior Editor Chip Berlet Managing Editor Debra Cash Associate Editor Maria Planansky Political Research Associates (PRA) is a social justice think tank devoted to supporting movements that are building a more just and inclusive democratic society. We expose movements, institutions, and ideologies that undermine human rights. Copyright ©2014, Political Research Associates Political Research Associates 1310 Broadway, Suite 201 Somerville, MA 02144-1837 www.politicalresearch.org design by rachelle galloway-popotas, owl in a tree CONTENTS SURVEY OF MSA STUDENTS ................................................................................................................. 4 ISLAMO-FACISM AWARENESS WEEK (IFAW) 2007 ......................................................................... 7 TRAUMA AND PREJUDICE ................................................................................................................... 10 ADL AND THE PARK51 CONTROVERSY ......................................................................................... 12 RENE GIRARD AND MIMETIC SCAPEGOATING ............................................................................. 13 BIBLIOGRAPHIES ......................................................................................................................................15 Selected LIST OF INCIDENTS DESCRIBED AS ANTISEMITIC ........................................... -

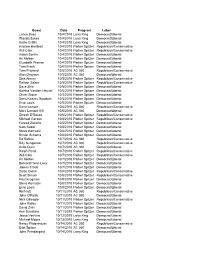

Guest Date Program Label Lance Bass 10/4/2010 Larry King

Guest Date Program Label Lance Bass 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Wanda Sykes 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Kathy Griffin 10/4/2010 Larry King Democrat/Liberal Andrew Breitbart 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Will Cain 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Aaron Sorkin 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Ari Melber 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Elizabeth Warren 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Tom Frank 10/4/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Tom Prichard 10/5/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Alan Grayson 10/5/2010 AC 360 Democrat/Liberal Dick Armey 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Reihan Salam 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Dave Zirin 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Katrina Vanden Heuvel 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Oliver Stone 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Doris Kearns Goodwin 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Errol Louis 10/5/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Dana Loesch 10/6/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Marc Lamont Hill 10/6/2010 AC 360 Democrat/Liberal Dinesh D'Souza 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Michael Gerson 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Republican/Conservative Fareed Zakaria 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Sam Seder 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Steve Kornacki 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Simon Schama 10/6/2010 Parker Spitzer Democrat/Liberal Ed Rollins 10/7/2010 AC 360 Republican/Conservative Billy Nungesser 10/7/2010