Representations and Discourse of Torture in Post 9/11 Television: an Ideological Critique of 24 and Battlestar Galactica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sean Callery

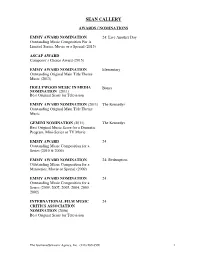

SEAN CALLERY AWARDS / NOMINATIONS EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Live Another Day Outstanding Music Composition For A Limited Series, Movie or a Special (2015) ASCAP AWARD Composer’s Choice Award (2015) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION Elementary Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music (2013) HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA Bones NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score for Television EMMY AWARD NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music GEMINI NOMINATION (2011) The Kennedys Best Original Music Score for a Dramatic Program, Mini-Series or TV Movie EMMY AWARD 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2010 & 2006) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24: Redemption Outstanding Music Composition for a Miniseries, Movie or Special (2009) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION 24 Outstanding Music Composition for a Series (2009, 2007, 2005, 2004, 2003, 2002) INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC 24 CRITICS ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2006) Best Original Score for Television The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 SEAN CALLERY TELEVISION SERIES JESSICA JONES (series) Melissa Rosenberg, Jeph Loeb, exec. prods. ABC / Marvel Entertainment / Tall Girls Melissa Rosenberg, showrunner BONES (series) Barry Josephson, Hart Hanson, Stephen Nathan, Fox / 20 th Century Fox Steve Bees, exec. prods. HOMELAND (pilot & series) Alex Gansa, Howard Gordon, Avi Nir, Gideon Showtime / Fox 21 Raff, Ran Telem, exec. prods. ELEMENTARY (pilot & series) Carl Beverly, Robert Doherty, Sarah Timberman, CBS / Timberman / Beverly Studios Craig Sweeny, exec. prods. MINORITY REPORT (pilot & series) Kevin Falls, Max Borenstein, Darryl Frank, 20 th Century Fox Television / Fox Justin Falvey, exec. prods. Kevin Falls, showrunner MEDIUM (series) Glenn Gordon Caron, Rene Echevarria, Kelsey Paramount TV /CBS Grammer, Ronald Schwary, exec. prods. 24: LIVE ANOTHER DAY (event-series) Kiefer Sutherland, Howard Gordon, Brian 20 TH Century Fox Grazer, Jon Cassar, Evan Katz, Robert Cochran, David Fury, exec. -

Patricia Murray Patricia Clum & Patricia M

PATRICIA MURRAY PATRICIA CLUM & PATRICIA M. MAKE-UP DESIGNER CANADIAN CITIZENSHIP & RESIDENCE / US RESIDENCE / IATSE 891 / ACFC HEAD OF DEPARTMENT FEATURE FILMS DIRECTOR/PRODUCER CAST THE ART OF RACING IN THE RAIN D: Simon Curtis Amanda Seyfried Fox 2000 Pictures P: Joannie Burstein, 2nd Unit Make-up Vancouver Patrick Dempsey, Tania Landau, Make-Up FX Artist Neal H. Moritz THE PACKAGE D: Jake Szymanski Daniel Doheny, Luke Spencer Roberts, Netflix EP: Shawn Williamson, Geraldine Viswanathan, Sadie Calvano, Brightlight Pictures & Jamie Goehring, Kevin Leeson, Eduardo Franco Red Hour Productions Haroon Saleem HOD & Make-Up FX Artist P: Ross Dinerstein, Nicky Weinstock, Ben Stiller, Anders Holm, Kyle Newacheck, Blake Anderson, Adam DeVine STATUS UPDATE D: Scott Speer Ross Lynch, Olivia Holt, Netflix P: Jennifer Gibgot, Dominic Rustam, Harvey Guillen, Famke Janssen, Offspring Entertainment & Adam Shankman, Shawn Williamson Wendi McLendon-Covey Brightlight Pictures HOD TOMORROWLAND D: Brad Bird Raffey Cassidy, Kathryn Hahn Walt Disney Pictures P: Damon Lindelof Make-Up Onset FX Supervisor Co-P: Bernie Bellew, Tom Peitzman PERCY JACKSON: D: Thor Freudenthal Missy Pyle, Yvette Nicole Brown, SEA OF MONSTERS P: Chris Columbus, Christopher Redman Fox 2000 Pictures Karen Rosenfelt, Michael Barnathan Make-Up FX Supervisor DAYDREAM NATION D: Michael Goldbach Personal Make-Up Artist to Kat Dennings Screen Siren Pictures EP: Tim Brown, Cameron Lamb HOD P: Trish Dolman, Christine Haebler, Michael Olsen, Simone Urdl THE TWILIGHT SAGA: ECLIPSE D: David Slade Ashley Greene, Bryce Dallas Howard, Summit Entertainment P: Wyck Godfrey, Greg Mooradian, Kellan Lutz Make-Up Artist Main Unit Karen Rosenfelt SLAP SHOT 2 D: Steve Boyum Stephen Baldwin, Gary Busey, Universal Pictures P: Ron French Callum Keith Rennie, Jessica Steen HOD JUST FRIENDS D: Roger Kumble Ryan Reynolds New Line Cinema P: Chris Bender, Bill Johnson, Make-Up FX Artist Michael Ohoven, J.C. -

Vendor Name Date Type of Payment Check Amount IL State Disbursement Unit 01/02/2015 Paper Check 18.00 Janna L

PLANO INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT ACCOUNTS PAYABLE CHECK REGISTER JANUARY 2015 Vendor Name Date Type of Payment Check Amount IL State Disbursement Unit 01/02/2015 Paper Check 18.00 Janna L. Countryman, Standing Chapter 13 Trustee 01/02/2015 Paper Check 397.50 PHEAA 01/02/2015 Paper Check 128.34 Standing Chapter 13 Trustee, Janna Countryman 01/02/2015 Paper Check 665.50 US Department of Education 01/02/2015 Paper Check 158.77 US Department of Education 01/02/2015 Paper Check 81.97 US Treasury 01/02/2015 Paper Check 50.00 ABECEDARIAN 01/06/2015 Paper Check 18.00 Able Auto & Truck Parts 01/06/2015 Paper Check 237.58 ABLE COMMUNICATIONS 01/06/2015 Paper Check 12,741.66 ABLE ELECTRIC SERVICE INC 01/06/2015 Paper Check 5,779.11 Abuelo's 01/06/2015 Paper Check 500.21 ACCENTO - THE LANGUAGE CO 01/06/2015 Paper Check 220.00 ADVERTISING MATTERS LLC 01/06/2015 Paper Check 802.50 Aerowave Technologies, Inc. 01/06/2015 Paper Check 535.00 Alexander Navarro 01/06/2015 Paper Check 135.00 Alfred Ennels 01/06/2015 Paper Check 75.00 ALL WORLD TRAVEL & TOURS 01/06/2015 Paper Check 23,100.00 ALLAN BURNS 01/06/2015 Paper Check 340.00 ALLEN KLARK 01/06/2015 Paper Check 340.00 Alpha Testing, Inc. 01/06/2015 Paper Check 2,300.00 ALPHONSO WARFIELD 01/06/2015 Paper Check 135.00 AMERICA TEAM SPORTS 01/06/2015 Paper Check 5,613.00 AMERICAN EXPRESS 01/06/2015 Paper Check 11,362.18 AMERICAN TIME & SIGNAL 01/06/2015 Paper Check 181.63 APPLE SPECIALTIES 01/06/2015 Paper Check 145.00 ARPIN AMERICA MOVING SYSTEM 01/06/2015 Paper Check 33,953.00 ARTA TRAVEL 01/06/2015 Paper -

A NATIONAL CONFERENCE Define Justice

RY SA VER ANNI C’S 30th AR FACING RACE A NATIONAL CONFERENCE Define Justice. Make Change. November 15-17, 2012 BALTIMORE HILTON BALTIMORE, MD 30/.3/2%$ "9 4(% !00,)%$ 2%3%!2#( #%.4%2 s !2#/2' THE APPLIED RESEARCH CENTER’S (ARC) MISSION IS TO BUILD AWARENESS, SOLUTIONS, AND LEADERSHIP FOR RACIAL JUSTICE BY GENERATING TRANSFORMATIVE IDEAS, INFORMATION AND EXPERIENCES. ABOUT ARC The Applied Research Center (ARC) is a thirty-year-old, national racial justice organization. ARC envisions a vibrant world in which people of all races create, share and enjoy resources and relationships equitably, unleashing individual potential, embracing collective responsibility and generating global prosperity. We strive to be a leading values-driven social justice enterprise where the culture and commitment created by our multi-racial and diverse staff supports individual and organizational excellence and sustainability. ARC’s mission is to build awareness, solutions and leadership for racial justice by generating transformative ideas, information and experiences. We define racial justice as the systematic fair treatment of people of all races, resulting in equal opportunities and outcomes for all and we work to advance racial justice through media, research, and leadership development. s MEDIA: ARC is the publisher of Colorlines.com, an award-winning, daily news site where race matters. Colorlines brings a critical racial lens and analysis to breaking news stories, as well as in-depth investigations. In 2012, Colorlines’ Shattered Families investigation was awarded the Hillman Prize in Web Journalism and Colorlines partnered with The Nation on the Voting Rights Watch series. In addition to promoting racial justice through our own media, ARC staff is sought after as experts on current race issues, with regular media appearances on MSNBC, NPR, and other national and local broadcast, print, and online outlets. -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

“We Will Make You Regret Everything”

“We will make you Torture in Iran since regret everything” the 2009 elections Freedom from Torture Country Reporting Programme March 2013 Freedom from Torture Country Reporting Programme March 2013 “We will make you regret everything” Torture in Iran since the 2009 elections “Why did this happen to me, what did I do wrong? ...They’ve made me hate my body to a point that I don’t want to shower or get dressed... I feel alone and can’t trust another person.” Case study - Sanaz, page 6 3 Table of Contents Summary and key findings ............................................................. 7 Key findings of the report .................................................................... 8 Recommendations .......................................................................... 10 Introduction ................................................................................... 11 Freedom from Torture’s history of working with Iranian torture survivors 11 Case sample and method ..................................................................... 11 1. Case Profile ............................................................................................ 12 a. Place of origin and place of residence when detained .................................. 12 b. Ethnicity and religious identity .............................................................. 12 c. Ordinary occupation .......................................................................... 13 d. History of activism or dissent .............................................................. -

The Women of Battlestar Galactica and Their Roles : Then and Now

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 The women of Battlestar Galactica and their roles : then and now. Jesseca Schlei Cox 1988- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cox, Jesseca Schlei 1988-, "The women of Battlestar Galactica and their roles : then and now." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 284. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/284 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE WOMEN OF BATTLESTAR GALACTICA AND THEIR ROLES: THEN AND NOW By Jesseca Schleil Cox B.A., Bellarmine University, 2010 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degre:e of Master of Arts Department of Sociology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2013 Copyright 2013 by Jesseca Schlei Cox All Rights Reserved The Women of Battlestar Galactica and Their Roles: Then and Now By Jesseca Schlei Cox B.A., Bellarmine University, 2010 Thesis Approved on April 11, 2013 by the following Thesis Committee: Gul Aldikacti Marshall, Thesis Director Cynthia Negrey Dawn Heinecken ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my mother and grandfather Tracy Wright Fritch and Bill Wright who instilled in me a love of science fiction and a love of questioning the world around me. -

St. John's College Library

ST. JOHN'S COLLEGE LIBRARY 11111111111111111~~mn1mr1m1111111111111113 1696 01138 2247 St. John's College ANNAPOLIS EDITION COMMENCEMENT '97 Ray Cave and Eva Brann in Annapolis ............................................ 8 Nancy Buchenauer in Santa Fe .......... 9 ALUMNI AUTHORS A semi-sci-fi thriller, a war-time tale, and a handbook on Socratic practice-Johnny authors show their versatility........................................... 12 REAL WORK-REAL PLAY The big three spring events-Reality, prank, and croquet-break the year long great books tension and demand real-world skills ................................. 14 DEPARTMENTS From the Bell Towers: Eva Brann retires as dean; a unity resolution; report on the fire in Santa Fe; SJ C says no to rankings ..................................... 2 The Program: Report on the Dean's Statement of Educational Policy................................................ 26 Scholarship: A new translation of the Sophist ............... ·................................. 7 Alumni Association: The North Carolina Chapter; a report from the Treasurer........................................... 18 Alumni Profiles: Fritz Hinrichs conducts a virtual seminar; a Graduate Institute alumna tells her story.......... 10 Campus Life: Behind the scenes in Santa Fe with scholar-gardener Pat McCue and in Annapolis with the print shop .................................................. 24 Letters .............................................. 17 Class Notes ...................................... 20 Remington Kerper and Joseph Manheim are prepared for commencement: they've read the books, they've written the papers, and they've proven themselves on the croquet court. St. John's extracurriculars are not only a recreational release for academically frazzled students, they also demand real-world organizational and planning skills. See story on page 14. Photo by Keith Harvey. From the Bell Towers ... DESCRIBING THE ORBITS OF RESOLUTION THE PLANET BRANN LINKS UNITY, Eva Brann's deanship is celebrated with a party and speeches. -

And Battlestar Galactica (2003)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Saskatchewan's Research Archive Evil, Dangerous, and Just Like Us: Androids and Cylons in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) and Battlestar Galactica (2003) A Project Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Chelsea Catherine Cox © Copyright Chelsea Catherine Cox, September 2011. All Rights Reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this project in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for the copying of this project in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my project work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this project or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my project. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this project in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of English University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada OR Dean College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A2 Canada i ABSTRACT The nature of humanity and what it means to be human has long been the focus of science fiction writers in all media. -

The Death Penalty As Torture

The Death Penalty as Torture bessler DPT last pages.indb 1 1/12/17 11:47 AM Also by John D. Bessler Death in the Dark: Midnight Executions in Amer i ca Kiss of Death: Amer i ca’s Love Affair with the Death Penalty Legacy of Vio lence: Lynch Mobs and Executions in Minnesota Writing for Life: The Craft of Writing for Everyday Living Cruel and Unusual: The American Death Penalty and the Found ers’ Eighth Amendment The Birth of American Law: An Italian Phi los o pher and the American Revolution Against the Death Penalty (editor) bessler DPT last pages.indb 2 1/12/17 11:47 AM The Death Penalty as Torture From the Dark Ages to Abolition John D. Bessler Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina bessler DPT last pages.indb 3 1/12/17 11:47 AM Copyright © 2017 John D. Bessler All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bessler, John D., author. Title: The death penalty as torture : from the dark ages to abolition / John D. Bessler. Description: Durham, North Carolina : Carolina Academic Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016036253 | ISBN 9781611639261 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Capital punishment--History. | Capital punishment--United States. Classification: LCC K5104 .B48 2016 | DDC 345/.0773--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016036253 Carolina Academic Press, LLC 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America bessler DPT last pages.indb 4 1/12/17 11:47 AM For all victims of torture bessler DPT last pages.indb 5 1/12/17 11:47 AM bessler DPT last pages.indb 6 1/12/17 11:47 AM “Can the state, which represents the whole of society and has the duty of protect- ing society, fulfill that duty by lowering itself to the level of the murderer, and treating him as he treated others? The forfeiture of life is too absolute, too irre- versible, for one human being to inflict it on another, even when backed by legal process.” — U.N. -

Inspiring Americans to Greatness Attendees of the 2019 Freedom Conference Raise Their Hands in Solidarity with Hong Kong Pro-Democracy Protesters

Annual Report 2019-20 Inspiring Americans to Greatness Attendees of the 2019 Freedom Conference raise their hands in solidarity with Hong Kong pro-democracy protesters The principles espoused by The Steamboat Institute are: Limited taxation and fiscal responsibility • Limited government • Free market capitalism Individual rights and responsibilities • Strong national defense Contents INTRODUCTION EMERGING LEADERS COUNCIL About the Steamboat Institute 2 Meet Our Emerging Leaders 18 Letter from the Chairman 3 MEDIA COVERAGE AND OUTREACH AND EVENTS PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT Campus Liberty Tour 4 Media Coverage 20 Freedom Conferences and Film Festival 8 Social Media Analytics 21 Additional Outreach 10 FINANCIALS TONY BLANKLEY FELLOWSHIP 2019-20 Revenue & Expenses 22 FOR PUBLIC POLICY & AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM FUNDING About the Tony Blankley Fellowship 11 2019 and 2020 Fellows 12 Funding Sources 23 Past Fellows 14 MEET OUR PEOPLE COURAGE IN EDUCATION AWARD Board of Directors 24 Recipients 16 National Advisory Board 24 Our Team 24 The Steamboat Institute 2019-20 Annual Report – 1 – About The Steamboat Institute Here at the Steamboat Institute, we are Defenders of Freedom When we started The Steamboat Institute in 2008, it was and Advocates of Liberty. We are admirers of the bravery out of genuine concern for the future of our country. We take and rugged individualism that has made this country great. seriously the concept that freedom is never more than one We are admirers of the greatness and wisdom that resides generation away from extinction. in every individual. We understand that this is a great nation because of its people, not because of its government. The Steamboat Institute has succeeded beyond anything Like Thomas Jefferson, we would rather be, “exposed to we could have imagined when we started in 2008. -

Child Care Advisory Council Meeting Minutes April 24, 2018

Child Care Advisory Council Meeting Minutes April 24, 2018 In attendance: Christa Bell, Brenda Bowman, Bill Buchanan Tal Curry, Twylynn Edwards, Kimberly Gipson, Mike Haney, Amy Hood, Holly LaFavers, Patricia Porter, Erica Tipton, and Sandra Woodall. Minutes of previous meeting were presented and reviewed. A nomination was made for approval of minutes and seconded. Approval of minutes was voted upon and passed. Christa Bell reminded current members that membership expires June, 2018. Application to reapply for membership is available online. Christa Bell will send link to all members. Christa Bell discussed the need for a co-chair. Dr. Amy Hood was nominated and accepted nomination. Unanimous approval was given by quorum. Christa Bell then presented Division of Child Care Updates: CCDF State Plan – Draft of State Plan is available on the DCC website at https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dcbs/dcc/Pages/default.aspx and is open for public comment until 05/02/2018. A public hearing is scheduled following the Child Care Advisory Council meeting today. Comments can be emailed to Christa Bell at [email protected]. The state plan serves as the application for Child Care and Development Funds for the next three years. Christa Bell indicated stakeholder engagement and involvement needs to improve with regards to the development and revision of the State Plan. Christa Bell requested members email her with suggestions for membership of the stakeholder group. National Background Check Program – Implementation phase began in March. There are currently fingerprint sites in 80 counties across the state. A KOG account is required to access NBCP.