Incubating Monsters: Prosecutorial Responsibility for the Rampart Scandal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Police Misconduct As a Cause of Wrongful Convictions

POLICE MISCONDUCT AS A CAUSE OF WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS RUSSELL COVEY ABSTRACT This study gathers data from two mass exonerations resulting from major police scandals, one involving the Rampart division of the L.A.P.D., and the other occurring in Tulia, Texas. To date, these cases have received little systematic attention by wrongful convictions scholars. Study of these cases, however, reveals important differences among subgroups of wrongful convictions. Whereas eyewitness misidentification, faulty forensic evidence, jailhouse informants, and false confessions have been identified as the main contributing factors leading to many wrongful convictions, the Rampart and Tulia exonerees were wrongfully convicted almost exclusively as a result of police perjury. In addition, unlike other exonerated persons, actually innocent individuals charged as a result of police wrongdoing in Rampart or Tulia only rarely contested their guilt at trial. As is the case in the justice system generally, the great majority pleaded guilty. Accordingly, these cases stand in sharp contrast to the conventional wrongful conviction story. Study of these groups of wrongful convictions sheds new light on the mechanisms that lead to the conviction of actually innocent individuals. I. INTRODUCTION Police misconduct causes wrongful convictions. Although that fact has long been known, little else occupies this corner of the wrongful convictions universe. When is police misconduct most likely to result in wrongful convictions? How do victims of police misconduct respond to false allegations of wrongdoing or to police lies about the circumstances surrounding an arrest or seizure? How often do victims of police misconduct contest false charges at trial? How often do they resolve charges through plea bargaining? While definitive answers to these questions must await further research, this study seeks to begin the Professor of Law, Georgia State University College of Law. -

The Rampart Scandal

Human Rights Alert, NGO PO Box 526, La Verne, CA 91750 Fax: 323.488.9697; Email: [email protected] Blog: http://human-rights-alert.blogspot.com/ Scribd: http://www.scribd.com/Human_Rights_Alert 10-04-08 DRAFT 2010 UPR: Human Rights Alert (Ngo) - The United States Human Rights Record – Allegations, Conclusions, Recommendations. Executive Summary1 1. Allegations Judges in the United States are prone to racketeering from the bench, with full patronizing by US Department of Justice and FBI. The most notorious displays of such racketeering today are in: a) Deprivation of Liberty - of various groups of FIPs (Falsely Imprisoned Persons), and b) Deprivation of the Right for Property - collusion of the courts with large financial institutions in perpetrating fraud in the courts on homeowners. Consequently, whole regions of the US, and Los Angeles is provided as an example, are managed as if they were extra-constitutional zones, where none of the Human, Constitutional, and Civil Rights are applicable. Fraudulent computers systems, which were installed at the state and US courts in the past couple of decades are key enabling tools for racketeering by the judges. Through such systems they issue orders and judgments that they themselves never consider honest, valid, and effectual, but which are publicly displayed as such. Such systems were installed in violation of the Rule Making Enabling Act. Additionally, denial of Access to Court Records - to inspect and to copy – a First Amendment and a Human Right - is integral to the alleged racketeering at the courts - through concealing from the public court records in such fraudulent computer systems. -

Free Peltier?

Journal of Anti-Racist Action, Research & Education TURNINGVolume 12 Number 3 Fall 1999THE $2/newsstands TIDE In this issue: Puerto Rico*Shut Down the WTO!*ARA Mumia*Exchange on Zionism*Big Mountain*Police Brutality Free Peltier? People Against Racist Terror*PO Box 1055*Culver City 90232 310-288-5003*ISSN 1082-6491*e-mail: <[email protected]> PART'S Perspective: Puerto Rican Political Prisoners and Prisoners of War Released Que Viva Puerto Rico Libre! The forces of liberation and decolonization, and the campaign to free political emerged from prison gates for the first time in as much as 19 years. The campaign prisoners and prisoners of war held by the U.S., have won a tremendous victory. had united even Puerto Ricans who identified with commonwealth and statehood Eleven Puerto Rican political prisoners and prisoners of war were released from U.S. parties behind the demand for freedom for the independentistas. Prior to their release, prisons in September, under a conditional clemency by President Clinton. We must over 100,000 people marched in San Juan to demand that Clinton eliminate the savor the victory, and also deepen our understanding of how it was won and how it unjust and insulting conditions he was placing on their release. can be built on. An ecstatic crowd celebrated the released freedom fighters when they arrived in Edwin Cortes, Elizam Escobar, Ricardo Jimenez, Adolfo Matos, Dylcia Pagan, Puerto Rico. As TTT was going to press, the prisoners were scheduled to appear Alberto Rodriguez, Alicia Rodriguez, Ida Luz Rodriguez, Luis Rosa, Alejandrina together at a rally in Lares on September 23, commemorating the Grito de Lares, the Torres, and Carmen Valentin, were justly welcomed as heroes and patriots by the call for Puerto Rican independence from Spain. -

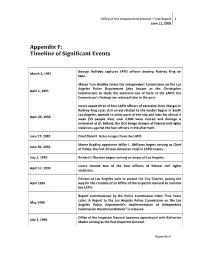

Appendix F: Timeline of Significant Events

Office of the Independent Monitor: Final Report 1 June 11, 2009 Appendix F: Timeline of Significant Events George Holliday captures LAPD officers beating Rodney King on March 2, 1991 tape. Mayor Tom Bradley forms the Independent Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department (also known as the Christopher April 1, 1991 Commission) to study the excessive use of force in the LAPD; the Commission’s findings are released later in the year. Jurors acquit three of four LAPD officers of excessive force charges in Rodney King case; civil unrest related to the verdict begins in South Los Angeles, spreads to other parts of the city and lasts for almost a April 29, 1992 week (55 people died, over 2,000 were injured and damage is estimated at $1 billion); the DOJ brings charges of federal civil rights violations against the four officers in the aftermath. June 27, 1992 Chief Daryl F. Gates resigns from the LAPD. Mayor Bradley appointee Willie L. Williams begins serving as Chief June 30, 1992 of Police, the first African‐American chief in LAPD history. July 1, 1993 Richard J. Riordan begins serving as mayor of Los Angeles. Jurors convict two of the four officers of federal civil rights April 17, 1993 violations. Citizens of Los Angeles vote to amend the City Charter, paving the April 1995 way for the creation of an Office of the Inspector General to monitor the LAPD. Report commissioned by the Police Commission titled “Five Years Later: A Report to the Los Angeles Police Commission on the Los May 1996 Angeles Police Department’s Implementation of Independent Commission Recommendations” is released. -

Screening the LAPD

1 Screening the L.A.P.D.: Cinematic Representations of Policing and Discourses of Law Enforcement in Los Angeles, 1948-2003. by Robert Bevan University College London Ph.D. Thesis 2 Declaration I, Robert Bevan, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Thesis Abstract This thesis examines cinematic representations of the L.A.P.D. within the context of discourses of law enforcement in Los Angeles and contends that these feature films constitute a significant strand within such discourse. This contention, which is based upon the various identifiable ways in which the films engage with contemporary issues, acknowledges that the nature of such engagement is constrained by the need to produce a commercially viable fictional entertainment. In four main chronological segments, I argue that it is also influenced by the increasing ethnic and gendered diversity of film-makers, by their growing freedom to screen even the most sensitive issues and by the changing racial and spatial politics of Los Angeles. In the 1940s and 1950s, the major studios were prepared to illustrate some disputed matters, such as wire-tapping, but represented L.A.P.D. officers as white paragons of virtue and ignored their fractious relationships with minority communities. In the aftermath of the Watts riot of 1965, racial tensions were more difficult to ignore and, under a more liberal censorship regime, film-makers―led by two independent African American directors―began to depict instances of police racism and brutality. -

Rampart Reconsidered Executive Summary

R A M P A R T R e c o n s i d e r e d The Searc h for Real Refo rm Seven Years Later Execut ive Summa r y Blue Ribbon Panel Chair Additional Staff Rampart Review Constance L. Rice Kenneth Berland Jenna Cobb Panel Panel Members John Mathews Jan L. Handzlik Pilar Mendoza Laurie L. Levenson Margaret Middleton Stephen A. Mansfield Natasha Saggar Carol A. Sobel Rishi Sahgal Edgar Hugh Twine Regina Tuohy Panel Members Emeriti Erwin Chemerinsky Andrea Ordin Maurice Suh Executive Director Kathleen Salvaty Lead Investigator Brent A. Braun Additional Investigators Eusebio Benavidez Morris D. Hayes Jack Keller Pete McGuire Michael Wolf Special Hon. James K. Hahn Linder & Associates Merrick Bobb Alan J. Skobin Thanks Rick J. Caruso Michael J. Strumwasser *** Los Angeles Police Gerald Chaleff Richard Tefank Akin Gump Strauss Foundation Warren M. Christopher Karen Wagener Hauer & Feld LLP Los Angeles City Johnnie L. Cochran, Jr. Samuel Walker Personnel Department Hon. Steve Cooley Hon. Jack Weiss Burke, Williams David S. Cunningham III Hon. Debra W. Yang & Sorenson, LLP Technical Threat Hon. Rockard J. Delgadillo Roberta Yang Donna Denning Gregory A. Yates Gibson, Dunn Analysis Group, Inc. Richard E. Drooyan & Crutcher LLP *** Paul Enox All of the dedicated Howrey LLP Shelley Freeman LAPD officers and LAPD Office of the James J. Fyfe employees who gave Lindahl, Schnabel, Inspector General Bonifacio Bonny Garcia their time and insight Kardassakis & Beck LLP Michael J. Gennaco to this Panel in Latin American Law Gigi Gordon order to improve the Nossaman Guthner Enforcement Association Michael P. Judge department. -

Lapd Blues: Scandal

PBS - frontline: l.a.p.d. blues: scandal A chronology of the unfolding events and discoveries of police misconduct which eventually blew up into the Rampart scandal. The scandal was ignited by one L.A.P.D. officer, Rafael Perez, who charged that dozens of his fellow officers regularly were involved in making false arrests, giving perjured testimony and framing innocent people. The Rampart scandal was ignited by the allegations of one man, L.A.P.D. officer Rafael Perez. Here's a profile of Perez and exclusive audio excerpts from his confessions. Perez claimed the Rampart CRASH unit was filled with drug-dealing rogue cops who were shaking down gang members and framing innocent people. But Perez's credibility is now turning out to be a very large question. Here are the views of L.A.P.D. Chief Bernard Parks, Former L.A.P.D.Chief Daryl Gates, Judge Larry Fidler,former L.A. District Attorney Gil Garcetti, and Detective Mike Hohan. Even before Perez's allegations surfaced, the L.A.P.D. was investigating suspicious activity among some officers in the Rampart CRASH unit. However, critics like Detective Russell Poole claim the L.A.P.D. wasn't really interested in getting to the bottom of what was happening. Poole claims crucial leads were ignored in the early stages of the investigation. Others say administrative decisions taken after the scandal surfaced discouraged officers with critical information from coming forward. Here are the views of Detective Poole, L.A.P.D. Chief Bernard Parks, Gerald Chaleff, former president of the L.A. -

Report of the Rampart Independent Review Panel

REPORT OF THE RAMPART INDEPENDENT REVIEW PANEL A report to the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners concerning the operations, policies, and procedures of the Los Angeles Police Department in the wake of the Rampart scandal EXECUTIVE SUMMARY November 16, 2000 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Los Angeles, long home to one of the country's leading police forces, is now struggling to address one of the worst police scandals in American history. At the center of the scandal are allegations of corruption and widespread police abuse by anti-gang officers assigned to the Los Angeles Police Department's Rampart Area. Rampart Area is located just west of downtown Los Angeles, covers 7.9 square miles, and is one of the busiest and largest operational commands within the LAPD, with more than 400 sworn and civilian personnel assigned. The Area has the highest population density in Los Angeles, with approximately 33,790 people per square mile, and the crime rate has always been among the highest in Los Angeles. By the mid-1980’s, the Rampart Area experienced a significant increase in violent street gangs, heavily involved in narcotics trafficking with easy access to weapons. The Los Angeles Police Department responded with a branch of its special anti-gang unit – known as CRASH, "Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums." Determined to cut crime, LAPD gave Rampart CRASH officers wide latitude to aggressively fight gangs. According to the LAPD, gang-related crimes in Rampart Area fell from 1,171 in 1992 to 464 for 1999, a reduction that exceeded the city-wide decline in violent crime over the same period. -

U.S. V. City of Los Angeles

REPORT OF THE RAMPART INDEPENDENT REVIEW PANEL A report to the Los Angeles Board of Police Commissioners concerning the operations, policies, and procedures of the Los Angeles Police Department in the wake of the Rampart scandal EXECUTIVE SUMMARY November 16, 2000 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction Los Angeles, long home to one of the country's leading police forces, is now struggling to address one of the worst police scandals in American history. At the center of the scandal are allegations of corruption and widespread police abuse by anti-gang officers assigned to the Los Angeles Police Department's Rampart Area. Rampart Area is located just west of downtown Los Angeles, covers 7.9 square miles, and is one of the busiest and largest operational commands within the LAPD, with more than 400 sworn and civilian personnel assigned. The Area has the highest population density in Los Angeles, with approximately 33,790 people per square mile, and the crime rate has always been among the highest in Los Angeles. By the mid-1980’s, the Rampart Area experienced a significant increase in violent street gangs, heavily involved in narcotics trafficking with easy access to weapons. The Los Angeles Police Department responded with a branch of its special anti-gang unit – known as CRASH, "Community Resources Against Street Hoodlums." Determined to cut crime, LAPD gave Rampart CRASH officers wide latitude to aggressively fight gangs. According to the LAPD, gang-related crimes in Rampart Area fell from 1,171 in 1992 to 464 for 1999, a reduction that exceeded the city-wide decline in violent crime over the same period. -

One Bad Cop - New York Times

One Bad Cop - New York Times http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B00E1D614... October 1, 2000 One Bad Cop By LOU CANNON The case that would eventually spark the most damaging scandal in the history of the Los Angeles Police Department began early on the afternoon of Nov. 26, 1996, when Javier Francisco Ovando was wheeled on a gurney into a downtown courtroom of the Los Angeles County Hall of Justice for a pretrial hearing. ''He was emaciated, frail, such a little man,'' recalled Tamar Toister, the public defender who was assigned his case, one of seven she would have that day. Ovando was charged with assaulting Rafael Perez and Nino Durden, two Los Angeles police officers, with a semiautomatic weapon. Since the Honduran-born Ovando then spoke no English and the Israeli-born Toister didn't speak Spanish, they conversed through an interpreter. But Ovando could barely talk in any language. A month and a half earlier, on Oct. 12, Perez and Durden, the two officers he was accused of assaulting, had shot him in the neck and chest. Through the interpreter, Ovando softly asserted his innocence and said he did not remember much of what happened except that ''bad cops'' had tried to kill him. No one believed Ovando, who had the number 18 tattooed on the back of his neck, signifying membership in the 18th Street Gang, known in Los Angeles for its narcotics dealings and brutal killings. Nor did anyone in the courtroom except Ovando believe that Perez was a bad cop. To those gathered at the hearing, Perez seemed composed and credible as he told how Ovando, brandishing a Tec-22 semiautomatic pistol, had burst into a darkened fourth-floor room of an abandoned apartment building that he and Durden were using as an observation post to monitor gang activity in the street below. -

Les Figures De Policiers En Eaux Troubles, Symboles D'une

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archive Ouverte en Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication Entre ombres et lumières : les figures de policiers en eaux troubles, symboles d’une Amérique en perte de repères (The Wire, The Shield, Dexter Julien Achemchame To cite this version: Julien Achemchame. Entre ombres et lumières : les figures de policiers en eaux troubles, symboles d’une Amérique en perte de repères (The Wire, The Shield, Dexter. TV/Series, GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures, 2012, Les Séries télévisées américaines contemporaines : entre la fiction, les faits, et le réel, pp.344-359. 10.4000/tvseries.1521. hal-01852797 HAL Id: hal-01852797 https://hal-univ-paris3.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01852797 Submitted on 2 Aug 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. TV/Series 1 | 2012 Les Séries télévisées américaines contemporaines : entre la fiction, les faits, et le réel Entre ombres et lumières : les figures de policiers en eaux troubles, symboles d’une Amérique en perte de repères (The Wire, The Shield, Dexter) Julien Achemchame Éditeur GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Édition électronique URL : http://tvseries.revues.org/1521 DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.1521 ISSN : 2266-0909 Référence électronique Julien Achemchame, « Entre ombres et lumières : les figures de policiers en eaux troubles, symboles d’une Amérique en perte de repères (The Wire, The Shield, Dexter) », TV/Series [En ligne], 1 | 2012, mis en ligne le 15 mai 2012, consulté le 01 octobre 2016. -

BAD COPS; Rafael Perez's Testimony on Police Misconduct Ignited the Biggest Scandal in the History of the L.A.P.D

1 of 1 DOCUMENT The New Yorker May 21, 2001 BAD COPS; Rafael Perez's testimony on police misconduct ignited the biggest scandal in the history of the L.A.P.D. Is it the real story? BYLINE: PETER J. BOYER SECTION: A REPORTER AT LARGE; Pg. 60 LENGTH: 12496 words On September 8, 1999, a thirty-two-year-old Los Angeles police officer named Rafael Perez, who had been caught stealing a million dollars' worth of cocaine from police evidence-storage facilities, signed a plea bargain in which he promised to help uncover corruption within the Los Angeles Police Department. Perez hinted at a scandal that could involve perhaps five other officers, including a sergeant. Later, Perez began to talk about a different magnitude of corruption-wrongdoing that he claimed was endemic to special police units such as the one on which he worked, combatting gangs in the city's dangerous Rampart district. Perez declared that bogus arrests, perjured testimony, and the planting of "drop guns" on unarmed civilians were commonplace. Perez's story unfolded over a period of months, and ignited what came to be known as the Rampart scandal, which the Los Angeles Times called "the worst corruption scandal in L.A.P.D. history." Eventually, Perez implicated about seventy officers in wrongdoing, and the questions he raised about police procedure cast the city's criminal-justice system into a state of tumult. More than a hundred convictions were thrown out, and thousands more are still being investigated. The city attorney's office estimated the potential cost of settling civil suits touched off by the Rampart scandal at a hundred and twenty-five million dollars.