Neoliberal Securityscapes Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Logic of Violence in Civil War Has Much Less to Do with Collective Emotions, Ideologies, Cultures, Or “Greed and Grievance” Than Currently Believed

P1: KAE 0521854091pre CUNY324B/Kalyvas 0 521 85409 1 March 27, 2006 20:2 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: KAE 0521854091pre CUNY324B/Kalyvas 0 521 85409 1 March 27, 2006 20:2 TheLogic of Violence in Civil War By analytically decoupling war and violence, this book explores the causes and dynamics of violence in civil war. Against prevailing views that such violence is either the product of impenetrable madness or a simple way to achieve strategic objectives, the book demonstrates that the logic of violence in civil war has much less to do with collective emotions, ideologies, cultures, or “greed and grievance” than currently believed. Stathis Kalyvas distinguishes between indis- criminate and selective violence and specifies a novel theory of selective violence: it is jointly produced by political actors seeking information and indi- vidual noncombatants trying to avoid the worst but also grabbing what oppor- tunities their predicament affords them. Violence is not a simple reflection of the optimal strategy of its users; its profoundly interactive character defeats sim- ple maximization logics while producing surprising outcomes, such as relative nonviolence in the “frontlines” of civil war. Civil war offers irresistible opportu- nities to those who are not naturally bloodthirsty and abhor direct involvement in violence. The manipulation of political organizations by local actors wishing to harm their rivals signals a process of privatization of political violence rather than the more commonly thought politicization of private life. Seen from this perspective, violence is a process taking place because of human aversion rather than a predisposition toward homicidal violence, which helps explain the para- dox of the explosion of violence in social contexts characterized by high levels of interpersonal contact, exchange, and even trust. -

VITAE Steven D. Levitt Department of Economics University of Chicago 1126 East 59Th Street Chicago, IL 60637 W

VITAE Steven D. Levitt Department of Economics University of Chicago 1126 East 59th Street Chicago, IL 60637 W: (773) 834-1862 F:(773) 702-8490 e-mail:[email protected] PERSONAL Born May 29, 1967 POSITIONS HELD: University of Chicago Department of Economics William Ogden Distinguished Service Professor, July 2008-present Director, Becker Center on Chicago Price Theory, Sept. 2004-present Alvin H. Baum Professor, July 2002-July 2008 Professor, June 1999-June 2002 Associate Professor with tenure, August 1998-May 1999 Assistant Professor, July 1997-July 1998 American Bar Foundation Research fellow, July 1997-present Harvard Society of Fellows Junior Fellow, July 1994-June 1997 Corporate Decisions, Inc. Management Consultant, August 1989-July 1991 EDUCATION: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Ph.D., Economics, 1994 National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship (1992-94) Updated: 9/30/2013 HARVARD UNIVERSITY B.A., Summa Cum Laude, Economics, 1989 Phi Beta Kappa (1989) Young prize for best undergraduate thesis in economics EDITORIAL POSITIONS: Editor, Journal of Political Economy (August 1999-March 2009) Associate Editor, Quarterly Journal of Economics (1998-1999) HONORS, AWARDS, and ACTIVITIES: John Bates Clark Medal, 2003 Garvin Prize (given annually to the most outstanding presentation in the University of California at Berkeley Law and Economics Workshop), 2003 Economic Journal Lecture, Royal Economic Association Meetings, 2003 Fellow, Center for Advanced Study of Behavioral Sciences, Stanford, CA. (In residence, September 2002-May -

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities A Financial System That T OF EN TH M E A Financial System T T R R A E P A E S That Creates Economic Opportunities D U R E Y H T Nonbank Financials, Fintech, 1789 and Innovation Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation Nonbank Financials, Fintech, TREASURY JULY 2018 2018-04417 (Rev. 1) • Department of the Treasury • Departmental Offices • www.treasury.gov U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation Report to President Donald J. Trump Executive Order 13772 on Core Principles for Regulating the United States Financial System Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary Craig S. Phillips Counselor to the Secretary T OF EN TH M E T T R R A E P A E S D U R E Y H T 1789 Staff Acknowledgments Secretary Mnuchin and Counselor Phillips would like to thank Treasury staff members for their contributions to this report. The staff’s work on the report was led by Jessica Renier and W. Moses Kim, and included contributions from Chloe Cabot, Dan Dorman, Alexan- dra Friedman, Eric Froman, Dan Greenland, Gerry Hughes, Alexander Jackson, Danielle Johnson-Kutch, Ben Lachmann, Natalia Li, Daniel McCarty, John McGrail, Amyn Moolji, Brian Morgenstern, Daren Small-Moyers, Mark Nelson, Peter Nickoloff, Bimal Patel, Brian Peretti, Scott Rembrandt, Ed Roback, Ranya Rotolo, Jared Sawyer, Steven Seitz, Brian Smith, Mark Uyeda, Anne Wallwork, and Christopher Weaver. ii A Financial System That Creates Economic -

The Wire: a Comprehensive List of Resources

The Wire: A comprehensive list of resources Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 2 W: Academic Work on The Wire........................................................................................... 3 G: General Academic Work ................................................................................................... 9 I: Wire Related Internet Sources .......................................................................................... 11 1 Introduction William Julius Wilson has argued that: "The Wire’s exploration of sociological themes is truly exceptional. Indeed I do not hesitate to say that it has done more to enhance our understandings of the challenges of urban life and urban inequality than any other media event or scholarly publication, including studies by social scientists…The Wire develops morally complex characters on each side of the law, and with its scrupulous exploration of the inner workings of various institutions, including drug-dealing gangs, the police, politicians, unions, public schools, and the print media, viewers become aware that individuals’ decisions and behaviour are often shaped by - and indeed limited by - social, political, and economic forces beyond their control". Professor William Julius Wilson, Harvard University Seminar about The Wire, 4th April 2008. We have been running courses which examine this claim by comparing and contrasting this fictional representation of urban America -

Police Misconduct As a Cause of Wrongful Convictions

POLICE MISCONDUCT AS A CAUSE OF WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS RUSSELL COVEY ABSTRACT This study gathers data from two mass exonerations resulting from major police scandals, one involving the Rampart division of the L.A.P.D., and the other occurring in Tulia, Texas. To date, these cases have received little systematic attention by wrongful convictions scholars. Study of these cases, however, reveals important differences among subgroups of wrongful convictions. Whereas eyewitness misidentification, faulty forensic evidence, jailhouse informants, and false confessions have been identified as the main contributing factors leading to many wrongful convictions, the Rampart and Tulia exonerees were wrongfully convicted almost exclusively as a result of police perjury. In addition, unlike other exonerated persons, actually innocent individuals charged as a result of police wrongdoing in Rampart or Tulia only rarely contested their guilt at trial. As is the case in the justice system generally, the great majority pleaded guilty. Accordingly, these cases stand in sharp contrast to the conventional wrongful conviction story. Study of these groups of wrongful convictions sheds new light on the mechanisms that lead to the conviction of actually innocent individuals. I. INTRODUCTION Police misconduct causes wrongful convictions. Although that fact has long been known, little else occupies this corner of the wrongful convictions universe. When is police misconduct most likely to result in wrongful convictions? How do victims of police misconduct respond to false allegations of wrongdoing or to police lies about the circumstances surrounding an arrest or seizure? How often do victims of police misconduct contest false charges at trial? How often do they resolve charges through plea bargaining? While definitive answers to these questions must await further research, this study seeks to begin the Professor of Law, Georgia State University College of Law. -

Cuban and Salvadoran Exiles: Differential Cold War–Era U.S

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive DSpace Repository Theses and Dissertations 1. Thesis and Dissertation Collection, all items 2018-06 CUBAN AND SALVADORAN EXILES: DIFFERENTIAL COLD WAR–ERA U.S. POLICY IMPACTS ON THEIR SECOND-GENERATIONS' ASSIMILATION Nazzall, Amal Monterey, CA; Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/59562 Downloaded from NPS Archive: Calhoun NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS CUBAN AND SALVADORAN EXILES: DIFFERENTIAL COLD WAR–ERA U.S. POLICY IMPACTS ON THEIR SECOND-GENERATIONS’ ASSIMILATION by Amal Nazzall June 2018 Thesis Advisor: Tristan J. Mabry Second Reader: Christopher N. Darnton Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Form Approved OMB REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED (Leave blank) June 2018 Master's thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS CUBAN AND SALVADORAN EXILES: DIFFERENTIAL COLD WAR–ERA U.S. POLICY IMPACTS ON THEIR SECOND-GENERATIONS’ ASSIMILATION 6. AUTHOR(S) Amal Nazzall 7. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

“La Lucha Libre Mexicana. Su Función Compensatoria En Relación Al Trauma Cultural”

Traducción del artículo “Mexican Wrestling. Its Compensatory Function in Relation to Cultural Trauma”, del Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche, vol. 4, núm. 4. Con la autorización de UCPress para reproducirse en una página web institucional. “La lucha libre mexicana. Su función compensatoria en relación al trauma cultural” VÍCTOR MANUEL LÓPEZ G. La lucha libre mexicana se deriva del catch-as-catch-can francés de los años 30, que combina la lucha grecorromana con el wrestling estadounidense. Originalmente relacionado con el pancracio1, esta forma de lucha ha trascendido fronteras. La lucha libre ha dado el salto de los cuadriláteros a las páginas de las revistas deportivas, la televisión, el cine y las fotonovelas, consagrando un subgénero cuyos protagonistas se han convertido en héroes icónicos, tal como lo demuestra el siguiente extracto tomado de una narración, transmitida por televisión mexicana en septiembre de 2008. Anunciador: la pelea será a dos de tres caídas sin límite de tiempo. En la esquina de los técnicos tenemos al Dr. Planeta, y en la de los rudos, al Sr. Calavera. ¡Y comienza la pelea! Calavera lanza una patada voladora a su oponente, quien se retuerce de dolor. Calavera inmoviliza a su rival contra el suelo y le mete el dedo en el ojo. Esta es una estratagema ilegal. Público: ¡Auch! ¡Tramposo! ¡Castíguenlo! ¡Llamen a la policía! (Chiflidos e insultos dirigidos al Sr. Calavera.) Anunciador: Planeta huye de la golpiza. Se para y corre hacia las cuerdas. Calavera lo persigue y lanza otro golpe ilegal contra Planeta, que lo evade. Frustra a Calavera usando un candado de cangrejo. -

Police Abuse and Misconduct Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender People in the U.S

United States of America Stonewalled : Police abuse and misconduct against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people in the U.S. 1. Introduction In August 2002, Kelly McAllister, a white transgender woman, was arrested in Sacramento, California. Sacramento County Sheriff’s deputies ordered McAllister from her truck and when she refused, she was pulled from the truck and thrown to the ground. Then, the deputies allegedly began beating her. McAllister reports that the deputies pepper-sprayed her, hog-tied her with handcuffs on her wrists and ankles, and dragged her across the hot pavement. Still hog-tied, McAllister was then placed in the back seat of the Sheriff’s patrol car. McAllister made multiple requests to use the restroom, which deputies refused, responding by stating, “That’s why we have the plastic seats in the back of the police car.” McAllister was left in the back seat until she defecated in her clothing. While being held in detention at the Sacramento County Main Jail, officers placed McAllister in a bare basement holding cell. When McAllister complained about the freezing conditions, guards reportedly threatened to strip her naked and strap her into the “restraint chair”1 as a punitive measure. Later, guards placed McAllister in a cell with a male inmate. McAllister reports that he repeatedly struck, choked and bit her, and proceeded to rape her. McAllister sought medical treatment for injuries received from the rape, including a bleeding anus. After a medical examination, she was transported back to the main jail where she was again reportedly subjected to threats of further attacks by male inmates and taunted by the Sheriff’s staff with accusations that she enjoyed being the victim of a sexual assault.2 Reportedly, McAllister attempted to commit suicide twice. -

Arena Puebla

Octubre 2020 Spanish Reader ARENA PUEBLA Arena Puebla lugar de diversión y tradición. Septiembre es uno de los meses más importantes para los mexicanos, no solo por las fiestas patrias sino también por el “Día Nacional de la Lucha Libre y del Luchador Profesional Mexicano'' que se celebra cada 21 de septiembre. Por esa razón es necesario hablar de la emblemática Arena Puebla, el lugar sagrado para los luchadores, el lugar en donde se desarrollan espectáculos tan emocionantes para los mexicanos. La Arena Puebla se fundó el 18 de julio de 1953, está ubicada en la 13 oriente 402 en el popular barrio El Carmen y tiene un espacio para 3000 aficionados. Fue inaugurada por Salvador Lutteroth González conocido como el padre de la lucha libre mexicana y quien fue el fundador del Consejo Mundial de la Lucha Libre (CMLL). Además, este espacio funciona como escuela de lucha libre, con más de 20 años de experiencia. Este año celebró 67 años de su creación, pero debido a la pandemia los festejos tuvieron que ser postergados. 01 Spanish Institute of Puebla www.sipuebla.com Octubre 2020 En su inauguración, la lucha estelar tuvo a grandes figuras como Black Shadow, Tarzán López, y Enrique Yañez, enfrentando al Verdugo, el Cavernario Galindo y el famosísimo Santo “El Enmascarado de Plata”, quien en aquel momento era el campeón mundial Welter. Diferentes luchadores han engalanado las noches en el cuadrilátero, entre ellos están Blue Demon, El Huracán Ramírez, Arturo Casco “La Fiera”, El Perro Aguayo, Semi- narista, Califa, Danger, El Hércules Poblano, Gorila Osorio, Petronio Limón, El Jabato, Manuel Robles, Furia Chicana, Gardenia Davis, El Faraón, Enrique Vera, Príncipe Rojo, Tarahumara, Chico Madrid, Gavilán, Sombra Poblana, Murciélago, El Santo Poblano, El Perro Aguayo Jr. -

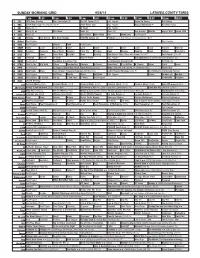

Sunday Morning Grid 9/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Tunnel to Towers Bull Riding 4 NBC 2014 Ryder Cup Final Day. (4) (N) Å 2014 Ryder Cup Paid Program Access Hollywood Å Red Bull Series 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild Exped. Wild 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Green Bay Packers at Chicago Bears. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program The Specialist ›› (1994) Sylvester Stallone. (R) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) La Arrolladora Banda Limón Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue (2012) Baby’s Day Out ›› (1994) Joe Mantegna. -

The Rampart Scandal

Human Rights Alert, NGO PO Box 526, La Verne, CA 91750 Fax: 323.488.9697; Email: [email protected] Blog: http://human-rights-alert.blogspot.com/ Scribd: http://www.scribd.com/Human_Rights_Alert 10-04-08 DRAFT 2010 UPR: Human Rights Alert (Ngo) - The United States Human Rights Record – Allegations, Conclusions, Recommendations. Executive Summary1 1. Allegations Judges in the United States are prone to racketeering from the bench, with full patronizing by US Department of Justice and FBI. The most notorious displays of such racketeering today are in: a) Deprivation of Liberty - of various groups of FIPs (Falsely Imprisoned Persons), and b) Deprivation of the Right for Property - collusion of the courts with large financial institutions in perpetrating fraud in the courts on homeowners. Consequently, whole regions of the US, and Los Angeles is provided as an example, are managed as if they were extra-constitutional zones, where none of the Human, Constitutional, and Civil Rights are applicable. Fraudulent computers systems, which were installed at the state and US courts in the past couple of decades are key enabling tools for racketeering by the judges. Through such systems they issue orders and judgments that they themselves never consider honest, valid, and effectual, but which are publicly displayed as such. Such systems were installed in violation of the Rule Making Enabling Act. Additionally, denial of Access to Court Records - to inspect and to copy – a First Amendment and a Human Right - is integral to the alleged racketeering at the courts - through concealing from the public court records in such fraudulent computer systems.