Testing Freedom of Information in Liberia a Scoping Paper on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia

‘Listen, Politics is not for Children:’ Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Henryatta Louise Ballah Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Drs. Ousman Kobo, Advisor Antoinette Errante Ahmad Sikianga i Copyright by Henryatta Louise Ballah 2012 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the historical causes of the Liberian civil war (1989- 2003), with a keen attention to the history of Liberian youth, since the beginning of the Republic in 1847. I carefully analyzed youth engagements in social and political change throughout the country’s history, including the ways by which the civil war impacted the youth and inspired them to create new social and economic spaces for themselves. As will be demonstrated in various chapters, despite their marginalization by the state, the youth have played a crucial role in the quest for democratization in the country, especially since the 1960s. I place my analysis of the youth in deep societal structures related to Liberia’s colonial past and neo-colonial status, as well as the impact of external factors, such as the financial and military support the regime of Samuel Doe received from the United States during the cold war and the influence of other African nations. I emphasize that the socio-economic and political policies implemented by the Americo- Liberians (freed slaves from the U.S.) who settled in the country beginning in 1822, helped lay the foundation for the civil war. -

Irregular Warfare and Liberia's First Civil

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AND AREA STUDIES 57 Volume 11, Number 1, 2004, pp.57-77 Irregular Warfare and Liberia’s First Civil War George Klay Kieh, Jr. The article examines the causes of the irregular war in Liberia from 1989-1997, the forces and dynamics that shaped the war, the impact of the war on state collapse and the prospects for conflict resolution and peace-building. The findings show that the war was caused by a confluence of factors. Several warlordist militias were the belligerents in the war. The war and its associated violence precipitated the actual collapse of the Liberian State. Finally, the success of the peace-building project would be dependent upon addressing the causes that occasioned the irregular war. Keywords: Regular warfare, irregular warfare, state collapse, conflict resolution, peace-building, Liberia 1. INTRODUCTION Irregular warfare and its consequent precipitous impact on state collapse has been an enduring feature of human affairs. Even long before the inception of the Westphalian state system in the mid-seventeenth century, various state formations in Africa, the Americas, Asia and Europe emerged, and then collapsed. The precipitants ranged from internal imperatives triggered by issues such as the distribution of societal resources and territory, to the external imperialist impulse. In the case of Africa, during the pre-colonial era, several polities emerged, and then collapsed as a consequence of myriad internal and external factors. During the first two decades of the post-colonial era, irregular warfare in African states was minimized by the regulatory dynamics of the “Cold War.” However, since the end of the “Cold War,” the incidence of irregular warfare, especially its capacity to precipitate state collapse, has accelerated. -

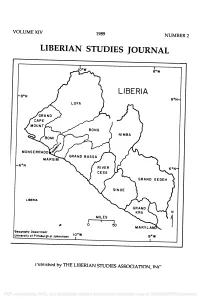

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL r 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 8oW 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY ON APRIL 1980: SOME REFLECTIONS 1 by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF AGRICULTURE AMONG THE KPELLE: KPELLE FARMING THROUGH KPELLE EYES 23 by John Gay "PACIFICATION" UNDER PRESSURE: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERIAN INTERVENTION IN NIMBA 1912 -1918 ............ 44 by Martin Ford BLACK, CHRISTIAN REPUBLICANS: DELEGATES TO THE 1847 LIBERIAN CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION ........................ 64 by Carl Patrick Burrowes TRIBE AND CHIEFDOM ON THE WINDWARD COAST 90 by Warren L. -

Liberia October 2003

Liberia, Country Information Page 1 of 23 LIBERIA COUNTRY REPORT OCTOBER 2003 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT l Scope of the document ll Geography lll Economy lV History V State Structures Vla Human Rights Issues Vlb Human Rights - Specific Groups Vlc Human Rights - Other Issues Annex A - Chronology Annex B - Political Organisations Annex C - Prominent People Annex D - References to Source Material 1. Scope of Document 1.1 This report has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The report has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The report is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the report on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. Geography 2.1 The Republic of Liberia is a coastal West African state of approximately 97,754 sq kms, bordered by Sierra Leone to the west, Republic of Guinea to the north and Côte d'Ivoire to the east. -

Yusador S. Gaye, CPA, CGMA Auditor General, R. L

Management Letter On the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Financial Statements For the Fiscal period ended June 30, 2016 Yusador S. Gaye, CPA, CGMA Auditor General, R. L. Monrovia, Liberia April 2019 Management Letter On the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Financial Statement For the Fiscal period ended June 30, 2016 Table of Contents 1 DETAILED FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................6 1.1 Financial Issues ....................................................................................................6 1.1.1 Discrepancy in Financial Reporting ............................................................................. 6 1.1.2 Expenditure without Supporting Documents ............................................................. 7 1.1.3 Unusual Transaction .................................................................................................... 8 1.1.4 Procurement of Land ..................................................................................................11 1.1.5 Consultancy Contracts ................................................................................................13 1.1.6 Air tickets .....................................................................................................................14 1.1.7 Amendment to the Restated Biometric Passport Contract ......................................15 1.1.8 Payments made outside the Foreign Missions Project’s Scope ...............................16 1.1.9 Un-authorized Payment Vouchers .............................................................................17 -

List of Delegations to the Seventieth Session of the General Assembly

UNITED NATIONS ST /SG/SER.C/L.624 _____________________________________________________________________________ Secretariat Distr.: Limited 18 December 2015 PROTOCOL AND LIAISON SERVICE LIST OF DELEGATIONS TO THE SEVENTIETH SESSION OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY I. MEMBER STATES Page Page Afghanistan......................................................................... 5 Chile ................................................................................. 47 Albania ............................................................................... 6 China ................................................................................ 49 Algeria ................................................................................ 7 Colombia .......................................................................... 50 Andorra ............................................................................... 8 Comoros ........................................................................... 51 Angola ................................................................................ 9 Congo ............................................................................... 52 Antigua and Barbuda ........................................................ 11 Costa Rica ........................................................................ 53 Argentina .......................................................................... 12 Côte d’Ivoire .................................................................... 54 Armenia ........................................................................... -

The Liberian Crisis: Lessons for Intra-State Conflict Management and Prevention in Africa

The Liberian Crisis: Lessons for Intra-State Conflict Management and Prevention in Africa The Liberian Crisis: Lessons for Intra-State Conflict Management and Prevention in Africa Mike Oquaye Working Paper No. 19 June 2001 Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution George Mason University Aboutthe Author Professor Aaron Michael (Mike) Oquaye had a distinguished legal career before entering academe. Having been awarded a B.A. (Hons) in Political Science from the University ofGhanain 1967,hewenton tostudy law at theUniversity ofLondon, gaining bothan Honours Ll.B. anda B.L. there, before becoming a barrister at Lincolns Inn and practicing in both the HighCourt in England and later theSuperior courts of Ghana. In 1984 he began teaching in the department of Political Science at his old University ofGhana at Legon andeight years later was awarded his doctoral degree from thatuniversity, following this withpostdoctoral study at the School of Oriental andAfrican Studies of the University of London. Since that timehe has been a leading figure in thedevelopment of political studies in Ghana,helping to develop newcurricula and postgraduate work in that field. Until recendy, MikeOquayes ownworkhasfocused on the politics of hisowncountryand ofAfrica, and heiswell known asan expert on the establishment and consequences of military rule, as well as the links be tween military rule, local (district) level politics, andvarious forms ofdevel opment. He has written extensively on these subjects and his articles have appeared inAfrica Affairs, Human -

Africa and Liberia in World Politics

© COPYRIGHT by Chandra Dunn 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED AFRICA AND LIBERIA IN WORLD POLITICS BY Chandra Dunn ABSTRACT This dissertation analyzes Liberia’s puzzling shift from a reflexive allegiance to the United States (US) to a more autonomous, anti-colonial, and Africanist foreign policy during the early years of the Tolbert administration (1971-1975) with a focus on the role played by public rhetoric in shaping conceptions of the world which engendered the new policy. For the overarching purpose of understanding the Tolbert-era foreign-policy actions, this study traces the use of the discursive resources Africa and Liberia in three foreign policy debates: 1) the Hinterland Policy (1900-05), 2) the creation of the Organization for African Unity (OAU) (1957- 1963), and finally, 3) the Tolbert administration’s autonomous, anti-colonial foreign policy (1971-1975). The specifications of Liberia and Africa in the earlier debates are available for use in subsequent debates and ultimately play a role in the adoption of the more autonomous and anti-colonial foreign policy. Special attention is given to the legitimation process, that is, the regular and repeated way in which justifications are given for pursuing policy actions, in public discourse in the United States, Europe, Africa, and Liberia. The analysis highlights how political opponents’ justificatory arguments and rhetorical deployments drew on publicly available powerful discursive resources and in doing so attempted to define Liberia often in relation to Africa to allow for certain courses of action while prohibiting others. Political actors claimed Liberia’s membership to the purported supranational cultural community of Africa. -

Information As of 20 March 2017 Has Been Used in Preparation of This Directory

Information as of 20 March 2017 has been used in preparation of this directory. PREFACE The Central Intelligence Agency publishes and updates the online directory of Chiefs of State and Cabinet Members of Foreign Governments weekly. The directory is intended to be used primarily as a reference aid and includes as many governments of the world as is considered practical, some of them not officially recognized by the United States. Regimes with which the United States has no diplomatic exchanges are indicated by the initials NDE. Governments are listed in alphabetical order according to the most commonly used version of each country's name. The spelling of the personal names in this directory follows transliteration systems generally agreed upon by US Government agencies, except in the cases in which officials have stated a preference for alternate spellings of their names. NOTE: Although the head of the central bank is listed for each country, in most cases he or she is not a Cabinet member. Ambassadors to the United States and Permanent Representatives to the UN, New York, have also been included. Key To Abbreviations Adm. Admiral Admin. Administrative, Administration Asst. Assistant Brig. Brigadier Capt. Captain Cdr. Commander Cdte. Comandante Chmn. Chairman, Chairwoman Col. Colonel Ctte. Committee Del. Delegate Dep. Deputy Dept. Department Dir. Director Div. Division Dr. Doctor Eng. Engineer Fd. Mar. Field Marshal Fed. Federal Gen. General Govt. Government Intl. International Lt. Lieutenant Maj. Major Mar. Marshal Mbr. Member Min. Minister, Ministry NDE No Diplomatic Exchange Org. Organization Pres. President Prof. Professor RAdm. Rear Admiral Ret. Retired Sec. Secretary VAdm. -

Post-Emancipation Barbadian Emigrants in Pursuit Of

“MORE AUSPICIOUS SHORES”: POST-EMANCIPATION BARBADIAN EMIGRANTS IN PURSUIT OF FREEDOM, CITIZENSHIP, AND NATIONHOOD IN LIBERIA, 1834 – 1912 By Caree A. Banton Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY August, 2013 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Richard Blackett Professor Jane Landers Professor Moses Ochonu Professor Jemima Pierre To all those who labored for my learning, especially my parents. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to more people than there is space available for adequate acknowledgement. I would like to thank Vanderbilt University, the Albert Gordon Foundation, the Rotary International, and the Andrew Mellon Foundation for all of their support that facilitated the research and work necessary to complete this project. My appreciation also goes to my supervisor, Professor Richard Blackett for the time he spent in directing, guiding, reading, editing my work. At times, it tested his patience, sanity, and will to live. But he persevered. I thank him for his words of caution, advice and for being a role model through his research and scholarship. His generosity and kind spirit has not only shaped my academic pursuits but also my life outside the walls of the academy. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to the members of my dissertation committee: Jane Landers, Moses Ochonu, and Jemima Pierre. They have provided advice and support above and beyond what was required of them. I am truly grateful not only for all their services rendered but also the kind words and warm smiles with which they have always greeted me. -

The Open Door Policy of Liberia

VEROFFENTLICHUNGEN AUS DEM UBERSEE-MUSEUM BREMEN Reihe F Bremer Afrika Archiv Band 17/2 Bremen 1983 Im Selbstverlag des Museums The Open Door Policy of Liberia An Economic History of Modern Liberia R R M. van der Kraaij CONTENTS VOLUME II List of Annexes ii Footnotes 4-61 Introduction 4-61 Chapter 1 . .4-62 Chapter 2 ........ .4-65 Chapter 3 ........ .4-72 Chapter 4- ........ .4-78 Chapter 5 .4-83 Chapter 6 . .4-86 Chapter 7 492 Chapter 8 500 Chapter 9 ........ .509 Chapter 10 ........ .513 Chapter 11 '. .518 Chapter 12 ........ .522 Chapter 13 .528 Annexes 531 Bibliography 662 Curriculum Vitae 703 Index 704. ii LIST OF ANNEXES Page 1 One of the gaps in Liberian History: President Roye's death and his succession 531 2 The Open Door: The question of immigration 533 3 Statement of the public debt 1914-1926 536 4 Public Debt as at August 31, 1926 537 5 Letter dated July 12, 1971 from L. Kwia Johnson, Acting Secretary of the Treasury to A.G. Lund, President, Firestone Plantations Company 538 6 Letter dated October 7, 1969 from W. Edward Greaves, Under Secretary for Revenues to R.F. Dempster, Comptroller, Firestone Plantations Company 539 7 The Planting Agreement of 1926 with amendments of 1935", 1936, 1937, 1939, 1950, 1951, 1953, 1959, 1962 and 1965. 540 8 Summary Table of renegotiation of the 1926 Planting Agreement with Firestone 1974 - 1975 - 1976 551 9 A comparison of four gold and/or diamond mining concession agreements 567 10 The "Columbia Southern Chemical Corporation" concession agreement (1956) and the "Liberian Beach Sands Exploitation Company" mining con- cession agreement (1973). -

Implementation of Abuja II Accord and Post-Conflict Security in Liberia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2007-06 Implementation of Abuja II accord and post-conflict security in Liberia Ikomi, Emmanuel Oritsejolomi Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3440 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS IMPLEMENTATION OF ABUJA II ACCORD AND POST- CONFLICT SECURITY IN LIBERIA by Emmanuel Oritsejolomi Ikomi June 2007 Thesis Advisor: Letitia Lawson Second Reader: Karen Guttieri Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2007 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Implementation of Abuja II Accord and Post- 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Conflict Security in Liberia 6. AUTHOR Emmanuel Oritsejolomi Ikomi 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8.