Plaintiffs Motion to Proceed Anonymously and Declarations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Commentary on the Meaning

A COMMENTARY ON THE MEANING OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA David C. Williams Jallah A. Barbu April 1, 2009 DEDICATION For the People of Liberia TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION PART I: THE TRIPARTITE SYSTEM OF GOVERNMENT CHAPTER ONE: THE GENERAL NATURE OF THE SEPARATION OF POWERS SUBPART I(A): THE JUDICIAL BRANCH CHAPTER TWO: THE JUDICIAL POWER OF THE JUDICIAL BRANCH CH. TWO(a): The POWER TO DECIDE CASES CH. TWO(b): THE POWER TO ENFORCE JUDICIAL MANDATES Ch. Two(b)(1): Presidential Immunity from Court Process Ch. Two(b)(2): The Exclusive Power of the Executive to Enforce the Law Ch. Two(b)(3): The Differences Between the Two Rationales for the Court’s Inability to Order the President to Enforce Its Mandates CH. TWO(c): THE EXCLUSION OF OTHER BRANCHES FROM JUDICIAL FUNCTIONS Ch. Two(c)(1): The Exclusion of the Other Branches from Deciding Cases Ch. Two(c)(1)(i): The Exclusion of the Legislature from Deciding Cases Ch. Two(c)(1)(ii): The Exclusion of the Executive from Deciding Cases Ch. Two(c)(1)(iii): The Limited Power of Executive Agencies to Decide Cases Ch. Two(c)(2): Prohibition on Attempts by the Other Branches to Interfere with the Supreme Court CH. TWO(d): THE POWER TO INTERPRET STATUTES Ch. Two(d)(1): The Power to Determine the Intent of the Legislature But Not to Legislate Ch. Two(d)(2): Prohibition on Interpreting Statutes According to the Court’s Own Policy Views i Ch. Two(d)(3): The Importance of the Words of the Statute in Determining Legislative Intent Ch. -

Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia

‘Listen, Politics is not for Children:’ Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Henryatta Louise Ballah Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Drs. Ousman Kobo, Advisor Antoinette Errante Ahmad Sikianga i Copyright by Henryatta Louise Ballah 2012 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the historical causes of the Liberian civil war (1989- 2003), with a keen attention to the history of Liberian youth, since the beginning of the Republic in 1847. I carefully analyzed youth engagements in social and political change throughout the country’s history, including the ways by which the civil war impacted the youth and inspired them to create new social and economic spaces for themselves. As will be demonstrated in various chapters, despite their marginalization by the state, the youth have played a crucial role in the quest for democratization in the country, especially since the 1960s. I place my analysis of the youth in deep societal structures related to Liberia’s colonial past and neo-colonial status, as well as the impact of external factors, such as the financial and military support the regime of Samuel Doe received from the United States during the cold war and the influence of other African nations. I emphasize that the socio-economic and political policies implemented by the Americo- Liberians (freed slaves from the U.S.) who settled in the country beginning in 1822, helped lay the foundation for the civil war. -

Irregular Warfare and Liberia's First Civil

JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL AND AREA STUDIES 57 Volume 11, Number 1, 2004, pp.57-77 Irregular Warfare and Liberia’s First Civil War George Klay Kieh, Jr. The article examines the causes of the irregular war in Liberia from 1989-1997, the forces and dynamics that shaped the war, the impact of the war on state collapse and the prospects for conflict resolution and peace-building. The findings show that the war was caused by a confluence of factors. Several warlordist militias were the belligerents in the war. The war and its associated violence precipitated the actual collapse of the Liberian State. Finally, the success of the peace-building project would be dependent upon addressing the causes that occasioned the irregular war. Keywords: Regular warfare, irregular warfare, state collapse, conflict resolution, peace-building, Liberia 1. INTRODUCTION Irregular warfare and its consequent precipitous impact on state collapse has been an enduring feature of human affairs. Even long before the inception of the Westphalian state system in the mid-seventeenth century, various state formations in Africa, the Americas, Asia and Europe emerged, and then collapsed. The precipitants ranged from internal imperatives triggered by issues such as the distribution of societal resources and territory, to the external imperialist impulse. In the case of Africa, during the pre-colonial era, several polities emerged, and then collapsed as a consequence of myriad internal and external factors. During the first two decades of the post-colonial era, irregular warfare in African states was minimized by the regulatory dynamics of the “Cold War.” However, since the end of the “Cold War,” the incidence of irregular warfare, especially its capacity to precipitate state collapse, has accelerated. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

UN FOCUS June - August 2011

Vol. 7, No. 04 UN FOCUS June - August 2011 Liberia Goes to the Polls Women Demand More Participation Code of Conduct to Reduce Political Wrangling Message from the Special Representative of the Secretary-General s Liberia stands ready the future direction of the country; to go back to the polls and it is heartening to note that 49% to elect its second post- of all registered voters are women, conflict democratic gov- showing great interest from Liberian ernment, the country women to make their voices heard. Awill hopefully once again proudly The 2011 national elections are declare that democracy, and peace, wholly run by Liberians, unlike in are here to stay. 2005. The United Nations has been A national referendum was suc- engaged with the NEC, but only to cessfully held on 23 August, dem- help coordinate international assist- onstrating the National Elections ance, fill logistic gaps, and to ensure Commission’s increasing capabil- dialogue between the NEC and po- ity to conduct a national event of litical parties to foment agreement grand magnitude, but also that the on the process. Liberian people respect the demo- Elections are always a challenging cratic process. Referendum Day was exercise in any country, but by up- peaceful, and although not all politi- holding the nation’s interest above cal parties were in agreement with personal ambitions and adhering to the holding of the referendum, the the rule of law, political parties and people expressed their will through candidates play a major part in en- the vote, or even through the deci- suring a peaceful process. -

Liberia October 2003

Liberia, Country Information Page 1 of 23 LIBERIA COUNTRY REPORT OCTOBER 2003 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT l Scope of the document ll Geography lll Economy lV History V State Structures Vla Human Rights Issues Vlb Human Rights - Specific Groups Vlc Human Rights - Other Issues Annex A - Chronology Annex B - Political Organisations Annex C - Prominent People Annex D - References to Source Material 1. Scope of Document 1.1 This report has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The report has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The report is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the report on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. Geography 2.1 The Republic of Liberia is a coastal West African state of approximately 97,754 sq kms, bordered by Sierra Leone to the west, Republic of Guinea to the north and Côte d'Ivoire to the east. -

Threat to The

The JudicDecember 2018 ar Vol. 1. Issue: 4 y OVIA R ILDING, MON ILDING, U B E STIC U OF J OF E MPL E T THREAT TO THE SEPARATION Justice Ministry says Critical reforms are needed to promote speedy trial he Justice Ministry has justice system is critical to the OF POWERS expressed the need for promotion of access to justice for reforms in Liberia’s the ordinary Liberian people. criminal justice system Cllr. Dean said the Justice Ministry Call for Judicial oversight Tand amendment to some Liberian is currently in the process of laws to reflect current day realities. reviewing critical areas of the Justice Minister Cllr. Frank Criminal Procedure Law and body at Legislature threatens Musa Dean, Jr. suggested that in other laws they think are vital to addition to providing training enhancing access to justice and separation of powers doctrine for prosecutors and judges, rule of law. transformation in the criminal Responding to he Supreme Court of Liberia constitution of Liberia. SEE PAGE 2 says it has heard of a call or The Chief Justice’s statements were proposal for the creation contained in the 12-page speech of what is to be called a delivered during the opening of the T‘judicial oversight committee’ within October 2018 Term of the Supreme the National Legislature. Court in Monrovia on October 8, Liberia’s Chief Justice, His Honor 2018. Francis S. Korkpor, Sr. says what Also speaking on the matter, Liberia’s surprises him most about the proposal Attorney General agreed with the is the fact that the call is being made by Supreme Court, that the call for setting an unlikely source. -

The Liberian Crisis: Lessons for Intra-State Conflict Management and Prevention in Africa

The Liberian Crisis: Lessons for Intra-State Conflict Management and Prevention in Africa The Liberian Crisis: Lessons for Intra-State Conflict Management and Prevention in Africa Mike Oquaye Working Paper No. 19 June 2001 Institute for Conflict Analysis and Resolution George Mason University Aboutthe Author Professor Aaron Michael (Mike) Oquaye had a distinguished legal career before entering academe. Having been awarded a B.A. (Hons) in Political Science from the University ofGhanain 1967,hewenton tostudy law at theUniversity ofLondon, gaining bothan Honours Ll.B. anda B.L. there, before becoming a barrister at Lincolns Inn and practicing in both the HighCourt in England and later theSuperior courts of Ghana. In 1984 he began teaching in the department of Political Science at his old University ofGhana at Legon andeight years later was awarded his doctoral degree from thatuniversity, following this withpostdoctoral study at the School of Oriental andAfrican Studies of the University of London. Since that timehe has been a leading figure in thedevelopment of political studies in Ghana,helping to develop newcurricula and postgraduate work in that field. Until recendy, MikeOquayes ownworkhasfocused on the politics of hisowncountryand ofAfrica, and heiswell known asan expert on the establishment and consequences of military rule, as well as the links be tween military rule, local (district) level politics, andvarious forms ofdevel opment. He has written extensively on these subjects and his articles have appeared inAfrica Affairs, Human -

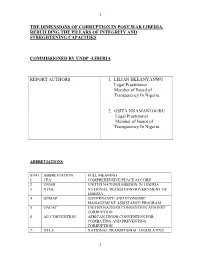

The Dimensions of Corruption in Post War Liberia, Rebuilding the Pillars of Integrity and Streghtening Capacities

1 THE DIMENSIONS OF CORRUPTION IN POST WAR LIBERIA, REBUILDING THE PILLARS OF INTEGRITY AND STREGHTENING CAPACITIES. COMMISSIONED BY UNDP -LIBERIA REPORT AUTHORS 1. LILIAN EKEANYANWU Legal Practitioner Member of Board of Transparency In Nigeria. 2. OSITA NNAMANI OGBU Legal Practitioner Member of Board of Transparency In Nigeria. ABBREVIATIONS S\NO ABBREVIATION FULL MEANING 1 CPA COMPREHENSIVE PEACE ACCORD 2. UNMIL UNITED NATIONS MISSION IN LIBERIA 3. NTGL NATIONAL TRANSITION GOVERNMENT OF LIBERIA 4. GEMAP GOVERNANCE AND ECONOMIC MANAGEMENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAM 5 UNCAC UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION 6 AU CONVENTION AFRICAN UNION CONVENTION FOR COMBATING AND PREVENTING CORRUPTION 7. NTLA NATIONAL TRANSITIONAL LEGISLATIVE 1 2 ASSEMBLY. 8. CSA CIVIL SERVICE AGENCY 9. CMC CONTRACT AND MONOPOLIES COMMISSION 10. GRC GOVERNANCE REFORM COMMISSION 11. GOPAC GLOBAL PARLIAMENTARIANS AGAINST CORRUPTION 12. APNAC AFRICAN PARLIAMENTARIANS AGAINST CORRUPTION 13. APRM AFRICAN PEER REVIEW MECHANISM 14. NEC NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION 15 AU AFRICAN UNION 16 ECOWAS ECONOMIC COMMUNITY OF WEST AFRICAN STATES TABLE OF CONTENTS S\NO CONTENT PAGE 1. PART A EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 I. Terms of Reference for the assessment 5 II. Methodology 5 III. Key Findings 6 IV. Recommendations 6 2. BACKGROUND 8 [THE CONCEPT OF PILLARS OF INTEGRITY] 3. PART B LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAME WORK ON 10 THE PILLARS OF INTEGRITY IN LIBERIA I. The Executive\Political Will-[Institutions of 10 Political and Administrative Accountability] II. The Legislature 13 III. The Judiciary 13 IV. Anti-Corruption Agency 15 V. The Media 15 VI. Civil Society 16 VII. The Civil Service Agency 16 4. THE MISSSING COMPONENTS 16 2 3 I. -

Post-Emancipation Barbadian Emigrants in Pursuit Of

“MORE AUSPICIOUS SHORES”: POST-EMANCIPATION BARBADIAN EMIGRANTS IN PURSUIT OF FREEDOM, CITIZENSHIP, AND NATIONHOOD IN LIBERIA, 1834 – 1912 By Caree A. Banton Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY August, 2013 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Richard Blackett Professor Jane Landers Professor Moses Ochonu Professor Jemima Pierre To all those who labored for my learning, especially my parents. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to more people than there is space available for adequate acknowledgement. I would like to thank Vanderbilt University, the Albert Gordon Foundation, the Rotary International, and the Andrew Mellon Foundation for all of their support that facilitated the research and work necessary to complete this project. My appreciation also goes to my supervisor, Professor Richard Blackett for the time he spent in directing, guiding, reading, editing my work. At times, it tested his patience, sanity, and will to live. But he persevered. I thank him for his words of caution, advice and for being a role model through his research and scholarship. His generosity and kind spirit has not only shaped my academic pursuits but also my life outside the walls of the academy. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to the members of my dissertation committee: Jane Landers, Moses Ochonu, and Jemima Pierre. They have provided advice and support above and beyond what was required of them. I am truly grateful not only for all their services rendered but also the kind words and warm smiles with which they have always greeted me. -

United Nations Nations Unies MISSION in LIBERIA MISSION AU LIBERIA

United Nations Nations Unies MISSION IN LIBERIA MISSION AU LIBERIA Report on the Human Rights Situation in Liberia May – October 2007 Human Rights and Protection Section UNMIL Report on the Human Rights Situation in Liberia May – October 2007 1 Table of Contents Page Executive summary ………………………………………………………. 4 Methodology ……………………………………………………………….4 Mandate of the Human Rights and Protection Section …………………5 Significant political, social and security developments …………………5 Human Rights Monitoring ………………………………………………..6 Children’s Rights ………………………………………………………….6 Right to education ………………………………………………….6 Violence against children ………………………………………….. 7 Human Rights and orphanages ……………………………………. 8 Law Enforcement …………………………………………………………9 Improper use of restraints and alleged ill-treatment ………………..9 Extortion by LNP officials ………………………………………… 9 Mob justice …………………………………………………………10 The Judiciary ……………………………………………………………...10 Slow progress in hearing of cases in courts ……………………….. 10 Lack of resources and insufficient skills among jurors …………….11 Corrupt practices by court officials and interference in the operation of the justice system ………………………………12 Justices of the Peace practising without licences ………………….. 13 Abuse of authority ………………………………………………….13 Misapplication of the law ………………………………………….. 14 Human Rights in Prisons and Places of Detention ……………………...15 Poor conditions of detention and lack of facilities ………………… 15 Poor management of facilities …………………………………….. 16 Unauthorised detention facilities ………………………………….. 16 Rent seeking practices -

Implementation of Abuja II Accord and Post-Conflict Security in Liberia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2007-06 Implementation of Abuja II accord and post-conflict security in Liberia Ikomi, Emmanuel Oritsejolomi Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3440 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS IMPLEMENTATION OF ABUJA II ACCORD AND POST- CONFLICT SECURITY IN LIBERIA by Emmanuel Oritsejolomi Ikomi June 2007 Thesis Advisor: Letitia Lawson Second Reader: Karen Guttieri Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2007 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Implementation of Abuja II Accord and Post- 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Conflict Security in Liberia 6. AUTHOR Emmanuel Oritsejolomi Ikomi 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8.