Increasing Confidence in the Liberian Judiciary: a Shift in the Dispensation of Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Commentary on the Meaning

A COMMENTARY ON THE MEANING OF THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA David C. Williams Jallah A. Barbu April 1, 2009 DEDICATION For the People of Liberia TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION PART I: THE TRIPARTITE SYSTEM OF GOVERNMENT CHAPTER ONE: THE GENERAL NATURE OF THE SEPARATION OF POWERS SUBPART I(A): THE JUDICIAL BRANCH CHAPTER TWO: THE JUDICIAL POWER OF THE JUDICIAL BRANCH CH. TWO(a): The POWER TO DECIDE CASES CH. TWO(b): THE POWER TO ENFORCE JUDICIAL MANDATES Ch. Two(b)(1): Presidential Immunity from Court Process Ch. Two(b)(2): The Exclusive Power of the Executive to Enforce the Law Ch. Two(b)(3): The Differences Between the Two Rationales for the Court’s Inability to Order the President to Enforce Its Mandates CH. TWO(c): THE EXCLUSION OF OTHER BRANCHES FROM JUDICIAL FUNCTIONS Ch. Two(c)(1): The Exclusion of the Other Branches from Deciding Cases Ch. Two(c)(1)(i): The Exclusion of the Legislature from Deciding Cases Ch. Two(c)(1)(ii): The Exclusion of the Executive from Deciding Cases Ch. Two(c)(1)(iii): The Limited Power of Executive Agencies to Decide Cases Ch. Two(c)(2): Prohibition on Attempts by the Other Branches to Interfere with the Supreme Court CH. TWO(d): THE POWER TO INTERPRET STATUTES Ch. Two(d)(1): The Power to Determine the Intent of the Legislature But Not to Legislate Ch. Two(d)(2): Prohibition on Interpreting Statutes According to the Court’s Own Policy Views i Ch. Two(d)(3): The Importance of the Words of the Statute in Determining Legislative Intent Ch. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

UN FOCUS June - August 2011

Vol. 7, No. 04 UN FOCUS June - August 2011 Liberia Goes to the Polls Women Demand More Participation Code of Conduct to Reduce Political Wrangling Message from the Special Representative of the Secretary-General s Liberia stands ready the future direction of the country; to go back to the polls and it is heartening to note that 49% to elect its second post- of all registered voters are women, conflict democratic gov- showing great interest from Liberian ernment, the country women to make their voices heard. Awill hopefully once again proudly The 2011 national elections are declare that democracy, and peace, wholly run by Liberians, unlike in are here to stay. 2005. The United Nations has been A national referendum was suc- engaged with the NEC, but only to cessfully held on 23 August, dem- help coordinate international assist- onstrating the National Elections ance, fill logistic gaps, and to ensure Commission’s increasing capabil- dialogue between the NEC and po- ity to conduct a national event of litical parties to foment agreement grand magnitude, but also that the on the process. Liberian people respect the demo- Elections are always a challenging cratic process. Referendum Day was exercise in any country, but by up- peaceful, and although not all politi- holding the nation’s interest above cal parties were in agreement with personal ambitions and adhering to the holding of the referendum, the the rule of law, political parties and people expressed their will through candidates play a major part in en- the vote, or even through the deci- suring a peaceful process. -

Threat to The

The JudicDecember 2018 ar Vol. 1. Issue: 4 y OVIA R ILDING, MON ILDING, U B E STIC U OF J OF E MPL E T THREAT TO THE SEPARATION Justice Ministry says Critical reforms are needed to promote speedy trial he Justice Ministry has justice system is critical to the OF POWERS expressed the need for promotion of access to justice for reforms in Liberia’s the ordinary Liberian people. criminal justice system Cllr. Dean said the Justice Ministry Call for Judicial oversight Tand amendment to some Liberian is currently in the process of laws to reflect current day realities. reviewing critical areas of the Justice Minister Cllr. Frank Criminal Procedure Law and body at Legislature threatens Musa Dean, Jr. suggested that in other laws they think are vital to addition to providing training enhancing access to justice and separation of powers doctrine for prosecutors and judges, rule of law. transformation in the criminal Responding to he Supreme Court of Liberia constitution of Liberia. SEE PAGE 2 says it has heard of a call or The Chief Justice’s statements were proposal for the creation contained in the 12-page speech of what is to be called a delivered during the opening of the T‘judicial oversight committee’ within October 2018 Term of the Supreme the National Legislature. Court in Monrovia on October 8, Liberia’s Chief Justice, His Honor 2018. Francis S. Korkpor, Sr. says what Also speaking on the matter, Liberia’s surprises him most about the proposal Attorney General agreed with the is the fact that the call is being made by Supreme Court, that the call for setting an unlikely source. -

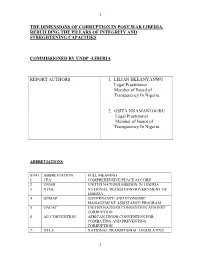

The Dimensions of Corruption in Post War Liberia, Rebuilding the Pillars of Integrity and Streghtening Capacities

1 THE DIMENSIONS OF CORRUPTION IN POST WAR LIBERIA, REBUILDING THE PILLARS OF INTEGRITY AND STREGHTENING CAPACITIES. COMMISSIONED BY UNDP -LIBERIA REPORT AUTHORS 1. LILIAN EKEANYANWU Legal Practitioner Member of Board of Transparency In Nigeria. 2. OSITA NNAMANI OGBU Legal Practitioner Member of Board of Transparency In Nigeria. ABBREVIATIONS S\NO ABBREVIATION FULL MEANING 1 CPA COMPREHENSIVE PEACE ACCORD 2. UNMIL UNITED NATIONS MISSION IN LIBERIA 3. NTGL NATIONAL TRANSITION GOVERNMENT OF LIBERIA 4. GEMAP GOVERNANCE AND ECONOMIC MANAGEMENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAM 5 UNCAC UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION AGAINST CORRUPTION 6 AU CONVENTION AFRICAN UNION CONVENTION FOR COMBATING AND PREVENTING CORRUPTION 7. NTLA NATIONAL TRANSITIONAL LEGISLATIVE 1 2 ASSEMBLY. 8. CSA CIVIL SERVICE AGENCY 9. CMC CONTRACT AND MONOPOLIES COMMISSION 10. GRC GOVERNANCE REFORM COMMISSION 11. GOPAC GLOBAL PARLIAMENTARIANS AGAINST CORRUPTION 12. APNAC AFRICAN PARLIAMENTARIANS AGAINST CORRUPTION 13. APRM AFRICAN PEER REVIEW MECHANISM 14. NEC NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION 15 AU AFRICAN UNION 16 ECOWAS ECONOMIC COMMUNITY OF WEST AFRICAN STATES TABLE OF CONTENTS S\NO CONTENT PAGE 1. PART A EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 I. Terms of Reference for the assessment 5 II. Methodology 5 III. Key Findings 6 IV. Recommendations 6 2. BACKGROUND 8 [THE CONCEPT OF PILLARS OF INTEGRITY] 3. PART B LEGAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAME WORK ON 10 THE PILLARS OF INTEGRITY IN LIBERIA I. The Executive\Political Will-[Institutions of 10 Political and Administrative Accountability] II. The Legislature 13 III. The Judiciary 13 IV. Anti-Corruption Agency 15 V. The Media 15 VI. Civil Society 16 VII. The Civil Service Agency 16 4. THE MISSSING COMPONENTS 16 2 3 I. -

Post-Emancipation Barbadian Emigrants in Pursuit Of

“MORE AUSPICIOUS SHORES”: POST-EMANCIPATION BARBADIAN EMIGRANTS IN PURSUIT OF FREEDOM, CITIZENSHIP, AND NATIONHOOD IN LIBERIA, 1834 – 1912 By Caree A. Banton Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY August, 2013 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Richard Blackett Professor Jane Landers Professor Moses Ochonu Professor Jemima Pierre To all those who labored for my learning, especially my parents. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to more people than there is space available for adequate acknowledgement. I would like to thank Vanderbilt University, the Albert Gordon Foundation, the Rotary International, and the Andrew Mellon Foundation for all of their support that facilitated the research and work necessary to complete this project. My appreciation also goes to my supervisor, Professor Richard Blackett for the time he spent in directing, guiding, reading, editing my work. At times, it tested his patience, sanity, and will to live. But he persevered. I thank him for his words of caution, advice and for being a role model through his research and scholarship. His generosity and kind spirit has not only shaped my academic pursuits but also my life outside the walls of the academy. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to the members of my dissertation committee: Jane Landers, Moses Ochonu, and Jemima Pierre. They have provided advice and support above and beyond what was required of them. I am truly grateful not only for all their services rendered but also the kind words and warm smiles with which they have always greeted me. -

United Nations Nations Unies MISSION in LIBERIA MISSION AU LIBERIA

United Nations Nations Unies MISSION IN LIBERIA MISSION AU LIBERIA Report on the Human Rights Situation in Liberia May – October 2007 Human Rights and Protection Section UNMIL Report on the Human Rights Situation in Liberia May – October 2007 1 Table of Contents Page Executive summary ………………………………………………………. 4 Methodology ……………………………………………………………….4 Mandate of the Human Rights and Protection Section …………………5 Significant political, social and security developments …………………5 Human Rights Monitoring ………………………………………………..6 Children’s Rights ………………………………………………………….6 Right to education ………………………………………………….6 Violence against children ………………………………………….. 7 Human Rights and orphanages ……………………………………. 8 Law Enforcement …………………………………………………………9 Improper use of restraints and alleged ill-treatment ………………..9 Extortion by LNP officials ………………………………………… 9 Mob justice …………………………………………………………10 The Judiciary ……………………………………………………………...10 Slow progress in hearing of cases in courts ……………………….. 10 Lack of resources and insufficient skills among jurors …………….11 Corrupt practices by court officials and interference in the operation of the justice system ………………………………12 Justices of the Peace practising without licences ………………….. 13 Abuse of authority ………………………………………………….13 Misapplication of the law ………………………………………….. 14 Human Rights in Prisons and Places of Detention ……………………...15 Poor conditions of detention and lack of facilities ………………… 15 Poor management of facilities …………………………………….. 16 Unauthorised detention facilities ………………………………….. 16 Rent seeking practices -

Human Rights Report Bi-Monthly Report

FOUNDATION FOR HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENSE INTERNATIONAL (FOHRD) Human Rights Report Bi-Monthly Report Published June 1, 2021 FOHRD’s Department of Complaints and Investigations 1 | P a g e Table of Content TABLE PAGE Cover 1 Content 2 Introduction 3 A Message from the Executive Director 4 Executive Summary and Highlights 5 Freedom of Expression 6 Allegation of Corruption 7 - 8 Pre-Trial Detention & Denial of Fair Trial 9 - 10 Inadequate Health Services Delivery 11 Violence and Excessive Use of Force 12 Prison Monitoring 13 Recommendations 14 2 | P a g e INTRODUCTION International standard demands protection for the rights of every member of the human family, and that those in position of power take every appropriate step to protect the most vulnerable, including children and the elderly. The dispensation of justice must be done on the basis of fairness, and those accused of wrongdoings must be tried in a court of competent jurisdiction; this is the principle of good moral ethics that will advance the cause of humanity and make the world a better place. The Foundation for Human Rights Defense International (FOHRD) takes its ethical and moral responsibility to speak against the ills of society seriously and prides itself in performing said responsibility with the utmost professionalism and objectivity. The field agents who contributed to this report are dedicated patriots, who care deeply about the future of human rights and democracy in Liberia, a cause to which the Foundation for Human Rights Defense International is fully committed. This fourteen (14)-page report represents the findings of FOHRD’s Department of Complaints and Investigations (DCI) over the last two months. -

Constitution Review Committee (Crc)

The Constitution Review Committee considers communication an essential tool for the implementation of its mandate. This tool consists of person to person communication, interactive meetings, radio talk shows, media engagement and many more. The Committee began weekly radio programs with the nation’s broadcaster, ELBC and LWDR on a daily basis. The CRC has also engaged communities, churches, mosque, intellectual centers and hospitals to explain the constitution review process to the people. As you go through this file, you will encounter the people and what their concerns are. CONSTITUTION REVIEW COMMITTEE (CRC) INTERACTIVE LIVE RADIO TALK SHOWS UNEDITED VERSIONS The below matrix represents callers’ views and names on the Talk Show: “THE CONSTITUTION AND YOU” held twice a week every Wednesdays from 10:45---11:45 am and Thursday from 8:15---9:15pmon a state run radio station ELBC. This report focuses the concerns and questions of callers only. YEAR MONTH WEEK NAME LOCATION QUESTIONS/CONCERNS DATE DAY GUEST/S 2013 July Augustin Gardnerville Why did the House of Representative declare Mary Broh & 17th Wed Cllr. Scott & Rev. Dr. e Grace Kpaan non-governmental materials? Ndaborlor Brown Charles Congo Town Why is the Vice President in the Executive but heading the Goffah Community Senate despite the separation of power? Sam Harbel- How do citizens remove the president whenever he /she is not Freeman Firestone serving them well? Same J. Pipeline Road Teaching the constitution in schools will help make people to be Baysah law abiding. Education Ministry should work with the CRC to teach the Constitution in all schools. -

Supreme Court Acknowledges Challenging Time As Justice Ja'neh

The JudicJanuary - March 2019 ar Vol. 1. Issue: 5 y Supreme Court Acknowledges Challenging Time as Justice Ja’neh Faces Impeachment he Supreme Court of Liberia has Chief Justice Francis S. Korkpor, Sr.’s statement about the Court, is unprecedented in the history of our country.” acknowledged that it is experiencing what it challenges the high court of Liberia is going through was “To the best of my recollection,” Chief Justice Korkpor calls “a challenging time.” in clear reference to the impeachment proceeding against noted, “no impeachment proceeding in our nation has In the address delivered at the opening of the the most senior associate justice on the Korkpor Bench. March 2019 Term of the Supreme Court, the According to the Chief Justice, “the impeachment trial Chief Justice of Liberia said “it is no secret that this court going on at the Liberian Senate involving Mr. Justice Tis going through a challenging time.” Kabineh M. Ja’neh, a member of this SEE PAGE 2 Training critical for functional Judiciary …Justice Minister asserts prosecutors. Responding to the address of Chief Justice Francis S. Korkpor, Sr. at the opening of the March 2019 Term of he Minister of Justice/Attorney General of the Supreme Court on Monday, March 11, 2019, Cllr. the Republic of Liberia says the Ministry Dean agreed that the proceeding against Justice Kabineh welcomes the training of judicial officials, Ja’neh was unprecedented, adding that these are indeed especially magistrates at the James A. A. challenging times for the Judiciary. Pierre Judicial Institute at the Temple of He however expressed confidence that with divine Justice in Montserrado County. -

Plaintiffs Motion to Proceed Anonymously and Declarations

Case 2:18-cv-00569-PBT Document 15-1 Filed 04/09/18 Page 1 of 12 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT IN THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA JANE W, in her individual capacity, and in her capacity as the personal representative of the estates of her relatives, James W, Julie W and Jen W, JOHN X, in his individual capacity, and in his capacity as the personal representative of the estates of his relatives, Jane X, Julie X, James X and Case No. 2:18-CV-00569-PBT Joseph X, JOHN Y, in his individual capacity, and JOHN Z, in his individual capacity, Plaintiffs, v. MOSES W. THOMAS, Defendant. MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTION OF PLAINTIFFS JANE W, JOHN X, JOHN Y, AND JOHN Z FOR LEAVE TO PROCEED ANONYMOUSLY I. INTRODUCTION Plaintiffs Jane W, John X, John Y, and John Z (“Plaintiffs”) submit this Memorandum of Law in Support of Their Motion for Leave to File Anonymously. Plaintiffs—all Liberian citizens living in Liberia—filed a Complaint on February 12, 2018, alleging that Defendant Moses Thomas (“Thomas”) is responsible for extrajudicial killing, torture, war crimes, crimes against humanity and other serious human rights abuses committed against them and their families during the First Liberian Civil War (the “Civil War”). Thomas, a commander in the Liberian armed forces during the Civil War, directed and participated in a 106961300v.1 Case 2:18-cv-00569-PBT Document 15-1 Filed 04/09/18 Page 2 of 12 hellish massacre of 600 Liberian civilians confined within the sanctuary of the St. -

Republic of Liberia Executive Mansion Monrovia, Liberia

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA EXECUTIVE MANSION MONROVIA, LIBERIA Office of the Press Secretary to the President Cell: 0886-580034/0777580034 Email: [email protected] [email protected] President Sirleaf Announces Death of Former Chief Justice Johnnie Lewis; Expresses Condolence to the Official and Biological Families, Friends and the National Bar Association (MONROVIA, LIBERIA – Thursday, January 22, 2015) President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf has expressed heartfelt condolences to the official family – the Honorable Supreme Court of Liberia - and the Liberian National Bar Association; as well as the biological family and friends of His Honor Johnnie N. Lewis, former Chief Justice of the Honorable Supreme Court of Liberia. The late Chief Justice Lewis died Wednesday evening, January 21, in Monrovia en route to the John F. Kennedy Medical Center. He was 69 years old. According to an Executive Mansion release made the assertion when she officially announced the death of the former Chief Justice in a brief statement to the nation on Thursday, January 22, 2015. “The Government of Liberia notes with profound regrets the passing of former Chief Justice of the Republic of Liberia, His Honor Johnnie N. Lewis, a long tenured public servant in this country and in the international community,” she said. The Liberian leader indicated that the late Counselor served his country and the international community with extraordinary talent, intellect, knowledge and brilliance, and urged all to grant him the respect that he duly deserves. Cllr. Lewis (69) was appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Liberia in 2006 until his early retirement became effective on September 10, 2012.