How Nordic Are the Old Nordic Laws?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

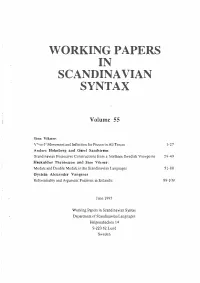

Working Papers in Scandina Vian Syntax

WORKING PAPERS IN SCANDINA VIAN SYNTAX Volume 55 Sten Vikner: V0-to-l0 Mavement and Inflection for Person in AllTenses 1-27 Anders Holmberg and Gorel Sandstrom: Scandinavian Possessive Construerions from a Northem Swedish Viewpoint 29-49 Hoskuldur Thrainsson and Sten Vikner: Modals and Double Modals in the Scandinavian Languages 51-88 Øystein Alexander Vangsnes Referentiality and Argument Positions in leelandie 89-109 June 1995 Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax Department of Scandinavian Languages Helgonabacken 14 S-223 62 Lund Sweden V0-TO-JO MOVEMENT AND INFLECTION FOR PERSON IN ALL TENSES Sten Vilener Institut furLinguistik/Germanistik, Universitat Stuttgart, Postfach 10 60 37, D-70049 Stuttgart, Germany E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACf Differentways are considered of formulating a conneelion between the strength of verbal inflectional morphology and the obligatory m ovement of the flnite verb to J• (i.e. to the lefl of a medial adverbial or of negation), and two main alternatives are anived at. One is from Rohrbacher (1994:108):V"-to-1• movement iff 151 and 2nd person are distinctively marked at least once. The other will be suggesled insection 3: v•-to-J• mavement iff all"core' tenses are inflectedfor person. It is argued that the latter approach has certain both conceptual and empirical advantages ( e.g. w hen considering the loss of v•-to-J• movement in English). CONTENTS 1. Introduction: v•-to-J• movement ...................................................................................................................................... -

Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present (Impact: Studies in Language and Society)

<DOCINFO AUTHOR ""TITLE "Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present"SUBJECT "Impact 18"KEYWORDS ""SIZE HEIGHT "220"WIDTH "150"VOFFSET "4"> Germanic Standardizations Impact: Studies in language and society impact publishes monographs, collective volumes, and text books on topics in sociolinguistics. The scope of the series is broad, with special emphasis on areas such as language planning and language policies; language conflict and language death; language standards and language change; dialectology; diglossia; discourse studies; language and social identity (gender, ethnicity, class, ideology); and history and methods of sociolinguistics. General Editor Associate Editor Annick De Houwer Elizabeth Lanza University of Antwerp University of Oslo Advisory Board Ulrich Ammon William Labov Gerhard Mercator University University of Pennsylvania Jan Blommaert Joseph Lo Bianco Ghent University The Australian National University Paul Drew Peter Nelde University of York Catholic University Brussels Anna Escobar Dennis Preston University of Illinois at Urbana Michigan State University Guus Extra Jeanine Treffers-Daller Tilburg University University of the West of England Margarita Hidalgo Vic Webb San Diego State University University of Pretoria Richard A. Hudson University College London Volume 18 Germanic Standardizations: Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert and Wim Vandenbussche Germanic Standardizations Past to Present Edited by Ana Deumert Monash University Wim Vandenbussche Vrije Universiteit Brussel/FWO-Vlaanderen John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam/Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements 8 of American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Germanic standardizations : past to present / edited by Ana Deumert, Wim Vandenbussche. -

Political Participation of National Minorities in the Danish-German Border Region

Political Participation of National Minorities in the Danish-German Border Region A series of studies on two hard-to-identify populations in a role-model-region Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) an der Fakultät Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften, Fachbereich Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Hamburg vorgelegt von Adrian Schaefer-Rolffs Hamburg, den 06.06.2016 Erstgutachter : Prof. Dr. Kai-Uwe Schnapp Zweitgutachterin : Prof. Dr. Tove Hansen Malloy Tag der Disputation : 26.09.2016 “Always the hard way. Nothing was ever handed to me. Always the hard way. You taught me truth, you gave me strength. I learned everything the hard way” (Nicholas Jett and Scott C. Vogel) Contents Contents Contents ............................................................................................. V List of tables ............................................................................................ IX List of figures .......................................................................................... XI Abbreviations ....................................................................................... XIII Acknowledgements ................................................................................ XV Part I. Introductory part ..................................... 1 1. Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 1.1. Positioning and reflexivity .................................................................... 7 1.2. Relevant literature -

Analysis of the Emerging Situation of Resistance to Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors in Pyrenophora Teres and Zymoseptoria Tritici in Europe

Universität Hohenheim Institut für Phytomedizin Fachgebiet Phytopathologie Prof. Dr. Ralf T. Vögele Analysis of the emerging situation of resistance to succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors in Pyrenophora teres and Zymoseptoria tritici in Europe Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Agrarwissenschaften vorgelegt der Fakultät Agrarwissenschaften von Dipl. Agr. Biol. Alexandra Rehfus aus Leonberg 2018 Diese Arbeit wurde unterstützt und finanziert durch die BASF SE, Unternehmensbereich Pflanzenschutz, Forschung Fungizide, Limburgerhof. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde am 15.05.2017 von der Fakultät Agrarwissenschaften der Universität Hohenheim als „Erlangung des Doktorgrades an der agrarwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Hohenheim in Stuttgart“ angenommen. Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 14.11.2017 1. Dekan: Prof. Dr. R. T. Vögele Berichterstatter, 1. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. R. T. Vögele Mitberichterstatter, 2. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. O. Spring 3. Prüfer: Prof. Dr. Dr. C. P. W. Zebitz Leiter des Kolloquiums: Prof. Dr. J. Wünsche Table of contents III Table of contents Table of contents ................................................................................................. III Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... VII Figures ................................................................................................................. IX Tables ................................................................................................................. -

THE DISCOVERY of the BALTIC the NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic C

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC THE NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD Peoples, Economies and Cultures EDITORS Barbara Crawford (St. Andrews) David Kirby (London) Jon-Vidar Sigurdsson (Oslo) Ingvild Øye (Bergen) Richard W. Unger (Vancouver) Przemyslaw Urbanczyk (Warsaw) VOLUME 15 THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075-1225) BY NILS BLOMKVIST BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Knight sitting on a horse, chess piece from mid-13th century, found in Kalmar. SHM inv. nr 1304:1838:139. Neg. nr 345:29. Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, the National Heritage Board, Stockholm. Brill Academic Publishers has done its best to establish rights to use of the materials printed herein. Should any other party feel that its rights have been infringed we would be glad to take up contact with them. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blomkvist, Nils. The discovery of the Baltic : the reception of a Catholic world-system in the European north (AD 1075-1225) / by Nils Blomkvist. p. cm. — (The northern world, ISSN 1569-1462 ; v. 15) Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 90-04-14122-7 1. Catholic Church—Baltic Sea Region—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Baltic Sea Region—Church history. I. Title. II. Series. BX1612.B34B56 2004 282’485—dc22 2004054598 ISSN 1569–1462 ISBN 90 04 14122 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

Þingvellir National Park

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1152.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Þingvellir National Park DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 7th July 2004 STATE PARTY: ICELAND CRITERIA: C (iii) (vi) CL DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Report of the 28th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (iii): The Althing and its hinterland, the Þingvellir National Park, represent, through the remains of the assembly ground, the booths for those who attended, and through landscape evidence of settlement extending back possibly to the time the assembly was established, a unique reflection of mediaeval Norse/Germanic culture and one that persisted in essence from its foundation in 980 AD until the 18th century. Criterion (vi): Pride in the strong association of the Althing to mediaeval Germanic/Norse governance, known through the 12th century Icelandic sagas, and reinforced during the fight for independence in the 19th century, have, together with the powerful natural setting of the assembly grounds, given the site iconic status as a shrine for the national. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Þingvellir (Thingvellir) is the National Park where the Althing - an open-air assembly, which represented the whole of Iceland - was established in 930 and continued to meet until 1798. Over two weeks a year, the assembly set laws - seen as a covenant between free men - and settled disputes. The Althing has deep historical and symbolic associations for the people of Iceland. Located on an active volcanic site, the property includes the Þingvellir National Park and the remains of the Althing itself: fragments of around 50 booths built of turf and stone. -

The Hostages of the Northmen: from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages

Part IV: Legal Rights It has previously been mentioned how hostages as rituals during peace processes – which in the sources may be described with an ambivalence, or ambiguity – and how people could be used as social capital in different conflicts. It is therefore important to understand how the persons who became hostages were vauled and how their new collective – the new household – responded to its new members and what was crucial for his or her status and participation in the new setting. All this may be related to the legal rights and special privileges, such as the right to wear coat of arms, weapons, or other status symbols. Personal rights could be regu- lated by agreements: oral, written, or even implied. Rights could also be related to the nature of the agreement itself, what kind of peace process the hostage occurred in and the type of hostage. But being a hostage also meant that a person was subjected to restric- tions on freedom and mobility. What did such situations meant for the hostage-taking party? What were their privileges and obli- gations? To answer these questions, a point of departure will be Kosto’s definition of hostages in continental and Mediterranean cultures around during the period 400–1400, when hostages were a form of security for the behaviour of other people. Hostages and law The hostage had its special role in legal contexts that could be related to the discussion in the introduction of the relationship between religion and law. The views on this subject are divided How to cite this book chapter: Olsson, S. -

Homicides in Norway

Homicides in Norway: Exploring the Characteristics and Decline Between 1991 and 2015 Malin Sæth Hanset Spring 2019 Master’s thesis in Criminology Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law Faculty of Law University of Oslo Homicides in Norway: Exploring the Characteristics and Decline between 1991 and 2015 II Copyright Malin Sæth Hanset 2019 Homicides in Norway: Exploring the Characteristics and Decline between 1991 and 2015 Malin Sæth Hanset http://www.duo.uio.no Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo III Summary Title: Homicides in Norway: Exploring the Characteristics and Decline Between 1991 and 2015 Author: Malin Sæth Hanset Supervisor: Nina Jon Department of Criminology and Sociology of Law Faculty of Law University of Oslo Spring 2019 This thesis considers homicides in Norway between 1991 and 2015 and the decline that can be seen in this period. What it seeks to do is to look into what characterise homicides in this period, in which type of homicide can the decline be seen, has every type of homicide seen a decrease and lastly, has specific types of homicides disappeared or experienced a more dramatic decrease. This was done by looking at the Homicide Overview from the National Criminal Investigation Service Norway and by a content analysis of 82 judicial verdicts. It is quantitative content analysis as it counts variables, but it is mostly a qualitative analysis as it seeks to give a deeper understanding of the homicides. The homicides were divided into four categories; intimate partner homicides; homicides between friends, acquaintances and colleagues; familial homicides; and homicides between other relations (strangers, the perpetrators/victim used a service that the victim/perpetrator provided, and unspecified relations). -

The De-Germanicising of English(1)

THE DE-GERMANICISING OF ENGLISH(1) Paul Edmund DAVENPORT English is not an isolated tongue but a member of the Germanic languages, which are in turn members of the Indo-Europan language family. In this case, in saying that certain languages are 'members' of a language 'family', we mean that the said languages have a common origin. The so-called Germanic languages of today (principally English, Dutch, German, and the Scandinavian languages(5) have a common origin in an ancient, unrecorded language usually called Proto- Germanic. This Proto-Germanic, like Latin, Greek, Sanskrit, and the ancient Celtic and Slavonic languages, evolved from a still more ancient language usually referred to as the Proto-Indo-European parent language. The common application in historical linguistics of such anthropological terms of kinship as 'parent' and 'family', as I have just used them, and 'ancestor', 'descendant' , 'sister' (as in 'English and German are sister languages') is quite relevant to the present discussion. Human offspring normally reproduce and thus continue some of the physical features and personality traits of their parents; at the same time an otherwise unique personality develops in each specimen, prompted by inherent tendencies and reactions to environmental influences. In language, of course, quite unlike the animal kingdom, the chain of connection between 'parent' and 'child' is one that evolves slowly and is broken only gradually. Still, when we look at Old English and modern English, or Latin and French, or Sanskrit and Hindi, it is easy to discern a convenient parallelism with the situation of human kinship in the phenomena of historically verifiable lineal connection, the continua- tion of certain characteristics (such as lexical items and various grammatical feat- ures), the development of apparently inherent tendencies (certain types of phono- logical and grammatical change), and environmental influences (the influence of Norse in the reduction of Old English inflections or the influence of French on the Middle English vocabulary, for example). -

Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege's 1993 Translation Of

Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege’s 1993 Translation of Rasmus Rask’s Prize Essay of 1818 Frans Gregersen To cite this version: Frans Gregersen. Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege’s 1993 Translation of Rasmus Rask’s Prize Essay of 1818. 2013. hprints-00786171 HAL Id: hprints-00786171 https://hal-hprints.archives-ouvertes.fr/hprints-00786171 Preprint submitted on 7 Feb 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Introduction to the New Edition of Niels Ege’s 1993 Translation of Rasmus Rask’s Prize Essay of 1818* 1. Introduction This edition constitutes a photographic reprint of the English edition of Rasmus Rask‘s prize essay of 1818 which appeared as volume XXVI in the Travaux du Cercle Linguistique de Copenhague in 1993. The only difference, besides the new front matter, is the present introduction, which serves to introduce the author Rasmus Rask, the man and his career, and to contextualize his famous work. It also serves to introduce the translation and the translator, Niels Ege (1927–2003). The prize essay was published in Danish in 1818. In contrast to other works by Rask, notably his introduction to the study of Icelandic (on which, see further below), it was never reissued until Louis Hjelmslev (1899–1965) published a corrected version in Danish as part of his edition of Rask‘s selected works (Rask 1932). -

Magnus Barefoot from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Magnus Barefoot From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the second Norwegian king named Magnus Olafsson. For the earlier Norwegian king, see Magnus the Good. Magnus Barefoot Drawing of a coin from the reign of Magnus Barefoot (with confused legend)[1] King of Norway Reign September 1093 – 24 August 1103 Predecessor Olaf III Successor Sigurd I, Eystein I and Olaf Magnusson Co-ruler Haakon Magnusson (until 1095) King of Dublin Reign 1102–1103 Predecessor Domnall Gerrlámhach Successor Domnall Gerrlámhach Born 1073 Norway Died 24 August 1103 (aged 29–30) near River Quoile, Downpatrick Ulster, Ireland Burial near St. Patrick's Church, Downpatrick, Ulster, Ireland Consort Margaret of Sweden Eystein I of Norway Issue Sigurd I of Norway Olaf Magnusson of Norway Ragnild Magnusdotter Tora Magnusdatter Harald IV Gille (claimed) Sigurd Slembe (claimed) Magnus Raude (claimed) Full name Magnús Óláfsson House Hardrada Father Olaf III of Norway Mother Tora?; disputed (see below) Religion Roman Catholicism Magnus Olafsson (Old Norse: Magnús Óláfsson, Norwegian: Magnus Olavsson; 1073 – 24 August 1103), better known as Magnus Barefoot (Old Norse: Magnús berfœttr, Norwegian: Magnus Berrføtt),[2] was King of Norway (as Magnus III) from 1093 until his death in 1103. His reign was marked by aggressive military campaigns and conquest, particularly in the Norse-dominated parts of the British Isles, where he extended his rule to the Kingdom of the Isles and Dublin. His daughter, Ragnhild, was born in 1090. As the only son of King Olaf Kyrre, Magnus was proclaimed king in southeastern Norway shortly after his father's death in 1093. In the north, his claim was contested by his cousin, Haakon Magnusson (son of King Magnus Haraldsson), and the two co-ruled uneasily until Haakon's death in 1095. -

New Datings of Three Courtyard Sites in Rogaland

Frode Iversen 26 Emerging Kingship in the 8th Century? New Datings of three Courtyard Sites in Rogaland The Norwegian ‘courtyard sites’ have variously been interpreted as special cultic, juridical, or military assembly sites, which served at more than the purely local level. Previously, on the basis of studies of artefacts and finds of pottery from these structures, the principal period of use of the courtyard sites in Rogaland has been dated to the early and late Roman Iron Age (AD 1–400) and the Migration Period (AD 400–550) through c. AD 600. To test the validity of this date range, the Avaldsnes Royal Manor Project has commissioned thirty new radiocarbon datings of material from three courtyard sites in Rogaland that Jan Petersen had excavated in 1938–50. These are Øygarden, Leksaren, and Klauhaugane; the latter is one of the largest courtyard sites in Norway. Øygarden has not previously been radiocarbon dated. For Klauhaugene, only a few radiocarbon dates had been obtained prior to this study. Leksaren was radiocarbon dated in the 1990s, with the results rather surprisingly indicating that its use continued into the 7th century. The present study demonstrates that the three investigated sites were in use during the Merovingian Period (AD 550–800) – a finding that both confirms and develops previous chronological frameworks. The courtyard sites in Rogaland fell out of use earlier than in other areas along the western coast of Norway. It is therefore suggested that their abandonment was connected to the emergence in the 8th century of royal power accompanied by greater control over jurisdiction – a royal power that subsequently expanded within the coastal zone.