Games Writing, Hardware Hacking, and the Will to Mod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Canon Cat After of Release Before Macintosh

LORI EMERSON & FINN BRUNTON THE CANON CAT PROCESSING ADVANCED WORK In the fall of 2014, Finn Brunton, an assistant professor at NYU, contacted Lori Emerson, Director of the Media Archaeology Lab (MAL) at the University of Colorado, Boulder, about a rare fi nd he came across on ebay: a Canon Cat, which billed itself in 1986 as an “advanced work processor.” The MAL wasn’t immediately able to purchase the machine; however, Brunton purchased the Canon Cat with the agreement that he’d experiment with the Canon Cat for six months or so, sell it to the MAL, and then he and Emerson would co-write a piece – now, this piece – on the obscure machine from an ever-more distant past. Here, we hope to give you a glimpse into what computing could have been and still could be. 353 [SHIFT]+[DOCUMENT] [SHIFT]+[DOCUMENT] Who will the user be? The shape that early personal Jef Raskin began to work on designing the Canon Cat after computing takes rests in part on this question, with he left Apple in 1982, two years before release of Macintosh. its implicit temporal paradox. The scenario, or persona, The Cat was then introduced to the public by Canon in 1987 or model, or instance of the user threads through the for $1495 – roughly $3100 in 2015. Although the Cat was production of the machine, from input devices and discontinued after only six months, around 20,000 units performance criteria to software, industrial design, and were sold during this time. The Canon Cat fascinates me marketing. -

Retrocomputing As Preservation and Remix

Retrocomputing as Preservation and Remix Yuri Takhteyev Quinn DuPont University of Toronto University of Toronto [email protected] [email protected] Abstract This paper looks at the world of retrocomputing, a constellation of largely non-professional practices involving old computing technology. Retrocomputing includes many activities that can be seen as constituting “preservation.” At the same time, it is often transformative, producing assemblages that “remix” fragments from the past with newer elements or joining together historic components that were never combined before. While such “remix” may seem to undermine preservation, it allows for fragments of computing history to be reintegrated into a living, ongoing practice, contributing to preservation in a broader sense. The seemingly unorganized nature of retrocomputing assemblages also provides space for alternative “situated knowledges” and histories of computing, which can sometimes be quite sophisticated. Recognizing such alternative epistemologies paves the way for alternative approaches to preservation. Keywords: retrocomputing, software preservation, remix Recovering #popsource In late March of 2012 Jordan Mechner received a shipment from his father, a box full of old floppies. Among them was a 3.5 inch disk labelled: “Prince of Persia / Source Code (Apple) / ©1989 Jordan Mechner (Original).” Mechner’s announcement of this find on his blog the next day took the world of nerds by storm.1 Prince of Persia, a game that Mechner single-handedly developed in the late 1980s, revolutionized computer games when it came out due to its surprisingly realistic representation of human movement. After being ported to DOS and Apple’s Mac OS in the early 1990s the game sold 2 million copies (Pham, 2001). -

Do-It-Yourself Devices: Personal Fabrication of Custom Electronic Products

Do-It-Yourself Devices Personal Fabrication of Custom Electronic Products David Adley Mellis SB Mathematics Massachusetts Institute of Technology, June 2003 MA Interaction Design Interaction Design Institute Ivrea, June 2006 SM Media Arts and Sciences Massachusetts Institute of Technology, September 2011 Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences School of Architecture and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2015 © 2015 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All right reserved. Author: David A. Mellis Program in Media Arts and Sciences August 7, 2015 Certified by: Mitchel Resnick LEGO Papert Professor of Learning Research Program in Media Arts and Sciences Accepted by: Pattie Maes Academic Head Program in Media Arts and Sciences Do-It-Yourself Devices Personal Fabrication of Custom Electronic Products David Adley Mellis Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences School of Architecture and Planning on August 7, 2015 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Abstract Many domains of DIY (do-it-yourself) activity, like knitting and woodworking, offer two kinds of value: the making process itself and using the resulting products in one’s life. With electronics, the sophistication of modern devices makes it difficult to combine these values. Instead, when people make electronics today, they generally use toolkits and other prototyping processes that aren’t well suited to extended use. This dissertation investigates digital fabrication (of both electronic circuit boards and enclosures) as an alternative approach to DIY electronics, one that can support individuals in both making devices and using them in their daily lives. -

The Ultimate C64 Overview Michael Steil, 25Th Chaos Communication Congress 2008

The Ultimate C64 Overview Michael Steil, http://www.pagetable.com/ 25th Chaos Communication Congress 2008 Retrocomputing is cool as never before. People play Look and Feel C64 games in emulators and listen to SID music, but few people know much about the C64 architecture A C64 only needs to be connected to power and a TV and its limitations, and what programming was like set (or monitor) to be fully functional. When turned back then. This paper attempts to give a comprehen- on, it shows a blue-on-blue theme with a startup mes- sive overview of the Commodore 64, including its in- sage and drops into a BASIC interpreter derived from ternals and quirks, making the point that classic Microsoft BASIC. In order to load and save BASIC computer systems aren't all that hard to understand - programs or use third party software, the C64 re- and that programmers today should be more aware of quires mass storage - either a “datasette” cassette the art that programming once used to be. tape drive or a disk drive like the 5.25" Commodore 1541. Commodore History Unless the user really wanted to interact with the BA- SIC interpreter, he would typically only use the BA- Commodore Business Machines was founded in 1962 SIC instructions LOAD, LIST and RUN in order to by Jack Tramiel. The company specialized on elec- access mass storage. LOAD"$",8 followed by LIST tronic calculators, and in 1976, Commodore bought shows the directory of the disk in the drive, and the chip manufacturer MOS Technology and decided LOAD"filename",8 followed by RUN would load and to have Chuck Peddle from MOS evolve their KIM-1 start a program. -

300 Baud Issue 03

#3 Well, well, well! We actually did it and we find ourselves back for another issue. #"6% Its been hard going but it is now complete and in your hands. Once again thanks to everyone that made this possible, the writers in particular who gave up their time and creative efforts. And another thanks to the people who came out of the woodwork between issues to offer VCF-GB REPORT a hand in other ways. All going well we will march on forwards, towards issue four, but AN EXHIBITOR’S PERSPECTIVE honestly, we cant do it without you. Really. MARK WICKENS Going back a bit to last issue, it is worth throwing out a “Congratulations!!!” to Derek, who won the Atomic Robot competition. Well done Derek for walking to the post office and being randomly chosen! From my perspective receiving the post cards, it very was nice seeing stamps from different parts of the world. It seems I can pretty much geek out about anything. Thanks for sharing. Anyway back to this issue. As always we As the cat winks at me from a cushion on the sofa, and Stevie Wonder sings have some things of ‘everything is all right’ I start penning my thoughts on the first ‘official’ Vintage interest to the newbie Computer Festival in the UK, *ever*. Having never quite made it to VCF-E (the and to the hardcore geek. At one end of European VCF held in Munich every year in the Spring) and after my own DEC the spectrum, Gavin Legacy Event in aid of the National Museum of Computing, it seemed appropriate Picknell returns to to show up with my DEC gear at an event geared firmly towards the masses. -

Retromagazine 01 Eng.Pdf

Spring 2020: there’s a scent of change in the air SUMMARY <HIDDE N> Despite the frankly somewhat dark times we live in, this late spring brings many changes in our lives. Perhaps even finally a return to life as we know ◊ MISTER FPGA, one year later… Page 3 it, after the CoViD-19 nightmare. Even within our editorial initiative there ◊ Interview with Francesco Sblendorio Page 7 are no shortage of changes on the horizon. Indeed, many have already started or will soon be under way. ◊ FAST BASIC – a Locomotive Basic Page 14 compiler in CP/M Let's start with the name of your (hopefully) beloved magazine. From this issue the name of the magazine changes to RetroMagazine World. We ◊ Star Watcher Page 17 have been thrifty and modest: we have only added a small word ("World") ◊ Playing infinite lives with your C64 – Page 21 to our historical name, mostly in order to show our new intention to The challenge goes on address the entire international community and no longer only our numerous Italian readers. ◊ Retromath: Secret Codes Page 24 ◊ 3D Graphs with few lines in BASIC Page 27 How do we intend to do this? Well, actually, we already did it last May 2nd, with the release of issue zero of RetroMagazine English, a pilot publication ◊ Japan cronicles: A new Game & Watch? Page 32 entirely in English, dedicated to all the retrocomputing, retrogaming and retrocoding fans scattered all over the planet. These readers have long ◊ How I discovered RPG games on my Page 36 been asking us to bring in a "neutral" language (an official language, TI99/4A understandable to all) for the content and columns that for over two years ◊ KNIGHTMARE SAGA (MSX) Page 42 have been reaching Italian readers. -

Retrocomputer Magazine

Jurassic News Retrocomputing: Buon compleanno tre scuole di Spectrum! pensiero, un solo movimento C R La storia del BASIC A Y 1 Le mostre Torino: Steve Jobs 1955-2011 Bertiolo 2012 Apple Club: il miniBASIC Trento: Era domani Retrocomputer Magazine Anno 7 - Numero 41 - Maggio 2012 Collophon I dati editoriali della rivista Jurassic News Jurassic News Rivista aperiodica di Retrocomputer Jurassic News Coordinatore editoriale: Tullio Nicolussi [Tn] E’ una fanzine dedicata al retro- Redazione: computing nella più ampia accezione del [email protected] termine. Gli articoli trattano in generale dell’informatica a partire dai primi anni Hanno collaborato a questo numero: ‘80 e si spingono fino ...all’altro ieri. Besdelsec [Bs] Lorenzo [L2] La pubblicazione ha carattere Sonicher [Sn] puramente amatoriale e didattico, tutte Salvatore Macomer [Sm] Lorenzo Paolini [Lp] le informazioni sono tratte da materiale Giovanni [jb72] originale dell’epoca o raccolte su Internet. Antonio Tierno Cecilia Botta Normalmente il materiale originale, Moira Bertolini anche se “giurassico” in termini Felice Pescatore informatici, non è privo di restrizioni di Luca Papinutti utilizzo, pertanto non sempre è possibile Damiano Cavicchio Massimo Cellini riportare per intero articoli, foto, schemi, listati, etc…, che non siano esplicitamente Diffusione: liberi da diritti. La rivista viene diffusa in formato PDF via Internet agli utenti E’ possibile che parti del materiale registrati sul sito: pubblicato derivi da siti internet che non sono citati direttamente negli articoli. www.jurassicnews.com. Questo per la difficoltà di attribuzione del Contatti: materiale alla fonte originale; eventuali [email protected] segnalazioni e relative notifiche sono benvenute. Copyright: I marchi citati sono di copyrights La redazione e gli autori degli dei rispettivi proprietari. -

BOULDER DASH CONSTRUCTION KIT Disk Into the Disk Drive, Label Side Up, and Type LOAD" *",8,1 and Press RETURN

Game Designed by First Star Software, Inc, The name's Rockford.™ And diamonds It ain't always easy. You spend half are my game. your life in the diamonds and half your life out of 'em. £ LOTS OF 6 MUMMIES *nKFY So I decided to do some research. Looks like I came to the right place. And I started at the Cairo Museum of Check out these glass cases! Diamond History... Sure they turn into diamonds - but these critters can turn you into mine And f/7/s slimy stuff can multiply into a dust too! fortune-or a fiasco... Woah...Now we're talking diamonds... It appears you have an interest in I'll just jot this down and hop on the diamonds young man... next plane to fame and fortune. ...most young miners do. Thinkin' ... Every successful - and not-so-suc they can get rich quick and the like. cessful - miner has read the ancient Well sometimes you can, but you have miner's handbook. It tells you how you to do your homework. can make it to the top - but read the fine print... ...For instance there is the curse you know - the curse of poor planning, ...Yeah....uhuh...sure...I'm giving that poor concentration, poor minin1 skills. some thought... All will bring overly anxious young miners to the poor house. Are you thinking about that? OBJECTIVE You have two objectives in BOULDER DASH "CONSTRUCTION KIT1? You can either play the pre-saved game provided on the program disk, or construct your own games with the construction kit. -

Chapter 18 Magazines and Newsletters

Chapter 18 Magazines and Newsletters 18.1 ... The Beginning Publication of personal computing articles was initially in electronic magazines such as Popular Electronics, QST and Radio-Electronics. Then came the magazines and newsletters devoted to personal computing and microcomputers. Most of these initial publications were not specific to a particular microprocessor or type of microcomputer. The following are some of the more significant publications. The first publication devoted to personal computing was the Amateur Computer Society ACS Newsletter. The editor was Stephen B. Gray who was also the founder of ACS. The first issue was published in August 1966 and the last in December 1976. It was a bi- monthly directed at anyone interested in building and operating a personal computer. The newsletter was a significant source of information on the design and construction of a computer during the time period it was published. The PCC Newsletter was published by Robert L. Albrecht of the People's Computer Company in California. The first issue was published in October 1972. The first issue cover stated it “is a newspaper... about having fun with computers, learning how to use computers, how to buy a minicomputer for yourself your school and books films and tools of the future.” The newspaper name changed to the People’s Computers with a magazine type of format in May-June 1977. Hal Singer started the Micro-8 Newsletter in September 1974. This was a newsletter published by the Micro-8 Computer Users Group, originally the Mark-8 Group for Mark-8 computer users. Another publication started in 1974, was The Computer Hobbyist newsletter. -

Fifty Years in Home Computing, the Digital Computer and Its Private Use(Er)S

International Journal of Parallel, Emergent and Distributed Systems ISSN: 1744-5760 (Print) 1744-5779 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gpaa20 Fifty years in home computing, the digital computer and its private use(er)s Stefan Höltgen To cite this article: Stefan Höltgen (2020) Fifty years in home computing, the digital computer and its private use(er)s, International Journal of Parallel, Emergent and Distributed Systems, 35:2, 170-184, DOI: 10.1080/17445760.2019.1597085 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/17445760.2019.1597085 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 26 Mar 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 354 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gpaa20 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PARALLEL, EMERGENT AND DISTRIBUTED SYSTEMS 2020, VOL. 35, NO. 2, 170–184 https://doi.org/10.1080/17445760.2019.1597085 Fifty years in home computing, the digital computer and its private use(er)s Stefan Höltgen Department for Musicology and Media Science, Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The following chapter will discuss the relation between home computer his- Received 13 March 2019 tory and computer programming – with a focus on game programming. Accepted 16 March 2019 The nurseries of the early 1980s are the origins of the later computer game KEYWORDS industry and the private use of microcomputers becomes an essential part Homecomputer; computer of the ‘playful’ exploration and emancipation of technology. -

Units of Veritechnology Electronics Corporation

I SNOW Build our new kit picture-in-picture TV with premium stereo sound and ) full-featured remote control. Turn to pages 4 and 5. Units of Veritechnology Electronics Corporation Dear Friends: Your Heathkit Catalog World Famous Manuals Computer tech- The new spring '89 Heathkit catalog 'n tiologv is advancing Included with each kit is one of our laster than ever. And brings a selection of line electronic world famous assenibly manuals to aid • at Heath/Zenith, we products into 'our home. You'll find every step of the way. The re writ- - always keep on top hot ii quality assembled products and ten byuor own technical writers, experts of what's hot and our own electronic kits. in the product lines, who are actively in- ' hat's new. We can' volved in the various stages of building I everything from each newproduct. poerlul business computers to the Clearly written manuals are the ultimate in laptop portables, both result of such involvement. The step-by- Zenith Data Systems and Apple Fine Assembled Products step lot-mat and large pictorials of key Computer. Plus we bring you Many of the assenibledproducts we assembly steps give even the novice printers, software and accessories feature carry another manufacturer's electronic kit builder the tools necessary from a wide variety of big-name name; others are our own. Whether they to succeed. manufacturers. At prices that other carry our name or another name, all computer chains will find hard to must meet the stringent standards of beat. our engineers and undergo the careful If you're into kit building, we testing and evaluation of our quality carr a full line ol fun-to-build controll'( )l &.'x x' Ii 5. -

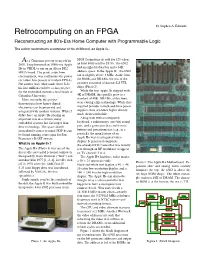

Retrocomputing on an FPGA Reconstructing an 80’S-Era Home Computer with Programmable Logic

by Stephen A. Edwards Retrocomputing on an FPGA Reconstructing an 80’s-Era Home Computer with Programmable Logic The author reconstructs a computer of his childhood, an Apple II+. As a Christmas present to myself in MOS Technology (it sold for $25 when 2007, I implemented an 1980s-era Apple an Intel 8080 sold for $179). The 6502 II+ in VHDL to run on an Altera DE2 had an eight-bit data bus and a 64K FPGA board. The point, aside from address space. In the Apple II+, the 6502 entertainment, was to illustrate the power ran at slightly above 1 MHz. Aside from (or rather, low power) of modern FPGAs. the ROMs and DRAMs, the rest of the Put another way, what made Steve Jobs circuitry consisted of discrete LS TTL his first million could be a class project chips (Photo 2). for the embedded systems class I teach at While the first Apple IIs shipped with Columbia University. 4K of DRAM, this quickly grew to a More seriously, this project standard of 48K. DRAMs, at this time, demonstrates how legacy digital were cutting-edge technology. While they electronics can be preserved and required periodic refresh and three power integrated with modern systems. While I supplies, their six-times higher density didn’t have an Apple II+ playing an made them worthwhile. important role in a system, many Along with with an integrated embedded systems last far longer than keyboard, a rudimentary (one-bit) sound their technology. The space shuttle port, and a game port that could sense immediately comes to mind; PDP-8s can buttons and potentiometers (e.g., in a be found running some signs for San joystick), the main feature of an Francisco’s BART system.