History Andtheory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite!

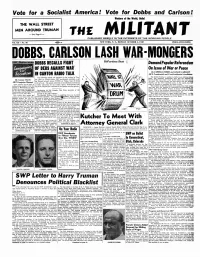

Vote for a Socialist America! Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite! THE WALL STREET MEN AROUND TRUMAN — See Page 4 — THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 4, 1948 Vol. X II -.No. 40 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS, CARLSON LASH WAR <yMONGERS ;$WP flection New* DOBBS RECALLS FI6HT Bp-Partisan Duet flj Demand Popular Referendum OF DEBS AGAINST WAR On Issue o f W ar or Peace By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON IN CANTON RADIO TALK SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates The following speech was broadcast to the workers of Can The United Nations is meeting in Paris in an ominous atmos- phere. The American imperialists have had the audacity to ton, Ohio, by Farrell Dobbs, SWP presidential candidate, over By George Clarke launch another war scare a bare month before the voters go to the Mutual network station WHKK on Friday, Sept. 24 from the polls. The Berlin dispute has been thrown into the Security SWP Campaign Manager 4 :45 to 5 p.m. The speech, delivered on the thirtieth anniversary Council; and the entire capitalist press, at this signal, has cast Grace Carlson got the kind of of Debs’ conviction for his Canton speech, demonstrates how aside all restraint in pounding the drums of war. welcome-home reception when she the SWP continues the traditions of the famous socialist agitator. The insolence of the Wan Street rulers stems from their assur arrived in Minneapolis on Sept. ance that they w ill continue to monopolize the government fo r 21 that was proper and deserving another four years whether Truman or Dewey sits in the White fo r the only woman candidate fo r Introduction by Ted Selander, Ohio State Secretary of the House. -

Call for a Workers and Farmers Government As Only Answer to Wall Street War-Makers Jft

Workers of the World, Unite! SPECIAL SWP CONVENTION ISSUE THE MILITANT __________ PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE __________________ Vol. XII— No. 28 267 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, JULY 12, 1948 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS AND CARLSON ADDRESS NATION IN BROADCASTS FROM SWP CONVENTION Call for a Workers and Farmers Government As Only Answer to Wall Street War-Makers Jft. SWP Candidates Address the Nation Inspiring Five-Day Gathering The Two Opens Presidential Campaign A m e rica s Of Socialist Workers Party By Art Preis James P. Cannon’s Key-Note Speech . NEW YORK, July 6 — Cheering to the echo the choice of Farrell Dobbs and Grace Carlson as first Over the ABC Network on July 1st Trotskyist candidates for U. S. President and Vice* President, the 13th National Convention of the So The following is the keynote speech delivered by James cialist Workers Party sum-® Cannon, National Secretary of the Socialist Workers Party, a propaganda blow been struck to the party’s 13th convention at 11:15 P. M. on July 1, and moiled the American peo in this country for the socialist broadcast over Radio network ABC at that time. ple to join with the SWP cause. That millions of people in a forward march to a Workers heard the SWP call is shown by Comrade Chairman, Delegates and Friends: and Farmers Government and the flood of letters and postcards We meet in National Convention at a t'ime of the gravest socialism. that hit the SWP National Head quarters in the first post-holiday world crisis— a crisis which contains the direct threat of a third Ih' an atmosphere charged with mail deliveries this morning. -

Social Bonds, Sexual Politics, and Political Community on the U.S. Left, 1920S-1940S' Kathleen A

Social Bonds, Sexual Politics, and Political Community on the U.S. Left, 1920s-1940s' Kathleen A. Brown and Elizabeth Faue William Armistead Nelson Collier, a sometime anarchist and poet, self- professed free lover and political revolutionary, inhabited a world on the "lunatic fringe" of the American Left. Between the years 1908 and 1948, he traversed the legitimate and illegitimate boundaries of American radicalism. After escaping commitment to an asylum, Collier lived in several cooperative colonies - Upton Sinclair's Helicon Hall, the Single Tax Colony in Fairhope, Alabama, and April Farm in Pennsylvania. He married (three times legally) andor had sexual relationships with a number of radical women, and traveled the United States and Europe as the Johnny Appleseed of Non-Monogamy. After years of dabbling in anarchism and communism, Collier came to understand himself as a radical individualist. He sought social justice for the proletariat more in the realm of spiritual and sexual life than in material struggle.* Bearded, crude, abrupt and fractious, Collier was hardly the model of twentieth century American radicalism. His lover, Francoise Delisle, later wrote of him, "The most smarting discovery .. was that he was only a dilettante, who remained on the outskirts of the left wing movement, an idler and loafer, flirting with it, in search of amorous affairs, and contributing nothing of value, not even a hard day's work."3 Most historians of the 20th century Left would share Delisle's disdain. Seeking to change society by changing the intimate relations on which it was built, Collier was a compatriot, they would argue, not of William Z. -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

Annual Town Report Harvard, Massachusetts

2016 Annual Town Report Harvard, Massachusetts TOWN OF HARVARD WORCESTER COUNTY DATE OF INCORPORATION: 1732 FORM OF GOVERNMENT: Town Meeting POPULATION: 5,778 – as of January 1, 2016 AREA: 16,500 acres ELEVATION: 608 feet above sea level on Oak Hill MINIMUM BUILDING LOT SIZE: 1.5 acres Building, Electrical, Plumbing Codes and Health Regulations require permits for new buildings and alterations, obtainable at the Selectmen’s Office in Town Hall. TOWN HALL OFFICE HOURS: 8:00 A.M. – 4:30 P.M. Monday - Thursday 8:00 A.M. – 7:00 P.M. second Tuesday of the month SENATORS IN CONGRESS: Elizabeth Warren, Edward Markey REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS, 3rd District: Nicola Tsongas STATE SENATOR, Middlesex and Worcester District: James Eldridge STATE REPRESENTATIVE, 37th Middlesex District: Jennifer Benson QUALIFICATIONS FOR REGISTRATION AS VOTERS: Must be 18 years of age, and a U.S. citizen. Registration at Town Clerk’s Office in Town Hall, Monday through Thursday, 8:00 A.M. – 4:30 P.M., and the second Tuesday of the month until 7:00 P.M. Special voter registration sessions before all town meetings and elections. Absentee voting for all elections. TOWN OF HARVARD FOUNDED JUNE 29, 1732 Set off from Groton, Lancaster, Stow, by petitions to the General Court. Incorporators: Simon Stone, Groton, Thomas Wheeler Stow and Hezekiah Willard, Lancaster. The name Harvard was inserted in the engrossed bill in the handwriting of Josiah Willard, the Secretary of State. This was the custom when neither the Governor nor petitioners had suggested a name for the new town. SPECIAL THANKS – 2016 ANNUAL TOWN REPORT All photos in the report are courtesy of the Harvard Press. -

Bass Seeks Presidency of CIO Rubber Workers

Workers of the World, Unite! EIGHT YEARS AFTER TROTSKY’S DEATH (See Page 2) THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Vol. X II - No. 34 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, AUGUST 23, 1948 PRICE: FIVE CENTS The Wounded Killer Grace Carlson MINNEAPOLIS CIO Addresses Ford ASKS RESTORATION Union Meeting OF RIGHTS OF 18 DETROIT, Aug. 15—Dr. Grace Carlson, Vice-Presidential candidate of the Socialist Workers Party, opened her Michigan campaign, by addressing the largest section of the largest Local Stalinist-Ruled Council Forced to Reverse Union in the world, the Motor®the Stalinist Party — to its eter Building section of Ford Local nal disgrace and shame — sup Union 600 of the CIO auto union. ported the government drive Wartime Stand Against Smith Act Victims The meeting was attended by 200 against the Socialist Workers of the best militants employed in Party leaders and the fighting MINNEAPOLIS, Aug. 16—The Hennepin County CIO Council here has adopted a the Motor Truckdrivers Union of Minnea resolution demanding that the Truman administration restore the civil rights of the 18 Socialist Building. “ The polis and the Northwest area. Workers Party and Minneapolis Drivers Local 5 44-CIO leaders imprisoned during the war under Socialist Work Now the very same act is being the infamous Smith “ Gag” Act.®---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ers Party can utilized against the Stalinist time of the famous Minneapolis didates fig h t This resolution, adopted Aug. cialist Workers Party members Party.” Labor Trial and the subsequent in 1941.” 365 days in the Dr. Carlson read from The 11, completely reverses the posi tion of the CIO Council at the federal imprisonment of the 18 In addition to demanding the year in the M ilitant the recent appeal for Trotskyists. -

Chicago's Torture Machine and Reparations Palestine

Burma: War vs. the People w Behind Detroit’s Labor History #213 • JULY/AUGUST 2021 • $5 Chicago’s Torture Machine and Reparations w AISLINN PULLEY w MARK CLEMENTS w JOEY MOGUL w LINDA LOEW Palestine — Then and Now w MALIK MIAH w MOSHE MACHOVER w DAVID FINKEL w MERRY MAISEL w DON B. GREENSPON A Letter from the Editors: Infrastructure: Who Needs It? “INFRASTRUCTURE” IS ALL the rage, and not only just now. Trump talked about it, president Obama promised it, and so have administrations going back to the 1980s. Amidst the talk, the United States’ roads and bridges are crumbling, water and sanitation systems faltering, public health services left in a condition that’s only been fully exposed in the coronavirus pandemic, and rapid transit and high-speed internet access in much of the country inferior to what’s available in the rural interior of China. A combination of circumstances have changed the discussion. The objective realities include the pandemic; its devastating economic impacts most heavily on Black, brown and women’s employment; the necessity of rapid conversion to renewable energy, now clear even to much of capital — and yes, the pressures of deepening competition and rivalry with China. The obvious immediate political factors are the defeat of Trump and the ascendance of the Democrats to narrow Congressional and Senate majorities. It became clear, however, that there would be no serious results, they might well be electorally dead in 2022 Republican support for anything resembling Biden’s and beyond. That pressure, along with the party’s left wing, infrastructure program — even after he’d stripped several put some backbone into the administration’s posture hundred billion dollars and scrapped raising the corporate although the “progressive” forces certainly don’t control tax rate to pay for it. -

New York News Delivery Strikers Check Union-Busting Assault

READ "The History Of American Tr — SEE PAGE 6 — the PUBLISHEDMILITANT IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE VOL. IX—No. 29 NEW YORK, N. Y„ SATURDAY, JULY 21, 1945 PRICE: FIVE CENTS Trotskyist Runs British Despots For Parliament New York News Delivery Strikers In Nigeria Ban In Chile Election By Henriquez SANTIAGO, Chile, July 4 Check Union-Busting Assault Native Papers (By Airmail) — The Partido Obrero Revolucionario, Chilean Special to The Militant section of the Fourth Interna Congressional Lynchers at Work tional, ran a candidate in last COMPEL WLB TO ISSUE ORDER LONDON, July 16 — Two Negro-edited newspapers in week’s1 by-election for a parlia Nigeria which have espoused the cause of the terribly oppressed mentary deputy to represent the ON PUBLISHERS TO ARBITRATE and exploited population of that country hav^ been suppressed city of Concepcion, third largest by order of Governor Richards, according to cabled advices re of the country and second larg BULLETIN ceived here. est in industry. NEW YORK — A general membership meeting of the Nigeria is a British crown colony in Equatorial Africa, one of The POR delegates at the elec Newspaper Deliverers Union here, held just before The Militant the largest and wealthiest of British possessions, with a population tion tables counted 400 votes cast of over 21,000,000. I t is ruled through the Colonial Office in London. fo r our candidate, but the offi went to press, voted to end the 18-day strike halting circulation Suppression of the two papers, the West African Pilot and cial figures gave us 321 votes. -

Iowa and Some Iowans

Iowa and Some Iowans Fourth Edition, 1996 IOWA AND SOME IOWANS A Bibliography for Schools and Libraries Edited by Betty Jo Buckingham with assistance from Lucille Lettow, Pam Pilcher, and Nancy Haigh o Fourth Edition Iowa Department of Education and the Iowa Educational Media Association 1996 State of Iowa DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Grimes State Office Building Des Moines, Iowa 50319-0146 STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Corine A. Hadley, President, Newton C. W. Callison, Burlington, Vice President Susan J. Clouser, Johnston Gregory A. Forristall, Macedonia Sally J. Frudden, Charles City Charlene R. Fulton, Cherokee Gregory D. McClain, Cedar Falls Gene E. Vincent, Carroll ADMINISTRATION Ted Stilwill, Director and Executive Officer of the State Board of Education Dwight R. Carlson, Assistant to Director Gail Sullivan, Chief of Policy and Planning Division of Elementary and Secondary Education Judy Jeffrey, Administrator Debra Van Gorp, Chief, Bureau of Administration, Instruction and School Improvement Lory Nels Johnson, Consultant, English Language Arts/Reading Betty Jo Buckingham, Consultant, Educational Media, Retired Division of Library Services Sharman Smith, Administrator Nancy Haigh It is the policy of the Iowa Department of Education not to discriminate on the basis of race, religion, national origin, sex, age, or disability. The Department provides civil rights technical assistance to public school districts, nonpublic schools, area education agencies and community colleges to help them eliminate discrimination in their educational programs, activities, or employment. For assistance, contact the Bureau of School Administration and Accreditation, Iowa Department of Education. Printing funded in part by the Iowa Educational Media Association and by LSCA, Title I. ii PREFACE Developing understanding and appreciation of the history, the natural heritage, the tradition, the literature and the art of Iowa should be one of the goals of school and libraries in the state. -

A Conversation with Myra Tanner Weiss

American Trotskyism’s ‘Anarchobolshevik’ A Conversation with Myra Tanner Weiss Myra Tanner Weiss, a prominent figure in the American Trotskyist movement through the 1940s and 50s, died in a nursing home in Indio, California on 13 September 1997 at the age of eighty. She had been the organizer of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) five-branch Los Angeles local for a decade, a member of the party’s National Committee from 1944 to 1963, a three-time SWP candidate for vice-president of the United States, and, for many years, served as the only female full member of its Political Committee (PC). In her 20 September 1997 obituary the New York Times described her a “fiery speaker” who: “cut a stylish figure in leftist circles—a small, attractive woman who was always immaculately turned out, generally in a well-cut suit of lush material run up by her husband’s tailoring family.” Myra joined the Trotskyist movement 1935, while at university in Salt Lake City. She soon moved to California where she participated in a union organizing drive to sign up agricultural and cannery workers. In 1942 she married Murry Weiss. The young couple, who were among the most dynamic people in the SWP at the time, ran the party’s Los Angeles local during most of the 1940s. Under their leadership the LA branch was not only the liveliest, but also, by the end of the decade, the largest. It was also the party’s chief source of young recruits. In addition to serving as Los Angeles district organizer, Myra was also the group’s main public figure, running for mayor in both 1945 and 1949. -

October 2020

June 2018 Upcoming Virtual Programs at the National Archives October 2020 October is American Inside This Issue Archives Month and in celebration the OCTOBER VIRTUAL 1 National Archives PROGRAMS has an extensive line HIDDEN TREASURES 2-5 -up of virtual public FROM THE STACKS programs. A full list can be found here. EDUCATION 6-7 Below are two that RESOURCES are intended for COVID-19 7 multiple audiences INFORMATION and are scheduled according to Eastern Daylight Time. On Saturday, Upcoming Events October 10 at Unless noted, all events 3:00 p.m. EDT, the are held at the National Archives National Archives will host The Write 400 W. Pershing Road Stuff: Records on Women’s Battle for the Ballot. This panel discussion will feature authors Kansas City, MO 64108 Winifred Conkling, Marjorie Spruill, and Elaine Weiss who will discuss their work on research and writing in regard to women’s rights, suffrage and the movement that has OCT. 10 - 3:00 P.M. EDT followed. Registration is required for this free event. VIRTUALLY VIA LIVE- STREAM: THE WRITE STUFF On Saturday, October 17 at 8:00 p.m. EDT, the National Archives will host a Virtual PANEL DISCUSSION Pajama Party with special guest author Sharon Robinson, daughter of civil rights leader and professional athlete Jackie Robinson. Robinson will discuss her book The Hero Two OCT. 17 - 8:00 P.M. EDT Doors Down. VIRTUALLY VIA LIVE- STREAM: VIRTUAL PAJAMA This online event PARTY is geared toward children aged 8- NOTE: All in-person 12 years-old. The public events at focus will be on National Archives Jackie Robinson’s baseball career facilities nationwide and work as a are cancelled until civil rights leader. -

James P. Cannon Bio-Bibliographical Sketch

Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet James P. Cannon Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: • Basic biographical data • Biographical sketch • Selective bibliography • Notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: James P. Cannon Other names (by-names, pseud., etc.): John Battle ; C. ; James Patrick Cannon ; Jim Can non ; Cook ; Dawson ; Dzh. P. Kannon ; Legrand ; Martel ; Martin ; Jim McGee ; Walter Date and place of birth: February 11, 1890, Rosedale, Ka. (USA) Date and place of death: August 21, 1974, Los Angeles, Cal. (USA) Nationality: USA Occupations, careers, etc.: Journalist, political activist, party leader, writer and editor Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1928 - 1974 (lifelong Trotskyist) Biographical sketch James P. Cannon was an outstanding example for American labour radicalism, a life-long devoted and unwaver ing socialist and internationalist, a co-founder of both the communist (in 1919/20) and the Trotskyist (in 1928/ 29) movement in the United States, the founder and long-time leader of the American Socialist Workers Party (SWP) and its predecessors as well as one of the most influential figures in the Trotskyist Fourth International (FI) during the first two decades of its existence. However, his features in the annals of Trotskyism are far away from being homogeneous, and it is a very truism that a man like Cannon must almost inevitably have caused much controversy. Undoubtedly being America's foremost Trotskyist and vigorously having coined the SWP, he on the one hand has been continuously worshipped and often monopolized by various epigones whereas on the other hand Trotskyist and ex-Trotskyist dissidents have considered him an embodiment of petrified orthodoxy or workerism or ultra-Leninist factionalism.