A Conversation with Myra Tanner Weiss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite!

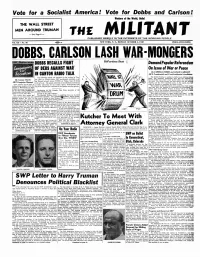

Vote for a Socialist America! Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite! THE WALL STREET MEN AROUND TRUMAN — See Page 4 — THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 4, 1948 Vol. X II -.No. 40 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS, CARLSON LASH WAR <yMONGERS ;$WP flection New* DOBBS RECALLS FI6HT Bp-Partisan Duet flj Demand Popular Referendum OF DEBS AGAINST WAR On Issue o f W ar or Peace By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON IN CANTON RADIO TALK SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates The following speech was broadcast to the workers of Can The United Nations is meeting in Paris in an ominous atmos- phere. The American imperialists have had the audacity to ton, Ohio, by Farrell Dobbs, SWP presidential candidate, over By George Clarke launch another war scare a bare month before the voters go to the Mutual network station WHKK on Friday, Sept. 24 from the polls. The Berlin dispute has been thrown into the Security SWP Campaign Manager 4 :45 to 5 p.m. The speech, delivered on the thirtieth anniversary Council; and the entire capitalist press, at this signal, has cast Grace Carlson got the kind of of Debs’ conviction for his Canton speech, demonstrates how aside all restraint in pounding the drums of war. welcome-home reception when she the SWP continues the traditions of the famous socialist agitator. The insolence of the Wan Street rulers stems from their assur arrived in Minneapolis on Sept. ance that they w ill continue to monopolize the government fo r 21 that was proper and deserving another four years whether Truman or Dewey sits in the White fo r the only woman candidate fo r Introduction by Ted Selander, Ohio State Secretary of the House. -

Call for a Workers and Farmers Government As Only Answer to Wall Street War-Makers Jft

Workers of the World, Unite! SPECIAL SWP CONVENTION ISSUE THE MILITANT __________ PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE __________________ Vol. XII— No. 28 267 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, JULY 12, 1948 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS AND CARLSON ADDRESS NATION IN BROADCASTS FROM SWP CONVENTION Call for a Workers and Farmers Government As Only Answer to Wall Street War-Makers Jft. SWP Candidates Address the Nation Inspiring Five-Day Gathering The Two Opens Presidential Campaign A m e rica s Of Socialist Workers Party By Art Preis James P. Cannon’s Key-Note Speech . NEW YORK, July 6 — Cheering to the echo the choice of Farrell Dobbs and Grace Carlson as first Over the ABC Network on July 1st Trotskyist candidates for U. S. President and Vice* President, the 13th National Convention of the So The following is the keynote speech delivered by James cialist Workers Party sum-® Cannon, National Secretary of the Socialist Workers Party, a propaganda blow been struck to the party’s 13th convention at 11:15 P. M. on July 1, and moiled the American peo in this country for the socialist broadcast over Radio network ABC at that time. ple to join with the SWP cause. That millions of people in a forward march to a Workers heard the SWP call is shown by Comrade Chairman, Delegates and Friends: and Farmers Government and the flood of letters and postcards We meet in National Convention at a t'ime of the gravest socialism. that hit the SWP National Head quarters in the first post-holiday world crisis— a crisis which contains the direct threat of a third Ih' an atmosphere charged with mail deliveries this morning. -

Vote for Working Class Candidates L Vote for Dobbs and Carlson

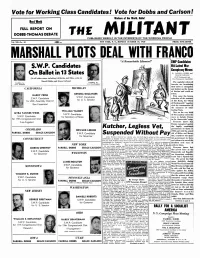

Vote fo r Working Class Candidates l Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers off the World, Unite! Hext Week FULL REPORT ON DOBBS-THOMAS DEBATE the M I liTANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Voi. XII-No. 42 267 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 18, 1948 PRICE: FIVE CENTS MARSHALL PLOTS DEAL WITH FRANCO “A Remarkable Likeness!” SWP Candidates S.W.P. Candidates Hit Latest War Conspiracy Moves On Ballot in 13 States By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON (In all other states including California and Ohio, write in SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates' Farrell Dobbs and Grace Carlson) The capitalist rulers ot Candidate for Candidate for U. S. President U. S. Vice-President America are broadening their drive to strengthen CALIFORNIA MICHIGAN and bolster up the forces of fascism and world re GENORA DOLLINGER action. HARRY PRESS First came the brazen S.W.P. Candidate S.W.P. Candidate reduction of the sentence for U. S. Senator for 20th Assembly District of Use Koch, the “ Beast of Buchenwald,” together (San Francisco) with the commutation of the sentences of other leading Nazis. WILLIAM YANCEY MYRA TANNER WEISS Now on the very heels S.W.P. Candidate of this scandal, comes the S.W.P. Candidate for Secretary of State move to include Franco for 19th Congressional Dist. in the ‘democratic’ camp. (Los Angeles) Everyone knows that Franco conspired against Kutcher, Legless Vet, the legally constituted COLORADO government of Spain in HOWARD LERNER 1936 and with the armed FARRELL DOBBS GRACE CARLSON S.W.P. -

The Old Mole and New Mole Files!)

1 “LENINST BOOMERS” BUILD “THE FIFTH INTERNATIONAL”: THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE LABOR COMMITTEE (PLUS THE OLD MOLE AND NEW MOLE FILES!) Introduction: This series of FactNet posts provides the most detailed look at the early history of the NCLC from LaRouche‟s leaving the SWP in late 1965 to the major faction fight inside the organization in 1971. The files focus most on the early NCLC in two key cities, New York and Philadelphia. However there is some mention of the NCLC group in Baltimore as well as a detailed picture of the early European organization. As part of the research, LaRouche Planet includes two detailed series of posts by Hylozoic Hedgehog (dubbed “the Old Mole Files” and “the New Mole Files”) based on archival research. Much of the discussion involves the proto-LaRouche grouping and its role in SDS, the Columbia Strike, and the New York Teachers Strike in New York as well as the group‟s activity in Philadelphia. Finally, this series of posts can also be read as a continuation of the story of LaRouche and the NCLC begun by the “New Study” also posted on LaRouche Planet which covers LaRouche‟s history from his early years in New Hampshire and Massachusetts to his relocating to New York City in the early 1950s and his activity inside the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party (SWP) until he left the SWP in late 1965. WAYBACK to 1966: How it all began The Free University and CIPA: Origins of the SDS Labor Committees. (More notes from the archives) ―For two years, beginning during the Summer of 1966; the Marcus class at a ramshackle New York Free School premises on New York City's 14th Street was the motor for the growth of a tiny group, the hard core of the future Labor Committees.‖ -- From: The Conceptual History of the Labor Committees by L. -

Support the Socialist Alternative in 1992!

• AUSTRALIA $2.00 • BELGIUM BF60 • CANADA $2.00 • FRANCE FF1 0 • ICELAND Kr150 • NEW ZEALAND $2.50 • SWEDEN Kr1 0 • UK £1.00 • U.S. $1 .50 INSIDE Socialist candidate arrested at Peoria Caterpillar rally THE - PAGE 2 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 56/ NO. 14 April 10. 1992 Defend Support the socialist abortion alternative in 1992! rights! Tens of thousands of supporters of abor Warren and DeBates campaign against tion rights will be marching in the streets of Washington. D.C.. April 5. This demonstra tion will be an important countermobilization two parties of war, racism, depression to the unrelenting attacks by the government BY GREG McCARTAN WASHINGTON. D.C. - The Socialist EDITORIAL Workers Party candidates for U.S. president and vice-president. James Warren and Es and right-wing forces against a woman's telle DeBates, kicked off their campaign at right to choose. a national press conference here March 31. The Jan. 22, 1973, Supreme Court de The two candidates said they will join c ision legalizing abortion was a historic victory for the rights of women. Be fore supporters across the country for the next the Roe v. Wade decree abortion was ille eight months campaigning to present a so cialist alternative, raise an internationalist gal in most states. Thousands of women and working-class voice, and build the fight were made to bear children against their against the increasingly reactionary course will or forced into an illegal and danger ous back-alley abortion. of the two parties of big business - the Democrats and Republicans. -

Convert JPG to PDF Online

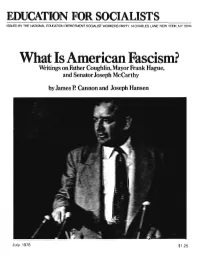

EDUCATION FOR SOCIALISTS ISSUED BY THE NAllONAL EDlJCATION DEPARTMENT SOClAUSf WORKERS PARTY 14 Q-iAALES LANE NEW YORK, NY 10014 What Is American Fascism? Writings on Father Coughlin, Mayor Frank Hague, and SenatorJoseph McCarthy by James RCannon and Joseph Hansen July 1976 $1.25 Contents Introductory Note. by Fred Feldman 3 Section One: Father Coughlin, Fascist Demagogue, by Joseph Hansen 4 Section Two; Mayor Frank Hague of Jersey City, New ,Jersey 13 I. Boss Hague's Police Kidnap Norman Thomas (May 7, 1938, Socialist Appeal) 13 2. Hague's Rule Still Awaits Real Challenge Free Speech Fight Imperative (May 11, 1938, Socialist Appeal) 14 3. Hague Frustrates Meeting Plan-CIG Must Take Lead in Struggle (June 4, 1938, Socialist Appeal) 15 4. How Hague Rules (abridged), by James Raleigh (June 4 and June 11, 1938, Socialist Appeal) 16 5. Jersey City: Lesson and Warning, by James P. Cannon (July 9, 1938. Socialist Appeal) 18 6. Leon Trotsky on Hague: Excerpts from a June 7, 1938, Discussion 19 Section Three: McCarthyism 22 1. McCarthyism: An Editorial (Janul:IrY 18, 1954, Militant) 22 2. Fascism and the Workers' Movement, by James P. Cannon (March 15·April 26, 1954, Militants) 24 3. Draft Resolution on the Political Situation in America (excerpt) (SWP DisclUJsion Bulletin A-20 in 1954) 3;) 4. McCarthy-A "Bourgeois Democrat"? A Reply to Vern and Ryan, by Joseph Hansen (SWP Discussion Bulletin A-25 in 1954) 40 COVER: Senator Joseph R. McCarthy of Wisconsin risl'S to speak at the Army·McCarthy Senate hearings of Spring 1954. Introductory Note The end of the post-World-War.lI economic boom marked American claes struggle and appealing to American an historic turning point for U.S. -

Social Bonds, Sexual Politics, and Political Community on the U.S. Left, 1920S-1940S' Kathleen A

Social Bonds, Sexual Politics, and Political Community on the U.S. Left, 1920s-1940s' Kathleen A. Brown and Elizabeth Faue William Armistead Nelson Collier, a sometime anarchist and poet, self- professed free lover and political revolutionary, inhabited a world on the "lunatic fringe" of the American Left. Between the years 1908 and 1948, he traversed the legitimate and illegitimate boundaries of American radicalism. After escaping commitment to an asylum, Collier lived in several cooperative colonies - Upton Sinclair's Helicon Hall, the Single Tax Colony in Fairhope, Alabama, and April Farm in Pennsylvania. He married (three times legally) andor had sexual relationships with a number of radical women, and traveled the United States and Europe as the Johnny Appleseed of Non-Monogamy. After years of dabbling in anarchism and communism, Collier came to understand himself as a radical individualist. He sought social justice for the proletariat more in the realm of spiritual and sexual life than in material struggle.* Bearded, crude, abrupt and fractious, Collier was hardly the model of twentieth century American radicalism. His lover, Francoise Delisle, later wrote of him, "The most smarting discovery .. was that he was only a dilettante, who remained on the outskirts of the left wing movement, an idler and loafer, flirting with it, in search of amorous affairs, and contributing nothing of value, not even a hard day's work."3 Most historians of the 20th century Left would share Delisle's disdain. Seeking to change society by changing the intimate relations on which it was built, Collier was a compatriot, they would argue, not of William Z. -

History Andtheory

chapter 7 History and Theory Bryan Palmer and Paul Le Blanc Articles throughout the various sections of these volumes are steeped in ‘his- tory and theory’. Some of what is presented here could have been included in previous chapters. For example, Grace Carlson’s critique of racist ideology and William Gorman’s study of W.E.B. Du Bois are related to materials in chapters dealing with racism and anti-racism, Myra Tanner Weiss’s critique of Sternberg grew out of the factional struggle in the Fourth International, Joyce Cowley’s article on the history of women who fought for the right to vote could be placed with other ‘new stirrings’ materials, etc. In the same vein, various contributions in chapters throughout these volumes could be legitimately placed here. The Trotskyist movement was like that – history and theory infused its origins as Trotsky and many others throughout the world grappled with what had gone wrong with ‘the revolution betrayed’. With the founding of the Fourth Inter- national and its American section, the Socialist Workers Party, discussions of history and theory were never separable from political discussions of the cur- rent time and prescriptions for the future. At the same time, there is something to be said for highlighting the sus- tained attention given to matters of history and theory in the US Trotskyist movement – particularly the breadth and diversity represented here. For as the premier capitalist nation in a global system ordered by an accumulative regime driven by the quest for profit, the United States exhibited trends in its develop- ment that could be discerned throughout the advanced political economies of the world. -

Ursula Mctaggart

RADICALISM IN AMERICA’S “INDUSTRIAL JUNGLE”: METAPHORS OF THE PRIMITIVE AND THE INDUSTRIAL IN ACTIVIST TEXTS Ursula McTaggart Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy In the Departments of English and American Studies Indiana University June 2008 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Purnima Bose, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ Margo Crawford, Co-Chairperson ________________________________ DeWitt Kilgore ________________________________ Robert Terrill June 18, 2008 ii © 2008 Ursula McTaggart ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A host of people have helped make this dissertation possible. My primary thanks go to Purnima Bose and Margo Crawford, who directed the project, offering constant support and invaluable advice. They have been mentors as well as friends throughout this process. Margo’s enthusiasm and brilliant ideas have buoyed my excitement and confidence about the project, while Purnima’s detailed, pragmatic advice has kept it historically grounded, well documented, and on time! Readers De Witt Kilgore and Robert Terrill also provided insight and commentary that have helped shape the final product. In addition, Purnima Bose’s dissertation group of fellow graduate students Anne Delgado, Chia-Li Kao, Laila Amine, and Karen Dillon has stimulated and refined my thinking along the way. Anne, Chia-Li, Laila, and Karen have devoted their own valuable time to reading drafts and making comments even in the midst of their own dissertation work. This dissertation has also been dependent on the activist work of the Black Panther Party, the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, the International Socialists, the Socialist Workers Party, and the diverse field of contemporary anarchists. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS 29881 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS NATIONAL HISPANIC HERITAGE Troducing Hispanic Artists and Covering Top "This May Well Be the Case

September 19, 1977 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 29881 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS NATIONAL HISPANIC HERITAGE troducing Hispanic artists and covering top "This may well be the case. But what 1s WEEK IN CONNECTICUT ics of national interest. at stake for the nation is not the adequacy We trust that we can count on your sup of current profits by business standards-it port both at the Capitol and with your con is rather the rate of drllling and production. stituency here in Connecticut. As a re "Even if proposed pricing structures pro HON. WILLIAM R. COTTER vided for sufficient profit, is the price struc OF CONNECTICUT source, we know your office is invaluable to us; and 1! we can be o! any assistance to ture adequate to generate the level of cash IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES you, in terms o! disseminating information, fiow necessary to mount and sustain the drilling effort required to meet the planned Monday, September 19, 1977 please don't hesitate to contact our office. Sincerely, 1985 oil and gas production goals? We con Mr. COTTER. Mr. Speaker, September FRANK MARRERO, clude ... that it is not, and that 1985 na 11 through 17 was National Hispanic Executive Producer, Project Officer. tional oil and gas production will be as much as five million barrels a day below the NEP Heritage Week, an event that recognized goal." the important role of Hispanic-Ameri They said $699 blllion in 1976 prices must cans in our Nation's life. Connecticut, be invested to fulfill production and con where the Hispanic community numbers UNITED STATES-MORE OIL AND servation targets o! NEP. -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

Bob· Chester: Trotskyist Leader & Educator by Ed Harris American Workers Party, Led by A.J

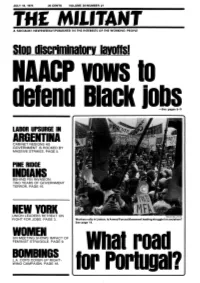

JULY 18, 1975 25 CENTS VOLUME 39/NUMBER 27 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE SIOD discriminatory IBVOIIS! LABOR UPSURGE IN ARGENTINA CABINET RESIGNS AS GOVERNMENT IS ROCKED BY MASSIVE STRIKES. PAGE 5. PINE RIDGE I IS BEHIND FBI INVASION: TWO YEARS OF GOVERNMENT TERROR .. PAGE 16. lEW YORK UNION LEADERS RETREAT ON Militant/Mary Scully FIGHT FOR JOBS. PAGE 3. Workers rally in Lisbon. Is Armed Forces Movement leading struggle for socialism? See page 14. WOMEN UN MEETING SHOWS IMPACT OF FEMINIST STRUGGLE. PAGE 9. liNGS. L.A. COPS COVER UP RIGHT WING CAMPAIGN. PAGE 18. 7II In Brief THIS UNCOMMON CAUSE: The Militant has been reporting front of Japan; and if Japan were directly exposed and WEEK'S how Common Cause chief John Gardner has been going to threatened," Helms said, "her intricate economy bat for the two-party system. The Washington Star recently interwoven so closely with the needs and stability ·of the MILITANT asked him if he didn't think that this was a strange cause Western economies-would collapse." for the so-called People's Lobby to embrace "when many 3 Union leaders retreat voters are expressing no confidence in either the Democratic GAY RIGHTS GAIN: The U.S. Civil Service Commission from jobs fight or Republican parties." The question referred to the has backed off from its policy of excluding homosexuals 4 AFSCME ends Pa. strike Common Cause-promoted public election financing law, f~om government jobs. Newly issued guidelines state that with few gains · which provides tax money to the Democrats and Republi court.decisions and injunctions require "the same standard cans, and excludes smaller parties.