The Old Mole and New Mole Files!)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 7, Number 18, May 13, 1980

Executive Intelligence Review May 13. 1980 $10.00 Europe resists Iran caper manipulation Why Secretary of State Cyrus Vance resigned The wreckage of the Carter administration The Aquarian Conspiracy's road to George Orwell's 1984 [THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK] Editor-in-chief: Daniel Sneider Associate Editor: Robyn Quijano Managing Editors: Kathy Stevens, Vin Berg Art Director: Deborah Asch Circulation Manager: Lana Wolfe Contributing Editors: From the Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., Criton Zoakos, Nora Hamerman, Editor-in-Chief Christopher White, Costas Kalimtgis, Uwe Parpart, Nancy Spannaus INTELLIGENCE DIRECTORS: Africa: Douglas DeGroot Asia: Daniel Sneider Counterintelligence: Jeffrey Steinberg Economics: David Goldman Energy: William Engdahl and Marsha Freeman Europe: Vivian Zoakos Latin America: Dennis Small Law: Felice Merritt I n the early sixties the u.s. space exploration effort captured the Middle East: Robert Dreyfuss imagination of the population, children dreamed of being astronauts Military Strategy: Susan Welsh and scientists, and the future of the nation and the individual family Science and Technology: Morris Levitt was defined by the need for progress and an advanced education for Soviet Sector: Rachel Douglas all the nation's youth. United States: Konstantin George Today an entire generation of youth is addicted to drugs and rock United Nations: Nancy Coker music, and environmentalists, yoga freaks, transcendental medita INTERNATIONAL BUREAUS: tionists and biorhythm kooks consult their horiscope to determine the Bogota: Carlos Cota Meza future. Bonn: George Gregory And so do many of our elected officials. and Thierry LeMarc Brussels: Christine Juarez Governors take drugs and meditate, mayors are flagranthomosex Chicago: Mitchell Hirsch uals, presidents believe in UFOs, and one U.S. -

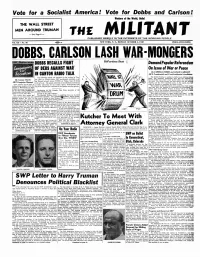

Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite!

Vote for a Socialist America! Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite! THE WALL STREET MEN AROUND TRUMAN — See Page 4 — THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 4, 1948 Vol. X II -.No. 40 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS, CARLSON LASH WAR <yMONGERS ;$WP flection New* DOBBS RECALLS FI6HT Bp-Partisan Duet flj Demand Popular Referendum OF DEBS AGAINST WAR On Issue o f W ar or Peace By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON IN CANTON RADIO TALK SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates The following speech was broadcast to the workers of Can The United Nations is meeting in Paris in an ominous atmos- phere. The American imperialists have had the audacity to ton, Ohio, by Farrell Dobbs, SWP presidential candidate, over By George Clarke launch another war scare a bare month before the voters go to the Mutual network station WHKK on Friday, Sept. 24 from the polls. The Berlin dispute has been thrown into the Security SWP Campaign Manager 4 :45 to 5 p.m. The speech, delivered on the thirtieth anniversary Council; and the entire capitalist press, at this signal, has cast Grace Carlson got the kind of of Debs’ conviction for his Canton speech, demonstrates how aside all restraint in pounding the drums of war. welcome-home reception when she the SWP continues the traditions of the famous socialist agitator. The insolence of the Wan Street rulers stems from their assur arrived in Minneapolis on Sept. ance that they w ill continue to monopolize the government fo r 21 that was proper and deserving another four years whether Truman or Dewey sits in the White fo r the only woman candidate fo r Introduction by Ted Selander, Ohio State Secretary of the House. -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 13, Number 20, May 16, 1986

Can LaRouche Put Don Regan . Behind Bars? READ DOPE, INC. AND JUDGE THE EVIDENCE FOR YOURSELF! ' The classic combat manual of the War on Drugs SECOND EDITION DOPE, INC. Boston Bankers and Soviet Commissars Now available from Caucus Distributors, Inc. P.o. Box 20550 Columbus Circle Station New York, N.Y. 10023 $14.95 plus $1.50 postage and handling for first copy, $.50 each additional copy. Visa or Mastercharge accepted. Founder and Contributing Editor: Lvndon H. LaRouche. Jr. Editor-in-chief: CrilOn Zoakos Editor: Nora Hamerman Managing Editors: Vin Berg and Susan Welsh Contributing Editors: Uwe Parpart-Henke. Nancy Spannaus. Webster Tarpley. Christopher White. Warren Hamerman. From the Editor William Wertz. Gerald Rose. Mel Klenetsky. Antony Papert. Allen Salisbury Science and Technology: Carol White Special Services: Richard Freeman Advertising Director: Joseph Cohen Director of Press Services: Christina Huth F or several weeks, EIR's centerfold (pages 36-37) has been devot INTELLIGENCE DIRECTORS: Africa: Douglas DeGroot. Mary Lalevee ed to a graphic display or strategic map that highlights one of our Agriculture: Marcia Merry major stories, or gives an overview of news developments. This Asia: Linda de Hovos Counterintelligence: Jeffrey Steinberg. week's centerfold sets the safety standards of the Western nuclear Paul Goldstein energy industry (under renewed assault, ironically, from the Soviets' Economics: David Goldman European Economics: William Engdahl. "Green" and "peacenik" friends), against the obsolete technologies Laurent Murawiec used in the Soviet Union. The top nuclear-safety experts were inter Europe: Vivian Freyre Zoakos Ibero-America: Robyn Quijano. Dennis Small viewed for our exclusive coverage of the Chernobyldisaster (starting Law: Edward SpanTlflus page 34). -

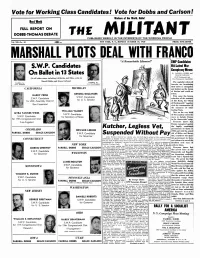

Vote for Working Class Candidates L Vote for Dobbs and Carlson

Vote fo r Working Class Candidates l Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers off the World, Unite! Hext Week FULL REPORT ON DOBBS-THOMAS DEBATE the M I liTANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Voi. XII-No. 42 267 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 18, 1948 PRICE: FIVE CENTS MARSHALL PLOTS DEAL WITH FRANCO “A Remarkable Likeness!” SWP Candidates S.W.P. Candidates Hit Latest War Conspiracy Moves On Ballot in 13 States By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON (In all other states including California and Ohio, write in SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates' Farrell Dobbs and Grace Carlson) The capitalist rulers ot Candidate for Candidate for U. S. President U. S. Vice-President America are broadening their drive to strengthen CALIFORNIA MICHIGAN and bolster up the forces of fascism and world re GENORA DOLLINGER action. HARRY PRESS First came the brazen S.W.P. Candidate S.W.P. Candidate reduction of the sentence for U. S. Senator for 20th Assembly District of Use Koch, the “ Beast of Buchenwald,” together (San Francisco) with the commutation of the sentences of other leading Nazis. WILLIAM YANCEY MYRA TANNER WEISS Now on the very heels S.W.P. Candidate of this scandal, comes the S.W.P. Candidate for Secretary of State move to include Franco for 19th Congressional Dist. in the ‘democratic’ camp. (Los Angeles) Everyone knows that Franco conspired against Kutcher, Legless Vet, the legally constituted COLORADO government of Spain in HOWARD LERNER 1936 and with the armed FARRELL DOBBS GRACE CARLSON S.W.P. -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 19, Number 38, September

fast track to rule by the big banks EIR Special Report, May 1991 Auschwitz below the border: Free trade and George 'Hitler' Bush's program for Mexican genocide A critical issue facing the nation in this presidential election year is NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement. Bush and Clinton both back it. This proposed treaty with Mexico will mean slave-labor, the rampant spread of cholera, and throwing hundreds of thousands of workers onto the unemployment lines-on both sides of the border-all for the purpose of bailing out the Wall Street and City of London banks. In this 75-page Special Report, ElR's investigators tell the truth about what the banker-run politicians and media have tried to sell as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get economic growth started across the Americas. The Wall Street crowd-led by none other than Henry Kissinger-are going berserk to ram this policy through Congress. Kis singer threatened in April: "It should be signed by all parties, and should be defended on all sides as a political vision, and not merely as a trade agreement." Kissinger's pal David Rockefeller added: "Without the fast track, the course of history will be stopped." With this report, ElR's editors aim to stop Rockefeller and his course of history-straight toward a banking dictatorship. $75 per copy ,. ' Make check or money order payable to: �ITlli News Service P.o. Box 17390 Washington, D.C. 20041-0390 Mastercard and Visa accepted. Founder and Contributing Editor: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. Editor: Nora Hamerman From the Editor Managing Editors: John Sigerson, Susan Welsh Assistant Managing Editor: Ronald Kokinda Editorial Board: Warren Hamerman, Melvin Klenetsky, Antony Papert, Gerald Rose, Allen Salisbury, Edward Spannaus, Nancy Spannaus, We publish in this issue two speeches, which are especially rele Webster Tarpley, Carol White, Christopher White vant in light of the current monetary crisis. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS 29881 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS NATIONAL HISPANIC HERITAGE Troducing Hispanic Artists and Covering Top "This May Well Be the Case

September 19, 1977 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 29881 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS NATIONAL HISPANIC HERITAGE troducing Hispanic artists and covering top "This may well be the case. But what 1s WEEK IN CONNECTICUT ics of national interest. at stake for the nation is not the adequacy We trust that we can count on your sup of current profits by business standards-it port both at the Capitol and with your con is rather the rate of drllling and production. stituency here in Connecticut. As a re "Even if proposed pricing structures pro HON. WILLIAM R. COTTER vided for sufficient profit, is the price struc OF CONNECTICUT source, we know your office is invaluable to us; and 1! we can be o! any assistance to ture adequate to generate the level of cash IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES you, in terms o! disseminating information, fiow necessary to mount and sustain the drilling effort required to meet the planned Monday, September 19, 1977 please don't hesitate to contact our office. Sincerely, 1985 oil and gas production goals? We con Mr. COTTER. Mr. Speaker, September FRANK MARRERO, clude ... that it is not, and that 1985 na 11 through 17 was National Hispanic Executive Producer, Project Officer. tional oil and gas production will be as much as five million barrels a day below the NEP Heritage Week, an event that recognized goal." the important role of Hispanic-Ameri They said $699 blllion in 1976 prices must cans in our Nation's life. Connecticut, be invested to fulfill production and con where the Hispanic community numbers UNITED STATES-MORE OIL AND servation targets o! NEP. -

The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference, 2013 Event Videos Now on Youtube

This version of Total HTML Converter is unregistered. NewsFollowup Franklin Scandal Omaha Sitemap Obama Comment Search Pictorial index home Midwest 9/11 Truth Go to Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference 2014 page Architects & Engineers Conference, 2013 for 9/11 Truth Mini / Micro Nukes 9/11 Truth links Event videos now on YouTube, World911Truth Cheney, Planning and Decision Aid System speakers: Sonnenfeld Video of 9/11 Ground Zero Victims and Rescuers Wayne Madsen , Investigative Journalist, and 9/11 Whistleblowers AE911Truth James Fetzer, Ph.D., Founder of Scholars for 9/11 Truth Ed Asner Contact: Steve Francis Compare competing Kevin Barrett, co-founder Muslim Jewish Christian Alliance for 9/11 Truth [email protected] theories The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference 2014 is now in the planning stages. Top 9/11 Documentaries US/British/Saudi/Zionists Research Speakers: The Midwest 9/11 Wayne Madsen Truth Conference Jim Fetzer Wayne Madsen is a Washington, DC-based investigative James H. Fetzer, a former Marine Corps officer, is This version of Total HTML Converter is unregistered. journalist, author and columnist. He has written for The Village Distinguished McKnight Professor Emeritus on the Duluth Voice, The Progressive, Counterpunch, Online Journal, campus of the University of Minnesota. A magna cum CorpWatch, Multinational Monitor, News Insider, In These laude in philosophy graduate of Princeton University in Times, and The American Conservative. His columns have 1962, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant and appeared in The Miami Herald, Houston Chronicle, became an artillery officer who served in the Far East. Philadelphia Inquirer, Columbus Dispatch, Sacramento Bee, After a tour supervising recruit training in San Diego, he and Atlanta Journal-Constitution, among others. -

Joseph Hansen Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf78700585 No online items Register of the Joseph Hansen papers Finding aid prepared by Joseph Hansen Hoover Institution Archives 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305-6003 (650) 723-3563 [email protected] © 1998, 2006, 2012 Register of the Joseph Hansen 92035 1 papers Title: Joseph Hansen papers Date (inclusive): 1887-1980 Collection Number: 92035 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 109 manuscript boxes, 1 oversize box, 3 envelopes, 1 audio cassette(46.2 linear feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, notes, minutes, reports, internal bulletins, resolutions, theses, printed matter, sound recording, and photographs relating to Leon Trotsky, activities of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States, and activities of the Fourth International in Latin America, Western Europe and elsewhere. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Creator: Hansen, Joseph, Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Archives. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Joseph Hansen papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Archives in 1992. Accruals Materials may have been added to the collection since this finding aid was prepared. To determine if this has occurred, find the collection in Stanford University's online catalog at http://searchworks.stanford.edu . Materials have been added to the collection if the number of boxes listed in the online catalog is larger than the number of boxes listed in this finding aid. -

January 2011-56P

Gwangju News International Magazine for Gwangju and Jeollanam-do January 2011 Issue No. 107 Gwangju FC The Plight of the Moon Bears Kunsthalle Roundup 2011 GIC 1st Korean Language Class Weekday Classes Saturday Classes Level Days Textbook Level Textbook 서강한국어 1A 서강한국어 1A Beginner 1-1 Tuesday & Thursday Beginner 1-1 (Pre-lesson ~ Lesson 1) (Pre-lesson ~ Lesson 1) 서강한국어 1A 서강한국어 1A Beginner 1-2 Monday & Wednesday Beginner 1-2 (Lesson 2 ~ Lesson 6) (Lesson 2 ~ Lesson 6) 서강한국어 1B 서강한국어 1B Beginner 2-2 Tuesday & Thursday Beginner 2-1 (Lesson 5 ~ Lesson 8) (Lesson 1 ~ Lesson 4) 서강한국어 2B Intermediate 2-1 Tuesday & Thursday - Period: Jan.8 - Feb. 24, 2011 (Lesson 1 ~ Lesson 4) (Every Saturday for 7 weeks) - Class hours: 10:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. - Period: Jan. 10 - Feb. 19, 2011 (Twice a week for 7 weeks) (2 hours) - Class hours: 10:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. (2 hours) - Tuition fee: 50,000 won - Tuition fee : 80,000 won (GIC membership fee: 20,000 won/ (GIC membership fee: 20,000 won/ year year and textbooks excluded) cash only and textbooks excluded) cash only * The tuition fee is non-refundable after the first week. To register, please send your information: full name, Note * A class may be canceled if fewer than 5 people sign up. contact number, working place and preferable level * Textbooks can be purchased at the GIC to [email protected] GIC is located on the 5th floor of the Jeon-il building, the same building as the Korean Exchange Bank, downtown. -

Bob· Chester: Trotskyist Leader & Educator by Ed Harris American Workers Party, Led by A.J

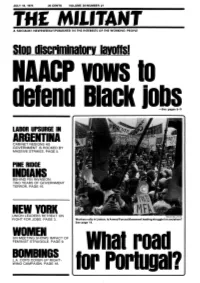

JULY 18, 1975 25 CENTS VOLUME 39/NUMBER 27 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE SIOD discriminatory IBVOIIS! LABOR UPSURGE IN ARGENTINA CABINET RESIGNS AS GOVERNMENT IS ROCKED BY MASSIVE STRIKES. PAGE 5. PINE RIDGE I IS BEHIND FBI INVASION: TWO YEARS OF GOVERNMENT TERROR .. PAGE 16. lEW YORK UNION LEADERS RETREAT ON Militant/Mary Scully FIGHT FOR JOBS. PAGE 3. Workers rally in Lisbon. Is Armed Forces Movement leading struggle for socialism? See page 14. WOMEN UN MEETING SHOWS IMPACT OF FEMINIST STRUGGLE. PAGE 9. liNGS. L.A. COPS COVER UP RIGHT WING CAMPAIGN. PAGE 18. 7II In Brief THIS UNCOMMON CAUSE: The Militant has been reporting front of Japan; and if Japan were directly exposed and WEEK'S how Common Cause chief John Gardner has been going to threatened," Helms said, "her intricate economy bat for the two-party system. The Washington Star recently interwoven so closely with the needs and stability ·of the MILITANT asked him if he didn't think that this was a strange cause Western economies-would collapse." for the so-called People's Lobby to embrace "when many 3 Union leaders retreat voters are expressing no confidence in either the Democratic GAY RIGHTS GAIN: The U.S. Civil Service Commission from jobs fight or Republican parties." The question referred to the has backed off from its policy of excluding homosexuals 4 AFSCME ends Pa. strike Common Cause-promoted public election financing law, f~om government jobs. Newly issued guidelines state that with few gains · which provides tax money to the Democrats and Republi court.decisions and injunctions require "the same standard cans, and excludes smaller parties. -

'War on Terror'. a Study of Attribution in Elite Newspaper Coverage

Sourcing and Framing the 'War on Terror'. A Study of Attribution in Elite Newspaper Coverage. Morgan Stack (B.Sc M.Acc MBS) Supervisor: Dr. Kevin Rafter School of Communications Dublin City University A thesis submitted to Dublin City University in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. PhD June 2013 DECLARATION I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy , is entirely my own work, that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ____________________ (Candidate) ID No.: 59110937 Date:_______________________ 2 ABSTRACT The 'war on terror', described as the most important framing case of our time, is analysed in this study of elite newspaper coverage primarily in terms of the 'attribution of responsibility' for specific terrorist attacks. This is justified by the role of attribution in terms of 'primary definition', the exertion of political power in the text, and the constitutive role of attribution in public opinion formation. In addition to an analysis of how the coverage 'framed' attribution, the study also attempts to speak to the validity or otherwise of the 'mythical metanarrative' interpretation of the 'war on terror'. The study proceeds to analyse the nature of news sources drawn upon in the coverage, most specifically again with respect to the construction of attribution. -

®Ije Liigtjtistmim Oktfrtff

®Ije liigtjtistmim Oktfrtff An Independent Newspaper Devoted to the Interests of the People of Hightstown and Vicinity 108TH YEAR—No. 10 HIGHTSTOWN GAZETTE, MERCER COUNTY, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, AUGUST 30, 1956 PRICE—FIVE CENTS Forecast 11 Honesty Is Wonderful! Heavy Fines, HHS Class Assignments, Bus Passengers Listed 1529 Area Students to Answer Deaths During Classroom assignments for the Brings Joy to Youngster Jail Sentences high school students, grades 9 through 12 and bus passenger School Bells Next Wednesday; Dear Editor: purse. Forget the mailing charges lists for the 1956-57 term are re Holiday Period leased by Melvin H. Kreps, su In these days when we read so as they are on me, but never forget To Disorderlies many news articles featuring crime perintendent of schools. They the impression of honesty you will may be found on pages 3 and 7 More than 400 Persons of varying degrees, we thought the 21 New Teachers Join Staff following might be as heartwarm have no doubt learned by having it Man Assessed $205, of this week’s issue of The Ga zette. Expected to Suffer ing to others as it is to ourjamily. returned to you. If this stays with While on our vacation this sum you through life, I will more than Loses License 2 Yrs. 8 Per Cent Increase in Enrollment Over Last Year; Some Kind of Injury mer our seven-year-old son, Eric, be repaid for any effort I put forth On Motor Vehicle Count lost his wallet containing all of his so that your property would be re Jews to Usher Faculty Members to Report 10:30 a.m.