'War on Terror'. a Study of Attribution in Elite Newspaper Coverage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Terrorism on Discriminatory Attitudes and Behaviors

Shades of Intolerance: The Influence of Terrorism on Discriminatory Attitudes and Behaviors in the United Kingdom and Canada. by Chuck Baker A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs Written under the direction of Dr. Gregg Van Ryzin and approved by ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Newark, New Jersey May, 2015 Copyright page: © 2015 Chuck Baker All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Influence of Terrorism on Discriminatory Attitudes and Behaviors in the United Kingdom and Canada by Chuck Baker Dissertation Director: Dr. Gregg Van Ryzin, Ph.D. Terrorism has been shown to have a destabilizing impact upon the citizens of the nation- state in which it occurs, causing social distress, fear, and the desire for retribution (Cesari, 2010; Chebel d’Appollonia, 2012). Much of the recent work on 21st century terrorism carried out in the global north has placed the focus on terrorism being perpetuated by Middle East Muslims. In addition, recent migration trends show that the global north is becoming much more diverse as the highly populated global south migrates upward. Population growth in the global north is primarily due to increases in the minority presence, and these post-1960 changes have increased the diversity of historically more homogeneous nations like the United Kingdom and Canada. This research examines the influence of terrorism on discriminatory attitudes and behaviors, with a focus on the United Kingdom in the aftermath of the July 7, 2005 terrorist attacks in London. -

The “Anti-Nationals” RIGHTS Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India WATCH

India HUMAN The “Anti-Nationals” RIGHTS Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India WATCH The “Anti-Nationals” Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-735-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org February 2011 ISBN 1-56432-735-3 The “Anti-Nationals” Arbitrary Detention and Torture of Terrorism Suspects in India Map of India ............................................................................................................. 1 Summary ................................................................................................................. 2 Recommendations for Immediate Action by the Indian Government .................. 10 Methodology ......................................................................................................... 12 I. Recent Attacks Attributed to Islamist and Hindu Militant Groups ....................... -

Immigration Policy, Race Relations and Multiculturalism in Post-Colonial Great Britain Flora Macivor Épouse Lamoureux

The Setting Sun : Immigration Policy, Race Relations and Multiculturalism in Post-Colonial Great Britain Flora Macivor Épouse Lamoureux To cite this version: Flora Macivor Épouse Lamoureux. The Setting Sun : Immigration Policy, Race Relations and Multi- culturalism in Post-Colonial Great Britain. History. 2010. dumas-00534579 HAL Id: dumas-00534579 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-00534579 Submitted on 10 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DU SUD TOULON-VAR FACULTE DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES MASTER RECHERCHE : CIVILISATIONS CONTEMPORAINES ET COMPAREES ANNÉE 2009-2010, 1ERE SESSION THE SETTING SUN: IMMIGRATION POLICY, RACE RELATIONS AND MULTICULTURALISM IN POST- COLONIAL GREAT BRITAIN FLORA MACIVOR LAMOUREUX UNDER THE DIRECTION OF PROFESSOR GILLES LEYDIER ii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 THE FIRST BRITISH ASIANS: A HISTORY .............................................................. 8 I. The Colonial -

The Old Mole and New Mole Files!)

1 “LENINST BOOMERS” BUILD “THE FIFTH INTERNATIONAL”: THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE LABOR COMMITTEE (PLUS THE OLD MOLE AND NEW MOLE FILES!) Introduction: This series of FactNet posts provides the most detailed look at the early history of the NCLC from LaRouche‟s leaving the SWP in late 1965 to the major faction fight inside the organization in 1971. The files focus most on the early NCLC in two key cities, New York and Philadelphia. However there is some mention of the NCLC group in Baltimore as well as a detailed picture of the early European organization. As part of the research, LaRouche Planet includes two detailed series of posts by Hylozoic Hedgehog (dubbed “the Old Mole Files” and “the New Mole Files”) based on archival research. Much of the discussion involves the proto-LaRouche grouping and its role in SDS, the Columbia Strike, and the New York Teachers Strike in New York as well as the group‟s activity in Philadelphia. Finally, this series of posts can also be read as a continuation of the story of LaRouche and the NCLC begun by the “New Study” also posted on LaRouche Planet which covers LaRouche‟s history from his early years in New Hampshire and Massachusetts to his relocating to New York City in the early 1950s and his activity inside the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party (SWP) until he left the SWP in late 1965. WAYBACK to 1966: How it all began The Free University and CIPA: Origins of the SDS Labor Committees. (More notes from the archives) ―For two years, beginning during the Summer of 1966; the Marcus class at a ramshackle New York Free School premises on New York City's 14th Street was the motor for the growth of a tiny group, the hard core of the future Labor Committees.‖ -- From: The Conceptual History of the Labor Committees by L. -

Breathing Life Into the Constitution

Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering In India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Alternative Law Forum Bengaluru Breathing Life into the Constitution Human Rights Lawyering in India Arvind Narrain | Saumya Uma Edition: January 2017 Published by: Alternative Law Forum 122/4 Infantry Road, Bengaluru - 560001. Karnataka, India. Design by: Vinay C About the Authors: Arvind Narrain is a founding member of the Alternative Law Forum in Bangalore, a collective of lawyers who work on a critical practise of law. He has worked on human rights issues including mass crimes, communal conflict, LGBT rights and human rights history. Saumya Uma has 22 years’ experience as a lawyer, law researcher, writer, campaigner, trainer and activist on gender, law and human rights. Cover page images copied from multiple news articles. All copyrights acknowledged. Any part of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted as necessary. The authors only assert the right to be identified wtih the reproduced version. “I am not a religious person but the only sin I believe in is the sin of cynicism.” Parvez Imroz, Jammu and Kashmir Civil Society Coalition (JKCSS), on being told that nothing would change with respect to the human rights situation in Kashmir Dedication This book is dedicated to remembering the courageous work of human rights lawyers, Jalil Andrabi (1954-1996), Shahid Azmi (1977-2010), K. Balagopal (1952-2009), K.G. Kannabiran (1929-2010), Gobinda Mukhoty (1927-1995), T. Purushotham – (killed in 2000), Japa Lakshma Reddy (killed in 1992), P.A. -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 19, Number 38, September

fast track to rule by the big banks EIR Special Report, May 1991 Auschwitz below the border: Free trade and George 'Hitler' Bush's program for Mexican genocide A critical issue facing the nation in this presidential election year is NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement. Bush and Clinton both back it. This proposed treaty with Mexico will mean slave-labor, the rampant spread of cholera, and throwing hundreds of thousands of workers onto the unemployment lines-on both sides of the border-all for the purpose of bailing out the Wall Street and City of London banks. In this 75-page Special Report, ElR's investigators tell the truth about what the banker-run politicians and media have tried to sell as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get economic growth started across the Americas. The Wall Street crowd-led by none other than Henry Kissinger-are going berserk to ram this policy through Congress. Kis singer threatened in April: "It should be signed by all parties, and should be defended on all sides as a political vision, and not merely as a trade agreement." Kissinger's pal David Rockefeller added: "Without the fast track, the course of history will be stopped." With this report, ElR's editors aim to stop Rockefeller and his course of history-straight toward a banking dictatorship. $75 per copy ,. ' Make check or money order payable to: �ITlli News Service P.o. Box 17390 Washington, D.C. 20041-0390 Mastercard and Visa accepted. Founder and Contributing Editor: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. Editor: Nora Hamerman From the Editor Managing Editors: John Sigerson, Susan Welsh Assistant Managing Editor: Ronald Kokinda Editorial Board: Warren Hamerman, Melvin Klenetsky, Antony Papert, Gerald Rose, Allen Salisbury, Edward Spannaus, Nancy Spannaus, We publish in this issue two speeches, which are especially rele Webster Tarpley, Carol White, Christopher White vant in light of the current monetary crisis. -

The Representation of Extremists in Western Media

2015 The Representation of Extremists in Western Media As radicalised Muslim converts gain ever greater attention within the War on Terror (WoT) and the media, an investigation into their portrayal and the associated discourses becomes ever more relevant. This study aims to shed more light on the representation of these extremist individuals in the Western media, specifically white converts to Islam who become radicalised. It explores whether there is indeed a difference between the portrayal of female and male extremists within this context and seeks to reveal any related social or national anxieties. This research paper has a qualitative research design, comprising the comparative case study model and discourse analysis. The main sources for the discourse analysis are English-speaking Western newspapers. Laura Kapelari Supervisor: Jacqueline De Matos Ala A research report submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations University of the Witwatersrand 2015 Declaration I declare that this research report is my own unaided work except where I have explicitly indicated otherwise. This research report is submitted towards the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations by coursework and research report at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at any other university. _____________________________ Laura Kapelari 1 Table of Contents Declaration ................................................................................................................................... -

The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference, 2013 Event Videos Now on Youtube

This version of Total HTML Converter is unregistered. NewsFollowup Franklin Scandal Omaha Sitemap Obama Comment Search Pictorial index home Midwest 9/11 Truth Go to Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference 2014 page Architects & Engineers Conference, 2013 for 9/11 Truth Mini / Micro Nukes 9/11 Truth links Event videos now on YouTube, World911Truth Cheney, Planning and Decision Aid System speakers: Sonnenfeld Video of 9/11 Ground Zero Victims and Rescuers Wayne Madsen , Investigative Journalist, and 9/11 Whistleblowers AE911Truth James Fetzer, Ph.D., Founder of Scholars for 9/11 Truth Ed Asner Contact: Steve Francis Compare competing Kevin Barrett, co-founder Muslim Jewish Christian Alliance for 9/11 Truth [email protected] theories The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference 2014 is now in the planning stages. Top 9/11 Documentaries US/British/Saudi/Zionists Research Speakers: The Midwest 9/11 Wayne Madsen Truth Conference Jim Fetzer Wayne Madsen is a Washington, DC-based investigative James H. Fetzer, a former Marine Corps officer, is This version of Total HTML Converter is unregistered. journalist, author and columnist. He has written for The Village Distinguished McKnight Professor Emeritus on the Duluth Voice, The Progressive, Counterpunch, Online Journal, campus of the University of Minnesota. A magna cum CorpWatch, Multinational Monitor, News Insider, In These laude in philosophy graduate of Princeton University in Times, and The American Conservative. His columns have 1962, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant and appeared in The Miami Herald, Houston Chronicle, became an artillery officer who served in the Far East. Philadelphia Inquirer, Columbus Dispatch, Sacramento Bee, After a tour supervising recruit training in San Diego, he and Atlanta Journal-Constitution, among others. -

Lawyers' Musings

The Student Lawyers' Musings May '20 An ICFAI Law School Publication Contents Foreword Our Contributors 1.College in times of COVID........................................................................................1 2.Marital Rape.....................................................................................................................2 3. Event Details - National Seminar on International Trade Law........3 4. The Impact of Online Marketing on Small and Medium Scale Enterprises.......................................................................................................................4 5. Event Details - ICON 2020.....................................................................................6 6. Future of Human Rights and Education in the Global Scenario..9 7. Event Details - Open Mic......................................................................................13 8. Human Rights violations at Workplace.......................................................14 9. Event Details - National Seminar on Competition Law....................16 10. Internet Freedom - A Fundamental Right.................................................18 11. KUछ...................................................................................................................................20 12. Achievers' - Mooters and Shooters.................................................................21 13. Interview.........................................................................................................................22 -

January 2011-56P

Gwangju News International Magazine for Gwangju and Jeollanam-do January 2011 Issue No. 107 Gwangju FC The Plight of the Moon Bears Kunsthalle Roundup 2011 GIC 1st Korean Language Class Weekday Classes Saturday Classes Level Days Textbook Level Textbook 서강한국어 1A 서강한국어 1A Beginner 1-1 Tuesday & Thursday Beginner 1-1 (Pre-lesson ~ Lesson 1) (Pre-lesson ~ Lesson 1) 서강한국어 1A 서강한국어 1A Beginner 1-2 Monday & Wednesday Beginner 1-2 (Lesson 2 ~ Lesson 6) (Lesson 2 ~ Lesson 6) 서강한국어 1B 서강한국어 1B Beginner 2-2 Tuesday & Thursday Beginner 2-1 (Lesson 5 ~ Lesson 8) (Lesson 1 ~ Lesson 4) 서강한국어 2B Intermediate 2-1 Tuesday & Thursday - Period: Jan.8 - Feb. 24, 2011 (Lesson 1 ~ Lesson 4) (Every Saturday for 7 weeks) - Class hours: 10:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. - Period: Jan. 10 - Feb. 19, 2011 (Twice a week for 7 weeks) (2 hours) - Class hours: 10:30 a.m. – 12:30 p.m. (2 hours) - Tuition fee: 50,000 won - Tuition fee : 80,000 won (GIC membership fee: 20,000 won/ (GIC membership fee: 20,000 won/ year year and textbooks excluded) cash only and textbooks excluded) cash only * The tuition fee is non-refundable after the first week. To register, please send your information: full name, Note * A class may be canceled if fewer than 5 people sign up. contact number, working place and preferable level * Textbooks can be purchased at the GIC to [email protected] GIC is located on the 5th floor of the Jeon-il building, the same building as the Korean Exchange Bank, downtown. -

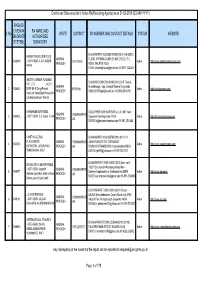

District and State Wise List of Active RA(Recruiting Agents) As on 21-02-2018 (DD-MM-YYYY)

District and State wise list of Active RA(Recruiting Agents) as on 21-02-2018 (DD-MM-YYYY) RAID(AS GIVEN IN RA NAME AND S. No. STATE DISTRICT RC NUMBER AND CONTACT DETAILS STATUS WEBSITE EMIGRATE AUTHORISED SYSTEM) SIGNATORY B-0410/AP/PER/1000/5/8419/2009;DNO 19-8-85/F5, I AKBAR TRAVEL SERVICES ANDHRA FLOOR, KRISHNA COMPLEX AIR CIRCLE, R C 1 RA8419 ; AUTH-SIGN: A D M AKBAR CHITTOOR Active http://www.akbartravelservices.com PRADESH ROAD TIRUPATI INDIA KHAN 517501;[email protected];91-0877-2243407 WESTIN CAREER PLANNER B-0485/AP/COM/1000+/5/8960/2013;GVR Towers, PVT. LTD. ; AUTH- ANDHRA Bharathinagar, Opp. Vinayak Theatre Vijayawada 2 RA8960 SIGN: Mr K DurgaPrasad KRISHNA Active http://westincareer.com/ PRADESH INDIA 520008;[email protected];91-866-2546765 Naidu,Mr KodaliGopi Prasad,Mrs UmaMurleedharan Warrier KANNAN ENTERPRISES 0252/AP/PER/1000+/5/4975/97;D.no:5-160/1 New ANDHRA VISHAKHAPATN 3 RA4975 ; AUTH-SIGN: S G Vijaya Kumar Gajuwaka Visakhapatnam INDIA Active http://kannanenterprises.com PRADESH AM 530026;[email protected];91-891-2511484 VANITHA GLOBAL B-0458/AP/PER/1000+/5/5745/2001;48-13-1/1 PLACEMENTS ; ANDHRA VISHAKHAPATN JANAKIRAMA STREET,SRINAGAR, 4 RA5745 Active http://www.vgplacements.com AUTH-SIGN: JARARDHAN PRADESH AM VISAKHAPATNAM,530016 Visakhapatnam INDIA THIMMANANA RAO 530016;[email protected];91-891-2573112 B-0556/AP/PART/1000+/5/8977/2013;Door -no:6- SAI JAYANTHI ENTERPRISES 168,S1,Sai Jayanthi Residency Naidu New ; AUTH-SIGN: Jayanthi ANDHRA VISHAKHAPATN 5 RA8977 Quarters,Gopalapatnam Visakhapatnam -

Stepford Four” Operation: How the 2005 London Bombings Turned E

The 7/7 London Bombings and MI5’s “Stepford Four” Operation: How the 2005 London Bombings Turned every Muslim into a “Terror Suspect” By Karin Brothers Global Research, May 26, 2017 Global Research This article first published on July 12, 2014 provides a historical understanding of the wave of Islamophobia sweeping across the United Kingdom since 7/7. This article is of particular relevance in understanding the May 2017 Manchester bombing and its tragic aftermath. (M. Ch. GR Editor) Nine Years Ago, the 7/7 London Bombing This article is dedicated to former South Yorkshire terror analyst Tony Farrell who lost his job but kept his integrity, and with thanks to the documentation provided by the July 7th Truth Campaign “:One intriguing aspect of the London Bombing report is the fact that the MI5 codename for the event is “Stepford”. The four “bombers” are referred to as the “Stepford four”. Why is this the case? … the MI5 codename is very revealing in that it suggests the operation was a carefully coordinated and controlled one with four compliant and malleable patsies following direct orders. Now if MI5 has no idea who was behind the operation or whether there were any orders coming from a mastermind, why would they give the event the codename “Stepford”? ” (Steve Watson, January 30, 2006 Prison Planet) Background The word was out that there was easy money to be made by Muslims taking part in an emergency- preparedness operation. Mohammad Sidique Khan — better known by his western nickname “Sid” — had been approached by his contact, probably Haroon Rashid Aswat who was in town, about a big emergency preparedness operation that was looking for local Pakistanis who might take the part of pretend “suicide bombers” for the enactment.