American Trotskyism and the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stalinism and Trotskyism in Vietnam

r Telegram: Defend the DRV-NLF! The following telegram was sent as the u.s. imperialists mined Haiphong harbor and the North Vietnamese coast. At the time Soviet bureaucrats were preparing to receive Nixon in Moscow just as their Chinese counterparts a few months earlier wined and dined him in Peking as he terror-bombed Vietnam. Embassy of the U.S.S.R. Washington, D.C. U.N. Mission of the People's Republic of China New York, N.Y. On behalf of the urgent revolutionary needs of the international working class and in accord with the inevitable aims of our future worker~ government in the United States, we demand that you immediately expand shipment of military supplies of the highest technical quality to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and that you offer the DRV the fullest all sided assistance including necessary Russian-Chinese joint military collaboration. No other course will serve at this moment of savage imperialist escalation against the DRV and the Indochinese working people whose military victories have totally shattered the myths of the Vietnamization and pacification programs of Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon. signed: Political Bureau, Spartacist League of the U.S. 8 May 1972 copies to: D RV and N LF delegations, Paris -from Workers Vanguard No.9, June 1972 6 n p Stalinism and Trotskyism In• Vietnam ~···· l,~ ~ r SPARTACIST PUBLISHING co. Box 1377, G.P.O. New York, N.Y. 10001, U.S.A . • December 1976 Ho Chi Minh Ta Thu Thau CONTENTS CHAPTER I In Defense of Vietnamese Trotskyism (I:·: • >'~ Stalinism and Trotskyism in Vietnam ................... -

Dobbs on Truckers Strike Rebecca Finch, New York Socialist Workers Party Candi in New York City

FEBRUARY 22, 1974 25 CENTS VOLUME 38,1NUMBER 7 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE On-the-scene rel}orts Minnesota truckers vote Feb. 10 to continue strike. Reporters for the Militant aHended strike meetings around the country. For their reports, and special feature on Teamsters union and independent truckers in 1930s and today, see pages 5-9. riti m1ners• ae eat In Brief BERRIGAN REFUSED JOB AT ITHACA: 300 angry prisoners labeled "special offenders." students confronted Ithaca College President Henry Phillips Delegations from Rhode Island, Maine, and Connecti Feb. 7, demanding to know why the college withdrew an cut attended the rally, which was very spirited, despite offer of a visiting professorship to Father Daniel Berrigan. a heavy snowstorm. Speakers at the rally included Richard THIS The college made the offer last December and President Shapiro, executive director of the Prisoners Rights Project; Phillips withdrew it one month later without consulting Russell Carmichael of the New England Prisoners Associa students and faculty. tion; State Representative William Owens; and Jeanne Laf WEEK'S This was the second meeting called by students since ferty, Socialist Workers Party candidate for attorney gen a petition signed by 1,000 students failed to elicit a eral of Massachusetts. MILITANT response from the administration. The students are pro testing the arbitrary decision and demanding a full ex PUERTO RICAN POETRY FESTIVAL PLANNED: The 3 Union organizers speak planation for the withdrawal of the offer. Berrigan recently Committee for Puerto Rican Decolonization, an organiza out on fight of women criticized Israel's expansionist policies in the Mideast, which tion supporting the independence of Puerto Rico, is spon workers brought slanderous charges from pro-Zionist groups that soring a festival of Puerto Rican poetry. -

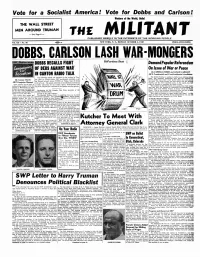

Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite!

Vote for a Socialist America! Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite! THE WALL STREET MEN AROUND TRUMAN — See Page 4 — THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 4, 1948 Vol. X II -.No. 40 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS, CARLSON LASH WAR <yMONGERS ;$WP flection New* DOBBS RECALLS FI6HT Bp-Partisan Duet flj Demand Popular Referendum OF DEBS AGAINST WAR On Issue o f W ar or Peace By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON IN CANTON RADIO TALK SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates The following speech was broadcast to the workers of Can The United Nations is meeting in Paris in an ominous atmos- phere. The American imperialists have had the audacity to ton, Ohio, by Farrell Dobbs, SWP presidential candidate, over By George Clarke launch another war scare a bare month before the voters go to the Mutual network station WHKK on Friday, Sept. 24 from the polls. The Berlin dispute has been thrown into the Security SWP Campaign Manager 4 :45 to 5 p.m. The speech, delivered on the thirtieth anniversary Council; and the entire capitalist press, at this signal, has cast Grace Carlson got the kind of of Debs’ conviction for his Canton speech, demonstrates how aside all restraint in pounding the drums of war. welcome-home reception when she the SWP continues the traditions of the famous socialist agitator. The insolence of the Wan Street rulers stems from their assur arrived in Minneapolis on Sept. ance that they w ill continue to monopolize the government fo r 21 that was proper and deserving another four years whether Truman or Dewey sits in the White fo r the only woman candidate fo r Introduction by Ted Selander, Ohio State Secretary of the House. -

Efforts to Establish a Labor Party I!7 America

Efforts to establish a labor party in America Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors O'Brien, Dorothy Margaret, 1917- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 15:33:37 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553636 EFFORTS TO ESTABLISH A LABOR PARTY I!7 AMERICA by Dorothy SU 0s Brlen A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Economics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate College University of Arizona 1943 Approved 3T-:- ' t .A\% . :.y- wissife mk- j" •:-i .»,- , g r ■ •: : # ■ s &???/ S 9^ 3 PREFACE The labor movement In America has followed two courses, one, economic unionism, the other, political activity* Union ism preceded labor parties by a few years, but developed dif ferently from political parties* Unionism became crystallized in the American Federation of Labor, the Railway Brotherhoods and the Congress of Industrial Organization* The membership of these unions has fluctuated with the changes in economic conditions, but in the long run they have grown and increased their strength* Political parties have only arisen when there was drastic need for a change* Labor would rally around lead ers, regardless of their party aflliations, -

Albert Glotzer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n989d No online items Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Processed by Dale Reed. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Register of the Albert Glotzer 91006 1 papers Register of the Albert Glotzer papers Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Dale Reed Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from Microsoft Word and MARC record by Supriya Wronkiewicz. © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Albert Glotzer papers Dates: 1919-1994 Collection Number: 91006 Creator: Glotzer, Albert, 1908-1999 Collection Size: 67 manuscript boxes, 6 envelopes (27.7 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Correspondence, writings, minutes, internal bulletins and other internal party documents, legal documents, and printed matter, relating to Leon Trotsky, the development of American Trotskyism from 1928 until the split in the Socialist Workers Party in 1940, the development of the Workers Party and its successor, the Independent Socialist League, from that time until its merger with the Socialist Party in 1958, Trotskyism abroad, the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937, legal efforts of the Independent Socialist League to secure its removal from the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations, and the political development of the Socialist Party and its successor, Social Democrats, U.S.A., after 1958. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English Access Collection is open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. 17-1200 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- INDEPENDENT PARTY, ET AL., Petitioners, v. ALEX PADILLA, CALIFORNIA SECRETARY OF STATE, Respondent. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Petition For Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BRIEF OF CITIZENS IN CHARGE AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- --------------------------------- PAUL A. ROSSI Counsel of Record 316 Hill Street Mountville, PA 17554 (717) 961-8978 [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae ================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the party names INDEPENDENT PARTY and AMERICAN INDEPENDENT PARTY are so sim- ilar to each other that voters will be misled if both of them appeared on the same California ballot. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTION PRESENTED................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................... ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................. ii STATEMENT OF INTEREST ............................. 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................................... 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................ 3 CONCLUSION .................................................... -

Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism Erik Meddles Regis University

Regis University ePublications at Regis University All Regis University Theses Spring 2010 Partisan of Greatness: Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism Erik Meddles Regis University Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Meddles, Erik, "Partisan of Greatness: Andre Malraux's Devotion to Caesarism" (2010). All Regis University Theses. 544. https://epublications.regis.edu/theses/544 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Regis University Theses by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regis University Regis College Honors Theses Disclaimer Use of the materials available in the Regis University Thesis Collection (“Collection”) is limited and restricted to those users who agree to comply with the following terms of use. Regis University reserves the right to deny access to the Collection to any person who violates these terms of use or who seeks to or does alter, avoid or supersede the functional conditions, restrictions and limitations of the Collection. The site may be used only for lawful purposes. The user is solely responsible for knowing and adhering to any and all applicable laws, rules, and regulations relating or pertaining to use of the Collection. All content in this Collection is owned by and subject to the exclusive control of Regis University and the authors of the materials. It is available only for research purposes and may not be used in violation of copyright laws or for unlawful purposes. -

Sam Gordon Bio-Bibliographical Sketch

Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet Sam Gordon Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: • Basic biographical data • Biographical sketch • Selective bibliography • Notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: Sam Gordon Other names (by-names, pseud., etc.): Burton ; Drake ; Harry ; Joe ; Joad ; J.S. ; Paul G. Stevens ; J. Stuart ; J.B. Stuart ; J.E.B. Stuart ; Ted ; Tom Date and place of birth: May 5, 1910, ??? (Austria-Hungary) Date and place of death: March 12, 1982, London (Britain) Nationality: USA Occupations, careers, etc.: Printer, journalist, translator, seaman, organizer Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1929 - 1982 (lifelong Trotskyist) Biographical sketch Sam Gordon was an outstanding Trotskyist who during the 1940s played an eminent rôle as a liaison man between the American SWP and the European Trotskyists as well as within the leading bodies of the Fourth In ternational. The following biographical sketch is chiefly based on the material listed in the last paragraph of the Selective bibliography section below. Sam Gordon1 was born on May 5, 1910 as a son of Yiddish speaking Jewish parents living in that part of Poland which then belonged to the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. However, when Sam was still a baby, the family moved to Vienna, the Austrian capital, thus the boy grew up in a German speaking en vironment. In 1920, the family went to New York (USA) where Sam Gordon rapidly learnt English and got naturalized under the Americanized name of Gordon; as an adolescent he was fluent in three languages. In the early 1940s, Gordon got acquainted with Mildred Fellerman (b. 1923), a British teacher and Labour Party activist; when the two met again in Paris in 1947, they fell in love, and in 1948 they got married in the United States; in the 1950s they got a son. -

Active Political Parties in Village Elections

YEAR ACTIVE POLITICAL PARTIES IN VILLAGE ELECTIONS 1894 1895 1896 1897 Workingman’s Party People’s Party 1898 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1899 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1900 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1901 Workingman’s Party Citizen’s Party 1902 Citizen’s Party Reform Party Independent Party 1903 Citizen’s Party Independent Party 1904 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1905 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1906 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1907 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1908 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1909 Citizen’s Party Union Party 1910 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1911 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1912 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1913 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1914 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1915 Citizen’s Party People’s Party 1916 Citizen’s Party Independent Party American Party 1917 Citizen’s Party American Party 1918 Citizen’s Party American Party 1919 Citizen’s Party American Party 1920 Citizen’s Party American Party 1921 Citizen’s Party American Party 1922 Citizen’s Party American Party 1923 Citizen’s Party American Party 1924 Citizen’s Party American Party Independent Party 1925 Citizen’s Party American party 1926 Citizen’s party American Party 1927 Citizen’s Party No Opposition 1928 Citizen’s Party American Party 1929 Citizen’s Party American Party 1930 Citizen’s Party American Party 1931 Citizen’s Party American Party 1932 Citizen’s Party American Party 1933 Citizen’s Party American Party 1934 Citizen’s Party American Party 1935 Citizen’s Party American Party 1936 Citizen’s Party Old Citizen’s -

Call for a Workers and Farmers Government As Only Answer to Wall Street War-Makers Jft

Workers of the World, Unite! SPECIAL SWP CONVENTION ISSUE THE MILITANT __________ PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE __________________ Vol. XII— No. 28 267 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, JULY 12, 1948 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS AND CARLSON ADDRESS NATION IN BROADCASTS FROM SWP CONVENTION Call for a Workers and Farmers Government As Only Answer to Wall Street War-Makers Jft. SWP Candidates Address the Nation Inspiring Five-Day Gathering The Two Opens Presidential Campaign A m e rica s Of Socialist Workers Party By Art Preis James P. Cannon’s Key-Note Speech . NEW YORK, July 6 — Cheering to the echo the choice of Farrell Dobbs and Grace Carlson as first Over the ABC Network on July 1st Trotskyist candidates for U. S. President and Vice* President, the 13th National Convention of the So The following is the keynote speech delivered by James cialist Workers Party sum-® Cannon, National Secretary of the Socialist Workers Party, a propaganda blow been struck to the party’s 13th convention at 11:15 P. M. on July 1, and moiled the American peo in this country for the socialist broadcast over Radio network ABC at that time. ple to join with the SWP cause. That millions of people in a forward march to a Workers heard the SWP call is shown by Comrade Chairman, Delegates and Friends: and Farmers Government and the flood of letters and postcards We meet in National Convention at a t'ime of the gravest socialism. that hit the SWP National Head quarters in the first post-holiday world crisis— a crisis which contains the direct threat of a third Ih' an atmosphere charged with mail deliveries this morning. -

The Formation of the Communist Party, 1912–21

chapter 1 The Formation of the Communist Party, 1912–21 The Bolsheviks envisioned the October Revolution as the first in a series of pro- letarian revolutions. The Communist or Third International was to be a new, revolutionary international born from the wreckage of the social-democratic Second International. They sought to forge this international with what they saw as the best elements of the international working-class movement, those that had not betrayed socialism by supporting the war. The Comintern was to be a complete and definite break with the social-democratic politics of the Second International. In the face of the support of World War I by many labour and social-democratic leaders, significant sections of the workers’ movement rallied to the Bolsheviks.1 This was most pronounced in Italy and France, but in the United States as well the first Bolshevik supporters came from the left wing of the labour movement. In much of Europe, the social-democratic leaders either openly supported the militarism and imperialism of their ‘own’ ruling classes (such as when the German Social Democratic representatives voted for war credits on 4 August 1914) or (in the case of Karl Kautsky) provided ‘left’ cover to open social-chauvinists. In the United States, which entered the war late in the day, the party leadership as a whole opposed the war. However, the American socialist movement was still infected with electoral reformism, and a signifi- cant number of influential Socialists downplayed the party’s official opposi- tion to the war. This chapter examines how the American Communist movement devel- oped out of these antecedents. -

For All the People

Praise for For All the People John Curl has been around the block when it comes to knowing work- ers’ cooperatives. He has been a worker owner. He has argued theory and practice, inside the firms where his labor counts for something more than token control and within the determined, but still small uni- verse where labor rents capital, using it as it sees fit and profitable. So his book, For All the People: The Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America, reached expectant hands, and an open mind when it arrived in Asheville, NC. Am I disappointed? No, not in the least. Curl blends the three strands of his historical narrative with aplomb, he has, after all, been researching, writing, revising, and editing the text for a spell. Further, I am certain he has been responding to editors and publishers asking this or that. He may have tired, but he did not give up, much inspired, I am certain, by the determination of the women and men he brings to life. Each of his subtitles could have been a book, and has been written about by authors with as many points of ideological view as their titles. Curl sticks pretty close to the narrative line written by worker own- ers, no matter if they came to work every day with a socialist, laborist, anti-Marxist grudge or not. Often in the past, as with today’s worker owners, their firm fails, a dream to manage capital kaput. Yet today, as yesterday, the democratic ideals of hundreds of worker owners support vibrantly profitable businesses.