Journal of Mormon History Vol. 36, No. 4, Fall 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reform of Baptism and Confirmation in American Lutheranism

LOGIA 1 Review Essay: The Reform of Baptism and Confirmation in American Lutheranism Armand J. Boehme The Reform of Baptism and Confirmation in American Lutheranism. By Jeffrey A. Truscott. Drew University Studies in Liturgy 11. Lanham, Maryland & Oxford: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2003. his book1 is a study of the production of the baptismal the church.” Thus the crafters of LBW greatly expanded T and confirmation rites contained in Lutheran Book of the “assembly’s participation in the baptismal act” (pp. Worship (LBW).2 The theology that underlies LBW 33, 205). These changes flow from a theology of action and its understanding of worship has significantly (liturgy as the work of the people), which emphasizes altered the Lutheran understanding of baptism and the fact that the church or the congregation is the confirmation. The theological foundation of LBW has mediating agent of God’s saving activity (p. 33).6 For influenced other Lutheran church bodies, contributing LBW the sacraments are understood significantly to profound changes in the Lutheran ecclesiologically—as actions of the congregation (pp. landscape. As Truscott wrote, those crafting the 205-206)—rather than soteriologically—as God acting baptismal liturgy in LBW would have to “overturn” old to give his people grace and forgiveness. This leads to an theologies of baptism, deal with “a theology that” emphasis on baby drama, water drama, and other believed in “the necessity of baptism for salvation,” and congregational acts (pp. 24–26, 220). This theology of “would have to convince Lutherans of the need for a new action is tied to an analytic view of justification, that is, liturgical and theological approach to baptism” (p. -

Family History Library Class Calendar

Family History Library 35 North West Temple February 2020 Salt Lake City, UT 84150 Family History Library Class Calendar DATE / TIME CLASS SKILL LEVEL ROOM Germans from Russia: Finding Records for Volga Germans Tue, Feb 18, 11:30 AM Intermediate Main Lab (Webinar) Mon, Feb 24, 9:00 AM Immigration and Canadian Border Crossings Beginner Main B&C Tips and Tricks for Using FamilySearch Historical Records Mon, Feb 24, 10:00 AM Beginner Main B&C Collection Mon, Feb 24, 11:00 AM What History Didn't Teach You About the Mayflower Beginner Main B Mon, Feb 24, 1:00 PM What History Didn't Teach You About the Mayflower Beginner Main B Mon, Feb 24, 7:00 PM 10 Steps to Reclaiming Your African Roots (Webinar) Beginner Main Lab Tue, Feb 25, 11:00 AM What History Didn't Teach You About the Mayflower Beginner Main B Tue, Feb 25, 1:00 PM What History Didn't Teach You About the Mayflower Beginner Main B Chinese Genealogy Collections and Resources in Wed, Feb 26, 9:30 AM Beginner Main B&C FamilySearch The Family History Library: The Premier Destination for Wed, Feb 26, 12:15 PM Beginner Main B&C Genealogists Thu, Feb 27, 9:30 AM Using Archion to Find Protestant German Ancestors Beginner Main B&C Thu, Feb 27, 12:15 PM Mama Mia! Italian Research Basics Beginner Main B&C Thu, Feb 27, 4:30 PM Time Saving Strategies for Nordic Research Beginner Main A Thu, Feb 27, 6:35 PM RootsTech Beginner Night: DNA Beginner Main A Thu, Feb 27, 7:05 PM RootsTech Beginner Night: Introduction to Records Beginner Main A Thu, Feb 27, 7:45 PM RootsTech Beginner Night: Reviewing Records -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Recovering the Meaning of Baptism in Westminster Calvinism in Critical Dialogue with Thomas F. Torrance John Andrew Scott Doctor of Philosophy University of Edinburgh 2015 Declaration I declare that this thesis has been composed by myself, and that the work herein contained is my own. I, furthermore, hereby indicate that this thesis does not include work submitted for any other academic degree or professional qualification Signed Rev Dr John Andrew Scott January 2015 Abstract This thesis examines and critiques the doctrine of baptism in the theology of Thomas Torrance and utilises aspects of Torrance’s doctrine to recover and enrich the meaning of baptism in Westminster theology. Torrance’s doctrine of baptism has suffered from misunderstanding and has been widely neglected. This arises from Torrance introducing a new soteriological paradigm, that is claimed by Torrance, to be both new, and at the same time to be a recovery of the work of the early church fathers and Calvin. -

The Mormon Colonies in Chihuahua After the 1912 Exodus

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 29 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-1954 The Mormon Colonies in Chihuahua after the 1912 Exodus Elizabeth H. Mills Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Mills, Elizabeth H.. "The Mormon Colonies in Chihuahua after the 1912 Exodus." New Mexico Historical Review 29, 3 (1954). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol29/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Iff W 1'1 Ell CO 72 . I!! .. ·:'"'.1 P..,t....... J, _.J I ( I ' "v', \ I ' I THE MORMON COLONIES NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW VoL. xxtx JULY, 1954 No.3 THE MORMON COLONIES IN CHIHUAHUA AFTER THE 1912 EXODUS * By ELIZABETH H. MILLS Introduction N the spring of 1846 the Mormons trekked across the I plains from Nauvoo, Illinois, to the Great Salt Lake Basin, then a part of Mexico, for persecution of the Mor- . mons· in Illinois had led to the decision of their leader, Brigham Young, to seek a land where they .would be free to practice their religion in peace., Here the Mormons pros pered and gradually extended their colonies to the neighbor ing territories. Their original numb_ers were augmented by the immigration of converts from Europe and from Great Britain. By 1887 it was estimated that more than 85,000 immigrants had entered the Great Basin as a result of for eign missionary work, one of the strong features of the Mormon religion.1 The early Mormon colonies in Utah, largely agricultural, were distinguished by the efficient organization of the church and by a spirit of cooperation among the colonists. -

Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite!

Vote for a Socialist America! Vote for Dobbs and Carlson! Workers of the World, Unite! THE WALL STREET MEN AROUND TRUMAN — See Page 4 — THE MILITANT PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY OCTOBER 4, 1948 Vol. X II -.No. 40 267 PRICE: FIVE CENTS DOBBS, CARLSON LASH WAR <yMONGERS ;$WP flection New* DOBBS RECALLS FI6HT Bp-Partisan Duet flj Demand Popular Referendum OF DEBS AGAINST WAR On Issue o f W ar or Peace By FARRELL DOBBS and GRACE CARLSON IN CANTON RADIO TALK SWP Presidential and Vice-Presidential Candidates The following speech was broadcast to the workers of Can The United Nations is meeting in Paris in an ominous atmos- phere. The American imperialists have had the audacity to ton, Ohio, by Farrell Dobbs, SWP presidential candidate, over By George Clarke launch another war scare a bare month before the voters go to the Mutual network station WHKK on Friday, Sept. 24 from the polls. The Berlin dispute has been thrown into the Security SWP Campaign Manager 4 :45 to 5 p.m. The speech, delivered on the thirtieth anniversary Council; and the entire capitalist press, at this signal, has cast Grace Carlson got the kind of of Debs’ conviction for his Canton speech, demonstrates how aside all restraint in pounding the drums of war. welcome-home reception when she the SWP continues the traditions of the famous socialist agitator. The insolence of the Wan Street rulers stems from their assur arrived in Minneapolis on Sept. ance that they w ill continue to monopolize the government fo r 21 that was proper and deserving another four years whether Truman or Dewey sits in the White fo r the only woman candidate fo r Introduction by Ted Selander, Ohio State Secretary of the House. -

The Mormons Are Coming- the LDS Church's

102 Mormon Historical Studies Nauvoo, Johann Schroder, oil on tin, 1859. Esplin: The Mormons are Coming 103 The Mormons Are Coming: The LDS Church’s Twentieth Century Return to Nauvoo Scott C. Esplin Traveling along Illinois’ scenic Highway 96, the modern visitor to Nauvoo steps back in time. Horse-drawn carriages pass a bustling blacksmith shop and brick furnace. Tourists stroll through manicured gardens, venturing into open doorways where missionary guides recreate life in a religious city on a bend in the Mississippi River during the mid-1840s. The picture is one of prosper- ity, presided over by a stately temple monument on a bluff overlooking the community. Within minutes, if they didn’t know it already, visitors to the area quickly learn about the Latter-day Saint founding of the City of Joseph. While portraying an image of peace, students of the history of Nauvoo know a different tale, however. Unlike other historically recreated villages across the country, this one has a dark past. For the most part, the homes, and most important the temple itself, did not peacefully pass from builder to pres- ent occupant, patiently awaiting renovation and restoration. Rather, they lay abandoned, persisting only in the memory of a people who left them in search of safety in a high mountain desert more than thirteen hundred miles away. Firmly established in the tops of the mountains, their posterity returned more than a century later to create a monument to their ancestral roots. Much of the present-day religious, political, economic, and social power of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints traces its roots to Nauvoo, Illinois. -

The Mormon Trail

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 The Mormon Trail William E. Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hill, W. E. (1996). The Mormon Trail: Yesterday and today. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MORMON TRAIL Yesterday and Today Number: 223 Orig: 26.5 x 38.5 Crop: 26.5 x 36 Scale: 100% Final: 26.5 x 36 BRIGHAM YOUNG—From Piercy’s Route from Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Valley Brigham Young was one of the early converts to helped to organize the exodus from Nauvoo in Mormonism who joined in 1832. He moved to 1846, led the first Mormon pioneers from Win- Kirtland, was a member of Zion’s Camp in ter Quarters to Salt Lake in 1847, and again led 1834, and became a member of the first Quo- the 1848 migration. He was sustained as the sec- rum of Twelve Apostles in 1835. He served as a ond president of the Mormon Church in 1847, missionary to England. After the death of became the territorial governor of Utah in 1850, Joseph Smith in 1844, he was the senior apostle and continued to lead the Mormon Church and became leader of the Mormon Church. -

Adam Samuel Bennion, Superintendent of LDS Education - 1919-1928

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1969 Adam Samuel Bennion, Superintendent of LDS Education - 1919-1928 Kenneth G. Bell Sr. Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Bell, Kenneth G. Sr., "Adam Samuel Bennion, Superintendent of LDS Education - 1919-1928" (1969). Theses and Dissertations. 4517. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4517 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ADAM SAMUEL BENNION superintendent OF LDS EDUCATION 1919 TO 1928 daadna000 A thesis presented to the department of graduate studies in the college of religious instruction brigham young university in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of religious education by kenneth G bell august 19692969 acknowledgmentsacknowledgements the writerwriters who is indebted to many 9 gratefully and sincerely acknowledges the most helpful assistance rendered by dr james R clark as cammicommicommitteetteeatee chairman his scholarly insight and ttimelynelymely suggestsuggestionsions were most helpfulhelheihelpfulgpfulg also to drdro richard 000oo cowan for his suggestions as a member of the committecommitteecommitteescommitteejej to -

WILLIAM M. MAJOR: Brigham Young, Mary Ann Angel Young and Family HASELTINE: Mormons and the Visual Arts/25

JOHN HAFEN: Pasture WILLIAM M. MAJOR: Brigham Young, Mary Ann Angel Young and Family HASELTINE: Mormons and the Visual Arts/25 Fine Arts Center at Brigham Young University. Art thrives by its separate dignity, not by being made part of an open lobby. When art is finally liberated from the society and entertainment sections of newspapers, and when it comes off the walls of converted tearooms, top floors, or basements of other structures and is installed in a properly designed, humidity-controlled, air-conditioned, properly lighted modern museum, then shall we have come of age in the arts. And then, we can hope, the rich collections of Brigham Young University will have the professional attention — documentation, interpretation, exhibition, and conservation — they deserve. It is all very well to say that art should be integrated with life. That it should. But the scholarly responsibilities must be met if the culture is to be more than a superficial or transitory one. The quixotic remark of the contemporary American painter, Ad Reinhardt, "Art is art and everything else is everything else," has much relevance. Another hinderance to the full development of art in Utah, one which has most likely been influenced by Mormon attitudes, is the denial of the use of the nude model in all but one of the art depart- ments of our institutions of higher learning, although other educa- tional institutions have sporadically employed nude models, for instance, Brigham Young University, for a brief period in the late 1930's. How preposterous such proscription can be is best illustrated by a recent student exhibition of figure drawings, arranged by an art professor in one of Utah's universities. -

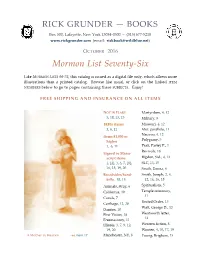

Mormon List 76

RICK GRUNDER — BOOKS Box 500, Lafayette, New York 13084‐0500 – (315) 677‐5218 www.rickgrunder.com (email: [email protected]) OCTOBER 2016 Mormon List Seventy‐Six Like MORMON LISTS 66‐75, this catalog is issued as a digital file only, which allows more illustrations than a printed catalog. Browse like usual, or click on the linked ITEM NUMBERS below to go to pages containing these SUBJECTS. Enjoy! FREE SHIPPING AND INSURANCE ON ALL ITEMS NOT IN FLAKE Martyrdom, 4, 12 5, 10, 13, 15 Military, 9 1830s items Missouri, 4, 12 3, 6, 11 Mor. parallels, 11 Nauvoo, 4, 12 Items $1,000 or Polygamy, 5 higher 1, 6, 11 Pratt, Parley P., 1 Revivals, 18 Signed or Manu‐ script items Rigdon, Sid., 4, 12 1, [2], 3, 6, 7, [8], SLC, 13, 15 16, 18, 19, 20 Smith, Emma, 6 Broadsides/hand‐ Smith, Joseph, 2, 4, bills, 10, 13 12, 14, 16, 18 Animals, stray, 6 Spiritualism, 5 California, 10 Temple ceremony, 11 Canals, 7 United Order, 13 Carthage, 12, 20 Watt, George D., 13 Danites, 10 First Vision, 18 Wentworth letter, 14 Freemasonry, 11 Illinois, 3, 7, 9, 12, Western fiction, 8 19, 20 Women, 4, 10, 17, 19 A Mother in Heaven see item 17 Manchester, NY, 6 Young, Brigham, 13 the redoubtable Origen Bachelor – Givens & Grow 1 BACHELER, Origen. Excellent AUTOGRAPH LETTER SIGNED AND INITIALED, to Rev. Orange SCOTT (in New York City). Providence, R[hode]. I[sland]., January 5, 1846. 25 X 19½ cm. 3 pages on two conjugate leaves. Folded stamp‐ less letter with address portion and recipientʹs docket on the outside page. -

Appendix 1 Andrew Jenson, Mormon Encyclopedist Davis Bitton and Leonard J

Appendix 1 Andrew Jenson, Mormon Encyclopedist Davis Bitton and Leonard J. Arrington In November 1876, shortly after the appearance of Edward Tullidge’s zealous collector of historical records, faithful diarist, and author of Life of Brigham Young; Or, Utah and Her Founders, a twenty-six-year- more than five thousand published biographical sketches. Jenson may old Danish settler in Pleasant Grove, Utah, wrote to Daniel H. Wells, have contributed more to preserving the factual details of Latter-day a close adviser to Brigham Young. Hopeful that he would not have to Saint history than any other person; at least for sheer quantity, his spend the rest of his life as a manual laborer, the young man asked if projects will likely remain unsurpassed. Jenson’s industry, persistence, he might have permission to prepare and publish a history of Joseph and dogged determination in the face of rebuffs and disappointments Smith in the Danish language. Wells replied that he had “no hesi- have caused every subsequent Mormon historian to be indebted to him. tancy” in approving the proposal but doubted that the project, although Andreas Jensen was born in 1850 in the country village of Damgren, worthwhile, would be financially remunerative. The young immigrant in Torslev Parish, Hjørring County, Jutland, Denmark, the second son arranged his affairs at home, began the work of translating and writing, of Danish peasants.1 When Andreas was four, his parents were visited and canvassed for subscribers. by Mormon missionaries in Denmark and converted. Andreas and his Thus began the historical labors of Andrew Jenson, who for the older brother, Jens, who were subjected to harassment at school because next sixty-five years worked prodigiously in the cause of Mormon his- 1. -

Defending Mormonism: the Scandinavian Mission Presidency of Andrew Jenson, 1909–12

Go Ye into All the World Alexander L. Baugh 14 Defending Mormonism: The Scandinavian Mission Presidency of Andrew Jenson, 1909–12 n December 9, 1908, assistant Church historian Andrew Jenson received Oa letter from Joseph F. Smith, John R. Winder, and Anthon H. Lund, the Church’s First Presidency, notifying him of his appointment to preside over the Scandinavian Mission, headquartered in Copenhagen, Denmark, where he would replace Søren Rasmussen, who had been serving as president since November 1907. It is not known if Jenson anticipated receiving the call, but he accepted the call in spite of the many responsibilities associated with his work in the Historian’s Office. It was expected that he would leave as soon as he could get his affairs in order. The next five weeks were busy ones for the newly called mission president, both at the Historian’s Office and at home. In addition, he set aside time to visit family members and acquaintances and enjoyed farewell dinners and social get-togethers hosted by well-wishers. President Joseph F. Smith formally set apart Andrew Jenson on January 12, 1909. Five days later, Jenson delivered a farewell address to Alexander L. Baugh is a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University. Go Ye into All the World a large congregation in the Salt Lake Tabernacle. The following day, January 18, at the Salt Lake train depot, he said his last good-byes to his two wives, Emma and Bertha (the two women were sisters), his immediate family, his colleagues, and Church officials and boarded an eastbound train.