The First Circle: Transcription and Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laurence Hobgood

Laurence Hobgood "One of the *inest pianists out there. Period." --All About Jazz “ . one of the most incredible pianists I’ve ever heard.” --Dave Brubeck "Welcome to a new piano star . Laurence Hobgood . --The Independent (UK) Best known for his collaboration with vocalist Kurt Elling, multiple Grammy-nominee and 2010 Grammy-winner Laurence Hobgood has enjoyed a multi-faceted and dynamic career. Musical Director for Elling since 1995, he’s played on, composed, arranged and co-produced all of Elling’s CDs (six for Blue Note and three for Concord), each Grammy- nominated. 2009’s Dedicated To You: Kurt Elling Sings The Music Of Coltrane and Hartman, recorded live at Lincoln Center, won the 2010 Grammy Award for Best Vocal Jazz Record. Hobgood began formal piano study at age six in Dallas, Texas, where his father was Chairman of the Southern Methodist University theatre program. At age 12, he was introduced to gospel and blues through his family's church. Several years later, after moving to Illinois, he began formal training in jazz. He attended the University of Illinois, where he played for three years in the "A" jazz ensemble led by John Garvey. During that time his classical study continued with Ian Hobson. After moving to Chicago in 1988, he established a local presence leading his own quintet and joining forces with some of Chicago's premier players, including Ed Peterson, Fareed Haque, and most importantly seven-time Grammy Award-winning drummer, Paul Wertico. The group, Trio New, with Hobgood, Wertico, and bassist Eric Hochberg, played to critical acclaim and established a serious connection with Wertico that spans many projects and ensembles. -

Contact: Lydia Penningroth [email protected] 312-957-0000

Contact: Lydia Penningroth [email protected] 312-957-0000 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Chicago Philharmonic Chamber Players Present the Best of Gershwin and Bernstein Chicago, IL – (January 5, 2017) The Chicago Philharmonic Chamber Players (cp2) explore iconic Broadway classics and early cinema hits by Gershwin, Bernstein, Kerns, Rogers and Hammerstein, Cole Porter, and more at City Winery Chicago (1200 W Randolph St, Chicago.) An accomplished, inventive cp2 quintet performs selections from the beloved American hits such as “Porgy and Bess” and “West Side Story.” Doors open at 11:00 A.M., and brunch will be available for purchase before and during the performance. Casual attire is encouraged. Broadway on Randolph Music of Gershwin and Bernstein Sunday, January 15, 2017, Noon City Winery Chicago (1200 W Randolph St, Chicago) Bill Denton, trumpet Ed Harrison, vibraphone and percussion Pete Labella, piano Collins Trier, bass Eric Millstein, drums “Different Folks” is the first concert in the Chicago Philharmonic Chamber Players (cp2) Spring 2017 Series at City Winery Chicago. Other concerts in this series include Sounds of Change (February 19) and Mozart & Mimosas (March 19). About The Chicago Philharmonic Society The Chicago Philharmonic Society is a collaboration of over 200 of the highest-level classical musicians performing in the Chicago metropolitan area. Governed under a groundbreaking structure of musician leadership, the Society presents concerts at venues throughout the Chicago area that cover the full spectrum of classical music, from Bach to Britten and beyond. The Society’s orchestra, known simply as the Chicago Philharmonic, has been called “one of the country’s finest symphonic orchestras” (Chicago Tribune), and its unique chamber music ensembles, which perform as the Chicago Philharmonic Chamber Players (cp2), draw from its vast pool of versatile musicians. -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

Facultad De Artes Y Humanidades Carrera De

FACULTAD DE ARTES Y HUMANIDADES CARRERA DE MÚSICA TEMA: Composición y creación de arreglos en formato bajo y voz con la aplicación de los recursos orquestales y de ejecución de Pedro Aznar y Andrés Rotmitrovsky. AUTOR: Decker Del Pino, Carlos Andrés Trabajo de titulación previo a la obtención del título de LICENCIADO EN MÚSICA TUTOR: Mora Cobo, Alex Fernando Guayaquil, Ecuador 20 de septiembre de 2018 FACULTAD DE ARTES Y HUMANIDADES CARRERA DE MÚSICA CERTIFICACIÓN Certificamos que el presente trabajo de titulación, fue realizado en su totalidad por Decker Del Pino, Carlos Andrés, como requerimiento para la obtención del título de Licenciado en música. TUTOR f. ______________________ Mora Cobo, Alex Fernando DIRECTOR DE LA CARRERA f. ______________________ Vargas Prías, Gustavo Daniel FACULTAD DE ARTES Y HUMANIDADES CARRERA DE MÚSICA DECLARACIÓN DE RESPONSABILIDAD Yo, Decker Del Pino, Carlos Andrés DECLARO QUE: El Trabajo de Titulación Composición y creación de arreglos en formato bajo y voz con la aplicación de los recursos orquestales y de ejecución de Pedro Aznar y Andrés Rotmitrovsky, previo a la obtención del título de Licenciado en música, ha sido desarrollado respetando derechos intelectuales de terceros conforme las citas que constan en el documento, cuyas fuentes se incorporan en las referencias o bibliografías. Consecuentemente este trabajo es de mi total autoría. En virtud de esta declaración, me responsabilizo del contenido, veracidad y alcance del Trabajo de Titulación referido. Guayaquil, 20 de septiembre del 2018 EL AUTOR -

Jazz Collection: Lyle Mays

Jazz Collection: Lyle Mays Dienstag, 19. November 2013, 21.00 - 22.00 Uhr Samstag, 23. November 2013, 22.00 - 24.00 Uhr (Zweitsendung) Ohne ihn wäre der Gitarrist Pat Metheny nicht, was er heute ist: Lyle Mays ist seit den Anfängen der Pat Metheny Group mit dabei, ist Ko-Autor der allermeisten Stücke dieser weltberühmten Fusion-Band und nie richtig aus dem Schatten von Strahlemann Metheny herausgekommen. Wer je von der Pat Metheny Group gehört hat, der kennt Lyle Mays: der Pianist, Keyboarder und Komponist ist die rechte Hand von Pat Metheny. Er hat praktisch alle wichtigen Stücke dieser weltberühmten Band mit Metheny zusammen komponiert - und ist dennoch immer im Schatten von Metheny geblieben. Dabei beherrscht Lyle Mays das ganze Spektrum von elektronischen Soundteppichen bis zum makellosen akustischen Piano-Jazz perfekt. Wie ist Lyle Mays zu einem solchen musikalischen Tausendsassa geworden? Und warum wird er als Komponist ständig etwas unterschätzt? Immanuel Brockhaus ist Gast von Jodok Hess. Lab `75: Lab `75 LP NTSU LJ108 Track 2: Ouverture to the Royal Mongolian Suma Foosball Festival Pat Metheny: As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls CD ECM 1190 Track 2: Ozark Pat Metheny Group: Offramp CD ECM 1216 Track 6: James Lyle Mays Trio: Fictionary CD Geffen GED24521 Track 9: Falling Grace Lyle Mays: Solo (Improvisations For Expanded Piano) CD Warner Bros. 47284 Track 10: Long Life Pat Metheny Group: Speaking Of Now CD Warner Bros 48025 Track 2: Proof Bonustracks – nur in der Samstagsausgabe Pat Metheny Group: Pat Metheny Group CD ECM Track 6: Lone Jack Track 1: San Lorenzo Pat Metheny Group: American Garage CD ECM Track 6: Cross the Heartland Track 4: American Garage Lyle Mays: Street Dreams CD Geffen Records Track 3: Chorinho Track 4: Possible Straight Joni Mitchel: Shadows and Light CD Elektra Track 5: Good Bye Poork-Pie Hat Track 9: Hejira Lyle Mays: Solo (Improvisations For Expanded Piano) CD Warner Bros. -

Pat Metheny 80/81 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Pat Metheny 80/81 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: 80/81 Country: Japan Released: 1980 Style: Post Bop, Contemporary Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1322 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1569 mb WMA version RAR size: 1314 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 404 Other Formats: AU RA MP1 MIDI AHX MOD MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Two Folk Songs 1st 1 13:17 Composed By – Pat Metheny 2nd 2 7:31 Composed By – Charlie Haden - 80/81 3 7:28 Composed By – Pat Metheny The Bat 4 5:58 Composed By – Pat Metheny Turnaround 5 7:05 Composed By – Ornette Coleman Open 6 Composed By – Haden*, Redman*, DeJohnette*, Brecker*, Metheny*Composed 14:25 By [Final Theme] – Pat Metheny Pretty Scattered 7 6:56 Composed By – Pat Metheny Every Day (I Thank You) 8 13:16 Composed By – Pat Metheny Goin' Ahead 9 3:56 Composed By – Pat Metheny Companies, etc. Recorded At – Talent Studio Lacquer Cut At – PRS Hannover Credits Bass – Charlie Haden Design – Barbara Wojirsch Drums – Jack DeJohnette Engineer – Jan Erik Kongshaug Guitar – Pat Metheny Photography By [Back] – Dag Alveng Photography By [Inside] – Rainer Drechsler Producer – Manfred Eicher Tenor Saxophone – Dewey Redman (tracks: B1, B2, C1, C2), Mike Brecker* (tracks: A1, A2, B2, C1, C2, D1) Notes Recorded May 26-29, 1980 at Talent Studios, Oslo. An ECM Production. ℗ 1980 ECM Records GmbH. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 042281557941 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year ECM 1180/81, 80/81 (2xLP, ECM Records, ECM 1180/81, Pat Metheny Germany 1980 2641 180 Album) ECM Records -

0A7aa945006f6e9505e36c8321

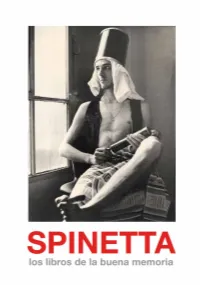

2 4 Spinetta. Los libros de la buena memoria es un homenaje a Luis Alberto Spinetta, músico y poeta genial. La exposición aúna testimonios de la vida y obra del artista. Incluye un conjunto de manuscritos inéditos, entre los que se hallan poesías, dibujos, letras de canciones, y hasta las indicaciones que le envió a un luthier para la construcción de una guitarra eléctrica. Se exhibe a su vez un vasto registro fotográfico con imágenes privadas y profesionales, documentales y artísticas. Este catálogo concluye con la presentación de su discografía completa y la imagen de tapa de su único libro de poemas publicado, Guitarra negra. Se incluyen también dos escritos compuestos especialmente para la ocasión, “Libélulas y pimientos” de Eduardo Berti y “Eternidad: lo tremendo” de Horacio González. 5 6 Pensé que habías salido de viaje acompañado de tu sombra silbando hablando con el sí mismo por atrás de la llovizna... Luis Alberto Spinetta, Guitarra negra,1978 Niño gaucho. 23 de enero de 1958 7 Spinetta. Santa Fe, 1974. Fotografía: Eduardo Martí 8 Eternidad: lo tremendo por Horacio González Llamaban la atención sus énfasis, aunque sus hipérboles eran dichas en tono hu- morístico. Quizás todo exceso, toda ponderación, es un rasgo de humor, un saludo a lo que desearíamos del mundo antes que la forma real en que el mundo se nos da. Había un extraño recitado en su forma de hablar, pero es lógico: también en su forma de cantar, siempre con una resolución final cercana a la desesperación. Un plañido retenido, insinuado apenas, pero siempre presente. ¿Pero lo definimos bien de este modo? ¿No es todo el rock, “el rock del bueno”, como decía Fogwill, completamente así? Quizás esa cauta desesperación de fondo precisaba de un fraseo que recubría todo de un lamento, con un cosquilleo gracioso. -

Pilgrimage Review Dan Ouellette Stereophile.Pdf

Stereophile: Recording of May 2007: <I>Pilgrimage</I> pagina 1 van 3 Stereophile :: Home Theater :: Ultimate AV :: Audio Video Interiors :: Shutterbug :: Home Entertainment Show Recording of May 2007: Pilgrimage Your E-mail Dan Ouellette, May, 2007 Zip Code Michael Brecker Pilgrimage Michael Brecker, tenor sax, EWI; Pat Metheny, guitars; Herbie Hancock, Brad Mehldau, keyboards; John Patitucci, bass; Jack DeJohnette, drums Ads by Google Heads Up International HUCD 3095 (CD). 2007. Michael Brecker, Gil Goldstein, Steve Rodby, Pat Metheny, prods.; Darryl Pitt, exec. prod.; Joe Ferla, eng. DDD. TT: 77:57 Study Jazz Improv Online Performance ****½ Online jazz improvisation courses and programs Sonics ****½ from Berklee College. www.berkleemusic.com When, following the superb Wide Angels (2003), recorded with his 15-piece Quindectet, Michael Brecker decided to end his long-term contract with Impulse!/Verve and hook up with Heads Brilliant Jazz Up International, part of his goal was to Alle prachtige jazzmuziek van dit label is hier adventurously expand his repertoire in a jazz direction more oriented toward world verkrijgbaar! music—specifically, an album influenced www.Kruidvat.nl/jazz by Bulgarian music, which had forced him to harmonically reconceptualize how he played his tenor sax. However, his Bulgarian speed-jazz project, which was to include Bulgarian artists, was shelved in 2005 when Brecker was stricken with the rare bone-marrow cancer > Recent Additions Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), which > Budget Components > Floorstanding Loudspeakers -

PROGRAM NOTES Guided Tour

13/14 Season SEP-DEC Ted Kurland Associates Kurland Ted The New Gary Burton Quartet 70th Birthday Concert with Gary Burton Vibraphone Julian Lage Guitar Scott Colley Bass Antonio Sanchez Percussion PROGRAM There will be no intermission. Set list will be announced from stage. Sunday, October 6 at 7 PM Zellerbach Theatre The Annenberg Center's Jazz Series is funded in part by the Brownstein Jazz Fund and the Philadelphia Fund For Jazz Legacy & Innovation of The Philadelphia Foundation and Philadelphia Jazz Project: a project of the Painted Bride Art Center. Media support for the 13/14 Jazz Series provided by WRTI and City Paper. 10 | ABOUT THE ARTISTS Gary Burton (Vibraphone) Born in 1943 and raised in Indiana, Gary Burton taught himself to play the vibraphone. At the age of 17, Burton made his recording debut in Nashville with guitarists Hank Garland and Chet Atkins. Two years later, Burton left his studies at Berklee College of Music to join George Shearing and Stan Getz, with whom he worked from 1964 to 1966. As a member of Getz's quartet, Burton won Down Beat Magazine's “Talent Deserving of Wider Recognition” award in 1965. By the time he left Getz to form his own quartet in 1967, Burton had recorded three solo albums. Borrowing rhythms and sonorities from rock music, while maintaining jazz's emphasis on improvisation and harmonic complexity, Burton's first quartet attracted large audiences from both sides of the jazz-rock spectrum. Such albums as Duster and Lofty Fake Anagram established Burton and his band as progenitors of the jazz fusion phenomenon. -

"¿Porqué Este Genio No Domina Todavía El Mundo De La Música?"

CONCIERTO DE VITOR RAMIL El productor londinense John Armstrong dijo: "¿Porqué este genio no domina todavía el mundo de la música?" DOMINGO 23 DE NOVIEMBRE, 19H Entrada 8 € anticipada y amigos CAT i Amigos CAMEC / 10 € taquilla Centre Artesà Tradicionàrius, Plaça Anna Franck s/n, Barcelona VENDA ANTICIPADA https://www.codetickets.com/cat-centre-artesa-tradicionarius/ca/codetickets.com/128/ Vitor Ramil es uno de los más relevantes cantautores brasileños de la actualidad. Ha resignificado la música del sur de Brasil, alimentada con ritmos y temáticas cercanas a Uruguay y Argentina en torno a la idea del ' Templadismo ' en oposición al Tropicalismo 'de Brasil más conocido. Sus temas han sido grabados por Mercedes Sosa, Milton Nascimento, Ney Matogrosso, Caetano Veloso y Gal Costa, autor de la música de '12 segundos de oscuridad ', canción que abre el disco homónimo de Jorge Drexler. En 2011 ganó el Premio de la Música Brasileña como Mejor Cantante. En este concierto coproducido entre HAMACAS-Casa América Cataunya y Centro Artesano Tradicionàrius presentará un repertorio de sus dos últimos discos: 'Délibáb' y 'Foi no más que hicimos'. Links Programa ‘Encuentro en el estudio’ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cKZbFrTHgFg Último disco 'Foi No més que Vem' (2013) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DuZTHeL5VCk VITOR RAMIL Compositor, cantante, instrumentista y escritor, es autor de nueve discos, tres novelas y un ensayo. Nació y vive en el estado de Rio Grande do Sul, en el extremo sur de Brasil. Grabó su primer disco a los 18 años. Desde entonces ha lanzado A Paixao de V segundo ela proprio, Tango, À beca, Ramilonga - A estética do friío -, Tambong, longes, Satolep Sambatown y Délibáb. -

Bird's Bebop Brother Goes Home

gram JAZZ PROMOTING AND NURTURING JAZZ IN CHICAGO SEPTEMBER 2020 WWW.JAZZINCHICAGO.ORG BIRD’S BEBOP BROTHER GOES HOME JOE SEGAL, JIC CO-FOUNDER, 2015 NEA JAZZ MASTER, REMEMBERED BY MUSICIANS AND MUSIC LOVERS BY COREY HALL While our current reality resembles Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds on steroids, let us escape and celebrate Joe Segal -- April 24, 1926-August 10, 2020 -- who brought jazz to Chicago for more than seven decades. Imagine… Scene: August 10, 2020. Place: Tadd’s Hot House. Charlie Parker, firm, fit, and poison-free since March 12, 1955, is sheddin’ “Just Friends” when in walks Joe. “Hey, man! It’s about time!” Bird exclaims, embracing his brother in bop. “What were you up to? Reading the list of upcoming cats?” “I was busy saving the youth,” Joe replies, while readjusting his Cubs cap. “Keeping them safe from the ‘Yookey Dukes!’” Both brothers laugh, embrace again, and then cast their sights down at this page, now a stage, where dudes and dudettes carrying voices, horns and guitars gather to take on this thought prompter: “What song sums up your experience with and/or appreciation of Joe Segal?” (The tunes designated with an asterisk are accompanied by a video available by clicking on the link or thumbnail). Solitaire Anna Miles, vocalist: (*) “I did every gig at the Jazz Showcase with Willie Pickens. We always opened with “Exactly Like You," and if Joe was there, he would sing it with me from the audience, so I think he liked the tune…or at least the way Willie and I did it. -

JAZZIZ-Metheny-Interviews.Pdf

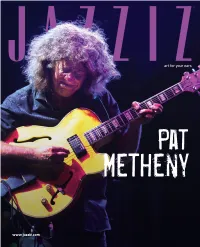

Pat Metheny www.jazziz.com JAZZIZ Subscription Ad Lage.pdf 1 3/21/18 10:32 AM Pat Metheny Covered Though I was a Pat Metheny fan for nearly a decade before I special edition, so go ahead and make fun if you please). launched JAZZIZ in 1983, it was his concert, at an outdoor band In 1985, we published a cover story that included Metheny, shell on the University of Florida campus, less than a year but the feature was about the growing use of guitar synthesizers before, that got me to focus on the magazine’s mission. in jazz, and we ran a photo of John McLaughlin on the cover. As a music reviewer for several publications in the late Strike two. The first JAZZIZ cover that featured Pat ran a few ’70s and early ’80s, I was in touch with ECM, the label for years later, when he recorded Song X with Ornette Coleman. whom Metheny recorded. It was ECM that sent me the press When the time came to design the cover, only photos of Metheny credentials that allowed me to go backstage to interview alone worked, and Pat was unhappy with that because he felt Metheny after the show. By then, Metheny had recorded Ornette should have shared the spotlight. Strike three. C around 10 LPs with various instrumental lineups: solo guitar, A few years later, I commissioned Rolling Stone M duo work with Lyles Mays on the chart-topping As Wichita Fall, photographer Deborah Feingold to do a Metheny shoot for a Y So Falls Wichita Falls, trio, larger ensembles and of course his Pat cover story that would delve into his latest album at the time.