INVASIVE INSECTS Risks and Pathways Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cycad Aulacaspis Scale

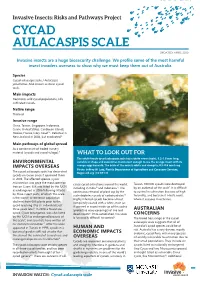

Invasive Insects: Risks and Pathways Project CYCAD AULACASPIS SCALE UPDATED: APRIL 2020 Invasive insects are a huge biosecurity challenge. We profile some of the most harmful insect invaders overseas to show why we must keep them out of Australia. Species Cycad aulacaspis scale / Aulacaspis yasumatsui. Also known as Asian cycad scale. Main impacts Decimates wild cycad populations, kills cultivated cycads. Native range Thailand. Invasive range China, Taiwan, Singapore, Indonesia, Guam, United States, Caribbean Islands, Mexico, France, Ivory Coast1,2. Detected in New Zealand in 2004, but eradicated.2 Main pathways of global spread As a contaminant of traded nursery material (cycads and cycad foliage).3 WHAT TO LOOK OUT FOR The adult female cycad aulacaspis scale has a white cover (scale), 1.2–1.6 mm long, ENVIRONMENTAL variable in shape and sometimes translucent enough to see the orange insect with its IMPACTS OVERSEAS orange eggs beneath. The scale of the male is white and elongate, 0.5–0.6 mm long. Photo: Jeffrey W. Lotz, Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, The cycad aulacaspis scale has decimated Bugwood.org | CC BY 3.0 cycads on Guam since it appeared there in 2003. The affected species, Cycas micronesica, was once the most common cause cycad extinctions around the world, Taiwan, 100,000 cycads were destroyed tree on Guam, but was listed by the IUCN 7 including in India10 and Indonesia11. The by an outbreak of the scale . It is difficult as endangered in 2006 following attacks continuous removal of plant sap by the to control in cultivation because of high by three insect pests, of which this scale scale depletes cycads of carbohydrates4,9. -

Survival of the Cycad Aulacaspis Scale in Northern Florida During Sub-Freezing Weather

furcata) (FDACS/DPI, 2002). These thrips are foliage feeders North American Plant Protection Organization’s Phytosanitary causing galling and leaf curl, which is cosmetic and has not Alert System been associated with plant decline. This feeding damage is http://www.pestalert.org only to new foliage and appears to be seasonal. This pest is be- coming established in urban areas causing concern to home- Literature Cited owners and commercial landscapers due to leaf damage. Control is difficult due to protection by leaf galls. Howev- Edwards, G. B. 2002. Pest Alert, Holopothrips sp., an Introduced Thrips Pest er, systemic insecticides are providing some control. No bio- of Trumpet Tree. March 2002. <http://doacs.state.fl.us/~pi/enpp/ ento/images/paholo-pothrips3.02.gif>. controls have been found. FDACS/DPI. 2002. TRI-OLOGY. Mar.-Apr. 2002. Fla. Dept. Agr. Cons. Serv./ Div. Plant Ind. Newsletter, vol. 41, no. 2. <http://doacs.state.fl.us/~pi/ Resources for New Insect Pest Information enpp/02-mar-apr.html>. Howard, F. W., A. Hamon, G. S. Hodges, C. M. Mannion, and J. Wofford. 2002. Lobate Lac Scale, Paratachardina lobata lobata (Chamberlin) (Hemip- The following are some web sites and list serves for addi- tera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea: Kerriidae). Univ. of Fla. Cir., EENY- tional information on new insects pests in Florida. 276. <http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IN471>. Hoy, M. A., A. Hamon, and R. Nguyen. 2003. Pink Hibiscus Mealybug, Ma- University of Florida Pest Alert conellicoccus hirsutus (Green) (Insecta: Homoptera: Pseudococcidae). http://extlab7.entnem.ufl.edu/PestAlert/ Univ. of Fla. Cir., EENY-29. <http://creatures.ifas.ufl.edu/orn/mealybug/ mealybug.htm>. -

Report and Recommendations on Cycad Aulacaspis Scale, Aulacaspis Yasumatsui Takagi (Hemiptera: Diaspididae)

IUCN/SSC Cycad Specialist Group – Subgroup on Invasive Pests Report and Recommendations on Cycad Aulacaspis Scale, Aulacaspis yasumatsui Takagi (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) 18 September 2005 Subgroup Members (Affiliated Institution & Location) • William Tang, Subgroup Leader (USDA-APHIS-PPQ, Miami, FL, USA) • Dr. John Donaldson, CSG Chair (South African National Biodiversity Institute & Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, Cape Town, South Africa) • Jody Haynes (Montgomery Botanical Center, Miami, FL, USA)1 • Dr. Irene Terry (Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) Consultants • Dr. Anne Brooke (Guam National Wildlife Refuge, Dededo, Guam) • Michael Davenport (Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Miami, FL, USA) • Dr. Thomas Marler (College of Natural & Applied Sciences - AES, University of Guam, Mangilao, Guam) • Christine Wiese (Montgomery Botanical Center, Miami, FL, USA) Introduction The IUCN/SSC Cycad Specialist Group – Subgroup on Invasive Pests was formed in June 2005 to address the emerging threat to wild cycad populations from the artificial spread of insect pests and pathogens of cycads. Recently, an aggressive pest on cycads, the cycad aulacaspis scale (CAS)— Aulacaspis yasumatsui Takagi (Hemiptera: Diaspididae)—has spread through human activity and commerce to the point where two species of cycads face imminent extinction in the wild. Given its mission of cycad conservation, we believe the CSG should clearly focus its attention on mitigating the impact of CAS on wild cycad populations and cultivated cycad collections of conservation importance (e.g., Montgomery Botanical Center). The control of CAS in home gardens, commercial nurseries, and city landscapes is outside the scope of this report and is a topic covered in various online resources (see www.montgomerybotanical.org/Pages/CASlinks.htm). -

Invasive Alien Species in Protected Areas

INVASIVE ALIEN SPECIES AND PROTECTED AREAS A SCOPING REPORT Produced for the World Bank as a contribution to the Global Invasive Species Programme (GISP) March 2007 PART I SCOPING THE SCALE AND NATURE OF INVASIVE ALIEN SPECIES THREATS TO PROTECTED AREAS, IMPEDIMENTS TO IAS MANAGEMENT AND MEANS TO ADDRESS THOSE IMPEDIMENTS. Produced by Maj De Poorter (Invasive Species Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission of IUCN - The World Conservation Union) with additional material by Syama Pagad (Invasive Species Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission of IUCN - The World Conservation Union) and Mohammed Irfan Ullah (Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, Bangalore, India, [email protected]) Disclaimer: the designation of geographical entities in this report does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, ISSG, GISP (or its Partners) or the World Bank, concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delineation of its frontiers or boundaries. 1 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...........................................................................................4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................................6 GLOSSARY ..................................................................................................................9 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................12 1.1 Invasive alien -

References, Sources, Links

History of Diaspididae Evolution of Nomenclature for Diaspids 1. 1758: Linnaeus assigned 17 species of “Coccus” (the nominal genus of the Coccoidea) in his Systema Naturae: 3 of his species are still recognized as Diaspids (aonidum,ulmi, and salicis). 2. 1828 (circa) Costa proposes 3 subdivisions including Diaspis. 3. 1833, Bouche describes the Genus Aspidiotus 4. 1868 to 1870: Targioni-Tozzetti. 5. 1877: The Signoret Catalogue was the first compilation of the first century of post-Linnaeus systematics of scale insects. It listed 9 genera consisting of 73 species of the diaspididae. 6. 1903: Fernaldi Catalogue listed 35 genera with 420 species. 7. 1966: Borschenius Catalogue listed 335 genera with 1890 species. 8. 1983: 390 genera with 2200 species. 9. 2004: Homptera alone comprised of 32,000 known species. Of these, 2390 species are Diaspididae and 1982 species of Pseudococcidae as reported on Scalenet at the Systematic Entomology Lab. CREDITS & REFERENCES • G. Ferris Armored Scales of North America, (1937) • “A Dictionary of Entomology” Gordh & Headrick • World Crop Pests: Armored Scale Insects, Volume 4A and 4B 1990. • Scalenet (http://198.77.169.79/scalenet/scalenet.htm) • Latest nomenclature changes are cited by Scalenet. • Crop Protection Compendium Diaspididae Distinct sexual dimorphism Immatures: – Nymphs (mobile, but later stages sessile and may develop exuviae). – Pupa & Prepupa (sessile under exuviae, Males Only). Adults – Male (always mobile). – Legs. – 2 pairs of Wing. – Divided head, thorax, and abdomen. – Elongated genital organ (long style & penal sheath). – Female (sessile under exuviae). – Legless (vestigial legs may be present) & Wingless. – Flattened sac-like form (head/thorax/abdomen fused). – Pygidium present (Conchaspids also have exuvia with legs present). -

The Biology and Ecology of Armored Scales

Copyright 1975. All rights resenetl THE BIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY +6080 OF ARMORED SCALES 1,2 John W. Beardsley Jr. and Roberto H. Gonzalez Department of Entomology, University of Hawaii. Honolulu. Hawaii 96822 and Plant Production and Protection Division. Food and Agriculture Organization. Rome. Italy The armored scales (Family Diaspididae) constitute one of the most successful groups of plant-parasitic arthropods and include some of the most damaging and refractory pests of perennial crops and ornamentals. The Diaspididae is the largest and most specialized of the dozen or so currently recognized families which compose the superfamily Coccoidea. A recent world catalog (19) lists 338 valid genera and approximately 1700 species of armored scales. Although the diaspidids have been more intensively studied than any other group of coccids, probably no more than half of the existing forms have been recognized and named. Armored scales occur virtually everywhere perennial vascular plants are found, although a few of the most isolated oceanic islands (e.g. the Hawaiian group) apparently have no endemic representatives and are populated entirely by recent adventives. In general. the greatest numbers and diversity of genera and species occur in the tropics. subtropics. and warmer portions of the temperate zones. With the exclusion of the so-called palm scales (Phoenicococcus. Halimococcus. and their allies) which most coccid taxonomists now place elsewhere (19. 26. 99). the armored scale insects are a biologically and morphologically distinct and Access provided by CNRS-Multi-Site on 03/25/16. For personal use only. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1975.20:47-73. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org homogenous group. -

Spent Coffee Grounds Do Not Control Cycad Aulacaspis Scale

undersides of leaves (Howard and Spent Coffee Grounds Do Not Control Cycad Weissling, 1999; Smith and Cave, Aulacaspis Scale 2006; Wiese et al., 2005) and roots (Howard et al., 1999; Weissling et al., 1999), which are difficult to cover Tracy Monique Magellan1, Chad Husby, Stella Cuestas, with foliar sprays (Hodges et al., and M. Patrick Griffith 2003; Smith and Cave, 2006). At Montgomery Botanical Center (MBC, Coral Gables, FL), research on ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. asian cycad scale, Aulacaspis yasumatsui, coffee beans, the control and integrated pest man- mulch, neem oil, orange oil, Coffea arabica, Cycas debaoensis, Cycas micronesica agement of CAS has been performed (Wiese and Mannion, 2007). Mannion SUMMARY. Cycad aulacaspis scale [CAS (Aulacaspis yasumatsui)] is a highly de- structive pest insect worldwide. CAS feeds on cycad (Cycas sp.) plantings and is also (2003) performed a study examining posing a problem for the foliage industry. The use of spent coffee grounds to possible chemical deterrents, many of prevent or control CAS has received increased popularity in the last few years. This which were not viable because of phy- study assesses whether the application of spent coffee grounds is a realistic control totoxicity. Experiments on biological method against CAS, and whether spent coffee grounds can be successfully used as control of CAS were also conducted at a natural alternative to chemical pesticides. Two tests were performed during MBC (Cave, 2006; Wiese and Mannion, Summer 2010 and 2011. The first experiment assessed seven treatments: five coffee 2007; Wiese et al., 2005). treatments, neem oil, and orange oil to control CAS on the debao cycad (Cycas Potential insecticidal activity of debaoensis). -

Aulacaspis Yasumatsui Takagi

Aulacaspis yasumatsui Takagi The Cycad Aulacaspis Scale (CAS), Aulacaspis yasumatsui, a native of Southeast Asia, is found on plants from the gymnosperm order Cycadales. Its preferred host belong to the genus Cycas. CAS is highly damaging to cycads, which include horticulturally important and endangered plant species. The scale has the potential to spread to new areas via plant movement in the horticulture trade. Its known introduced range includes some states in the USA including Florida and Hawai‘i, Cayman Is. Puerto Rico and Vieques Islands, US Virgin Islands, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Guam. CAS has been reported from the island of Rota (Northern Mariana Islands) in 2007 and Palau in 2008. or at the base of the petiole. Scales also infest the upper surfaces Infestations of CAS on cycads begin on the undersides of leaflets The leaves of infested cycads have a whitewashed appearance. Infestedof leaflets plants eventually, will typically and thehave terminal chlorotic, portion yellow-brown of the leaves,cycad. as the continuous removal of plant sap by the scale will usually Photo credit: Anne Brooke result in the death of the leaves (Weissling, 1999; Heu et al. 2003). By May 2005 it was estimated that half the king sago palms were CAS has been reported in the Taitung Cycad Nature Reserve, killed and population numbers of fadang were said to be declining Taiwan, home of the endemic prince sago the ‘Vulnerable (VU)’ (Haynes and Marler, 2005). Cycas taitungensis Besides the use of insecticides, the lady beetle, Rhyzobius lophanthae 2003, on the ‘Near Threatened (NT)’ king sago palms Cycas (Blaisdell) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae), has been used as a biological . -

Cycad Aulacaspis Scale (Aulacaspis Yasumatsui Takagi, 1977) in Mexico and Guatemala: a Threat to Native Cycads

BioInvasions Records (2017) Volume 6, Issue 3: 187–193 Open Access DOI: https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2017.6.3.02 © 2017 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2017 REABIC Rapid Communication Cycad Aulacaspis Scale (Aulacaspis yasumatsui Takagi, 1977) in Mexico and Guatemala: a threat to native cycads Benjamin B. Normark1,*, Roxanna D. Normark1, Andrew Vovides2, Lislie Solís-Montero3, Rebeca González-Gómez3, María Teresa Pulido-Silva4, Marcos Alberto Escobar-Castellanos5, Marco Dominguez5, Miguel Angel Perez-Farrera5, Milan Janda6 and Angelica Cibrian-Jaramillo7 1Department of Biology and Graduate Program in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, University of Massachusetts, 611 N Pleasant St., Amherst, MA 01003, USA 2Instituto de Ecología (INECOL), Carretera Antigua a Coatepec 351, El Haya, CP 91070 Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico 3CONACYT, El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Unidad Tapachula, Carretera Antiguo Aeropuerto km 2.5, AP 36, CP 30700 Tapachula, Chiapas, Mexico 4Laboratorio de Etnobiología Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Cd. Universitaria, Carr. Pachuca-Tulancingo, km 4.5 s/n., CP 42184 Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mexico 5Herbario Eizi Matuda, Instituto de Ciencias Biologicas, Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, Libramiento Norte Poniente 1150, Col. Lajas-Maciel, CP 29039 Tuxtla Gutierrez, Chiapas, Mexico 6Investigador Catedra CONACYT, Laboratorio Nacional de Análisis y Síntesis Ecológica (LANASE), UNAM, Morelia, Michoacan, Mexico, and Biology Centre of Czech Academy of Sciences, České Budějovice, -

<I>AULACASPIS YASUMATSUI</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: Department of Entomology Entomology, Department of 1999 AULACASPIS YASUMATSUI (HEMIPTERA: STERNORRHYNCHA: DIASPIDIDAE), A SCALE INSECT PEST OF CYCADS RECENTLY INTRODUCED INTO FLORIDA Forrest W. Howard University of Florida Avas Hamon Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services Michael Mclaughlin Fairchild Tropical Garden Thomas J. Weissling University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Si-Lin Yang University of Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologyfacpub Part of the Entomology Commons Howard, Forrest W.; Hamon, Avas; Mclaughlin, Michael; Weissling, Thomas J.; and Yang, Si-Lin, "AULACASPIS YASUMATSUI (HEMIPTERA: STERNORRHYNCHA: DIASPIDIDAE), A SCALE INSECT PEST OF CYCADS RECENTLY INTRODUCED INTO FLORIDA" (1999). Faculty Publications: Department of Entomology. 321. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologyfacpub/321 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: Department of Entomology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 14 Florida Entomologist 82(1) March, 1999 HERNÁNDEZ, L. M. 1994. Una nueva especie del género Incisitermes y dos nuevos reg- istros de termites (Isoptera) para Cuba. Avicennia 1: 87-99. LIGHT, S. F. 1930. The California species of the genus Amitermes Silvestri (Isoptera). Univ. California Publ. Entomol. 5: 173-214. LIGHT, S. F. 1932. Contribution toward a revision of the American species of Amiter- mes Silvestri. Univ. California Publ. Entomol. 5: 355-415. ROISIN, Y. 1989. The termite genus Amitermes Silvestri in Papua New Guinea. Indo- Malayan Zool. 6: 185-194. -

Non-Target Effects of Insect Biocontrol Agents and Trends in Host Specificity Since 1985

CAB Reviews 2016 11, No. 044 Non-target effects of insect biocontrol agents and trends in host specificity since 1985 Roy Van Driesche*1 and Mark Hoddle2 Address: 1 Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003-9285, USA. 2 Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA. *Correspondence: Roy Van Driesche, Email: [email protected] Received: 6 October 2016 Accepted: 7 November 2016 doi: 10.1079/PAVSNNR201611044 The electronic version of this article is the definitive one. It is located here: http://www.cabi.org/cabreviews © CAB International 2016 (Online ISSN 1749-8848) Abstract Non-target impacts of parasitoids and predaceous arthropods used for classical biological control of invasive insects include five types of impact: (1) direct attacks on native insects; (2) negative foodweb effects, such as competition for prey, apparent competition, or displacement of native species; (3) positive foodweb effects that benefited non-target species; (4) hybridization of native species with introduced natural enemies; and (5) attacks on introduced weed biocontrol agents. Examples are presented and the commonness of effects discussed. For the most recent three decades (1985–2015), analysis of literature on the host range information for 158 species of parasitoids introduced in this period showed a shift in the third decade (2005–2015) towards a preponderance of agents with an index of genus-level (60%) or species-level (8%) specificity (with only 12% being assigned a family-level or above index of specificity) compared with the first and second decades, when 50 and 40% of introductions had family level or above categorizations of specificity and only 21–27 (1985–1994 and 1995–2004, respectively) with genus or 1–11% (1985–1994 and 1995–2004, respectively) with species-level specificity. -

The Hemiptera-Sternorrhyncha (Insecta) of Hong Kong, China—An Annotated Inventory Citing Voucher Specimens and Published Records

Zootaxa 2847: 1–122 (2011) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2011 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) ZOOTAXA 2847 The Hemiptera-Sternorrhyncha (Insecta) of Hong Kong, China—an annotated inventory citing voucher specimens and published records JON H. MARTIN1 & CLIVE S.K. LAU2 1Corresponding author, Department of Entomology, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, U.K., e-mail [email protected] 2 Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department, Cheung Sha Wan Road Government Offices, 303 Cheung Sha Wan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong, e-mail [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by C. Hodgson: 17 Jan 2011; published: 29 Apr. 2011 JON H. MARTIN & CLIVE S.K. LAU The Hemiptera-Sternorrhyncha (Insecta) of Hong Kong, China—an annotated inventory citing voucher specimens and published records (Zootaxa 2847) 122 pp.; 30 cm. 29 Apr. 2011 ISBN 978-1-86977-705-0 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-706-7 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2011 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2011 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use.