University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DRUID HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT US29 Atlanta Vicinity Fulton County

DRUID HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT HABS GA-2390 US29 GA-2390 Atlanta vicinity Fulton County Georgia PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama St. NW Atlanta, GA 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY DRUID HILLS HISTORIC DISTRICT HABS No. GA-2390 Location: Situated between the City of Atlanta, Decatur, and Emory University in the northeast Atlanta metropolitan area, DeKalb County. Present Owner: Multiple ownership. Present Occupant: Multiple occupants. Present Use: Residential, Park and Recreation. Significance: Druid Hills is historically significant primarily in the areas of landscape architecture~ architecture, and conununity planning. Druid Hills is the finest examp1e of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century comprehensive suburban planning and development in the Atlanta metropo 1 i tan area, and one of the finest turn-of-the-century suburbs in the southeastern United States. Druid Hills is more specifically noted because: Cl} it is a major work by the eminent landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted and Ms successors, the Olmsted Brothers, and the only such work in Atlanta; (2) it is a good example of Frederick Law Olmsted 1 s principles and practices regarding suburban development; (3) its overall planning, as conceived by Frederick Law Olmsted and more fully developed by the Olmsted Brothers, is of exceptionally high quality when measured against the prevailing standards for turn-of-the-century suburbs; (4) its landscaping, also designed originally by Frederick Law Olmsted and developed more fully by the Olmsted Brothers, is, like its planning, of exceptionally high quality; (5) its actual development, as carried out oripinally by Joel Hurt's Kirkwood Land Company and later by Asa G. -

National Register of Historic Places Property Photograph

Form No. 10-301 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ST ' kTE Rev. 7-72 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Georgia JNTY NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES c° Fulton PROPERTY MAP FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE JUL 2 a w/i COMMON: Inman Park AND/OR HISTORIC: inman Park [H! S30iCS«^IS*IS£:::3:$:K STREET AND NUM BER: U Z) CITY OR TOWN: Atlanta STATE: CODE COUNTY: CODE i/t plillliiiiiiiilf"' " ?Georgia ••• ; 'i::-f ":;: " : "r™" : " -^^-^^-r^r^ --'•"• •«•<•"——•«"13 ••••* •:-•:•• / •• • •-•. •••• •- • • Fulton 121 |lll SOURCE: Map of Inman Park, Joel Hurt, Civil Engineer J.F. Johnson, Landscape Gardener •'"~TTl07"7~"^ UJ SCALE: 100 ff>Pt = 1 inrh y'v^-^V^T/X Hi DATE: T891 ——$ v tovED ^.i TO BE INCLUDED ON ALL MAPS 1. Property broundaries where required. 2. North arrow. -5 NATIONAL /^J 3. Latitude and longitude reference. \>£>\ REGISTER fcJ \/>x-vv: ^7 trim* " -«•• 1f "* UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Georgia COUN T Y NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Fulton PROPERTY PHOTOGRAPH FORM FOR NPS USE ON .' ENTRY NUMBER. DATE (Type all entries - attach to or enclose with photograph) JUL 2 3 1973 | 1. N >'.',£ -.: • •• . :•-.'••" jcrv,MCN: Inman Park ',-*•>. a HISTORIC: inmanPark F ICCA-nON ' ..... ' : -.';.. .•;. ; . .. u (STREET AND'NUMBER: ,_. T •/ iR TOWN: a: \ Atlanta IETATL I CODE COUNTY: ' CODE I Georgia rrrn Pnl-hnn i I?! 3. PHOTO REFERENCE -OTC CREDI T: Jet Lowe •DATE OF PHOTO: October 1970 ILi SSEGATIVC FiLEC. AT:: Georgia Historical Commission UJ oo ! CENT i F.CAT; ON DESCRlbE VlEA, DIRECTION. ETC. foj JOff 2 71973 h2 NATIONAL Beath-Dickey House, Sidewalk wall details on W\ REGlSTEh Euclid Avenue V --4^^. -

Volume I: PLAN 2040 Regional Transportation Plan (RTP)

Volume I: PLAN 2040 Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) On June 22, 2011, the Commission adopted the ARC Strategic Plan, which identifies the agency’s purpose, mission, vision, values and core principles, objectives and strategies for the future. As future plans and programs are developed, the Strategic Plan will be reflected. The contents of this report reflect the views of the persons preparing the document and those individuals are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Department of Transportation of the State of Georgia. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulations. Chapter 1 - Introduction Contents What is the Atlanta Regional Commission? ................................................................................................................... 1 What is PLAN 2040? ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 PLAN 2040’s Sustainability Focus .............................................................................................................................. 5 Meeting Federal Transportation Planning Requirements in Developing the PLAN 2040 RTP ............................ 6 Following ARC Board and Committees Guidance ....................................................................................................... 7 Stakeholder Involvement and Public -

Atlanta Streetcar System Plan

FINAL REPORT | Atlanta BeltLine/ Atlanta Streetcar System Plan This page intentionally left blank. FINAL REPORT | Atlanta BeltLine/ Atlanta Streetcar System Plan Acknowledgements The Honorable Mayor Kasim Reed Atlanta City Council Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. Staff Ceasar C. Mitchell, President Paul Morris, FASLA, PLA, President and Chief Executive Officer Carla Smith, District 1 Lisa Y. Gordon, CPA, Vice President and Chief Kwanza Hall, District 2 Operating Officer Ivory Lee Young, Jr., District 3 Nate Conable, AICP, Director of Transit and Cleta Winslow, District 4 Transportation Natalyn Mosby Archibong, District 5 Patrick Sweeney, AICP, LEED AP, PLA, Senior Project Alex Wan, District 6 Manager Transit and Transportation Howard Shook, District 7 Beth McMillan, Director of Community Engagement Yolanda Adrean, District 8 Lynnette Reid, Senior Community Planner Felicia A. Moore, District 9 James Alexander, Manager of Housing and C.T. Martin, District 10 Economic Development Keisha Lance Bottoms, District 11 City of Atlanta Staff Joyce Sheperd, District 12 Tom Weyandt, Senior Transportation Policy Advisor, Michael Julian Bond, Post 1 at Large Office of the Mayor Mary Norwood, Post 2 at Large James Shelby, Commissioner, Department of Andre Dickens, Post 3 at Large Planning & Community Development Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. Board Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director of Planning, Department of Planning & Community The Honorable Kasim Reed, Mayor, City of Atlanta Development John Somerhalder, Chairman Joshuah Mello, AICP, Assistant Director of Planning Elizabeth B. Chandler, Vice Chair – Transportation, Department of Planning & Earnestine Garey, Secretary Community Development Cynthia Briscoe Brown, Atlanta Board of Education, Invest Atlanta District 8 At Large Brian McGowan, President and Chief Executive The Honorable Emma Darnell, Fulton County Board Officer of Commissioners, District 5 Amanda Rhein, Interim Managing Director of The Honorable Andre Dickens, Atlanta City Redevelopment Councilmember, Post 3 At Large R. -

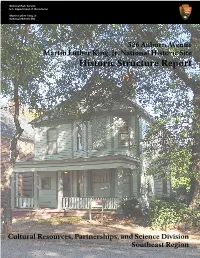

Historic Structure Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Cultural Resources, Partnerships, and Science Division Southeast Region 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report May 2017 Prepared by: WLA Studio SBC+H Architects Palmer Engineering Under the direction of National Park Service Southeast Regional Offi ce Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division The report presented here exists in two formats. A printed version is available for study at the park, the Southeastern Regional Offi ce of the National Park Service, and at a variety of other repositories. For more widespread access, this report also exists in a web-based format through ParkNet, the website of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps. gov for more information. Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division Southeast Regional Offi ce National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404)507-5847 Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 450 Auburn Avenue, NE Atlanta, GA 30312 www.nps.gov/malu About the cover: View of 526 Auburn Avenue, 2016. 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Approved By : Superintendent, Date Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Recommended By : Chief, Cultural Resource, Partnerships & Science Division Date Southeast Region Recommended By : Deputy Regional Director, -

Cip) SHORT TERM WORK PROGRAM (Stwp

CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS PROGRAM (cip) SHORT TERM WORK PROGRAM (stwp) City of Atlanta 2013-2017 Prepared by: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT MAY 2012 City of Atlanta, Georgia 2013-2017 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Short Term Work Program (STWP) Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adrean Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Aaron Watson H. Lamar Willis Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Project Staff Department of Planning and Community Development James E. Shelby, Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Garnett Brown, Assistant Director Capital Improvements Program Sub-Cabinet Atlanta BeltLine, Inc Invest Atlanta Office of Sustainability Rukiya Eaddy Granvel Tate Aaron Bastian Lee Harrop Flor Velarde Atlanta Housing Office of Enterprise Assets Parks, Recreation and Authority Management Cultural Affairs Trish O’Connell Shannon Burton Alvin Dodson Glen Cowart Daryl Mosley Aviation William Hunt Paul Taylor Shelley Lamar Valerie Oyakhire Office of Housing Police Derrick Jordan Tony Distephano Corrections Department Rodney Milton Darlene Jackson-Williams Yolanda Paschall December Thompson Reginald Mitchell Rodney Stinson Michael Richardson Office of Human Services Tracy Woodard Finance Arthur Cole Charlotte Daniely Public Works Lee Hannah Office of Planning Douglas Raikes Carol King Enrique Bascunana Michele Wynn Antrameka Knight Shawn Brown Karen Sutton Randy G. -

March 2021 Volume 36 | Number 1

March 2021 Volume 36 | Number 1 CONTENTS Sidewalk Letter to DeKalb CEO 4 Olmsted 200 Celebration Update 6 2021 Plein Air Invitational 10 DHCA Membership Thank You 26 - 27 Home Means Everything. The resiliency of Atlanta this year has been astounding. The meaning of home continues to evolve and my appreciation for matching families with their dream home has deepened. From Decatur to Druid Hills to Lake Claire, every home is special. Let me help you find your place in the world! —Natalie NATALIE GREGORY 404.373.0076 | 404.668.6621 [email protected] nataliegregory.com | nataliegregoryandco 401 Mimosa Drive 369 Mimosa Drive ACTIVE | Decatur ACTIVE | Decatur $1,225,000 | 6 BD | 5 BA $1,175,000 | 5 BD | 4.5 BA 3 Lullwater Estate NE 973 Clifton Road 330 Ponce De Leon Place ACTIVE | Druid Hills ACTIVE | Druid Hills UNDER CONTRACT | Decatur $799,000 | 2 BD | 2.5 BA $725,000 | 3 BD | 2 BA $1,025,000 | 5 BD | 3 BA Compass is a licensed real estate broker and abides by Equal Housing Opportunity laws. All material presented herein is intended for informational purposes only. Information is compiled from sources deemed reliable but is subject to errors, omissions, changes in price, condition, sale, or withdrawal without notice. No statement is made as to the accuracy of any description. All measurements and square footages are approximate. This is not intended to solicit property already listed. Nothing herein shall be construed as legal, accounting or other professional advice outside the realm of real estate brokerage. March 2021 THE DRUID HILLS NEWS 3 President’s Corner Druid Hills Civic Association By Kit Eisterhold President: Communications Vice President: Kit Eisterhold Open ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Dear Neighbors, Hard to know what difference it will make, neces- First Vice President: Treasurer: sarily, one guy writing a letter. -

Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area Geologic

GeologicGeologic Resource Resourcess Inventory Inventory Scoping Scoping Summary Summary Chattahoochee Glacier Bay National River NationalPark, Alaska Recreation Area Georgia Geologic Resources Division PreparedNational Park by Katie Service KellerLynn Geologic Resources Division October US Department 31, 2012 of the Interior National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior The Geologic Resources Inventory (GRI) Program, administered by the Geologic Resources Division (GRD), provides each of 270 identified natural area National Park System units with a geologic scoping meeting, a scoping summary (this document), a digital geologic map, and a geologic resources inventory report. Geologic scoping meetings generate an evaluation of the adequacy of existing geologic maps for resource management. Scoping meetings also provide an opportunity to discuss park-specific geologic management issues, distinctive geologic features and processes, and potential monitoring and research needs. If possible, scoping meetings include a site visit with local experts. The Geologic Resources Division held a GRI scoping meeting for Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area on March 19, 2012, at the headquarters building in Sandy Springs, Georgia. Participants at the meeting included NPS staff from the national recreation area, Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, and the Geologic Resources Division; and cooperators from the University of West Georgia, Georgia Environmental Protection Division, and Colorado State University (see table 2, p. 21). During the scoping meeting, Georgia Hybels (NPS Geologic Resources Division, GIS specialist) facilitated the group’s assessment of map coverage and needs, and Bruce Heise (NPS Geologic Resources Division, GRI program coordinator) led the discussion of geologic features, processes, and issues. Jim Kennedy (Georgia Environmental Protection Division, state geologist) provided a geologic overview of Georgia, with specific information about the Chattahoochee River area. -

HISTORIC DISTRICT INFORMATION FORM (HDIF) Revised June 2015

HISTORIC DISTRICT INFORMATION FORM (HDIF) Revised June 2015 INSTRUCTIONS: Use this form for a National Register nomination for a district such as a residential neighborhood, downtown commercial area, or an entire city. If you are nominating an individual building or a small complex of buildings such as a farm or a school campus, use the Historic Property Information Form (HPIF). The information called for by this form is required for a National Register nomination and is based on the National Park Service’s National Register Bulletin: How to Complete the National Register Registration Form. Therefore, the information must be provided to support a request for a National Register nomination. You may use this form on your computer and insert information at the appropriate places. This form is available online at www.georgiashpo.org, or by e-mail from the Historic Preservation Division (HPD). Submit the information on a CD or DVD in Word format (not pdf) and send a hard copy. Make sure you include all requested information. This will greatly expedite the processing of your nomination and avoid HPD from having to ask for it. Information requested in this HDIF is necessary to document the district to National Register standards and will be incorporated into the final National Register form prepared by HPD’s staff. If you wish to use the official National Register nomination form instead of this form, please contact the National Register Program Manager at the Historic Preservation Division for direction; be advised that if you use the official National Register form, you must include all of the information and support documentation called for on this HDIF and submit Section 1 of the HDIF. -

Druid Hills Olmsted Documentary Record

DRUID HILLS OLMSTED DOCUMENTARY RECORD SELECTED TEXTS CORRESPONDENCE Between the Olmsted Firm and Kirkwood Land Company From the Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted And the Records of the Olmsted Firm In the Manuscript Division Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. And The Olmsted National Historic Site Brookline, Massachusetts Compiled by Charles E. Beveridge, Series Editor The Frederick Law Olmsted Papers With a List of Correspondence Compiled by Sarah H. Harbaugh 1 CONTENTS by Topic Additions of land, proposed Olmsted Firm Atkins Park development Olmsted, Frederick Law Beacon Street, Boston Olmsted, John C Bell Street, Extension of Parkway to Atlanta Biltmore nursery Plans Boundary revisions Planting Business district, proposed Plant materials Casino Ponce de Leon Parkway Clifton Pike, Crossing of Parkway Presbyterian University Construction Public reservations Druid Hills plan Residential Lots Druid Hills site Restrictions, in deeds Eastern section Ruff, Solon Z. Electric power lines Sale agreement Electric railway Section 1 Entrance Sewerage system GC&N RR Southern section Grading Southwestern section Hurt, Joel Springdale Kirkwood Land Company Stormwater drainage Lakes Street railway Land values Street tree planting Lullwater Streets Names Water supply system Nursery Widewater APPENDIX: LIST OF CORRESPONDENCE: Correspondence 1890 – 1910 Followed by selected photographs, map and drawing 2 ADDITIONS OF LAND, PROPOSED The Library of Congress, Manuscript Division Olmsted Associates Papers, vol. A11, p. 250 5th December 1890 6. When on the ground with your Secretary, we pointed out certain lands lying outside of that which you now have, the addition of which would, we think, for reasons explained to him and to you, greatly add to the ultimate value of the property. -

TRANSFORMATION PLAN UNIVERSITY AREA U.S.Department of Housing and Urban Development ATLANTA HOUSING AUTHORITY

Choice Neighborhoods Initiative TRANSFORMATION PLAN UNIVERSITY AREA U.S.Department of Housing and Urban Development ATLANTA HOUSING AUTHORITY ATLANTA, GEORGIA 09.29.13 Letter from the Interim President and Chief Executive Officer Acknowledgements Atlanta Housing Authority Board of Commissioners Atlanta University Center Consortium Schools Daniel Halpern, Chair Clark Atlanta University Justine Boyd, Vice-Chair Dr. Carlton E. Brown, President Cecil Phillips Margaret Paulyne Morgan White Morehouse College James Allen, Jr. Dr. John S. Wilson, Jr., President Loretta Young Walker Morehouse School of Medicine Dr. John E. Maupin, Jr., President Atlanta Housing Authority Choice Neighborhoods Team Spelman College Joy W. Fitzgerald, Interim President & Chief Executive Dr. Beverly Tatum, President Officer Trish O’Connell, Vice President – Real Estate Development Atlanta University Center Consortium, Inc. Mike Wilson, Interim Vice President – Real Estate Dr. Sherry Turner, Executive Director & Chief Executive Investments Officer Shean L. Atkins, Vice President – Community Relations Ronald M. Natson, Financial Analysis Director, City of Atlanta Kathleen Miller, Executive Assistant The Honorable Mayor Kasim Reed Melinda Eubank, Sr. Administrative Assistant Duriya Farooqui, Chief Operating Officer Raquel Davis, Administrative Assistant Charles Forde, Financial Analyst Atlanta City Council Adrienne Walker, Grant Writer Councilmember Ivory Lee Young, Jr., Council District 3 Debra Stephens, Sr. Project Manager Councilmember Cleta Winslow, Council District -

Before Olmsted – the New South Career of Joseph Forsyth Johnson

THOMASW. HANCHETT Before Olmsted Tfie IVea Soath Career of Joseph Forsyth Johnson THe wonx revolution in city planning took place in the second half oF BRITISH of the nineteenth century. America's long tradition of LANDSCAPE straight streets and rectangular blocks began to give way DESIGNER A to a new urban landscape of gracefully avenues JOH NSON curving STARTED THE nd tree-shaded parks. The trend began in England SoUTH,S SHIFT where landscape architects had worked out the principles of "naturalis- AWAY FROM THE tic planning" on the countrv estates of the u,ealthy. Frederick Law MONOTONOUS Olmsted, the landscape architect famous for creating New York City's URBAN STREET Central Park and Atlanta's Druid Hills THE npvor-i-Tlo\ in urban planning that GRID. suburb, often gets credit for the gro*'th began in the late nineteenth century came of natural planning in the L. nited Stares. as part of a broad new approach to aesthet- But he was not alone. ics that originated in England and spread In the American South, a British-born throughout the western world. Its most designer named Joseph Forsyth Johnson eloquent advocate was the British art critic played a pivotal role in introducing the John Ruskin, who, in a series of volumes notion of naturalistic planning. Johnson published during the 1840s and 1850s, came to Atlanta in 1887, several years issued a stirring call for an end to the' before Olmsted, bringing English land- formal geometries of the Renaissance. scape ideas with him. It was Johnson who Instead of using straight lines and rigid designed Atlanta's first naturalistic suburb, symmetries, he argued, artists and archi- Inman Park, and began the creation of tects should emulate the subtlety and the urban glade now known as Piedmont informality of nature.