HISTORIC DISTRICT INFORMATION FORM (HDIF) Revised June 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home Sellers in Buckhead and Intown Atlanta Neighborhoods Reap

Vol. 4, Issue 2 | 1st Quarter 2011 BEACHAM Your Monthly Market Update From 3284 Northside Parkway The Best People in Atlanta Real Estate™ Suite 100 Atlanta, GA 30327 404.261.6300 Insider www.beacham.com Home sellers in Buckhead and Intown Atlanta What’s neighborhoods reap the benefits of an early spring Hot The luxury market. There he spring selling season came early for many intown real estate markets like Buckhead and the were 13 sales homes in metro Atlanta priced neighborhoods in Buckhead and what is rest of the Atlanta are varied according to Carver. $2 million or more in considered “In-town Atlanta” (Ansley Park, East First and foremost, Buckhead is a top housing draw T the first quarter (11 in Buckhead, Midtown, Morningside, Virginia-Highlands), in any market because of its proximity to the city’s Buckhead, 2 in East Cobb), where single family home sales collectively rose 21% greatest concentration of exceptional homes, high a 63% increase from from the first quarter of 2010 and prices increased 6%. paying jobs, shopping, restaurants, schools, etc. the first quarter a year The story was not as rosy for the rest In March, more than With an average home sale price ago. However, sales are of metro Atlanta, however. While single of $809,275 in the first quarter, still 32% below the first family home sales were up 5% in the first 15% of our new listings Buckhead is an affluent community quarter of 2007 when the quarter, prices were down 8% from a year went under contract and the affluent have emerged luxury market was peaking. -

Economic Cluster Review Metro Atlanta

ECONOMIC CLUSTER REVIEW METRO ATLANTA Submitted by Market Street Services Inc. www.marketstreetservices.com June 19, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Overview ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Scope of Work ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Facilitators ................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Economic Development Targeting 101 .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Economic Cluster Review ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Developing a Cohesive Message ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Research Methods ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Metro Atlanta: A Global Commerce Hub ...................................................................................................................... -

THE Inman Park

THE Inman Park Advocator Atlanta’s Small Town Downtown News • Newsletter of the Inman Park Neighborhood Association November 2015 [email protected] • inmanpark.org • 245 North Highland Avenue NE • Suite 230-401 • Atlanta 30307 Volume 43 • Issue 11 Coming Soon BY DENNIS MOBLEY • [email protected] Inman Park Holiday Party I’m pr obably showing my Friday,2015 December 11 • 7:30 pm – 11:00 pm age, but I can remember the phrase “coming soon to a The Trolley Barn • 963 Edgewood Avenue theater near you” like it was yesterday. In this case, I The annual Inman Park Holiday Party returns wanted to give our readers a heads-up as to what they can to The Trolley Barn this year. Don’t miss this expect with our conversion to chance to meet and visit with fellow Inman President’s Message the MemberClicks-powered Park neighborsHoliday over food, drinks Party and dancing. IPNA website and associated membership management software. Enjoy heavy hors d’oeuvres catered by Stone By the time you read this November issue of the Advocator, some Soup and complimentaryAnnouncement beer and wine. A 400+ of you will have received an email from our Vice President DJ will be there to spin a delightful mix of old of Communications, James McManus, notifying you that you standards and newMissing favorites. So don your are believed to be a current IPNA member in good standing. (We holiday fi nest and join us for a good time! gleaned this list of 400+ from our current database and believe it to be fairly accurate). -

Case Studies of Accounting Concepts and Principles

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 5-9-2020 Case Studies of Accounting Concepts and Principles Jones Albritton Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Accounting Commons Recommended Citation Albritton, Jones, "Case Studies of Accounting Concepts and Principles" (2020). Honors Theses. 1421. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1421 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Case Studies of Accounting Concepts and Principles By Sam Jones Albritton IV A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2020 Approved by Advisor: Dr. Victoria Dickinson Reader: Dr. W. Mark Wilder i ABSTRACT SAM JONES ALBRITTON IV: Case Studies of Accounting Concepts and Principles (Under the Direction of Victoria Dickinson) The following thesis contains solutions to case studies performed on various accounting standards in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, GAAP. Each case study focuses on a different area of financial reporting with some focusing on the principles and others on the documentation. The case studies were done in conjunction with topics learned during the Intermediate Financial Accounting class. The thesis shows understanding of accounting and financial reporting principles as well as current accounting topics in accordance with GAAP. The case studies were performed under the guidance of Victoria Dickenson and the Patterson School of Accounting in the Accy 420 course during the 2018 to 2019 school year. -

The Impact of the Hospitality & Tourism Industry on Atlanta

The Impact of the Hospitality & Tourism Industry on Atlanta Debby Cannon, Ph.D. Director Cecil B. Day School of Hospitality Robinson College of Business Georgia State University Hospitality Hospitality& & TourismTourism in Atlanta Recreation, Travel Conventions, Attractions, Air, Rail, Lodging/ Meetings, Restaurants/ Sporting Hotels/ Auto, Tradeshows, Foodservice Events, Resorts Coach Events Parks Tourism in Georgia • 48 million visitors annually who spend over $25 billion • Supports $6 billion in resident wages and over 400,000 jobs • 8th largest tourism economy in the country • Over $708.5 million in state tax revenue from visitor expenditures • Equates to a $380 savings on state and local taxes per household. Tourism in Atlanta • Accounts for 51% of Georgia’s tourism economy • 35+ million visit Atlanta annually • More than $11 billion is generated in visitor spending; $29 million per day (direct spending) • Sustains over 238,000 jobs • In Atlanta, “Leisure & Hospitality” employs 9.3% of the metro workers Atlanta’s Lodging Market Atlanta – 3rd in the nation in hotel rooms #1 - Las Vegas (133,186 rooms) #2 - Orlando (112,156 rooms) #3 - Atlanta (92,000 rooms) • 15,000 hotel rooms in downtown Atlanta • 92,000 rooms in Metro Atlanta • Within next three years, eleven new hotels will add over 2,000 new rooms •Over $210 million is currently being spent on upgrades and renovations of Atlanta’s hotels Atlanta Market June 2007 Room Supply Share Alpharetta 4% Perimeter 5% West 5% Northwest 6% Northeast 7% East 8% Chamblee 9% South 9% Buckhead -

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP)

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP) Prepared By: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT JUNE 2015 Page is left blank intentionally for document formatting City of Atlanta 2016‐2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) and Community Work Program (CWP) June 2015 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Office of Planning 55 Trinity Avenue Suite 3350 Atlanta, GA 30303 http://www.atlantaga.gov/indeex.aspx?page=391 Online City Projects Database: http:gis.atlantaga.gov/apps/cityprojects/ Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adreaan Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Mary Norwood Andre Dickens Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development Terri M. Lee, Deputy Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Project Staff Jessica Lavandier, Assistant Director, Strategic Planning Rodney Milton, Principal Planner Lenise Lyons, Urban Planner Capital Improvements Program Sub‐Cabinet Members Atlanta BeltLine, -

Volume I: PLAN 2040 Regional Transportation Plan (RTP)

Volume I: PLAN 2040 Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) On June 22, 2011, the Commission adopted the ARC Strategic Plan, which identifies the agency’s purpose, mission, vision, values and core principles, objectives and strategies for the future. As future plans and programs are developed, the Strategic Plan will be reflected. The contents of this report reflect the views of the persons preparing the document and those individuals are responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Department of Transportation of the State of Georgia. This report does not constitute a standard, specification, or regulations. Chapter 1 - Introduction Contents What is the Atlanta Regional Commission? ................................................................................................................... 1 What is PLAN 2040? ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 PLAN 2040’s Sustainability Focus .............................................................................................................................. 5 Meeting Federal Transportation Planning Requirements in Developing the PLAN 2040 RTP ............................ 6 Following ARC Board and Committees Guidance ....................................................................................................... 7 Stakeholder Involvement and Public -

Atlanta Streetcar System Plan

FINAL REPORT | Atlanta BeltLine/ Atlanta Streetcar System Plan This page intentionally left blank. FINAL REPORT | Atlanta BeltLine/ Atlanta Streetcar System Plan Acknowledgements The Honorable Mayor Kasim Reed Atlanta City Council Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. Staff Ceasar C. Mitchell, President Paul Morris, FASLA, PLA, President and Chief Executive Officer Carla Smith, District 1 Lisa Y. Gordon, CPA, Vice President and Chief Kwanza Hall, District 2 Operating Officer Ivory Lee Young, Jr., District 3 Nate Conable, AICP, Director of Transit and Cleta Winslow, District 4 Transportation Natalyn Mosby Archibong, District 5 Patrick Sweeney, AICP, LEED AP, PLA, Senior Project Alex Wan, District 6 Manager Transit and Transportation Howard Shook, District 7 Beth McMillan, Director of Community Engagement Yolanda Adrean, District 8 Lynnette Reid, Senior Community Planner Felicia A. Moore, District 9 James Alexander, Manager of Housing and C.T. Martin, District 10 Economic Development Keisha Lance Bottoms, District 11 City of Atlanta Staff Joyce Sheperd, District 12 Tom Weyandt, Senior Transportation Policy Advisor, Michael Julian Bond, Post 1 at Large Office of the Mayor Mary Norwood, Post 2 at Large James Shelby, Commissioner, Department of Andre Dickens, Post 3 at Large Planning & Community Development Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. Board Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director of Planning, Department of Planning & Community The Honorable Kasim Reed, Mayor, City of Atlanta Development John Somerhalder, Chairman Joshuah Mello, AICP, Assistant Director of Planning Elizabeth B. Chandler, Vice Chair – Transportation, Department of Planning & Earnestine Garey, Secretary Community Development Cynthia Briscoe Brown, Atlanta Board of Education, Invest Atlanta District 8 At Large Brian McGowan, President and Chief Executive The Honorable Emma Darnell, Fulton County Board Officer of Commissioners, District 5 Amanda Rhein, Interim Managing Director of The Honorable Andre Dickens, Atlanta City Redevelopment Councilmember, Post 3 At Large R. -

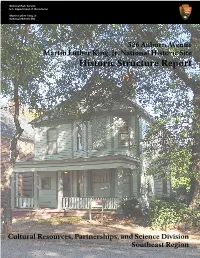

Historic Structure Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Cultural Resources, Partnerships, and Science Division Southeast Region 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report May 2017 Prepared by: WLA Studio SBC+H Architects Palmer Engineering Under the direction of National Park Service Southeast Regional Offi ce Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division The report presented here exists in two formats. A printed version is available for study at the park, the Southeastern Regional Offi ce of the National Park Service, and at a variety of other repositories. For more widespread access, this report also exists in a web-based format through ParkNet, the website of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps. gov for more information. Cultural Resources, Partnerships, & Science Division Southeast Regional Offi ce National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404)507-5847 Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site 450 Auburn Avenue, NE Atlanta, GA 30312 www.nps.gov/malu About the cover: View of 526 Auburn Avenue, 2016. 526 Auburn Avenue Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Historic Structure Report Approved By : Superintendent, Date Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Recommended By : Chief, Cultural Resource, Partnerships & Science Division Date Southeast Region Recommended By : Deputy Regional Director, -

Urban New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q20

Altanta - Urban New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 1Q20 ID PROPERTY UNITS 1 Generation Atlanta 336 60 145 62 6 Elan Madison Yards 495 142 153 58 9 Skylark 319 14 70 10 Ashley Scholars Landing 135 59 14 NOVEL O4W 233 148 154 110 17 Adair Court 91 65 Total Lease Up 1,609 1 144 21 Ascent Peachtree 345 26 Castleberry Park 130 27 Link Grant Park 246 21 35 Modera Reynoldstown 320 111 University Commons 239 127 39 915 Glenwood 201 Total Planned 6,939 64 68 Total Under Construction 1,242 111 126 66 100 26 109 205 116 Abbington Englewood 80 155 50 Milton Avenue 320 129 99 120 Hill Street 280 124 103 53 Broadstone Summerhill 276 124 222 Mitchell Street 205 67 101 54 Georgia Avenue 156 134 Mixed-Use Development 100 125 240 Grant Street 297 10 125 58 Centennial Olympic Park Drive 336 126 41 Marietta St 131 59 Courtland Street Apartment Tower 280 127 Luckie Street 100 35 137 104 60 Spring Street 320 128 Modera Beltline 400 6 62 Ponce De Leon Avenue 129 Norfolk Southern Complex Redevelopment 246 Mixed-Use Development 135 130 72 Milton Apartments - Peoplestown 383 64 220 John Wesley Dobbs Avenue NE 321 53 27 65 Angier Avenue 240 131 Hank Aaron Drive 95 66 Auburn 94 132 Summerhill 965 39 67 McAuley Park Mixed-Use 280 133 Summerhill Phase II 521 98 54 132 68 StudioPlex Hotel 56 134 930 Mauldin Street 143 133 70 North Highland 71 137 Memorial Drive Residential Development 205 142 Quarry Yards 850 96 Chosewood Park 250 105 17 98 565 Hank Aaron Drive 306 144 Atlanta First United Methodist 100 99 Avery, The 130 145 Echo Street 650 100 Downtown -

Cip) SHORT TERM WORK PROGRAM (Stwp

CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS PROGRAM (cip) SHORT TERM WORK PROGRAM (stwp) City of Atlanta 2013-2017 Prepared by: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT MAY 2012 City of Atlanta, Georgia 2013-2017 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Short Term Work Program (STWP) Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adrean Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Aaron Watson H. Lamar Willis Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Project Staff Department of Planning and Community Development James E. Shelby, Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Garnett Brown, Assistant Director Capital Improvements Program Sub-Cabinet Atlanta BeltLine, Inc Invest Atlanta Office of Sustainability Rukiya Eaddy Granvel Tate Aaron Bastian Lee Harrop Flor Velarde Atlanta Housing Office of Enterprise Assets Parks, Recreation and Authority Management Cultural Affairs Trish O’Connell Shannon Burton Alvin Dodson Glen Cowart Daryl Mosley Aviation William Hunt Paul Taylor Shelley Lamar Valerie Oyakhire Office of Housing Police Derrick Jordan Tony Distephano Corrections Department Rodney Milton Darlene Jackson-Williams Yolanda Paschall December Thompson Reginald Mitchell Rodney Stinson Michael Richardson Office of Human Services Tracy Woodard Finance Arthur Cole Charlotte Daniely Public Works Lee Hannah Office of Planning Douglas Raikes Carol King Enrique Bascunana Michele Wynn Antrameka Knight Shawn Brown Karen Sutton Randy G. -

Imagine Memorial

A PARTNERSHIP BETWEEN HON. N ATA LY N ARCHIBONG AND THE GEORGIA TECH SCHOOL OF CITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING • Edgewood • Kirkwood • Grant Park • Glenwood Park • Cabbagetown • East Lake • Oakhurst • Reynoldstown • East Atlanta • What We Will Talk About • Imagine Memorial as the Spine of a Diverse Urban Experience • Outreach – the Foundation of Our Efforts • Land Use and Development • Transportation • Connectivity • Implementation • Next Steps: Livable Centers Initiative • Edgewood • Kirkwood • Grant Park • Glenwood Park • Cabbagetown • East Lake • Oakhurst • Reynoldstown • East Atlanta • Outreach Goals and Outcomes: ◦ Listening ◦ Incorporating: ◦ Existing plans ◦ Development initiatives ◦ Citizen and stakeholder priorities ◦ Launching community-guided implementation strategy • Edgewood • Kirkwood • Grant Park • Glenwood Park • Cabbagetown • East Lake • Oakhurst • Reynoldstown • East Atlanta • • Edgewood • Kirkwood • Grant Park • Glenwood Park • Cabbagetown • East Lake • Oakhurst • Reynoldstown • East Atlanta • Outreach Action Plan • Attended September and October meetings of many neighborhood associations and five NPUs • Encouraged residents to offer feedback, which was foundation of plan • Reached out to many public and private sector institutional stakeholders, such as City of Atlanta, GDOT, MARTA, and several developers • Solicited feedback from community leaders in early Residents writing suggestions on a map at a Reynoldstown Civic Improvement League meeting September • Edgewood • Kirkwood • Grant Park • Glenwood Park • Cabbagetown •