Peter Charles Sturman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ists As All Embellishments Fade, Freshness Fills the Universe

Xu Wei and European Missionaries: As All Embellishments Fade, Freshness Fills Early Contact between Chinese Artists the Universe - The Formation and Development and the West of Freehand Flower-and-Bird Ink Paintings of Chen Chun and Xu Wei Chen Ruilin 陳瑞林 Chen Xiejun 陳燮君 Professor Director and Researcher Academy of Fine Arts, Tsinghua University Shanghai Museum The period encompassing the late Ming and early Qing Dynasty in the 16th and 17th centuries was an era When considering the development of flower-and-bird paintings in the Ming Dynasty, the most remark- of momentous change in Chinese society. It was also an era of great change in Chinese painting. Literati art- able is the achievements of freehand flower ink paintings. Of all artists, Chen Chun and Xu Wei have been ists gathered under the banners of a multitude of different Schools, and masterful artists appeared one after the most groundbreaking and inspirational, to the extent that they are known as “Qing Teng and Bai Yang” another, producing a multitude of works to greatly advance the development of Chinese painting. As literati in the history of Chinese painting. Chen Chun, a foremost example of the “Wu Men” painting school, sought art developed, however, Western art was encroaching upon China and influencing Chinese painting. The suc- inspiration in landscapes and flowers. In particular, he inherited the tradition of flower-and-bird ink painting cession of European missionaries that came to China brought Western painting with them and, actively inter- established by Shen Zhou and other preceding masters. Through a combination of uninhibited brushwork acting with China’s scholar-officials in the course of their missionary activities, introduced Western painting and ink he established a new mode in his own right, which emphasized vigour and free style. -

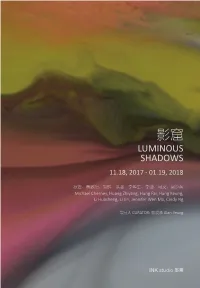

影窟 Luminous Shadows 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018

影窟 LUMINOUS SHADOWS 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018 秋麦、黄致阳、熊辉、洪强、李华生、李津、马文、吴少英 Michael Cherney, Huang Zhiyang, Hung Fai, Hung Keung, Li Huasheng, Li Jin, Jennifer Wen Ma, Cindy Ng 策展人 CURATOR: 杨浚承 Alan Yeung 影窟 LUMINOUS SHADOWS 11.18, 2017 - 01.19, 2018 秋麦、黄致阳、熊辉、洪强、李华生、李津、马文、吴少英 Michael Cherney, Huang Zhiyang, Hung Fai, Hung Keung, Li Huasheng, Li Jin, Jennifer Wen Ma, Cindy Ng 策展人 CURATOR: 杨浚承 Alan Yeung Contents 006 展览介绍 Introduction 006 杨浚承 Alan Yeung 006 作品 Works 010 006 秋麦 Michael Cherney 010 黄致阳 Huang Zhiyang 026 熊辉 Hung Fai 050 洪强 Hung Keung 076 李华生 Li Huasheng 084 李津 Li Jin 112 马文 Jennifer Wen Ma 150 吴少英 Cindy Ng 158 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Ink Studio. © 2017 Ink Studio Artworks © 1981-2017 The Artists (Front Cover Image 封面图片 ) 吴少英 Cindy NG | Sea of Flowers 花海 (detail 局部 ) | P116 (Back Cover Image 封底图片 ) 李津 Li Jin | The Hungry Tigress 舍身饲虎 (detail 局部 ) | P162 6 7 INTRODUCTION Alan Yeung A painted rock bleeds as living flesh across sheets of paper. A quivering line In Jennifer Wen Ma’s (b. 1970, Beijing) installation, light and glass repeatedly gives form to the nuances of meditative experience. The veiled light of an coalesce into an illusionary landscape before dissolving in a reflective ink icon radiates through the near-instantaneous marks by a pilgrim’s hand. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian

Macalester International Volume 18 Chinese Worlds: Multiple Temporalities Article 12 and Transformations Spring 2007 Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian Desheng Fang Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl Recommended Citation Qian, Zhuzhong and Fang, Desheng (2007) "Towards Chinese Calligraphy," Macalester International: Vol. 18, Article 12. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol18/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Global Citizenship at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester International by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards Chinese Calligraphy Qian Zhuzhong and Fang Desheng I. History of Chinese Calligraphy: A Brief Overview Chinese calligraphy, like script itself, began with hieroglyphs and, over time, has developed various styles and schools, constituting an important part of the national cultural heritage. Chinese scripts are generally divided into five categories: Seal script, Clerical (or Official) script, Regular script, Running script, and Cursive script. What follows is a brief introduction of the evolution of Chinese calligraphy. A. From Prehistory to Xia Dynasty (ca. 16 century B.C.) The art of calligraphy began with the creation of Chinese characters. Without modern technology in ancient times, “Sound couldn’t travel to another place and couldn’t remain, so writings came into being to act as the track of meaning and sound.”1 However, instead of characters, the first calligraphy works were picture-like symbols. These symbols first appeared on ceramic vessels and only showed ambiguous con- cepts without clear meanings. -

Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras YEN-WEN CHENG University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, and the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation CHENG, YEN-WEN, "Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 98. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras Abstract After obtaining sovereignty, a new emperor of China often gathers the imperial collections of previous dynasties and uses them as evidence of the legitimacy of the new regime. Some emperors go further, commissioning the compilation projects of bibliographies of books and catalogues of artistic works in their imperial collections not only as inventories but also for proclaiming their imperial power. The imperial collections of art symbolize political and cultural predominance, present contemporary attitudes toward art and connoisseurship, and reflect emperors’ personal taste for art. The attempt of this research project is to explore the practice of art cataloguing during two of the most important reign periods in imperial China: Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (r. 1101-1125) and Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (r. 1736-1795). Through examining the format and content of the selected painting, calligraphy, and bronze catalogues compiled by both emperors, features of each catalogue reveal the development of cataloguing imperial artistic collections. -

Zhang Dai's Biographical Portraits

Mortal Ancestors, Immortal Images: Zhang Dai’s Biographical Portraits Duncan M. Campbell, Australian National University Nobody looking at paintings and who sees a picture of the Three Sovereigns and the Five Emperors fails to be moved to respect and veneration, or, on the other hand, to sadness and regret when seeing pictures of the last rulers of the Three Dynasties. Looking at traitorous ministers or rebel leaders sets one’s teeth grinding whereas, on sight of men of integrity or of great wisdom, one forgets to eat, on sight of loyal ministers dying for their cause one is moved to defend one’s own integrity … From this consideration does one understand that it is illustrations and paintings that serve to hold up a mirror to our past in order to provide warnings for our future course of action. (觀畫者見三皇五帝莫不仰戴見三季異主莫不悲惋見篡臣賊嗣莫不切齒見高節 妙士莫不忘食見忠臣死難莫不抗節…是知存乎鑒戒者圖畫也) Cao Zhi 曹植 (192–232), quoted in Zhang Yanyuan 張彥遠 (9th Century), Lidai minghua ji 歷代名畫記 [A Record of Famous Paintings Down Through the Ages] In keeping with the name it took for itself (ming 明, brilliant, luminous, illustrious), the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) was a moment of extraordinary development in the visual cultures of the traditional Chinese world (Clunas 1997; 2007).1 On the one hand, this period of Chinese history saw internal developments in various aspects of preexisting visual culture; on the other, through developments in xylography and commercial publishing in particular, but also through the commoditization of the objects of culture generally, the period also saw a rapid increase in the dissemination and circulation of 1 Clunas writes: ‘The visual is central in Ming life; this is true whether it is the moral lecturer Feng Congwu (1556–?1627) using in his impassioned discourses a chart showing a fork in the road, one path leading to good and one path to evil, or in the importance in elite life of dreams as “visions,” one might say as “visual culture,” since they made visible, to the dreamer at least, cultural assumptions about fame and success’ (2007: 13). -

Downloaded 4.0 License

86 Chapter 3 Chapter 3 Eloquent Stones Of the critical discourses that this book has examined, one feature is that works of art are readily compared to natural forms of beauty: bird song, a gush- ing river or reflections in water are such examples. Underlying such rhetorical devices is an ideal of art as non-art, namely that the work of art should appear so artless that it seems to have been made by nature in its spontaneous process of creation. Nature serves as the archetype (das Vorbild) of art. At the same time, the Song Dynasty also saw refined objects – such as flowers, tea or rocks – increasingly aestheticised, collected, classified, described, ranked and com- moditised. Works of connoisseurship on art or natural objects prospered alike. The hundred-some pu 譜 or lu 錄 works listed in the literature catalogue in the History of the Song (“Yiwenzhi” in Songshi 宋史 · 藝文志) are evenly divided between those on manmade and those on natural objects.1 Through such dis- cursive transformation, ‘natural beauty’ as a cultural construct curiously be- came the afterimage (das Nachbild) of art.2 In other words, when nature appears as the ideal of art, at the same time it discovers itself to be reshaped according to the image of art. As a case study of Song nature aesthetics, this chapter explores the multiple dimensions of meaning invested in Su Shi’s connoisseur discourse on rocks. Su Shi professed to be a rock lover. Throughout his life, he collected inkstones, garden rocks and simple pebbles. We are told, for instance, that a pair of rocks, called Qiuchi 仇池, accompanied him through his exiles to remote Huizhou and Hainan, even though most of his family members were left behind. -

Analysis on the Translation of Mao Zedong's 2Nd Poem in “送瘟神 'Sòng Wēn Shén'” by Arthur Cooper in the Light O

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 11, No. 8, pp. 910-916, August 2021 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1108.06 Analysis on the Translation of Mao Zedong’s 2nd Poem in “送瘟神 ‘sòng wēn shén’” by Arthur Cooper in the Light of “Three Beauties” Theory Pingli Lei Guangdong Baiyun University, Guangzhou 510450, Guangdong, China Yi Liu Guangdong Baiyun University, Guangzhou 510450, Guangdong, China Abstract—Based on “Three Beauties” theory of Xu Yuanchong, this paper conducts an analysis on Arthur Cooper’s translation of “送瘟神”(2nd poem) from three aspects: the beauty of sense, sound and form, finding that, because of his lack of empathy for the original poem, Cooper fails to convey the connotation of the original poem, the rhythm and the form of the translated poem do not match Chinese classical poetry, with three beauties having not been achieved. Thus, the author proposes that, in order to better spread the culture of Chinese classical poetry and convey China’s core spirit to the world, China should focus on cultivating the domestic talents who have a deep understanding about Chinese culture, who are proficient not only in Chinese classical poetry, but also in classical poetry translation. Index Terms—“Three Beauties” theory, “Song When Shen(2nd poem)” , Arthur Cooper, English translation of Chinese classical poetry I. INTRODUCTION China has a long history in poetry creation, however, the research on poetry translation started very late in China Even in the Tang and Song Dynasties, when poetry writing was popular and when culture was open, there did not appear any relevant translation researches. -

Nations and Art: the Shaping of Art in Communist Regimes

NATIONS AND ART: THE SHAPING OF ART IN COMMUNIST REGIMES Lena Galperina Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson Fall 09 and Spring 10 General University Honors Galperina 1 Looking back at history, although art is not a necessity like water or food, it has always been an integral part in the development of all civilizations. So what part does it play in society and what is its impact on people? One way to look at art is to look at what guides its development and what are the results that follow. In the case of this paper, I am focusing specifically on how the arts are shaped by the political bodies that govern people, specifically focusing on Communist regimes. This is art of public nature and an integral part of all society, because it is created with the purpose of being seen by many. This of course is not something unique to the Communist regimes, or even their time period. Art has had public function throughout history, all one has to do is look at something like the Renaissance altar pieces, the drawings and carvings on the walls of Egyptian monuments or the murals commissioned in USA through the New Deal. In fact the idea of “art for art’s sake” only developed in the early 19 th century. This means that historically art has been used for a particular function, or to convey a specific idea to the viewers. This does not mean that before the 19 th century art was always done for some grand purpose, private commissions existed too of course; but artists mostly relied on patrons and the art that was available to the public was often commissioned for a purpose, and usually conveyed some sort of message. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 233 3rd International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2018) The Combination of Literal Language and Visual Language When Poetry Meets Design* Tingjin Shi Xiamen University Tan Kah Kee College Xiamen, China Abstract—As a graphic designer, the author deeply explores history of world literature, attracting scholars from different the spiritual connotation of ancient poetry and gives new regions and ages to study. The author tries to transcend inspiration to poster design. The expression of images to ancient language barriers and interpret the important life experience poems can often carry more information and a modern meaning. in poetry through images. At the same time, the author also Literal language starts from visual language and then turns back expresses the understanding and imagination of all the things to it, which makes ancient poetry and modern design connect in universe. Therefore, images have become an important with each other, poets and designers get to know each other. The footnote of poetry. It can also be said that image is a spatial author's cross-boundary research reminds us that when we symbol or carrier of ancient poetry creation and modern art carry out research on the relationship between literal language design. and visual language, we should combine theory with creative practice to avoid empty talk and rhetorical criticism, seek logic Ancient poetry is a literary genre that uses written in the dialogue between watching and creating and give play to language to narrate, having a rich emotion and imagination. their aesthetic and social value in the contemporary context. -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fashioning the Reclusive Persona: Zeng Jing's Informal Portraits of the Jiangnan Literati Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2mx8m4wt Author Choi, Seokwon Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Fashioning the Reclusive Persona: Zeng Jing’s Informal Portraits of the Jiangnan Literati A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Art History by Seokwon Choi Committee in charge: Professor Peter C. Sturman, Chair Professor Miriam Wattles Professor Hui-shu Lee December 2016 The dissertation of Seokwon Choi is approved. _____________________________________________ Miriam Wattles _____________________________________________ Hui-shu Lee _____________________________________________ Peter C. Sturman, Committee Chair September 2016 Fashioning the Reclusive Persona: Zeng Jing’s Informal Portraits of the Jiangnan Literati Copyright © 2016 by Seokwon Choi iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincerest gratitude goes to my advisor, Professor Peter C. Sturman, whose guidance, patience, and confidence in me have made my doctoral journey not only possible but also enjoyable. It is thanks to him that I was able to transcend the difficulties of academic work and find pleasure in reading, writing, painting, and calligraphy. As a role model, Professor Sturman taught me how to be an artful recluse like the Jiangnan literati. I am also greatly appreciative for the encouragement and counsel of Professor Hui-shu Lee. Without her valuable suggestions from its earliest stage, this project would never have taken shape. I would like to express appreciation to Professor Miriam Wattles for insightful comments and thought-provoking discussions that helped me to consider the issues of portraiture in a broader East Asian context. -

Painting Outside the Lines: How Daoism Shaped

PAINTING OUTSIDE THE LINES: HOW DAOISM SHAPED CONCEPTIONS OF ARTISTIC EXCELLENCE IN MEDIEVAL CHINA, 800–1200 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGION (ASIAN) AUGUST 2012 By Aaron Reich Thesis Committee: Poul Andersen, Chairperson James Frankel Kate Lingley Acknowledgements Though the work on this thesis was largely carried out between 2010–2012, my interest in the religious aspects of Chinese painting began several years prior. In the fall of 2007, my mentor Professor Poul Andersen introduced me to his research into the inspirational relationship between Daoist ritual and religious painting in the case of Wu Daozi, the most esteemed Tang dynasty painter of religious art. Taken by a newfound fascination with this topic, I began to explore the pioneering translations of Chinese painting texts for a graduate seminar on ritual theory, and in them I found a world of potential material ripe for analysis within the framework of religious studies. I devoted the following two years to intensive Chinese language study in Taiwan, where I had the fortuitous opportunity to make frequent visits to view the paintings on exhibit at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. Once I had acquired the ability to work through primary sources, I returned to Honolulu to continue my study of literary Chinese and begin my exploration into the texts that ultimately led to the central discoveries within this thesis. This work would not have been possible without the sincere care and unwavering support of the many individuals who helped me bring it to fruition.